The Perils of Identifying As Indigenous on Social Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Letter to the Editor

Women’sStudicsInt. Forum, Vol. 14. No. 2, pp. 505-513, 1991 0277-5395/91 13.00 + .OO Printed in the USA. 0 1991 Pergamon Flrss plc LETTERS To THE EDITORS Editorial Since its inception in 1978, WSIF has been was her second language. This culminated in very concerned about systemic male violence a paper given by Anna Yeatman at the Na- against women which knows neither class, tional Women’s Studies Conference in Mel- race nor cultural boundaries and in that time bourne, October 1990, which rendered Topsy we have published many articles on this top- Napurrula Nelson invisible and further im- ic. We therefore welcomed Diane Bell’s and pugned Diane Bell’s work. Meanwhile, male Topsy Napurrula Nelson’s important article violence against Aboriginal women contin- on intra-racial violence against women in ues. Australia: “Speaking about rape is everyone’s What follows is the correspondence WSIF business” (WSIF2(4), 1989). Reactions to received by Jackie Huggins et al., Topsy Na- the article were many, mainly positive: grate- purrula Nelson and Diane Bell. Contrary to ful for the authors’ courage to discuss a ta- rumours circulating in Australia, we never re- boo subject. A group of Australian Abori- fused to publish the letter by the Aboriginal ginal women, however, took issue with Bell’s women. But we felt that the debate deserved and Napurrula Nelson’s article: not with the more than an unsigned letter with typed reality of rape- this fact, as with rape of names, and no return address( Robyn women globally, remains uncontested-but Rowland wrote twice asking for a more de- with the question of authorship. -

Writing Cultures 11/11

.. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts Board, Australia Council PO Box 788 Strawberry Hills NSW 2012 Tel: (02) 9215 9065 Toll Free: 1800 226 912 Fax: (02) 9215 9061 Email: [email protected] www.ozco.gov.au cultures . WRITING ..... Protocols for Producing Indigenous Australian Literature An initiative of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait ISBN: 0 642 47240 8 Islander Arts Board of the Australia Council Writing Cultures: Protocols for Producing Indigenous Australian Literature Recognition and protection 18 contents Resources 18 Introduction 1 Copyright 20 Using the Writing Cultures guide 2 What is copyright? 20 What are protocols? 3 How does copyright protect literature? 20 What is Indigenous literature? 3 Who owns copyright? 20 Special nature of Indigenous literature 4 What rights do copyright owners have? 21 Collaborative works 21 Indigenous heritage 5 Communal ownership vs. joint ownership 21 Current protection of heritage 6 How long does copyright last? 22 Principles and protocols 8 What is the public domain? 22 Respect 8 What are moral rights? 22 Acknowledgement of country 8 Licensing for publication 22 Representation 8 Assigning copyright 23 Accepting diversity 8 Publishing contracts 23 Living cultures 9 Managing copyright to protect your interests 23 Indigenous control 9 Copyright notice 23 Commissioning Indigenous writers 9 Moral rights notice 24 Communication, consultation and consent 10 When is copyright infringed? 24 Creation stories 11 Fair dealings provisions 24 © Commonwealth of Australia 2002 Recording oral stories 11 -

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

Recreating the Circle: Reconstructing Indigenous Womanhood

CHAPTER 2 RECREATING THE CIRCLE: RECONSTRUCTING INDIGENOUS WOMANHOOD We can talk about self-government, sovereignty, cultural recovery and the heal- ing path, but we will never achieve any of these things until we take a serious look at the disrespect that characterizes the lives of so many Native women. Kim Anderson, A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood (14) Closely connected to the ways in which Indigenous feminism is presented in Paula Gunn Allen’s The Sacred Hoop, Lee Maracle’s I Am Woman, and Jackie Huggins’ Sister Girl is the recurring theme of how Indigenous women themselves are de- picted in these texts. This theme unfolds on two levels. There is the personal level, where Allen, Maracle and Huggins present their individual experiences of what it means to be an Indigenous woman in North America and Australia in the second half of the twentieth century. Then, on a larger scale, all three writers also examine the mechanisms of representing Indigenous womanhood, motherhood, and sisterhood that were developed and maintained by the mainstream American, Canadian and Australian settler cultures. In addition, they draw attention to the roles that mothers, grandmothers, sisters, aunts and female ancestors in general play in extended families, tribal communities and kinship structures as well as in reconstructing a positive and functioning sense of femininity. As was suggested in the previous chapter, womanhood and motherhood become an important site of difference for Indigenous women. The governing principles of Indigenous wom- en’s personal non-fiction and life writing in general include, on the one hand, grief over the loss of tribal powers, forcibly separated children, and the denial of motherhood, all resulting in the break-up of traditional family and tribal struc- tures, and on the other hand, the affirmation of female nurturing, maternity and sexuality, including the celebration of female ancestors. -

The Premiere Fund Slate for MIFF 2021 Comprises the Following

The MIFF Premiere Fund provides minority co-financing to new Australian quality narrative-drama and documentary feature films that then premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF). Seeking out Stories That Need Telling, the the Premiere Fund deepens MIFF’s relationship with filmmaking talent and builds a pipeline of quality Australian content for MIFF. Launched at MIFF 2007, the Premiere Fund has committed to more than 70 projects. Under the charge of MIFF Chair Claire Dobbin, the Premiere Fund Executive Producer is Mark Woods, former CEO of Screen Ireland and Ausfilm and Showtime Australia Head of Content Investment & International Acquisitions. Woods has co-invested in and Executive Produced many quality films, including Rabbit Proof Fence, Japanese Story, Somersault, Breakfast on Pluto, Cannes Palme d’Or winner Wind that Shakes the Barley, and Oscar-winning Six Shooter. ➢ The Premiere Fund slate for MIFF 2021 comprises the following: • ABLAZE: A meditation on family, culture and memory, indigenous Melbourne opera singer Tiriki Onus investigates whether a 70- year old silent film was in fact made by his grandfather – civil rights leader Bill Onus. From director Alex Morgan (Hunt Angels) and producer Tom Zubrycki (Exile in Sarajevo). (Distributor: Umbrella) • ANONYMOUS CLUB: An intimate – often first-person – exploration of the successful, yet shy and introverted, 33-year-old queer Australian musician Courtney Barnett. From producers Pip Campey (Bastardy), Samantha Dinning (No Time For Quiet) & director Danny Cohen. (Dist: Film Art Media) • CHEF ANTONIO’S RECIPES FOR REVOLUTION: Continuing their series of food-related social-issue feature documentaries, director Trevor Graham (Make Hummus Not War) and producer Lisa Wang (Monsieur Mayonnaise) find a very inclusive Italian restaurant/hotel run predominately by young disabled people. -

Visionsplendidfilmfest.Com

Australia’s only outback film festival visionsplendidfilmfest.comFor more information visit visionsplendidfilmfest.com Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival 2017 WELCOME TO OUTBACK HOLLYWOOD Welcome to Winton’s fourth annual Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival. This year we honour and celebrate Women in Film. The program includes the latest in Australian contemporary, award winning, classic and cult films inspired by the Australian outback. I invite you to join me at this very special Australian Film Festival as we experience films under the stars each evening in the Royal Open Air Theatre and by day at the Winton Shire Hall. Festival Patron, Actor, Mr Roy Billing OAM MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR TOURISM AND MAJOR EVENTS THE HON KATE JONES MP It is my great pleasure to welcome you to Winton’s Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival, one of Queensland’s many great event experiences here in outback Queensland. Events like the Vision Splendid Outback Film Festival are vital to Queensland’s tourism prosperity, engaging visitors with the locals and the community, and creating memorable experiences. The Palaszczuk Government is proud to support this event through Tourism and Events Queensland’s Destination Events Program, which helps drive visitors to the destination, increase expenditure, support jobs and foster community pride. There is a story to tell in every Queensland event and I hope these stories help inspire you to experience more of what this great State has to offer. Congratulations to the event organisers and all those involved in delivering the outback film festival and I encourage you to take some time to explore the diverse visitor experiences in Outback Queensland. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation Policies on Asian Immigration and Multiculturalism

Still Anti-Asian? Anti-Chinese? One Nation policies on Asian immigration and multiculturalism 仍然反亚裔?反华裔? 一国党针对亚裔移民和多元文化 的政策 Is Pauline Hanson’s One Nation party anti-Asian? Just how much has One Nation changed since Pauline Hanson first sat in the Australian Parliament two decades ago? This report reviews One Nation’s statements of the 1990s and the current policies of the party. It concludes that One Nation’s broad policies on immigration and multiculturalism remain essentially unchanged. Anti-Asian sentiments remain at One Nation’s core. Continuity in One Nation policy is reinforced by the party’s connections with anti-Asian immigration campaigners from the extreme right of Australian politics. Anti-Chinese thinking is a persistent sub-text in One Nation’s thinking and policy positions. The possibility that One Nation will in the future turn its attacks on Australia's Chinese communities cannot be dismissed. 宝林·韩森的一国党是否反亚裔?自从宝林·韩森二十年前首次当选澳大利亚 议会议员以来,一国党改变了多少? 本报告回顾了一国党在二十世纪九十年代的声明以及该党的现行政策。报告 得出的结论显示,一国党关于移民和多元文化的广泛政策基本保持不变。反 亚裔情绪仍然居于一国党的核心。通过与来自澳大利亚极右翼政坛的反亚裔 移民竞选人的联系,一国党的政策连续性得以加强。反华裔思想是一国党思 想和政策立场的一个持久不变的潜台词。无法排除一国党未来攻击澳大利亚 华人社区的可能性。 Report Philip Dorling May 2017 ABOUT THE AUSTRALIA INSTITUTE The Australia Institute is an independent public policy think tank based in Canberra. It is funded by donations from philanthropic trusts and individuals and commissioned research. Since its launch in 1994, the Institute has carried out highly influential research on a broad range of economic, social and environmental issues. OUR PHILOSOPHY As we begin the 21st century, new dilemmas confront our society and our planet. Unprecedented levels of consumption co-exist with extreme poverty. Through new technology we are more connected than we have ever been, yet civic engagement is declining. -

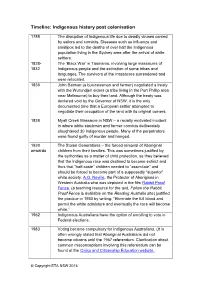

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

A Sociology of the Chick Lit of Anita Heiss

A Sociology of the Chick Lit of Anita Heiss By Fiannuala Morgan Submitted in total fulfillment of the requirements of Master of Arts (Thesis only) School of Culture and Communication, University of Melbourne 1 Abstract Wiradjuri woman, Anita Heiss, is arguably one of the first Australian authors of popular fiction. Since 2007, she has published across a diversity of genres including chick lit, contemporary women’s fiction, romance, memoir and children’s literature. A focus on the political characterises her work; and her identity as an author is both supplemented and complemented by her roles as an academic, activist and public intellectual. Heiss has discussed genre as a means of targeting specific audiences that may be less engaged with Indigenous affairs, and positions her novels as educative but not didactic. There remains, however, some ambivalence about the significance of the role that genre plays in her literature as well as for the diverse and differentiated audience that she attracts. The aims of this thesis then are two-fold: firstly, to present a complication of academic conceptions of genre, then to use this discussion to explore the social significance of Heiss’ literature. My focus is Heiss’ first four chick lit novels: Not Meeting Mr Right (2007), Avoiding Mr Right (2008), Manhattan Dreaming (2010) and Paris Dreaming (2011). Scholarship in the field leans toward an understanding that the racial politics of non-white articulations of the chick lit genre are invariably incompatible with the basic formula of chick lit texts. My thesis proposes a methodological shift from the dominant mode of ideological analysis to one that is largely focused on reader response. -

DNA Nation Press

PRESS KIT DISTRIBUTOR CONTACT PRODUCTION CONTACT SBS International Blackfella Films Lara von Ahlefeldt Darren Dale Tel: +61 2 9430 3240 Tel: +61 2 9380 4000 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 10 Cecil Street Paddington NSW 2021 Tel: +612 9380 4000 Fax: +612 9252 9577 Email: [email protected] www.blackfellafilms.com.au Production Notes Producer Darren Dale Producer & Writer Jacob Hickey Series Producer Bernice Toni Director Bruce Permezel Production Company Blackfella Films Genre Documentary Series Language English Aspect Ratio 16:9 FHA Duration EP 1 00:51:53:00 EP 2 00:54:54:00 EP 3 00:52:58:00 Sound Stereo Shooting Gauges Arri Amira, F55, DJI Inspire Drone, Blackmagic & Go Pro Logline Who are we? And where do we come from? Short Synopsis Who are we? And where do we come from? Australia’s greatest Olympian Ian Thorpe, iconic Indigenous actor Ernie Dingo, and TV presenter and Queen of Eurovision Julia Zemiro set off on an epic journey of genetic time travel to find out. © 2016 Blackfella Films Pty Ltd Page 2 of 40 Long Synopsis Who are we? And where do we come from? Australia’s greatest Olympian Ian Thorpe, iconic Indigenous actor Ernie Dingo, and TV presenter and Queen of Eurovision Julia Zemiro set off on an epic journey of genetic time travel to find out. DNA is the instruction manual that helps build and run our bodies. But scientific breakthroughs have discovered another remarkable use for it. DNA contains a series of genetic route maps. It means we can trace our mother’s mother’s mother and our father’s father’s father, and so on, back through tens of millennia, revealing how our ancestors migrated out of Africa and went on to populate the rest of the world.