1 Bibliography for Ancestral Modern: Australian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

The Art of Philip Wolfhagen a Newcastle Art Gallery and Tasmanian NEWCASTLE ART GALLERY, NSW Museum and Art Gallery Travelling Exhibition

Photographer: Tristan Sharp Philip Wolfhagen studio in Tasmania (2012) ABOUT THESE PAGES FOR EXHIBITION DATES PLEASE SEE THE TOUR SCHEDULE BELOW. This webpage supports the exhibition, Illumination The art of Philip Wolfhagen A Newcastle Art Gallery and Tasmanian NEWCASTLE ART GALLERY, NSW Museum and Art Gallery travelling exhibition. 22 June - 11 August 2013 Designed in conjunction with the Illumination The art of TASMANIAN MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY, TAS Philip Wolfhagen Education kit, this webpage provides 13 September - 1 December 2013 insight into the materials, artists, music and places that are important to Wolfhagen, and is recommended as an ad- THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY DRILL HALL GAL- ditional resource for teachers and students or for general LERY, ACT public use. 20 February - 6 April 2014 Surveying the twenty five year career of Australian painter CAIRNS REGIONAL GALLERY, QLD Philip Wolfhagen, Illumination The art of Philip Wolfhagen 9 May - 6 July 2014 explores the artist’s enchantment with the Australian land- scape, the tactility and intimacy of his painting process, his TWEED RIVER ART GALLERY, NSW command of colour and use of signature devices such as 8 August - 12 October 2014 the split picture plane. HAMILTON ART GALLERY, VIC Wolfhagen’s work is held in major public and corporate 15 November 2014 - 1 February 2015 collections in Australia and in private collections nationally and internationally, with the largest national public col- GIPPSLAND ART GALLERY, VIC lection of his work currently owned by the Newcastle Art 14 February - 12 April 2015 Gallery. Newcastle Art Gallery strongly supports experience-based learning and advises that this webpage be used in conjunc- tion with a visit to the exhibition. -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

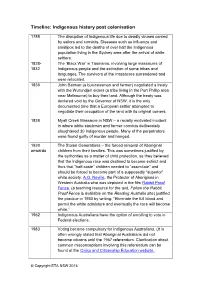

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Mr R Peters 1934 - 2020, Springvale Station, Turkey Creek, WA

Mr R Peters 1934 - 2020, Springvale Station, Turkey Creek, WA BIOGRAPHY: Rusty Peters is a senior Gija man of Juwurru skin. His bush name Dirjji refers to dingo pups looking out of a hole at the sunrise. He was born under a Warlagarri or Supplejack tree on Springvale Station south west of Turkey Creek the same day as his jimarri or age mate Charlie McAdam. His spirit came from a crocodile his father had killed when his mother became pregnant. He grew up on Springvale learning traditional law and working as a stockman and at other things such as welding fences and stock yards. When his father was killed in a tragic riding accident at Roses Yard, the family moved to Mabel Downs where he became renowned as a horse breaker. He lived for some time at Nine Mile reserve at Wyndham after the introduction of award wages forced people off stations but then moved to Turkey Creek where with other senior Gija artists such as Hector Jandany and George Mung-Mung he helped start the school. In 1989 he moved to Kununurra where he was employed at Waringarri Aboriginal Arts as an assistant. He was a long time friend of Rover Thomas, caring for him on most of the trips he made in the later part of his life. He made prints and did some painting while working for Waringarri Arts. He moved to Crocodile Hole when Freddie Timms based the Jirrawun Aboriginal Arts group there in 1997 and began to paint on large canvases. His detailed knowledge of the land and stories from Springvale and neighbouring Moolabulla stations is reflected in distinctive paintings in traditional red and yellow ochres and black charcoal. -

Ngarranggarni Gija Two-Way Learning and the University of Melbourne Gabriel Nodea and Robyn Sloggett

ngarranggarni Gija Two-Way Learning and the University of Melbourne Gabriel Nodea and Robyn Sloggett Introduction knowledge and are responsible for many of the cattle stations, in the Warmun is a small township owned keeping it strong, and for teaching it early 1970s Warmun became a refugee and managed by Gija people in the to future generations. This knowledge camp. People were physically removed east Kimberley region of Western cannot be passed on without the from their country, so that simple acts Australia. Situated between Kununurra permission of the Old People. like finding food and water, as well as and Hall’s Creek, Warmun is also On one level, this article is about complex activities like ceremony and located on the ancient Wirnan an educational partnership between caring for country, could no longer be (sharing and trading) exchange the Grimwade Centre for Cultural carried out. This made Gija people route that stretched inland from the Materials Conservation at the feel disempowered and sad. They coastline around Derby to the west, to University of Melbourne and the felt as if they had been pushed aside that around Wadeye to the north-east. Warmun Art Centre, but it is also from the country they had looked Trade and shared knowledge have about the contemporary influence after through all time, and that they always been an important part of the of Ngarranggarni, which has become could no longer make decisions about social, cultural and spiritual fabric of an important part of the education caring for country. It brought down Gija life, and it was along this route programs at the Grimwade Centre, their spirits and made them feel that Gija people—working through and is now extending beyond like they were losing their strength. -

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Marie Geissler All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5546-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5546-4 Front Cover: John Mawurndjul (Kuninjku people) Born 1952, Kubukkan near Marrkolidjban, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory Namanjwarre, saltwater crocodile 1988 Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta) 206.0 x 85.0 cm (irreg) Collection Art Gallery of South Australia Maude Vizard-Wholohan Art Prize Purchase Award 1988 Accession number 8812P94 © John Mawurndjul/Copyright Agency 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Prologue ..................................................................................................... ix Theorizing contemporary Indigenous art - post 1990 Overview ................................................................................................ -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

Module Details

Paper: 07; Module No: 04: E Text (A) Personal Details: Role Name Affiliation Principal Investigator: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Paper Coordinator: Prof. Suchorita Chattopadhyay Jadavpur University Coordinator for This Module: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Content Writer: Mr. Ayan Ghosh CIIL, Mysore Content Reviewer: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad Language Editor: Prof. Tutun Mukherjee University of Hyderabad (B) Description of Module: Items Description of Module Subject Name: English Paper No & Name: 07; Canadian, Australian and South Pacific Literatures in English Module No & Title: 04; Aboriginal Australia: History and Literature Pre-requisites: Basic knowledge of English Objectives: To provide an idea of Australian Aboriginal History and Literature Key Words: Australian Aboriginal History, Australian Aboriginal Literature, Australian Literature 1 Contents I. What is Aboriginality? II. Brief history of Aborigines III. Introduction to Indigenous Culture IV. Introduction to Aboriginal Art V. Aboriginal Music VI. Aboriginal Paintings VII. Papunya Tula or Papunya Art VIII. Aboriginal Literature IX. What is dream Time? X. Dreamtime and Indigenous Literature XI. Aboriginal Literature and its position XII. Famous Literary personnel XIII. Glimpses of Aboriginal Films XIV. Conclusion About the Module: In this module we are going to learn that what the Aborigine actually means, from where this term came from and for whom it is being used. In addition to this we are going to learn about Aboriginal History, about their land in a brief manner. We will discuss some of their art form and will try to get acquainted with their culture in the first half of this module. In the second part, we will learn that what the ‘Dreamtime’ actually is and how is it related with their literature. -

Lauraine Diggins Fine

5 Malakoff Street, North Caulfield, Vic, 3161 Telephone: (61 3) 9509 9855 Facsimile: (61 3) 9509 4549 Email: [email protected] Website: www.diggins.com.au ABN.19006 457 101 L A U R A I N E · D I G G I N S · F I N E · A R T Memorial Service to celebrate the life of Lauraine Diggins OAM Monday 17th June 2019, The Pavilion, Arts Centre Melbourne TRIBUTES MC: Ruth Lovell, manager, Lauraine Diggins Fine Art Acknowledgement of Country: Professor Margo Neale, Senior Curator and Principal Indigenous Advisor, National Museum of Australia Speakers: Ms Lin Oke, O.T. Group Dr Daniel Thomas, Emeritus Director Art Gallery of South Australia Ms Antonia Syme, Director, Australian Tapestry Workshop Mr Adrian Newstead, Founding Director, Cooee Art Mr Steve Dimopoulos MP, Member for Oakleigh Mr Gerard Vaughan, former Director National Gallery of Australia Ms Anne-Marie Schwirtlich, former Director National Library of Australia (delivered by Nerida Blanche, daughter of Lauraine Diggins) Mr Michael Blanche, husband of Lauraine Diggins Tribute to Lauraine Diggins by Ms Lin Oke Reflections Occupational Therapy Back in 1965, 42 of us 17 and 18 year olds, from around Victoria started our journey into the Occupational therapy profession. Strong bonds of friendship developed amongst us. Lauraine stood out – vivacious, full of fun, elegant, tall – with those long legs that resulted in some of us calling her Lolly Legs. Following Lauraine’s passing we shared our memories and smiled on our reflections. I’m pleased to share some of these reflections with you today. One of our group summed up the closeness of Course 18 in this way: “In 1965 the small campus of the OT School at 33 Lansell Road provided an intimate atmosphere favourable for the development of strong bonds. -

Ethnographic Film-Making in Australia: the First Seventy Years

ETHNOGRAPHIC FILM-MAKING IN AUSTRALIA THE FIRST SEVENTY YEARS (1898-1968) Ian Dunlop Ethnographic film-making is almost as old as cinema itself.1 In 187 7 Edison, in America, perfected his phonograph, the world’s first machine for recording sound — on fragile wax cylinders. He then started experimenting with ways of producing moving pictures. Others in England and France were also experimenting at the same time. Amongst these were the Lumiere brothers of Paris. In 1895 they perfected a projection machine and gave the world’s first public screening. The cinema was born. The same year Felix-Louis Renault filmed a Wolof woman from west Africa making pots at the Exposition Ethnographique de l’Afrique Occidentale in Paris.2 Three years later ethnographic film was being shot in the Torres Strait Islands just north of mainland Australia. This was in 1898 when Alfred Cort Haddon, an English zoologist and anthro pologist, mounted his Cambridge Anthropological Expedition to the Torres Strait. His recording equipment included a wax cylinder sound recorder and a Lumiere camera. The technical genius of the expedition, and the man who apparently used the camera, was Anthony Wilkin.3 It is not known how much film he shot; unfortunately only about four minutes of it still exists. It is the first known ethnographic film to be shot in the field anywhere in the world. It is of course black and white, shot on one of the world’s first cameras, with a handle you had to turn to make the film go rather shakily around. The fragment we have shows several rather posed shots of men dancing and another of men attempting to make fire by friction.