What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

The Art of Philip Wolfhagen a Newcastle Art Gallery and Tasmanian NEWCASTLE ART GALLERY, NSW Museum and Art Gallery Travelling Exhibition

Photographer: Tristan Sharp Philip Wolfhagen studio in Tasmania (2012) ABOUT THESE PAGES FOR EXHIBITION DATES PLEASE SEE THE TOUR SCHEDULE BELOW. This webpage supports the exhibition, Illumination The art of Philip Wolfhagen A Newcastle Art Gallery and Tasmanian NEWCASTLE ART GALLERY, NSW Museum and Art Gallery travelling exhibition. 22 June - 11 August 2013 Designed in conjunction with the Illumination The art of TASMANIAN MUSEUM AND ART GALLERY, TAS Philip Wolfhagen Education kit, this webpage provides 13 September - 1 December 2013 insight into the materials, artists, music and places that are important to Wolfhagen, and is recommended as an ad- THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY DRILL HALL GAL- ditional resource for teachers and students or for general LERY, ACT public use. 20 February - 6 April 2014 Surveying the twenty five year career of Australian painter CAIRNS REGIONAL GALLERY, QLD Philip Wolfhagen, Illumination The art of Philip Wolfhagen 9 May - 6 July 2014 explores the artist’s enchantment with the Australian land- scape, the tactility and intimacy of his painting process, his TWEED RIVER ART GALLERY, NSW command of colour and use of signature devices such as 8 August - 12 October 2014 the split picture plane. HAMILTON ART GALLERY, VIC Wolfhagen’s work is held in major public and corporate 15 November 2014 - 1 February 2015 collections in Australia and in private collections nationally and internationally, with the largest national public col- GIPPSLAND ART GALLERY, VIC lection of his work currently owned by the Newcastle Art 14 February - 12 April 2015 Gallery. Newcastle Art Gallery strongly supports experience-based learning and advises that this webpage be used in conjunc- tion with a visit to the exhibition. -

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

The Aboriginal Version of Ken Done... Banal Aboriginal Identities in Australia

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: McKee, Alan (1997) The Aboriginal version of Ken Done ... banal aboriginal identities in Aus- tralia. Cultural Studies, 11(2), pp. 191-206. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/42045/ c Copyright 1997 Taylor & Francis This is an electronic version of an article published in [Cultural Studies, 11(2), pp. 191-206]. [Cultural Studies] is available online at informaworld. Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502389700490111 "The Aboriginal version of Ken Done..." Banal Aboriginality in Australia This writing explores the ways in which representations of blackness in Australia are quite specific to that country. Antipodean images of black Australians are limited in particular ways, influenced by traditions, and forming genealogies quite peculiar to that country. In particular, histories of blackness in Australia are quite different that in America. The generic alignments, the 'available discourses' on blackness (Muecke, 1982) form quite distinct topographies, masses and lacunae, distributed differently in the two continents. It is in these gaps, the differences between the countries — in the space between Sale of the Century in Australia and You Bet Your Life in the USA — that this article discusses the place of fatality in Australian images of the Aboriginal. -

AUSTRALIA MEDIA 8 June 2021

Up to date business Industry intelligence reports covering developments in the world’s SnapShots fastest growing industries N0.: 26801 Follow us on : AUSTRALIA MEDIA 8 June 2021 This Week’s News • Reuters – Australian financial crime watchdog widens probe on casinos already reeling from COVID – 7/6/2021 Australia’s anti-money-laundering agency on Monday widened a probe into due diligence at casinos to include the three biggest operators, ratcheting up pressure on a sector already Contents struggling with the pandemic and heightened regulatory scrutiny. For the complete story, see: https://www.reuters.com/business/australian-watchdog-widens-crown-casino-probe- • News and Commentary adds-nz-owned-skycity-2021-06-06/ • Media Releases • Argus Media – Australia’s Gladstone port diversifies May coal exports – 7/6/2021 Above-average coal shipments to Japan, India and South Korea from Australia’s port of • Latest Research Gladstone in Queensland, as well as diversification into new markets, partially offset a lack of • The Industry sales to China. For the complete story, see: https://www.argusmedia.com/en/news/2222125-australias-gladstone-port-diversifies- • Leading Companies in the Industry may-coal-exports • Reuters - Australian media fined $840,000 for gag order breach in Pell sex assault case – 4/6/2021 An Australian court on Friday ordered a dozen media firms to pay a total of A$1.1 million ($842,000) in fines for breaching a suppression order on reporting the conviction. For the complete story, see: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/australian-court-fines-media-breach-suppression- -

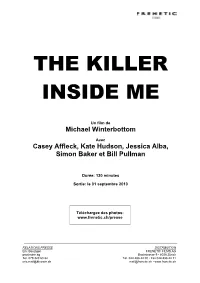

The Killer Inside Me

THE KILLER INSIDE ME Un film de Michael Winterbottom Avec Casey Affleck, Kate Hudson, Jessica Alba, Simon Baker et Bill Pullman Durée: 120 minutes Sortie: le 01 septembre 2010 Téléchargez des photos: www.frenetic.ch/presse RELATIONS PRESSE DISTRIBUTION Eric Bouzigon FRENETIC FILMS AG prochaine ag Bachstrasse 9 • 8038 Zürich Tél. 079 320 63 82 Tél. 044 488 44 00 • Fax 044 488 44 11 [email protected] [email protected] • www.frenetic.ch SYNOPSIS Based on the novel by legendary pulp writer Jim Thompson, Michael Winterbottom’s THE KILLER INSIDE ME tells the story of handsome, charming, unassuming small town sheriff’s deputy Lou Ford. Lou has a bunch of problems. Woman problems. Law enforcement problems. An ever-growing pile of murder victims in his west Texas jurisdiction. And the fact he’s a sadist, a psychopath, a killer. Suspicion begins to fall on Lou, and it’s only a matter of time before he runs out of alibis. But in Thompson’s savage, bleak, blacker than noir universe nothing is ever what it seems, and it turns out that the investigators pursuing him might have a secret of their own. CAST Lou Ford.........................................................................................................................................CASEY AFFLECK Joyce Lakeland ..................................................................................................................................JESSICA ALBA Amy Stanton..................................................................................................................................... -

Crash- Amundo

Stress Free - The Sentinel Sedation Dentistry George Blashford, DMD tvweek 35 Westminster Dr. Carlisle (717) 243-2372 www.blashforddentistry.com January 19 - 25, 2019 Don Cheadle and Andrew Crash- Rannells star in “Black Monday” amundo COVER STORY .................................................................................................................2 VIDEO RELEASES .............................................................................................................9 CROSSWORD ..................................................................................................................3 COOKING HIGHLIGHTS ....................................................................................................12 SPORTS.........................................................................................................................4 SUDOKU .....................................................................................................................13 FEATURE STORY ...............................................................................................................5 WORD SEARCH / CABLE GUIDE .........................................................................................19 READY FOR A LIFT? Facelift | Neck Lift | Brow Lift | Eyelid Lift | Fractional Skin Resurfacing PicoSure® Skin Treatments | Volumizers | Botox® Surgical and non-surgical options to achieve natural and desired results! Leo D. Farrell, M.D. Deborah M. Farrell, M.D. www.Since1853.com MODEL Fredricksen Outpatient Center, 630 -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

9 SONGS-B+W-TOR

9 SONGS AFILMBYMICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM One summer, two people, eight bands, 9 Songs. Featuring exclusive live footage of Black Rebel Motorcycle Club The Von Bondies Elbow Primal Scream The Dandy Warhols Super Furry Animals Franz Ferdinand Michael Nyman “9 Songs” takes place in London in the autumn of 2003. Lisa, an American student in London for a year, meets Matt at a Black Rebel Motorcycle Club concert in Brixton. They fall in love. Explicit and intimate, 9 SONGS follows the course of their intense, passionate, highly sexual affair, as they make love, talk, go to concerts. And then part forever, when Lisa leaves to return to America. CAST Margo STILLEY AS LISA Kieran O’BRIEN AS MATT CREW DIRECTOR Michael WINTERBOTTOM DP Marcel ZYSKIND SOUND Stuart WILSON EDITORS Mat WHITECROSS / Michael WINTERBOTTOM SOUND EDITOR Joakim SUNDSTROM PRODUCERS Andrew EATON / Michael WINTERBOTTOM EXECUTIVE PRODUCER Andrew EATON ASSOCIATE PRODUCER Melissa PARMENTER PRODUCTION REVOLUTION FILMS ABOUT THE PRODUCTION IDEAS AND INSPIRATION Michael Winterbottom was initially inspired by acclaimed and controversial French author Michel Houellebecq’s sexually explicit novel “Platform” – “It’s a great book, full of explicit sex, and again I was thinking, how come books can do this but film, which is far better disposed to it, can’t?” The film is told in flashback. Matt, who is fascinated by Antarctica, is visiting the white continent and recalling his love affair with Lisa. In voice-over, he compares being in Antarctica to being ‘two people in a bed - claustrophobia and agoraphobia in the same place’. Images of ice and the never-ending Antarctic landscape are effectively cut in to shots of the crowded concerts. -

Film at Lincoln Center New Releases Series & Festivals March 2020

Film at Lincoln Center March 2020 New Releases The Whistlers Bacurau The Truth The Traitor Series & Festivals Rendez-Vous with French Cinema Mapping Bacurau New Directors/ New Films Members save $5 Tickets: filmlinc.org Elinor Bunin Munroe Film Center 144 West 65th Street, New York, NY Walter Reade Theater 165 West 65th Street, New York, NY FESTIVAL Rendez-Vous with French Cinema MARCH 5–15 Co-presented with UniFrance, the 25th edition of Rendez-Vous demonstrates that the landscape of French cinema is as fertile, inspiring, and distinct as ever. Organized by Florence Almozini with UniFrance. ( In-Person Appearance) Special Student Savings! $50 All-Access Pass NEW YORK PREMIERE Deerskin Quentin Dupieux, France, 2019, 77m Oscar- winner Jean Dujardin and Adèle Haenel star in a rollicking take on the midlife crisis movie, directed by Rendez-Vous mainstay Quentin Dupieux. A Greenwich Entertainment release. Sunday, March 8, 9:15pm Saturday, March 14, 9:00pm NORTH AMERICAN PREMIERE An Easy Girl Rebecca Zlotowski, France, 2019, 92m Cuties Rebecca Zlotowski’s fourth feature taps into the universal hunger of adolescence, and OPENING NIGHT • NEW YORK PREMIERE U.S. PREMIERE imbues an empathetic coming-of-age story The Truth Burning Ghost with a sharp class critique. A Netflix release. Hirokazu Kore-eda, France/Japan, 2019, 106m Stéphane Batut, France, 2019, 104m Winner of Saturday, March 7, 9:00pm In his follow-up to the Palme d’Or–winning the prestigious Prix Jean Vigo, this smoldering Thursday, March 12, 4:00pm Shoplifters, Hirokazu Kore-eda casts two titans feature debut from Stéphane Batut is an of French cinema, Catherine Deneuve and entrancing tale of aching romanticism on the NEW YORK PREMIERE Juliette Binoche, in a film structured around the precipice of life and death. -

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art

The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler The Making of Indigenous Australian Contemporary Art: Arnhem Land Bark Painting, 1970-1990 By Marie Geissler This book first published 2020 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2020 by Marie Geissler All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-5546-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-5546-4 Front Cover: John Mawurndjul (Kuninjku people) Born 1952, Kubukkan near Marrkolidjban, Arnhem Land, Northern Territory Namanjwarre, saltwater crocodile 1988 Earth pigments on Stringybark (Eucalyptus tetrodonta) 206.0 x 85.0 cm (irreg) Collection Art Gallery of South Australia Maude Vizard-Wholohan Art Prize Purchase Award 1988 Accession number 8812P94 © John Mawurndjul/Copyright Agency 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements .................................................................................. vii Prologue ..................................................................................................... ix Theorizing contemporary Indigenous art - post 1990 Overview ................................................................................................ -

Attack Force Z Head Credits

Opening titles: Z Special Force was a secret operations unit of the Australian Armed Services in World War Two. It was made up of volunteers from all branches of the Allied Forces and came under the direct command of General Douglas Macarthur. Z Special carried out two hundred and eighty- four war time missions in the Pacific. The most publicised of these were the successful canoe raid on Singapore harbour from the 'Krait' and the subsequent Rimau raid in which all twenty- three participants were either killed in action or executed. The events depicted in this film are an honest and unflinching account of the type of operation carried out by our unit during the war. John L. Gardner (signature) President Z Special Force Association of New South Wales 10th January, 1945. Straits of Sembalang South West Pacific John McCallum Productions Central Motion Picture Corporation presents JOHN PHILLIP LAW Lieutenant J. A. Veitch Army of the Netherland East Indies MEL GIBSON Captain P. G. Kelly Australian Imperial Forces SAM NEILL Sergeant D. J. Costello D.C.M. Australian Imperial Forces CHRIS HAYWOOD Able Seaman A.D. Bird Royal Navy JOHN WATERS Sub Lieutenant E. P. King Royal New Zealand Navy ATTACK FORCE Z (with logo sword penetrating Z) also starring KOO CHUAN-HSIUNG Lin Chan-Lang SYLVIA CHAN Chien Hua O TI Shaw Hu Executive Producers John McCallum George F. Chang Screenplay Roger Marshall Director of Photography Lin Hun-Chung Editor David Stiven Music Eric Jupp Produced by Lee Robinson Directed by Tim Burstall.