Aboriginal Influence on Archaeological Practice, a Case Study from New South Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Founding of Aboriginal History and the Forming of Aboriginal History

The founding of Aboriginal History and the forming of Aboriginal history Bain Attwood Nearly 40 years ago an important historical project was launched at The Australian National University (ANU). It came to be called Aboriginal history. It was the name of both a periodical and a historiographical movement. In this article I seek to provide a comprehensive account of the founding of the former and to trace something of the formation of the latter.1 Aboriginal history first began to be formed in the closing months of 1975 when a small group of historically-minded white scholars at ANU agreed to found what they described as a journal of Aboriginal History. At that time, the term, let alone the concept of Aboriginal history, was a novel one. The planners of this academic journal seem to have been among the first to use the phrase in its discursive sense when they suggested that it ‘should serve as a publications outlet in the field of Aboriginal history’.2 Significantly, the term was adopted in the public realm at much the same time. The reports of the Committee of Inquiry on Museums and National Collections (the Pigott Report) and the Planning Committee on the Gallery of Aboriginal Australia, which were the outcome of an inquiry commissioned by the Whitlam Labor Government in order to articulate and give expression to a new Australian nationalism by championing a past that was indigenous to the Australian continent, both used the term.3 As 1 I wish to thank Niel Gunson, Bob Reece and James Urry for allowing me to view some of their personal -

Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology, Part VII. Aboriginal

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Robertson, Gail, 2011. Changing perspectives in Australian archaeology, part VII. Aboriginal use of backed artefacts at Lapstone Creek rock-shelter, New South Wales: an integrated residue and use-wear analysis. Technical Reports of the Australian Museum, Online 23(7): 83–101. doi:10.3853/j.1835-4211.23.2011.1572 ISSN 1835-4211 (online) Published online by the Australian Museum, Sydney nature culture discover Australian Museum science is freely accessible online at http://publications.australianmuseum.net.au 6 College Street, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology edited by Jim Specht and Robin Torrence photo by carl bento · 2009 Papers in Honour of Val Attenbrow Technical Reports of the Australian Museum, Online 23 (2011) ISSN 1835-4211 Changing Perspectives in Australian Archaeology edited by Jim Specht and Robin Torrence Specht & Torrence Preface ........................................................................ 1 I White Regional archaeology in Australia ............................... 3 II Sullivan, Hughes & Barham Abydos Plains—equivocal archaeology ........................ 7 III Irish Hidden in plain view ................................................ 31 IV Douglass & Holdaway Quantifying cortex proportions ................................ 45 V Frankel & Stern Stone artefact production and use ............................. 59 VI Hiscock Point production at Jimede 2 .................................... 73 VII Robertson Backed artefacts Lapstone -

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

Themes in the Archaeology of Holocene Australia

THIS IS THE ACCEPTED VERSION OF THIS PAPER The final publication details are: Ulm, S. 2013 ‘Complexity’ and the Australian continental narrative: Themes in the archaeology of Holocene Australia. Quaternary International 285:182-192. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.03.046 The final publication is available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1040618212002078 © 2013. This manuscript version is made available under the CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 license http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ ‘Complexity’ and the Australian continental narrative: Themes in the archaeology of Holocene Australia Sean Ulm Department of Anthropology, Archaeology and Sociology, School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University, PO Box 6811, Cairns, QLD 4870, Australia Email: [email protected] Telephone: +61 7 4042 1194 Facsimile: +61 7 4042 1290 Abstract Accounts of long-term cultural change in Australia have emphasised the late Holocene as the period when ‘complexity’ emerged amongst foragers in Australia, associated with increased economic productivity, reduced mobility, population growth, intensified social relations and cosmological elaboration. These reconfigurations have often been interpreted as the result of continent-wide trajectories which began in the mid-Holocene, often termed ‘intensification’. These approaches have been found wanting as they homogenise diverse records of human adaptation into a single account which inexorably leads to the ethnographic present. The archaeological record tells a rather different story with fluctuating occupational intensity and even regional abandonments featuring in well-documented archaeological records. Instead, variability documented in the ethnographic and archaeological records can be understood as a product of local adaptations reflecting the operation of historically situated systems of social organisation in diverse environmental settings. -

The Age of Australian Rock Art: a Review Michelle C

Short Reports The Age of Australian Rock Art: A Review Michelle C. Langley1 and Paul S.C. Taçon2 Abstract The growing corpus of ‘direct dates’ for rock art around the world has changed the way researchers understand rock art. ‘Direct dating’ refers to methods for obtaining chronometric ages through the dating of material directly associated with motifs, thus providing minimum, maximum or actual ages. Materials associated with rock art that may be directly dated include the original media (e.g. beeswax), organic binders found in pigment, or natural coatings (e.g. wasp nests) which can either provide a terminus ante quem or terminus post quem for art. In Australia, 432 direct dates for rock art are now available, providing the basis for developing absolute chronologies for rock art regions and specific periods within them. In this paper we review the dating results but caution against using them to derive broad interpretations, especially continent-wide narratives and global comparisons. Figure 1 Location of sites included in this analysis. Note that Native Animals (NSW) and Pete’s Chase (QLD) are not shown as location Introduction information is not available. Only five reviews of the direct dating of Australian rock art have been undertaken. Bednarik (2002) presented a critical review north and south of 18ºS respectively. Ages were not calibrated of the processes for dating rock art but did not examine the where sample materials were not reported. For the purposes of direct dating of rock art in Australia in detail. David et al. (1999) examination, ages disputed by either the initial investigators or reviewed absolute dates for rock art in southeast Cape York subsequent commentators were not considered in the analyses Peninsula, while McDonald (2000) reviewed AMS determinations below, though they are included in the regional statistics and along with methodological issues for sites in the Sydney Basin. -

NAIDOC Week 2021

TEACHER GUIDE YEARS F TO 10 NAIDOC Week 2021 Warning – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander teachers and students are advised that this curriculumresource may contain images, voices or names of deceased people. Glossary Terms that may need to be introduced to students prior to teaching the resource: ceded: to hand over or give up something, such as land, to someone else. First Nations people: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. NAIDOC: (acronym) National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee. NAIDOC Week: a nationally recognised week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. All Australians are invited to participate. sovereignty: supreme authority and independent power claimed or possessed by a community or state to govern itself or another state. Resource overview Introduction to NAIDOC Week – A history of protest and celebration NAIDOC Week is usually celebrated in the first full week of July. It’s a week to celebrate the histories, cultures and achievements of First Nations people. Although NAIDOC Week falls in the mid-year school holidays, the aim of each theme isn’t limited to those set dates. Schools are encouraged to recognise and celebrate NAIDOC Week at any time throughout the year to ensure this important event isn’t overlooked. Themes can be incorporated as part of school life and the school curriculum. NAIDOC stands for ‘National Aborigines and Islanders Day Observance Committee’, the committee responsible for organising national activities during NAIDOC Week. Its acronym has now become the name of the week. NAIDOC Week has a long history beginning with the human rights movement for First Nations Peoples in the 1920s. -

The Archaeological Heritage of Christianity in Northern Cape York Peninsula

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University The Archaeological Heritage of Christianity in Northern Cape York Peninsula Susan McIntyre-Tamwoy Abstract For those who have worked in northern Cape York Peninsula and the Torres Strait, the term ‘coming of the light’ will have instant meaning as the symbolic reference to the advent of Christianity amongst Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This paper explores the approaches that anthropologists and archaeologist have adopted in exploring the issues around Christianity, Aboriginal people, missions and cultural transformations. For the most part these disciplines have pursued divergent interests and methodologies which I would suggest have resulted in limited understandings of the nature and form of contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander identity and a lack of appreciation of the material culture that evidences this transformation. Through an overview of some of the work undertaken in the region the paper explores the question ‘Can we really understand contemporary identity and the processes that have led to its development without fully understanding the complex connections between place and people and historical events and symbolic meaning, in fact the ‘social landscape of Aboriginal and Islander Christianity.’ This paper was presented in an earlier form at the Australian Anthropological Society 2003 Annual Conference held in Sydney. KEYWORDS: Archaeology, Christian Missions, Cape York Peninsula Introduction dominated profession, are squeamish about the impact of western religions on indigenous culture. In this paper I consider the overlap between • Thirdly, given that historical archaeology in Australia anthropological enquiry and archaeology in relation to has been heavily reliant on the investigation of built the Christian Mission period in the history of Cape York structures (Paterson & Wilson 2000:85) the nature of Peninsula. -

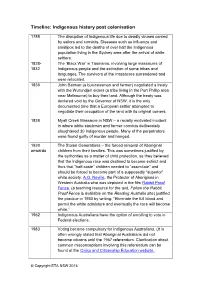

Indigenous History Post Colonisation

Timeline: Indigenous history post colonisation 1788 The disruption of Indigenous life due to deadly viruses carried by sailors and convicts. Diseases such as influenza and smallpox led to the deaths of over half the Indigenous population living in the Sydney area after the arrival of white settlers. 1828- The ‘Black War’ in Tasmania, involving large massacres of 1832 Indigenous people and the extinction of some tribes and languages. The survivors of the massacres surrendered and were relocated. 1835 John Batman (a businessman and farmer) negotiated a treaty with the Wurundjeri elders (a tribe living in the Port Phillip area near Melbourne) to buy their land. Although the treaty was declared void by the Governor of NSW, it is the only documented time that a European settler attempted to negotiate their occupation of the land with its original owners. 1838 Myall Creek Massacre in NSW – a racially motivated incident in where white stockmen and former convicts deliberately slaughtered 30 Indigenous people. Many of the perpetrators were found guilty of murder and hanged. 1930 The Stolen Generations – the forced removal of Aboriginal onwards children from their families. This was sometimes justified by the authorities as a matter of child protection, as they believed that the Indigenous race was destined to become extinct and thus that “half-caste” children needed to “assimilate” and should be forced to become part of a supposedly “superior” white society. A.O. Neville, the Protector of Aborigines in Western Australia who was depicted in the film Rabbit Proof Fence, (a teaching resource for the text, Follow the Rabbit Proof Fence is available on the Reading Australia site) justified the practice in 1930 by writing: “Eliminate the full blood and permit the white admixture and eventually the race will become white.” 1962 Indigenous Australians have the option of enrolling to vote in Federal elections. -

Australian Archaeology

Australian Archaeology Archived at Flinders University: dspace.flinders.edu.au Full Citation Details: Momood, M. 1978. Ken's Cave and the art of Central-Western Queensland. 'Australian Archaeology', no.8, 22-31. KEN'S CAVE AND THE ART OF CENTRAL-WESTERN QUEENSLAND M. Momood Abstract A date has been obtained for engraved art at a site in central- western Queensland. This may have more general implications for the art of the area. Ken's Cave is a rock-shelter located near the crest of the Great Divide, between the Barcoo and Belyando drainage systems, in central-western Queensland. It occurs at the base of a sandstone cliff of the Precipice Series, and from it a slope of large sandstone blocks descends to a forested sand flat. Here vegetation is predominantly of Black Wattle (Acacia cunninghamii) . Narrow-leaved iron-bark woodland (EucaZyptus drepmrophyZZa) is found beyond this on the steep slope down to undulating flats. These are dominated by communities of brigalow regrowth (A. hrpophyZZa) , brigalow-blackbutt forest (A. kpophyZZa-E. cumbagema), silver-leaved iron-bark woodland (E. meZanophZoia) , and poplar box grassy woodlands (E. popuznea) . The present property-owner knows of no water-source close to the site. The site measures 13 by 7 m, with a maximum height at the drip- line of 6 m. It faces due west (Fig.1). An occupation deposit is evident at the drip-line, where ash, charcoal, stone tools and bone have been exposed by erosion, and are slumping down a steep, poorly consolidated scarp of sand and talus. A grindstone was also found in situ. -

Another Snapshot for the Album: a Decade of Australian Archaeology in Profile Survey Data

ResearchOnline@JCU This is the Accepted Version of a paper published in the Journal Australian Archaeology: Mate, Geraldine, and Ulm, Sean (2016) Another snapshot for the album: a decade of Australian Archaeology in Profile survey data. Australian Archaeology, 82 (2). pp. 168-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03122417.2016.1213032 Another Snapshot for the Album: A Decade of Australian Archaeology in Profile Survey Data Geraldine Matea,b and Sean Ulmb a Cultures and Histories Program, Queensland Museum Network, South Brisbane, QLD, Australia b College of Arts, Society and Education, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD, Australia Abstract A comprehensive survey of Australian professional archaeologists undertaken in 2015 is used to explore key aspects and emerging trends in the state of the archaeological profession in Australia. Comparisons are made with data collected using the same survey instrument in 2005 and 2010 to allow consideration of longer-term disciplinary trends related to working conditions, changing participation and access, trends in qualifications and workplace confidence and re-evaluating skills gaps identified in previous surveys. Substantial changes in the archaeological workplace are identifiable with deterioration in employment conditions and an increasingly casualised workforce, contrasting with a growth in professionalisation observed through an increasingly qualified workforce. Restructuring of the discipline observed in previous surveys, showing increases in Indigenous archaeology and a corresponding decrease in other subfields, are less pronounced. Survey data demonstrate the Australian archaeological workforce to be a highly qualified discipline by world standards but also a discipline that is being reshaped by downsizing of government regulation of heritage issues and volatility in the private sector related to external economic factors. -

Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri: MOspace Oral Tradition 1/2 (1986): 231-71 Australian Aboriginal Oral Traditions Margaret Clunies Ross 1. Aboriginal Oral Traditions A History of Research and Scholarship1 The makers of Australian songs, or of the combined songs and dances, are the poets, or bards, of the tribes, and are held in great esteem. Their names are known in the neighboring tribes, and their songs are carried from tribe to tribe, until the very meaning of the words is lost, as well as the original source of the song. It is hard to say how far and how long such a song may travel in the course of time over the Australian continent. (Howitt 1904:414) In 1988 non-Aboriginal Australians will celebrate two hundred years’ occupation of a country which had previously been home to an Aboriginal population of about 300,000 people. They probably spoke more than two hundred different languages and most individuals were multilingual (Dixon 1980). They had a rich culture, whose traditions were centrally concerned with the celebration of three basic types of religious ritual-rites of fertility, initiation, and death (Maddock 1982:105-57). In many parts of Australia, particularly in the south where white settlement was earliest and densest, Aboriginal traditional life has largely disappeared, although the memory of it has been passed down the generations. Nowadays all Aborigines, even in the most traditional parts of the north, such as Arnhem Land, are affected to a greater or lesser extent by the Australian version of Western culture, and must preserve their own traditions by a combination of holding strategies. -

Historical Archaeology in Australia: Historical Or Hysterical? Crisis Or Creative Awakening?

AUSTRALASIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 17, 1999 Historical Archaeology in Australia: Historical or Hysterical? Crisis or Creative Awakening? RICHARD MACKAY and GRACE KARSKENS This paper explores the current state andfuture prospects ofhistorical archaeology in Australia and takes as its starting points issues raised in Graham Connah's 1998 paper 'Pattern and purpose in historical archaeology '. Connah presents a rather narrow version ofhistorical archaeology as a fading 'scholarly discipline' anchored in academia. His assertion that 'a discipline consists very largely ofits body ofpublished material'fails to recognise the growing contribution ofotherforms ofpublic archaeology in Australia in the late twentieth century. We show that recent developments - the dialogue emerging between history and archaeology, the new publications and other media, interestfrom the wider community and recent academic appointments in the discipline - provide a counter-viewpoint and cause for optimism. In revisiting Connah 's main issues from these perspectives, some ofthe real problems and challenges facing the discipline and the profession are also explored. As we peek from behind our piles ofconsultant reports, across massive downsizing, recent new appointments have been made the threshold ofa new millenium, we see historical archaeology in historical archaeology at La Trobe (Melbourne), Flinders in Australia has at last become 'historical' through a new (Adelaide), James Cook (Townsville), Western Australia engagement with history, and has begun to deliver worthwhile (Perth) and Northern Territory University (Darwin). From this and meaningful knowledge to an eager and interested perspective, historical archaeology appears to be doing rather community. better than many other disciplines. It has not so much Withered Some of the work appearing now is at last answering away as moved on.