'Niŋ, -Pi-, -E and -Aa Morphemes in Kuloonay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LCSH Section K

K., Rupert (Fictitious character) Motion of K stars in line of sight Ka-đai language USE Rupert (Fictitious character : Laporte) Radial velocity of K stars USE Kadai languages K-4 PRR 1361 (Steam locomotive) — Orbits Ka’do Herdé language USE 1361 K4 (Steam locomotive) UF Galactic orbits of K stars USE Herdé language K-9 (Fictitious character) (Not Subd Geog) K stars—Galactic orbits Ka’do Pévé language UF K-Nine (Fictitious character) BT Orbits USE Pévé language K9 (Fictitious character) — Radial velocity Ka Dwo (Asian people) K 37 (Military aircraft) USE K stars—Motion in line of sight USE Kadu (Asian people) USE Junkers K 37 (Military aircraft) — Spectra Ka-Ga-Nga script (May Subd Geog) K 98 k (Rifle) K Street (Sacramento, Calif.) UF Script, Ka-Ga-Nga USE Mauser K98k rifle This heading is not valid for use as a geographic BT Inscriptions, Malayan K.A.L. Flight 007 Incident, 1983 subdivision. Ka-houk (Wash.) USE Korean Air Lines Incident, 1983 BT Streets—California USE Ozette Lake (Wash.) K.A. Lind Honorary Award K-T boundary Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary UF Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) K.A. Linds hederspris K-T Extinction Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Moderna museets vänners skulpturpris USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction BT National parks and reserves—Hawaii K-ABC (Intelligence test) K-T Mass Extinction Ka Iwi Scenic Shoreline Park (Hawaii) USE Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children USE Cretaceous-Paleogene Extinction USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-B Bridge (Palau) K-TEA (Achievement test) Ka Iwi Shoreline (Hawaii) USE Koro-Babeldaod Bridge (Palau) USE Kaufman Test of Educational Achievement USE Ka Iwi National Scenic Shoreline (Hawaii) K-BIT (Intelligence test) K-theory Ka-ju-ken-bo USE Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test [QA612.33] USE Kajukenbo K. -

Acte III Une Réforme, Des Questions Une Réforme, Des Questions

N°18 - Août 2015 MAURITANIE PODOR DAGANA Gamadji Sarré Dodel Rosso Sénégal Ndiandane Richard Toll Thillé Boubakar Guédé Ndioum Village Ronkh Gaé Aéré Lao Cas Cas Ross Béthio Mbane Fanaye Ndiayène Mboumba Pendao Golléré SAINT-LOUIS Région de Madina Saldé Ndiatbé SAINT-LOUIS Pété Galoya Syer Thilogne Gandon Mpal Keur Momar Sar Région de Toucouleur MAURITANIE Tessekéré Forage SAINT-LOUIS Rao Agnam Civol Dabia Bokidiawé Sakal Région de Océan LOUGA Léona Nguène Sar Nguer Malal Gandé Mboula Labgar Oréfondé Nabbadji Civol Atlantique Niomré Région de Mbeuleukhé MATAM Pété Ouarack MATAM Kelle Yang-Yang Dodji Gueye Thieppe Bandègne KANEL LOUGA Lougré Thiolly Coki Ogo Ouolof Mbédiène Kamb Géoul Thiamène Diokoul Diawrigne Ndiagne Kanène Cayor Boulal Thiolom KEBEMER Ndiob Thiamène Djolof Ouakhokh Région de Fall Sinthiou Loro Touba Sam LOUGA Bamambé Ndande Sagata Ménina Yabal Dahra Ngandiouf Geth BarkedjiRégion de RANEROU Ndoyenne Orkadiéré Waoundé Sagatta Dioloff Mboro Darou Mbayène Darou LOUGA Khoudoss Semme Méouane Médina Pékesse Mamane Thiargny Dakhar MbadianeActe III Moudéry Taïba Pire Niakhène Thimakha Ndiaye Gourèye Koul Darou Mousty Déali Notto Gouye DiawaraBokiladji Diama Pambal TIVAOUANE de la DécentralisationRégion de Kayar Diender Mont Rolland Chérif Lô MATAM Guedj Vélingara Oudalaye Wourou Sidy Aouré Touba Région de Thiel Fandène Thiénaba Toul Région de Pout Région de DIOURBEL Région de Gassane khombole Région de Région de DAKAR DIOURBEL Keur Ngoundiane DIOURBEL LOUGA MATAM Gabou Moussa Notto Ndiayène THIES Sirah Région de Ballou Ndiass -

LCSH Section J

J (Computer program language) J.G.L. Collection (Australia) New York, N.Y.) BT Object-oriented programming languages BT Painting—Private collections—Australia BT Apartment houses—New York (State) J (Locomotive) (Not Subd Geog) J.G. Strijdomdam (South Africa) Downtown by Philippe Starck (New York, N.Y.) BT Locomotives USE Pongolapoort Dam (South Africa) Office buildings—New York (State) J & R Landfill (Ill.) J. Hampton Robb Residence (New York, N.Y.) J.P. Morgan, Jr., House (New York, N.Y.) UF J and R Landfill (Ill.) USE James Hampden and Cornelia Van Rensselaer USE Phelps Stokes-J.P. Morgan House (New York, J&R Landfill (Ill.) Robb House (New York, N.Y.) N.Y.) BT Sanitary landfills—Illinois J. Herbert W. Small Federal Building and United States J. Paul Getty Center (Los Angeles, Calif.) J. & W. Seligman and Company Building (New York, Courthouse (Elizabeth City, N.C.) USE Getty Center (Los Angeles, Calif.) N.Y.) UF Small Federal Building and United States J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Villa (Malibu, Calif.) USE Banca Commerciale Italiana Building (New Courthouse (Elizabeth City, N.C.) USE Getty Villa (Malibu, Calif.) York, N.Y.) BT Courthouses—North Carolina J. Paul Getty Museum Herb Garden (Malibu, Calif.) J 29 (Jet fighter plane) Public buildings—North Carolina This heading is not valid for use as a geographic USE Saab 29 (Jet fighter plane) J-holomorphic curves subdivision. J.A. Ranch (Tex.) USE Pseudoholomorphic curves UF Getty Museum Herb Garden (Malibu, Calif.) BT Ranches—Texas J. I. Case tractors BT Herb gardens—California J. Alfred Prufrock (Fictitious character) USE Case tractors J. -

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal

Annex H. Summary of the Early Grade Reading Materials Survey in Senegal Geography and Demographics 196,722 square Size: kilometers (km2) Population: 14 million (2015) Capital: Dakar Urban: 44% (2015) Administrative 14 regions Divisions: Religion: 95% Muslim 4% Christian 1% Traditional Source: Central Intelligence Agency (2015). Note: Population and percentages are rounded. Literacy Projected 2013 Primary School 2015 Age Population (aged 2.2 million Literacy a a 7–12 years): Rates: Overall Male Female Adult (aged 2013 Primary School 56% 68% 44% 84%, up from 65% in 1999 >15 years) GER:a Youth (aged 2013 Pre-primary School 70% 76% 64% 15%,up from 3% in 1999 15–24 years) GER:a Language: French Mean: 18.4 correct words per minute When: 2009 Oral Reading Fluency: Standard deviation: 20.6 Sample EGRA Where: 11 regions 18% zero scores Resultsb 11% reading with ≥60% Reading comprehension Who: 687 P3 students Comprehension: 52% zero scores Note: EGRA = Early Grade Reading Assessment; GER = Gross Enrollment Rate; P3 = Primary Grade 3. Percentages are rounded. a Source: UNESCO (2015). b Source: Pouezevara et al. (2010). Language Number of Living Languages:a 210 Major Languagesb Estimated Populationc Government Recognized Statusd 202 DERP in Africa—Reading Materials Survey Final Report 47,000 (L1) (2015) French “Official” language 3.9 million (L2) (2013) “National” language Wolof 5.2 million (L1) (2015) de facto largest LWC Pulaar 3.5 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Serer-Sine 1.4 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Maninkakan (i.e., Malinké) 1.3 million (L1) (2015) “National” language Soninke 281,000 (L1) (2015) “National” language Jola-Fonyi (i.e., Diola) 340,000 (L1) “National” language Balant, Bayot, Guñuun, Hassanya, Jalunga, Kanjaad, Laalaa, Mandinka, Manjaaku, “National” languages Mankaañ, Mënik, Ndut, Noon, __ Oniyan, Paloor, and Saafi- Saafi Note: L1 = first language; L2 = second language; LWC = language of wider communication. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

Actes De L'atelier ATELIER REGIONAL D'echanges SUR L

ATELIER REGIONAL D’ECHANGES SUR L’AMENAGEMENT DES VALLEES EN CASAMANCE : Ziguinchor, 16 et 17 décembre 2008 Actes de l'atelier Partenaires techniques : Partenaires financiers : ACPP ARD Ziguinchor CRCR Fondaon Lord GRDR Michelham of Hellingly GRDR Ziguinchor - Rue Emile Badiane - BP 813 Ziguinchor - (221) 33 991 27 82 - [email protected] http://www.grdr.org SOMMAIRE PREMIER JOUR : FOIRE D’ECHANGES PAYSANS SUR L’AMENAGEMENT DES VALLEES EN CASAMANCE p. 3 ‐ 6 Cérémonie officielle d’ouverture 3 Echanges de savoirs et d’expériences 4 Lutte contre la mouche blanche des mangues – CARE SENEGAL 4 Techniques de greffage – ANCAR 5 Modèle de gestion des ouvrages – comité vallée Diattock 5 Compagnie Bousana 5 Débats 5 Techniques de lutte biologique par Camara et Diatta 6 DEUXIEME JOUR : ATELIER REGIONAL D’ECHANGES SUR L’AMENAGEMENT DES VALLEES EN CASAMANCE p. 7 – 21 I. LA FILIERE SEMENCE DE RIZ Programme concerté d’appui au développement de la filière"semences certifiées de 7 riz" en Casamance Construction d’une filière semence de riz basée sur les acteurs locaux 8 Débats avec la salle 9 II. PERENISATION DES COMITES VALLEES ET IMPACTS DES AMENAGEMENTS VALLEES Gestion des Comités Vallée 12 Evaluation du système de désalinisation, prospective sur les possibilités de 13 protection et restauration de la mangrove dans la zone d’intervention du GRDR Débats avec la salle 14 III. ATELIERS DE REFLEXION Atelier 1 : filière riz ‐ entre production et certification de semences 17 Atelier 2 : les comites vallées : quelle pérennisation ? 19 Atelier 3 : impact des -

Ransoming, Collateral, and Protective Captivity on the Upper Guinea Coast Before 1650: Colonial Continuities, Contemporary Echoes1

MAX PLANCK INSTITUTE FOR SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY WORKING PAPERS WORKING PAPER NO. 193 PETER MARK RANSOMING, COLLATERAL, AND PROTECTIVE CAPTIVITY ON THE UppER GUINEA COAST BEFORE 1650: COLONIAL CONTINUITIES, Halle / Saale 2018 CONTEMPORARY ISSN 1615-4568 ECHOES Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology, PO Box 110351, 06017 Halle / Saale, Phone: +49 (0)345 2927- 0, Fax: +49 (0)345 2927- 402, http://www.eth.mpg.de, e-mail: [email protected] Ransoming, Collateral, and Protective Captivity on the Upper Guinea Coast before 1650: colonial continuities, contemporary echoes1 Peter Mark2 Abstract This paper investigates the origins of pawning in European-African interaction along the Upper Guinea Coast. Pawning in this context refers to the holding of human beings as security for debt or to ensure that treaty obligations be fulfilled. While pawning was an indigenous practice in Upper Guinea, it is proposed here that when the Portuguese arrived in West Africa, they were already familiar with systems of ransoming, especially of members of the nobility. The adoption of pawning and the associated practice of not enslaving members of social elites may be explained by the fact that these customs were already familiar to both the Portuguese and their West African hosts. Vestiges of these social institutions may be found well into the colonial period on the Upper Guinea Coast. 1 The author expresses his gratitude to Jacqueline Knörr and to the Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology for the opportunity to carry out the research and writing of this paper. Thanks are also due to the members of the Research Group “Integration and Conflict along the Upper Guinea Coast (West Africa)”, to Marek Mikuš for his comments on an earlier draft, and to Alex Dupuy of Wesleyan University for his insightful comments. -

Cdm-Ar-Pdd) (Version 05)

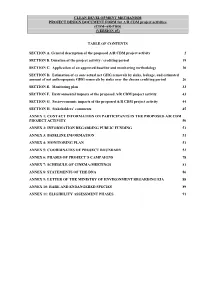

CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM for A/R CDM project activities (CDM-AR-PDD) (VERSION 05) TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 2 SECTION B. Duration of the project activity / crediting period 19 SECTION C. Application of an approved baseline and monitoring methodology 20 SECTION D. Estimation of ex ante actual net GHG removals by sinks, leakage, and estimated amount of net anthropogenic GHG removals by sinks over the chosen crediting period 26 SECTION E. Monitoring plan 33 SECTION F. Environmental impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 43 SECTION G. Socio-economic impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 44 SECTION H. Stakeholders’ comments 45 ANNEX 1: CONTACT INFORMATION ON PARTICIPANTS IN THE PROPOSED A/R CDM PROJECT ACTIVITY 50 ANNEX 2: INFORMATION REGARDING PUBLIC FUNDING 51 ANNEX 3: BASELINE INFORMATION 51 ANNEX 4: MONITORING PLAN 51 ANNEX 5: COORDINATES OF PROJECT BOUNDARY 52 ANNEX 6: PHASES OF PROJECT´S CAMPAIGNS 78 ANNEX 7: SCHEDULE OF CINEMA-MEETINGS 81 ANNEX 8: STATEMENTS OF THE DNA 86 ANNEX 9: LETTER OF THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT REGARDING EIA 88 ANNEX 10: RARE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES 89 ANNEX 11: ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT PHASES 91 SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity A.1. Title of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> Title: Oceanium mangrove restoration project Version of the document: 01 Date of the document: November 10 2010. A.2. Description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> The proposed A/R CDM project activity plans to establish 1700 ha of mangrove plantations on currently degraded wetlands in the Sine Saloum and Casamance deltas, Senegal. -

Alice Joyce Hamer a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degre

TRADITION AND CHANGE: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF DIOLA WOMEN (SOUTHWEST SENEGAL) IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Alice Joyce Hamer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfullment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan c'7 1983 Doctoral Committee: Professor Louise A. Tilly, Co-chair Professor Godfrey N. Uzoigwe, Co-Chair -Assistant Professor Hemalata Dandekar Professor Thomas Holt women in Dnv10rnlomt .... f.-0 1-; .- i i+, on . S•, -.----------------- ---------------------- ---- WOMEN'S STUDIES PROGRAM THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 354 LORCH HALL ANN ARB R, MICHIGAN 48109 (313) 763-2047 August 31, 1983 Ms. Debbie Purcell Office of Women in Development Room 3534 New State Agency of International Development Washington, D.C. 20523 Dear Ms. Purcell, Yesterday I mailed a copy of my dissertation to you, and later realized that I neglected changirg the pages where the maps should be located. The copy in which you are hopefully in receipt was run off by a computer, which places a blank page in where maps belong to hold their place. I am enclosing the maps so that you can insert them. My apologies for any inconvenience that this may have caused' you. Sincerely, 1 i(L 11. Alice Hamer To my sister Faye, and to my mother and father who bore her ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Numerous people in both Africa and America were instrumental in making this dissertation possible. Among them were those in Senegal who helped to make my experience in Senegal an especially rich one. I cannot emphasize enough my gratitude to Professor Lucie Colvin who honored me by making me a part of her distinguished research team that studied migration in the Senegambia. -

Demographics of Senegal: Ethnicity and Religion (By Region and Department in %)

Appendix 1 Demographics of Senegal: Ethnicity and Religion (By Region and Department in %) ETHNICITY Wolof Pulaar Jola Serer Mandinka Other NATIONAL 42.7 23.7 5.3 14.9 4.2 13.4 Diourbel: 66.7 6.9 0.2 24.8 0.2 1.2 Mbacke 84.9 8.4 0.1 8.4 0.1 1.1 Bambey 57.3 2.9 0.1 38.9 0.1 0.7 Diourbel 53.4 9.4 0.4 34.4 0.5 1.9 Saint-Louis: 30.1 61.3 0.3 0.7 0.0 7.6 Matam 3.9 88.0 0.0 1.0 0.0 8.0 Podor 5.5 89.8 0.3 0.3 0.0 4.1 Dagana 63.6 25.3 0.7 1.3 0.0 10.4 Ziguinchor: 10.4 15.1 35.5 4.5 13.7 20.8 Ziguinchor 8.2 13.5 34.5 3.4 14.4 26.0 Bignona 1.8 5.2 80.6 1.2 6.1 5.1 Oussouye 4.8 4.7 82.4 3.5 1.5 3.1 Dakar 53.8 18.5 4.7 11.6 2.8 8.6 Fatick 29.9 9.2 0.0 55.1 2.1 3.7 Kaolack 62.4 19.3 0.0 11.8 0.5 6.0 Kolda 3.4 49.5 5.9 0.0 23.6 17.6 Louga 70.1 25.3 0.0 1.2 0.0 3.4 Tamba 8.8 46.4 0.0 3.0 17.4 24.4 Thies 54.0 10.9 0.7 30.2 0.9 3.3 Continued 232 Appendix 1 Appendix 1 (continued) RELIGION Tijan Murid Khadir Other Christian Traditional Muslim NATIONAL 47.4 30.1 10.9 5.4 4.3 1.9 Diourbel: 9.5 85.3 0.0 4.1 0.0 0.3 Mbacke 4.3 91.6 3.7 0.0 0.0 0.2 Bambey 9.8 85.6 2.9 0.6 0.7 0.4 Diourbel 16.0 77.2 4.6 0.7 1.2 0.3 Saint-Louis: 80.2 6.4 8.4 3.7 0.4 0.9 Matam 88.6 2.3 3.0 4.7 0.3 1.0 Podor 93.8 1.9 2.4 0.8 0.0 1.0 Dagana 66.2 11.9 15.8 0.9 0.8 1.1 Ziguinchor: 22.9 4.0 32.0 16.3 17.1 7.7 Ziguinchor 31.2 5.0 17.6 16.2 24.2 5.8 Bignona 17.0 3.3 51.2 18.5 8.2 1.8 Oussouye 14.6 2.5 3.3 6.1 27.7 45.8 Dakar 51.5 23.4 6.9 10.9 6.7 0.7 Fatick 39.6 38.6 12.4 1.2 7.8 0.5 Kaolack 65.3 27.2 4.9 0.9 1.0 0.6 Kolda 52.7 3.6 26.0 11.1 5.0 1.6 Louga 37.3 45.9 15.1 1.2 0.1 0.5 Source: -

The Morphology and Syntax of Ergativity

THE MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF ERGATIVITY: A TYPOLOGICAL APPROACH by Justin Rill A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics Winter 2017 © 2017 Justin Rill All Rights Reserved ProQuest Number:10257594 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ProQuest 10257594 Published by ProQuest LLC ( 2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346 THE MORPHOLOGY AND SYNTAX OF ERGATIVITY: A TYPOLOGICAL APPROACH by Justin Rill Approved: Benjamin Bruening, Ph.D. Chair of the Department of Linguistics and Cognitive Science Approved: George H. Watson, Ph.D. Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Approved: Ann L. Ardis, Ph.D. Senior Vice Provost for Graduate and Professional Education I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dis- sertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Signed: Gabriella Hermon, Ph.D. Professor in charge of dissertation I certify that I have read this dissertation and that in my opinion it meets the academic and professional standard required by the University as a dis- sertation for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

The Mouvement Des Forces Démocratiques De Casamance: the Illusion of Separatism in Senegal? Vincent Foucher

The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal? Vincent Foucher To cite this version: Vincent Foucher. The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Sepa- ratism in Senegal?. Lotje de Vries; Pierre Englebert; Mareike Schomerus. Secessionism in African Politics, Palgrave Macmillan, pp.265-292, 2018, Palgrave Series in African Borderlands Studies, 978- 3-319-90206-7. 10.1007/978-3-319-90206-7_10. halshs-02479100 HAL Id: halshs-02479100 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02479100 Submitted on 12 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHAPTER 10 The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal? Vincent Foucher INTRODUCTiON On December 26, 1982, the Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC) voiced for the first time its demand for the indepen- dence of Casamance, the southern region of Senegal. This demand launched the longest, currently running violent conflict in Africa. The MFDC can thus lay claim to having led Africa’s second “secessionist moment”1 of the 1980s, after the first secessionist phase of the 1960s. Over the years, the Casamance conflict has killed several thousand people.