Alice Joyce Hamer a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concours Direct Cycle a Option "Diplomatie Arabisant"

N° de Date de Prénom(s) Nom Lieu de naissance table naissance 1 Abdel Kader AGNE 01/03/1989 Diourbel 2 Dieng AIDA 01/01/1991 Pattar 3 Adjaratou Sira AIDARA 02/01/1988 Dakar 4 Alimatou Sadiya AIDARA 06/01/1992 Thiès 5 Marieme AIDARA 06/02/1991 Nioro Du Rip 6 Mouhamadou Moustapha AIDARA 28/09/1991 Touba 7 Ndeye Maguette Laye ANE 10/06/1995 Dakar 8 Sileye ANNE 10/06/1993 Boinadji Roumbe 9 Tafsir Baba ANNE 19/12/1993 Rufisque 10 Gerard Siabito ASSINE 03/10/1991 Samatite 11 Tamba ATHIE 19/08/1988 Colibantan 12 Papa Ousseynou Samba AW 02/11/1992 Thiès Laobe 13 Ababacar BA 02/09/1991 Pikine 14 Abdou Aziz BA 08/02/1992 Rufisque 15 Abdoul BA 02/02/1992 Keur Birane Dia 16 Abdoul Aziz BA 22/11/1994 Ourossogui 17 Abdoul Mamadou BA 30/08/1992 Thiaroye Gare 18 Abdrahmane Baidy BA 10/02/1991 Sinthiou Bamambe 19 Abibatou BA 08/08/1992 Dakar 20 Aboubacry BA 01/01/1995 Dakar 21 Adama Daouda BA 08/04/1995 Matam 22 Ahmet Tidiane BA 22/02/1991 Mbour 23 Aliou Abdoul BA 26/05/1993 Goudoude Ndouetbe 24 Aly BA 20/01/1988 Saint-Louis 25 Amadou BA 01/12/1996 Ngothie 26 Amidou BA 06/12/1991 Pikine 27 Arona BA 02/10/1989 Fandane 28 Asmaou BA 03/10/1991 Dakar 29 Awa BA 01/03/1990 Dakar 30 Babacar BA 01/06/1990 Ngokare Ka 2 31 Cheikh Ahmed Tidiane BA 03/06/1990 Nioro Du Rip 32 Daouda BA 23/08/1990 Kolda 33 Demba Alhousseynou BA 06/12/1990 Thille -Boubacar 34 Dieynaba BA 01/01/1995 Dakar 35 Dior BA 17/07/1995 Dakar 36 El Hadji Salif BA 04/11/1988 Diamaguene 37 Fatimata BA 20/06/1993 Tivaouane 38 Fatma BA 12/01/1988 Dakar 39 Fatou BA 02/02/1996 Guediawaye 40 Fatou Bintou -

Acte III Une Réforme, Des Questions Une Réforme, Des Questions

N°18 - Août 2015 MAURITANIE PODOR DAGANA Gamadji Sarré Dodel Rosso Sénégal Ndiandane Richard Toll Thillé Boubakar Guédé Ndioum Village Ronkh Gaé Aéré Lao Cas Cas Ross Béthio Mbane Fanaye Ndiayène Mboumba Pendao Golléré SAINT-LOUIS Région de Madina Saldé Ndiatbé SAINT-LOUIS Pété Galoya Syer Thilogne Gandon Mpal Keur Momar Sar Région de Toucouleur MAURITANIE Tessekéré Forage SAINT-LOUIS Rao Agnam Civol Dabia Bokidiawé Sakal Région de Océan LOUGA Léona Nguène Sar Nguer Malal Gandé Mboula Labgar Oréfondé Nabbadji Civol Atlantique Niomré Région de Mbeuleukhé MATAM Pété Ouarack MATAM Kelle Yang-Yang Dodji Gueye Thieppe Bandègne KANEL LOUGA Lougré Thiolly Coki Ogo Ouolof Mbédiène Kamb Géoul Thiamène Diokoul Diawrigne Ndiagne Kanène Cayor Boulal Thiolom KEBEMER Ndiob Thiamène Djolof Ouakhokh Région de Fall Sinthiou Loro Touba Sam LOUGA Bamambé Ndande Sagata Ménina Yabal Dahra Ngandiouf Geth BarkedjiRégion de RANEROU Ndoyenne Orkadiéré Waoundé Sagatta Dioloff Mboro Darou Mbayène Darou LOUGA Khoudoss Semme Méouane Médina Pékesse Mamane Thiargny Dakhar MbadianeActe III Moudéry Taïba Pire Niakhène Thimakha Ndiaye Gourèye Koul Darou Mousty Déali Notto Gouye DiawaraBokiladji Diama Pambal TIVAOUANE de la DécentralisationRégion de Kayar Diender Mont Rolland Chérif Lô MATAM Guedj Vélingara Oudalaye Wourou Sidy Aouré Touba Région de Thiel Fandène Thiénaba Toul Région de Pout Région de DIOURBEL Région de Gassane khombole Région de Région de DAKAR DIOURBEL Keur Ngoundiane DIOURBEL LOUGA MATAM Gabou Moussa Notto Ndiayène THIES Sirah Région de Ballou Ndiass -

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

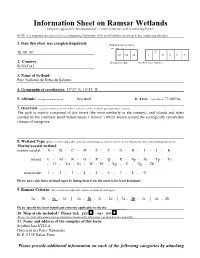

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10. -

'Niŋ, -Pi-, -E and -Aa Morphemes in Kuloonay

The prefix ni- in Kuloonaay: grammaticalization pathways in a three-morpheme system By David C. Lowry August 2015 Word Count: 19,719 Presented as part of the requirement of the MA Degree in Field Linguistics, Centre for Linguistics, Translation & Literacy, Redcliffe College. DECLARATION This dissertation is the product of my own work. I declare also that the dissertation is available for photocopying, reference purposes and Inter-Library Loan. David Christopher Lowry 2 ABSTRACT Title: The prefix ni- in Kuloonaay: grammaticalization pathways in a three- morpheme system. Author: David C. Lowry Date: August 2015 The prefix ni- is the most common particle in the verbal system of Jola Kuloonaay, an Atlantic language of Senegal and The Gambia. Its complex distribution has made it difficult to classify, and a variety of labels have been proposed in the literature. Other authors writing on Kuloonaay and on related Jola languages have described this prefix in terms of a single morpheme whose distribution follows an eclectic list of rules for which the synchronic motivation is not obvious. An alternative approach, presented here, is to describe the ni- prefix in terms of three distinct morphemes, each following a simple set of rules within a restricted domain. This study explores the three-morpheme hypothesis from both a synchronic and a diachronic perspective. At a synchronic level, a small corpus of narrative texts is used to verify that the model proposed corresponds to the behaviour of ni- in natural text. At a diachronic level, data from a selection of other Jola languages is drawn upon in order to gain insight into the grammaticalization pathways by which the three morpheme ni- system may have evolved. -

Les Resultats Aux Examens

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple - Un But - Une Foi Ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur, de la Recherche et de l’Innovation Université Cheikh Anta DIOP de Dakar OFFICE DU BACCALAUREAT B.P. 5005 - Dakar-Fann – Sénégal Tél. : (221) 338593660 - (221) 338249592 - (221) 338246581 - Fax (221) 338646739 Serveur vocal : 886281212 RESULTATS DU BACCALAUREAT SESSION 2017 Janvier 2018 Babou DIAHAM Directeur de l’Office du Baccalauréat 1 REMERCIEMENTS Le baccalauréat constitue un maillon important du système éducatif et un enjeu capital pour les candidats. Il doit faire l’objet d’une réflexion soutenue en vue d’améliorer constamment son organisation. Ainsi, dans le souci de mettre à la disposition du monde de l’Education des outils d’évaluation, l’Office du Baccalauréat a réalisé ce fascicule. Ce fascicule représente le dix-septième du genre. Certaines rubriques sont toujours enrichies avec des statistiques par type de série et par secteur et sous - secteur. De même pour mieux coller à la carte universitaire, les résultats sont présentés en cinq zones. Le fascicule n’est certes pas exhaustif mais les utilisateurs y puiseront sans nul doute des informations utiles à leur recherche. Le Classement des établissements est destiné à satisfaire une demande notamment celle de parents d'élèves. Nous tenons à témoigner notre sincère gratitude aux autorités ministérielles, rectorales, académiques et à l’ensemble des acteurs qui ont contribué à la réussite de cette session du Baccalauréat. Vos critiques et suggestions sont toujours les bienvenues et nous aident -

Actes De L'atelier ATELIER REGIONAL D'echanges SUR L

ATELIER REGIONAL D’ECHANGES SUR L’AMENAGEMENT DES VALLEES EN CASAMANCE : Ziguinchor, 16 et 17 décembre 2008 Actes de l'atelier Partenaires techniques : Partenaires financiers : ACPP ARD Ziguinchor CRCR Fondaon Lord GRDR Michelham of Hellingly GRDR Ziguinchor - Rue Emile Badiane - BP 813 Ziguinchor - (221) 33 991 27 82 - [email protected] http://www.grdr.org SOMMAIRE PREMIER JOUR : FOIRE D’ECHANGES PAYSANS SUR L’AMENAGEMENT DES VALLEES EN CASAMANCE p. 3 ‐ 6 Cérémonie officielle d’ouverture 3 Echanges de savoirs et d’expériences 4 Lutte contre la mouche blanche des mangues – CARE SENEGAL 4 Techniques de greffage – ANCAR 5 Modèle de gestion des ouvrages – comité vallée Diattock 5 Compagnie Bousana 5 Débats 5 Techniques de lutte biologique par Camara et Diatta 6 DEUXIEME JOUR : ATELIER REGIONAL D’ECHANGES SUR L’AMENAGEMENT DES VALLEES EN CASAMANCE p. 7 – 21 I. LA FILIERE SEMENCE DE RIZ Programme concerté d’appui au développement de la filière"semences certifiées de 7 riz" en Casamance Construction d’une filière semence de riz basée sur les acteurs locaux 8 Débats avec la salle 9 II. PERENISATION DES COMITES VALLEES ET IMPACTS DES AMENAGEMENTS VALLEES Gestion des Comités Vallée 12 Evaluation du système de désalinisation, prospective sur les possibilités de 13 protection et restauration de la mangrove dans la zone d’intervention du GRDR Débats avec la salle 14 III. ATELIERS DE REFLEXION Atelier 1 : filière riz ‐ entre production et certification de semences 17 Atelier 2 : les comites vallées : quelle pérennisation ? 19 Atelier 3 : impact des -

And the Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects

VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF CENTRAL COASTAL SENEGAL (SALOUM) AND THE GAMBIA MARINE COAST AND ESTUARY TO CLIMATE CHANGE INDUCED EFFECTS Consolidated Report GAMBIA- SENEGAL SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES PROJECT (USAID/BA NAFAA) April 2012 Banjul, The Gambia This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website at http://www.crc.uri.edu. For more information contact: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett Bay Campus, South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA. Tel: 401) 874-6224; Fax: 401) 789-4670; Email: [email protected] Citation: Dia Ibrahima, M. (2012). Vulnerability Assessment of Central Coast Senegal (Saloum) and The Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects. Coastal Resources Center and WWF-WAMPO, University of Rhode Island, pp. 40 Disclaimer: This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cooperative Agreement # 624-A-00-09-00033-00. ii Abbreviations CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CIA Central Intelligence Agency CMS Convention on Migratory Species, CSE Centre de Suivi Ecologique DoFish Department of Fisheries DPWM Department Of Parks and Wildlife Management EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone ETP Evapotranspiration FAO United Nations Organization for Food and Agriculture GIS Geographic Information System ICAM II Integrated Coastal and marine Biodiversity management Project IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IUCN International Union for the Conservation of nature NAPA National Adaptation Program of Action NASCOM National Association for Sole Fisheries Co-Management Committee NGO Non-Governmental Organization PA Protected Area PRA Participatory Rapid Appraisal SUCCESS USAID/URI Cooperative Agreement on Sustainable Coastal Communities and Ecosystems UNFCCC Convention on Climate Change URI University of Rhode Island USAID U.S. -

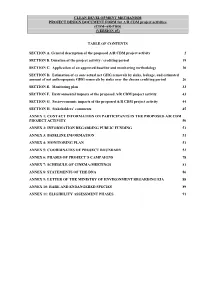

Cdm-Ar-Pdd) (Version 05)

CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM PROJECT DESIGN DOCUMENT FORM for A/R CDM project activities (CDM-AR-PDD) (VERSION 05) TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 2 SECTION B. Duration of the project activity / crediting period 19 SECTION C. Application of an approved baseline and monitoring methodology 20 SECTION D. Estimation of ex ante actual net GHG removals by sinks, leakage, and estimated amount of net anthropogenic GHG removals by sinks over the chosen crediting period 26 SECTION E. Monitoring plan 33 SECTION F. Environmental impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 43 SECTION G. Socio-economic impacts of the proposed A/R CDM project activity 44 SECTION H. Stakeholders’ comments 45 ANNEX 1: CONTACT INFORMATION ON PARTICIPANTS IN THE PROPOSED A/R CDM PROJECT ACTIVITY 50 ANNEX 2: INFORMATION REGARDING PUBLIC FUNDING 51 ANNEX 3: BASELINE INFORMATION 51 ANNEX 4: MONITORING PLAN 51 ANNEX 5: COORDINATES OF PROJECT BOUNDARY 52 ANNEX 6: PHASES OF PROJECT´S CAMPAIGNS 78 ANNEX 7: SCHEDULE OF CINEMA-MEETINGS 81 ANNEX 8: STATEMENTS OF THE DNA 86 ANNEX 9: LETTER OF THE MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT REGARDING EIA 88 ANNEX 10: RARE AND ENDANGERED SPECIES 89 ANNEX 11: ELIGIBILITY ASSESSMENT PHASES 91 SECTION A. General description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity A.1. Title of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> Title: Oceanium mangrove restoration project Version of the document: 01 Date of the document: November 10 2010. A.2. Description of the proposed A/R CDM project activity: >> The proposed A/R CDM project activity plans to establish 1700 ha of mangrove plantations on currently degraded wetlands in the Sine Saloum and Casamance deltas, Senegal. -

Full-Text (PDF)

Vol. 12(2), pp. 46-64, April-June 2020 DOI: 10.5897/JENE2019.0793 Article Number: FB932D163590 ISSN 2006-9847 Copyright © 2020 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article Journal of Ecology and The Natural Environment http://www.academicjournals.org/JENE Full Length Research Paper Customs and traditional management practices of coastal marine natural resources in Lower Casamance: Perspectives of valorisation of endogenous knowledge Claudette Soumbane Diatta1*, Amadou Abdoul Sow1 and Malick Diouf2 1Department of Geography, Faculty of Human Letters and Sciences (Faculty of Arts), University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar (UCAD), Senegal. 2Department of Biology Animal, Sciences of Technologies Faculty, Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture (IUPA), University Cheikh Anta Diop of Dakar (UCAD), Senegal. Received 1 September, 2019; Accepted 25 March, 2020 In southern Senegal, specifically in Lower Casamance, many marine and coastal resources are of significant sociological importance for Jola populations. They are essential both for worship and for sustenance. Thus, through different customs and practices, the Jola helps to preserve their natural environment, even if their primary motivations were hardly conservation. Perceptions, beliefs, and avoidance practices with regard to different types of places and resources decreed sacred, as well as the symbolism of certain animal or plant resources, indicate the very identity of the people. However, with respect to these sociocultural customs and practices, some are specifically aimed at preserving certain resources for economic and ecological interests. This article proposes an analysis of the contribution of Jola traditions and practices in the conservation of marine and coastal resources. To this end, the methodological approach was based on the principles, methods and tools of the participatory approach. -

Mémoire De Confirmation

REPUBLIQUE DU SÉNÉGAL MINISTERE DE L’AGRICULTURE INSTITUT SÉNÉGALAIS DE RECHFRCHES AGRICOLES MÉMOIRE DE CONFIRMATION présentépar Dr Cheikh Oumar BA Sociologue sousla Direction du Professeur Abdoulaye Bara DIOP Sur Migrations et organisations paysannes en Basse Casamance. Une première caractérisation à partir de l’exemple du village de Sue1 (Département de Bignona). Juin 1997 SOMMAIRE PAGE DE GARDE . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. SOMMAIRE ............................................................................................................................. 2 L., LISTE DES SIGLES................................................................................................................. 3:t: 5& AVANT-PROPOS.................................................................................................................... s 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................ S#i f 2. PREMIERE PARTIE : PRESENTATIONDE LA ZONE D’ETUDE ........................... 12 2.1. Organisationsociale Diola . .. .. .. .. .. .. .. ..*.................................. 13 2.2. Suel,un village typiquedu phénomènede mandinguisation.,..... .. .. ,.. ,, . .. .., 16 3. DEUXIEME PARTIE : CADRE THEORIQUE . .. ..*...............*....................................*... 19 3.1. État de la question.. .. ..f........... 19 3.2. Problématique. ..<....................................................*..............................,...,.*...........*....27 3.3. Méthodologie. ..~.............................................................f.................................. -

The Mouvement Des Forces Démocratiques De Casamance: the Illusion of Separatism in Senegal? Vincent Foucher

The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal? Vincent Foucher To cite this version: Vincent Foucher. The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Sepa- ratism in Senegal?. Lotje de Vries; Pierre Englebert; Mareike Schomerus. Secessionism in African Politics, Palgrave Macmillan, pp.265-292, 2018, Palgrave Series in African Borderlands Studies, 978- 3-319-90206-7. 10.1007/978-3-319-90206-7_10. halshs-02479100 HAL Id: halshs-02479100 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02479100 Submitted on 12 Mar 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHAPTER 10 The Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance: The Illusion of Separatism in Senegal? Vincent Foucher INTRODUCTiON On December 26, 1982, the Mouvement des Forces Démocratiques de Casamance (MFDC) voiced for the first time its demand for the indepen- dence of Casamance, the southern region of Senegal. This demand launched the longest, currently running violent conflict in Africa. The MFDC can thus lay claim to having led Africa’s second “secessionist moment”1 of the 1980s, after the first secessionist phase of the 1960s. Over the years, the Casamance conflict has killed several thousand people.