Measurement and Research Support to Education Strategy Goal 1 Senegal Behavior Change Communication Research: Kaolack Endline Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10. -

And the Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects

VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT OF CENTRAL COASTAL SENEGAL (SALOUM) AND THE GAMBIA MARINE COAST AND ESTUARY TO CLIMATE CHANGE INDUCED EFFECTS Consolidated Report GAMBIA- SENEGAL SUSTAINABLE FISHERIES PROJECT (USAID/BA NAFAA) April 2012 Banjul, The Gambia This publication is available electronically on the Coastal Resources Center’s website at http://www.crc.uri.edu. For more information contact: Coastal Resources Center, University of Rhode Island, Narragansett Bay Campus, South Ferry Road, Narragansett, Rhode Island 02882, USA. Tel: 401) 874-6224; Fax: 401) 789-4670; Email: [email protected] Citation: Dia Ibrahima, M. (2012). Vulnerability Assessment of Central Coast Senegal (Saloum) and The Gambia Marine Coast and Estuary to Climate Change Induced Effects. Coastal Resources Center and WWF-WAMPO, University of Rhode Island, pp. 40 Disclaimer: This report was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Cooperative Agreement # 624-A-00-09-00033-00. ii Abbreviations CBD Convention on Biological Diversity CIA Central Intelligence Agency CMS Convention on Migratory Species, CSE Centre de Suivi Ecologique DoFish Department of Fisheries DPWM Department Of Parks and Wildlife Management EEZ Exclusive Economic Zone ETP Evapotranspiration FAO United Nations Organization for Food and Agriculture GIS Geographic Information System ICAM II Integrated Coastal and marine Biodiversity management Project IPCC Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change IUCN International Union for the Conservation of nature NAPA National Adaptation Program of Action NASCOM National Association for Sole Fisheries Co-Management Committee NGO Non-Governmental Organization PA Protected Area PRA Participatory Rapid Appraisal SUCCESS USAID/URI Cooperative Agreement on Sustainable Coastal Communities and Ecosystems UNFCCC Convention on Climate Change URI University of Rhode Island USAID U.S. -

Alice Joyce Hamer a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfullment of the Requirements for the Degre

TRADITION AND CHANGE: A SOCIAL HISTORY OF DIOLA WOMEN (SOUTHWEST SENEGAL) IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Alice Joyce Hamer A dissertation submitted in partial fulfullment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan c'7 1983 Doctoral Committee: Professor Louise A. Tilly, Co-chair Professor Godfrey N. Uzoigwe, Co-Chair -Assistant Professor Hemalata Dandekar Professor Thomas Holt women in Dnv10rnlomt .... f.-0 1-; .- i i+, on . S•, -.----------------- ---------------------- ---- WOMEN'S STUDIES PROGRAM THE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN 354 LORCH HALL ANN ARB R, MICHIGAN 48109 (313) 763-2047 August 31, 1983 Ms. Debbie Purcell Office of Women in Development Room 3534 New State Agency of International Development Washington, D.C. 20523 Dear Ms. Purcell, Yesterday I mailed a copy of my dissertation to you, and later realized that I neglected changirg the pages where the maps should be located. The copy in which you are hopefully in receipt was run off by a computer, which places a blank page in where maps belong to hold their place. I am enclosing the maps so that you can insert them. My apologies for any inconvenience that this may have caused' you. Sincerely, 1 i(L 11. Alice Hamer To my sister Faye, and to my mother and father who bore her ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Numerous people in both Africa and America were instrumental in making this dissertation possible. Among them were those in Senegal who helped to make my experience in Senegal an especially rich one. I cannot emphasize enough my gratitude to Professor Lucie Colvin who honored me by making me a part of her distinguished research team that studied migration in the Senegambia. -

Carte Administrative De La Région De Kaolack

Carte administrative de la région de Kaolack Extrait du Au Senegal http://www.au-senegal.com/carte-administrative-de-la-region-de-kaolack,034.html Kaolack Carte administrative de la région de Kaolack - Recherche - Découvrir le Sénégal, pays de la teranga - Sénégal administratif - Date de mise en ligne : jeudi 21 juin 2012 Au Senegal Copyright © Au Senegal Page 1/4 Carte administrative de la région de Kaolack Découpage administratif de la région de Kaolack Collectivités locales de la région de Kaolack D'après ministère de l'Intérieur, 2012 Région Département Commune Communauté rurale KAOLACK GUINGUINEO DARA MBOSS KAOLACK GUINGUINEO KHELCOM BIRAME KAOLACK GUINGUINEO MBADAKHOUNE KAOLACK GUINGUINEO NDIAGO KAOLACK GUINGUINEO NGAGNICK KAOLACK GUINGUINEO NGATHIE NAOUDE KAOLACK GUINGUINEO NGELLOU KAOLACK GUINGUINEO OUROUR KAOLACK GUINGUINEO PANAL WOLOF KAOLACK GUINGUINEO FASS KAOLACK GUINGUINEO GUINGUINEO KAOLACK GUINGUINEO MBOSS KAOLACK KAOLACK DYA KAOLACK KAOLACK KEUR BAKA KAOLACK KAOLACK KEUR SOCE KAOLACK KAOLACK LATMINGUE KAOLACK KAOLACK NDIAFFATE KAOLACK KAOLACK NDIEBEL KAOLACK KAOLACK NDIEDIENG KAOLACK KAOLACK THIARE KAOLACK KAOLACK THIOMBY Copyright © Au Senegal Page 2/4 Carte administrative de la région de Kaolack KAOLACK KAOLACK GANDIAYE KAOLACK KAOLACK KAHONE KAOLACK KAOLACK KAOLACK KAOLACK KAOLACK NDOFFANE KAOLACK KAOLACK SIBASSOR KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP DABALY KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP DAROU SALAM KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP GAINTE KAYE KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP KAYEMOR KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP KEUR MABA DIAKHOU KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP KEUR MADONGO KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP MEDINA SABAKH KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP NDRAME ESCALE KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP NGAYENE KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP PAOSKOTO KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP POROKHANE KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP TAIBA NIASSENE KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP WACK NGOUNA KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP KEUR MADIABEL KAOLACK NIORO DU RIP NIORO DU RIP Post-scriptum : Carte 2010 réalisée avec l'aimable concours de Performances Copyright © Au Senegal Page 3/4 Carte administrative de la région de Kaolack Copyright © Au Senegal Page 4/4. -

Stephen Burman

SENEGALESE ISLAM: OLD STRENGTHS, NEW CHALLENGES KEY POINTS Islam in Senegal is based around sufi brotherhoods. These have substantial connections across West Africa, including Mali, as well as in North Africa, including Morocco and Algeria. They are extremely popular and historically closely linked to the state. Salafism has had a small presence since the mid-twentieth century. Established Islam in Senegal has lately faced new challenges: o President Wade’s (2000-2012) proximity to the sufi brotherhoods strained the division between the state and religion and compromised sufi legitimacy. o A twin-track education system. The state has a limited grip on the informal education sector, which is susceptible to extremist teaching. o A resurgence of salafism, evidenced by the growing influence of salafist community organisations and reports of support from the Gulf. o Events in Mali and Senegal’s support to the French-led intervention have led to greater questioning about the place of Islam in regional identity. Senegal is therefore vulnerable to growing Islamist extremism. Its institutions and sufi brotherhoods put it in a strong position to resist it, but this should not be taken for granted. DETAIL Mali, 2012. Reports on the jihadist takeover of the North include references to around 20 speakers of Wolof, a language whose native speakers come almost exclusively from Senegal. Earlier reporting refers to a Senegalese contingent among the jihadist kidnappers of Canadian diplomat Robert Fowler. These and other reports (such as January 2013 when an imam found near the Senegal-Mali border was arrested for jihadist links) put into sharper focus the role of Islam in Senegal. -

TIJANIYYAH in ILORIN, NIGERIA Abdur-Razzaq Mustapha Balogun

Ilorin Journal of Religious Studies, (IJOURELS) Vol.8 No.1, 2018, pp.63-78 AN EXAMINATION OF THE EMERGENCE OF FAYDAH AT- TIJANIYYAH IN ILORIN, NIGERIA Abdur-Razzaq Mustapha Balogun Solagberu Department of Islamic Studies Kwara State College of Arabic and Islamic Legal Studies, Ilorin P.M.B. 1579, Ilorin [email protected] [email protected] +2348034756380; +2348058759700 Abstract The work examines the history of Faydah at-Tijaniyyah (Divine Flood of the Tijaniyyah Order) in Ilorin. A spiritual transformation which the founder of the Tijaniyyah Sūfī Order, Shaykh Ahmad at-Tijani (d. 1815 C.E) prophecised Shaykh Ibrahim Niyass (d. 1975CE) proclaimed himself to be the person blessed with such position, and spread it across West Africa cities including Ilorin, Nigeria. The objective of this research it to fill the gap created in the history of Tijaniyyah Sūfī Order in Ilorin. The method of the research is based on both participatory observation and interpretative approach of relevant materials. The paper concludes that the advent of Faydah at-Tijaniyyah to Ilorin was due to many factors,and brought about a new understanding on the Tijaniyyah Order. Keywords: Tijaniyyah, Sūfī, Tariqah, Khalifah, Faydah at-Tijaniyyah Introduction Shaykh Ahmad at-Tijani, the founder of the Tijaniyyah Sūfī Order predicted that Divine flood would occur on his Sūfī disciples when people would be joining his Sūfī Order in multiple1. The implication is that, at a certain period of time, someone among the Tijaniyyah members would emerge as Sahib al- Faydah (the Flag-bearer of the divine flood). Through him, people of multifarious backgrounds would be embracing the Tijaniyyah Order. -

The Rural Electrification Senegal (ERSEN) Project: Electricity for Over 90,000 Persons

Each day, children from villages having benefit- Information and communication are made easier ted from ERSEN project interventions study 30 Thanks to rural electrification, one can witness the emergence of minutes longer on average than children with no new habits with regards to accessing information (TV, Radio). access to electricity. (RWI impact study, 2011) In all the electrified villages, the population seems to be very satis- fied with their access to TV, or not having to travel to town to charge their mobile phone. In Ndiaye Kahone (Kaolack re- gion), village inhabitants now use new technologies and the village youths surf the internet with their computers. School results improve Teachers and students alike also benefit from access to electricity. Children can do their homework in the evening in much better condi- tions and benefit from the teach- The Rural Electrification Senegal (ERSEN) Project: ers’ use of new teaching supports that would otherwise not be avail- Electricity for over 90,000 persons. able. Background The quality of medical services improves The local economy is boosted In 2010, over 80% of rural Senegalese households still had no uses renewable energy (solar and wind power) to provide electric- access to electricity. In a great number of communities, schools ity to remote areas that cannot be immediately or easily connected Certain services, such childbirth at night, can now be provided in Thanks to solar mills, sewing workshops, carpentry and metalwork and health posts deliver their services without any electricity. The to the existing distribution grid. much better conditions. The small health post in Ndiaye Kahone businesses, the communities are also witnessing a new boost in Government of Senegal has therefore set itself the challenge of thus benefits from access to electricity: Faama Diop, the midwife income-generating activities. -

Site Visit of the Energy Project ... the GAMBIA ... Where Are

Kaolack KAFFRINE Birkilane L1b L1a Koungheul L3a Kedougou (Senegal) - Mali (Guinea) L6b Tambacoundaa KAOLACK D1 TAMBACOUNDA A single-circuit line 59 km long, supported Site visit of GAMBIA RIVER BASIN DEVELOPMENT THE GAMBIA ORGANISAbyTION 152 triangular towers. 26 km are in the KANIFING CENTRAL RIVER ORGANISATION POUR LA MISE EN VALEUR DU FLEUVE GASenegaleseMBIE territory and 33 km in Guinea. No UPPER RIVER L2 the Energy Project ... Energy Project Brikama Soma WEST COASTT L7 SENEGAL construction activities have yet started on L6a this section because of problems related to SEDHIOU KOLDA the bypass of the "Bassari country", which is ZIGUINCHOR ... where are we? KEDOUGOU OMVG Tana a UNESCO-protected site, measures aimed at LD1 protecting areas identified as natural habitats for Sambangalou L5d ORGANISATION OOIO GUINEABISSAU chimpanzees, change to the delineation due to rior to our visit to the work sites in The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea and BAFATA POUR LA MISE EN VALEUR L3a the substation site relocation from Sambangalou Senegal, it should be mentioned that OMVG’s new transformer substations Mansoaoa GABU P BBambadinca DU FLEUVE GAMBIE CACHEU L5c L5e Mali to Kedougou, etc.). - Projet Energie - are built on surfaces measuring between 2 and 15 ha, all fully free of Bissau L5b environmental burdens and constraints. Accommodation for future operating Saltinho L3b Tanaff (Senegal) - Soma (The Gambia) GAMBIA RIVER BASIN P1b Tambacounda and Kedougou substations L6aLABE and on-site maintenance staff is under construction at all substations GUINEA DEVELOPMENT (Sambangalou) A single-circuit line 95.22 km long, supported by 205 throughout the OMVG loop. Labé ORGANISATION TOMBALI BOKE triangular towers. -

Dakar, Senegal

DAKAR, SENEGAL Arrive: 0800 Saturday, October 31 Onboard: 1800 Tuesday, November 3 Brief Overview: French-speaking Dakar, Senegal is the western-most city in all of Africa. The capital and largest city in Senegal, Dakar is located on the Cape Verde peninsula on the Atlantic. Dakar has maintained remnants of its French colonial past, and has much to offer both geographically and culturally. Travel north to the city of Saint Louis and see the Djoudj National Bird sanctuary, home to more than 1.5 million exotic birds, including 30 different species that have made their way south from Europe. Take a trip south from Dakar to the Delta de Saloum and enjoy the rich vegetation and water activities, like kayaking on the Gambie River. Visit the Pink Lake to see and learn from local salt harvesters. Discover the history of the Dakar slave trade with a visit to Goree Island, one of the major slave trading posts from the mid 1500s to the mid 1800s, where millions of enslaved men, women and children made their way through the “door of no return.” Touba, a city just a few hours inland from Dakar, is home to Africa’s second-largest mosque. Don’t leave Senegal without exploring one of the many outdoor markets with local crafts and traditional jewelry made by the native Fulani Senegalese tribe. Highlights: Cultural Highlights: Art and Architecture: Day 1: DAK 401-101 Casamance & Mandigo Country Day 2: DAK 105-201 Art Workshop Day 1: DAK 101-101 Goree Island Day 3: DAK 108-301 Art Tour with Lunch Day 1: DAK 103-103 Welcome Reception Nature & the Outdoors: Day 2: 201-201 La Petite Cote & Senegalese Naming Day 2: DAK 302-201 Toubacouta & Saloum Delta Ceremony Day 2: DAK 303-201 Nikolo Park & Eastern Senegal Day 2: DAK 107-301 Holy City of Touba & Thies Market Day 2: DAK 102-201 Bandia Reserve & Saly TERMS AND CONDITIONS: In selling tickets or making arrangements for field programs (including transportation, shore-side accommodations and meals), the Institute acts only as an agent for other entities who provide such services as independent contractors. -

K a O L a C K 2 0

REPUBLIQUE DU SENEGAL Un Peuple – Un But – Une Foi ------------------ K MINISTERE DE L’ECONOMIE, DES FINANCES ET DU PLAN ------------------ AGENCE NATIONALE DE LA STATISTIQUE A ET DE LA DEMOGRAPHIE ------------------ O Service Régional de la Statistique et de la Démographie de Kaolack L A C K 2 SITUATION ECONOMIQUE ET 0 SOCIALE REGIONALE 2013 1 Avril 2015 3 ANSD/SRSD Kaolack : Situation Economique et Sociale régionale ‐ 2013 ii RESUME EXECUTIF Situation géographique, administrative et démographique de la région La région de Kaolack est localisée entre 14°30 mn et 16°30 mn de longitude ouest et 13°30 mn et 14°30 mn de latitude nord. Elle s’étend sur une superficie de 5 357 km2, soit environ 2,8% du territoire national. Elle se situe ainsi entre la zone sahélienne sud et la zone soudanienne nord en constituant avec les régions de Kaffrine, Fatick et Diourbel le cœur du bassin arachidier Le climat est de type soudano-sahélien avec des températures élevées d’avril à juillet (35°- 40°c) Le relief est essentiellement plat avec trois types de sols : les sols tropicaux ferrugineux lessivés, les sols hydromorphes et les sols halomorphes. La végétation est très variée et comprend une savane arbustive au nord et une savane plus ou moins boisée vers le sud et le sud-est. La faune est essentiellement composée d’animaux sauvages à poils et à plumes aquatiques et terrestres. Le réseau hydrographique est composé du bras de mer le Saloum et des affluents du fleuve Gambie (Baobolong et Miniminiyang Bolong) Avec le nouveau découpage, la région de Kaolack compte: 3 départements, 10 communes, 8 arrondissements et 31 communautés rurales .Situation démographique D’après le dernier recensement général de la population, de l’Habitat, de l’Agriculture et de l’Elevage (RGPHAE 2013) la région de Kaolack compte 960 875 habitants avec 50,6 % de femmes contre 49,4% d’hommes. -

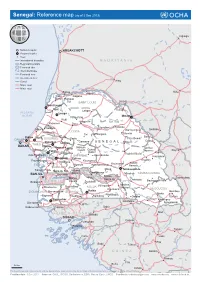

M a U R I T a N I a G U I N E a M a L I Guinea-Bissau Gambia

Senegal: Reference map (as of 3 Dec 2013) Tidjikdja National capital NOUAKCHOTT Regional capital Town International boundary MAURITANIA Regional boundary Perennial lake Intermittent lake Perennial river Intermittent river Canal Aleg Major road Minor road Sénégal Rosso Kiffa Podor Ross Dagana Béthio Richard Toll SAINT LOUIS Kaédi Saint Louis Mpal Labgar Thilogne ATLANTIC Louga OCEAN Matam Yang-Yang Koki Linguère MATAM Kébémèr Dara Ndande Yonoféré Ranérou Mboro Diamounguél Sélibaby Mékhé LOUGA Tiel Vélingara Mamâri Bakel Pikine Thies Touba DAKAR DIOURBEL Sadio Fété Bowé Gassane Gabou Sé Diourbel SENEGAL Mboun négal THIÈS Mbacké DAKAR Niakhar Gossas Mbar Ndioum Sintiou Mbour Guènt Guènt Tapsirou Kayes Fatick Paté Guinguinéo Toubéré Bafal Kidira Joal-Fadhiouth KAFFRINE Lour-Escale Koussane Kaolack Kaffrine Goudiry Foundiougne Ndoffane Koungheul Sokone Koussanar Kotiari FATICK Nganda Koumpentoum Naoude MALI KAOLACK Gambi Maka Tambacounda Karang Poste Nioro du Rip Médina a Sabakh Georgetown TAMBACOUNDA BANJUL Kerewan Missirah Basse Mansa Pata Saïnsoubou Santa Su Dialacoto Boutougou Fara Brikama GAMBIA Konko Soulabali Vélingara Medina Diouloulou Bounkiling KOLDA Gounas Kounkané KÉDOUGOU ZIGUINCHOR Marsassoum SÉDHIOU Kolda Bembou Wassadou Mako Bignona Sédhiou Salikénié Dalaba Saraya Ziguinchor Tiankoye Kédougou Koundara Fongolembi Diembéreng Farim Kabrousse Cacheu Gabú a b Mali GUINEA-BISSAU ê Bafadá G BISSAU Gaoual Fulacunda ia b Bolama m G a Tongué a Catió Labé g n i f a Pita B Boké Telimele GUINEA Dalaba Mamou Fria Boffa 50 Km Kindia The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. Creation date: 3 Dec 2013 Sources: GAUL, ISCGM, Bartholomew, ESRI, Natural Earth, UNCS Feedback: [email protected] www.unocha.org www.reliefweb.int.