9781469660844.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past, Present, and Future FIFTY YEARS of ANTHROPOLOGY in SUDAN

Past, present, and future FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN Munzoul A. M. Assal Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil Past, present, and future FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN Munzoul A. M. Assal Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil FIFTY YEARS OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN SUDAN: PAST, PRESENT, AND FUTURE Copyright © Chr. Michelsen Institute 2015. P.O. Box 6033 N-5892 Bergen Norway [email protected] Printed at Kai Hansen Trykkeri Kristiansand AS, Norway Cover photo: Liv Tønnessen Layout and design: Geir Årdal ISBN 978-82-8062-521-2 Contents Table of contents .............................................................................iii Notes on contributors ....................................................................vii Acknowledgements ...................................................................... xiii Preface ............................................................................................xv Chapter 1: Introduction Munzoul A. M. Assal and Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil ......................... 1 Chapter 2: The state of anthropology in the Sudan Abdel Ghaffar M. Ahmed .................................................................21 Chapter 3: Rethinking ethnicity: from Darfur to China and back—small events, big contexts Gunnar Haaland ........................................................................... 37 Chapter 4: Strategic movement: a key theme in Sudan anthropology Wendy James ................................................................................ 55 Chapter 5: Urbanisation and social change in the Sudan Fahima Zahir El-Sadaty ................................................................ -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

The Question of 'Race' in the Pre-Colonial Southern Sahara

The Question of ‘Race’ in the Pre-colonial Southern Sahara BRUCE S. HALL One of the principle issues that divide people in the southern margins of the Sahara Desert is the issue of ‘race.’ Each of the countries that share this region, from Mauritania to Sudan, has experienced civil violence with racial overtones since achieving independence from colonial rule in the 1950s and 1960s. Today’s crisis in Western Sudan is only the latest example. However, very little academic attention has been paid to the issue of ‘race’ in the region, in large part because southern Saharan racial discourses do not correspond directly to the idea of ‘race’ in the West. For the outsider, local racial distinctions are often difficult to discern because somatic difference is not the only, and certainly not the most important, basis for racial identities. In this article, I focus on the development of pre-colonial ideas about ‘race’ in the Hodh, Azawad, and Niger Bend, which today are in Northern Mali and Western Mauritania. The article examines the evolving relationship between North and West Africans along this Sahelian borderland using the writings of Arab travellers, local chroniclers, as well as several specific documents that address the issue of the legitimacy of enslavement of different West African groups. Using primarily the Arabic writings of the Kunta, a politically ascendant Arab group in the area, the paper explores the extent to which discourses of ‘race’ served growing nomadic power. My argument is that during the nineteenth century, honorable lineages and genealogies came to play an increasingly important role as ideological buttresses to struggles for power amongst nomadic groups and in legitimising domination over sedentary communities. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

Falsafah ,Sains,Dan Pemikiran Islam.Pdf

SEMINAR PEMIKIRAN ISLAM III Sudut Pandangan Islam Dalam Diskusi Sesama Muslim FALSAFAH, SAINS DAN PENDIDIKAN ISLAM JABATAN AKIDAH DAN PEMIKIRAN ISLAM AKADEMI PENGAJIAN ISLAM UNIVERSITI MALAYA 2012 ISI KANDUNGAN ARABIC-ISLAMIC CULTURE: THE CLASSIFICATION OF THE SCIENCES IN THE MEDIEVAL PERIOD AND ITS INFLUENCE ON THE CONTEMPORARY SCHOLARSHIP .................................................................1 Animashaun, Maruf Suraqat TABATABAIE'S CONTROVERSIAL IDEAS IN ISLAMIC MORAL THOUGHT; A LESSON LEARNED FOR EDUCATIONAL PROSPERITY OF ISLAMIC ACADEMIES ................................................................... 11 Soroush Dabbagh and Hossein Dabbagh YAHYA IBN ‘ADI ON HAPPINESS ................................................................................................... 17 Mohd Nasir Omar THE DEBATE OVER RATIONAL AND TRADITIONAL PROOFS IN ISLAM: A RECONCILIATORY APPROACH .................................................................................................................................. 25 Mohd Farid Mohd Shahran BALANCING THE CONTEMPORARY APPROACH TO THINKING: APPLYING THE GHAZZĀLIAN FRAMEWORK .............................................................................................................................. 33 Mohd Zaidi b. Ismail WASIYYAH ABI HANIFAH LI ABI YUSUF: SUATU PENGENALAN DAN SUNTINGAN ILMIAH ............... 39 Mohd Anuar Mamat METODOLOGI PENGAJARAN DAN PEMBELAJARAN MENURUT IBN KHALDUN DAN JOHN DEWEY: KAJIAN PERBANDINGAN ............................................................................................................. -

Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Studying Jihadism 2 3 4 5 6 Volume 2 7 8 9 10 11 Edited by Rüdiger Lohlker 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 The volumes of this series are peer-reviewed. 37 38 Editorial Board: Farhad Khosrokhavar (Paris), Hans Kippenberg 39 (Erfurt), Alex P. Schmid (Vienna), Roberto Tottoli (Naples) 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 Rüdiger Lohlker (ed.) 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jihadism: Online Discourses and 8 9 Representations 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 With many figures 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 & 37 V R unipress 38 39 Vienna University Press 40 41 Open-Access-Publikation im Sinne der CC-Lizenz BY-NC-ND 4.0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; 24 detailed bibliographic data are available online: http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

The Layha for the Mujahideen: an Analysis of the Code of Conduct for the Taliban Fighters Under Islamic Law

Volume 93 Number 881 March 2011 The Layha for the Mujahideen:an analysis of the code of conduct for the Taliban fighters under Islamic law Muhammad Munir* Dr.Muhammad Munir is Associate Professor and Chairman,Department of Law, Faculty of Shari‘a and Law, International Islamic University, Islamabad. Abstract The following article focuses on the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan Rules for the Mujahideen** to determine their conformity with the Islamic jus in bello. This code of conduct, or Layha, for Taliban fighters highlights limiting suicide attacks, avoiding civilian casualties, and winning the battle for the hearts and minds of the local civilian population. However, it has altered rules or created new ones for punishing captives that have not previously been used in Islamic military and legal history. Other rules disregard the principle of distinction between combatants and civilians and even allow perfidy, which is strictly prohibited in both Islamic law and international humanitarian law. The author argues that many of the Taliban rules have only a limited basis in, or are wrongly attributed to, Islamic law. * The help of Andrew Bartles-Smith, Prof. Brady Coleman, Major Nasir Jalil (retired), Ahmad Khalid, and Dr. Marty Khan is acknowledged. The quotations from the Qur’an in this work are taken, unless otherwise indicated, from the English translation by Muhammad Asad, The Message of the Qur’an, Dar Al-Andalus, Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wiltshire, 1984, reprinted 1997. ** The full text of the Layha is reproduced as an annex at the end of this article. doi:10.1017/S1816383111000075 81 M. Munir – The Layha for the Mujahideen: an analysis of the code of conduct for the Taliban fighters under Islamic law Do the Taliban qualify as a ‘non-state armed group’? Since this article deals with the Layha,1 it is important to know whether the Taliban in Afghanistan, as a fighting group, qualify as a ‘non-state Islamic actor’. -

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center Is Launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal

The Integrated Economic and Social Development Center is launched in the Kaolack Region of Senegal On February 27, 2015 the General Assembly for the formal establishment of the Integrated Economic and Social Development Center – CIDES Saloum of Kaolack’ Region was held within the premises of Kaolack’s Departmental Council. The event was chaired by the Minister of Women, Family and Child, by the Regional Governor and by the Mayors of the Department of Kaolack, Guinguinéo and Nioro. Amongst the participants were also the local authorities, senior representatives of the administrations and territorial services, representatives of undergoing programs, the Coordinator of the Ministry of Woman Unit for Poverty Reduction and representatives of the Italian Cooperation, plus all members of the CIDES Saloum. After opening words of the President of the Departmental Council of Kaolack, the Minister of Women on behalf of the President of the Republic recognized the efforts of all participants and the Government of Italy to support Senegal developmental policies. The Minister marked how CIDES represents a strategic tool for the development of territories and how it organically sets in the guidelines of Act III of the national decentralization policies. The event was led by a series of presentations and discussions on the results of the CIDES Saloum participatory design process, submission and approval of the Statute and the final election of members of its management structure. This event represents the successful completion of an action-research process developed over a year to design, through the active participation of local actors, the mission, strategic objectives and functions of Kaolack’s Integrated Center for Economic and Social Development. -

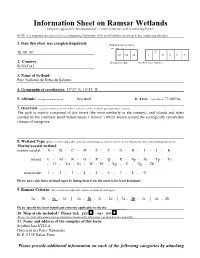

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. NOTE: It is important that you read the accompanying Explanatory Note and Guidelines document before completing this form. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY 18. 08. 92 S 03 04 84 1 E 0 0 3 2. Country: Designation date Site Reference Number SENEGAL 3. Name of wetland: Parc National du Delta du Saloum 4. Geographical coordinates: 13°37’ N, 16°42’ W 5. Altitude: (average and/or max. & min.) Sea level 6. Area: (in hectares) 73,000 ha 7. Overview: (general summary, in two or three sentences, of the wetland's principal characteristics) The park is mainly composed of dry forest (the most northerly in the country), and islands and islets created by the countless small watercourses (“bolons”) which weave around the ecologically remarkable clumps of mangrove. 8. Wetland Type (please circle the applicable codes for wetland types as listed in Annex I of the Explanatory Note and Guidelines document.) Marine/coastal wetland marine-coastal: A • B • C • D • E • F • G • H • I • J • K inland: L • M • N • O • P • Q • R • Sp • Ss • Tp • Ts • U • Va • Vt • W • Xf • Xp • Y • Zg • Zk man-made: 1 • 2 • 3 • 4 • 5 • 6 • 7 • 8 • 9 Please now rank these wetland types by listing them from the most to the least dominant: 9. Ramsar Criteria: (please circle the applicable criteria; see point 12, next page.) 1a • 1b • 1c • 1d │ 2a • 2b • 2c • 2d │ 3a • 3b • 3c │ 4a • 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: __________ 10. -

13 Lessons to Tajweed Comprehension Dr Abu Zayd Quran Literacy Institute a N Islamic Learning Foundation a F F I L I a T E

T h e A r t of T a j w e e d 13 Lessons to Tajweed Comprehension Dr Abu Zayd Quran Literacy Institute A n Islamic Learning Foundation A f f i l i a t e 2011 The Childrens Bequest LESSON ONE: ال يمىق ِّدىمة INTRODUCTION The Childrens Bequest The Prophet: إ َّن ِ ِلِل أهلٌِ َن ِم َن ال َّناس أَ ْهلُ القُرآ ِن ُه ْم أَ ْهلُ ِهللا َو َخا َّصـ ُت ُه [Musnad Ahmad] A h l al- Q u r a n The Childrens Bequest T h e S t o r y One Book One Man A Statement A Team A Divine Chain An Invitation The Childrens Bequest عن أَبي عَبِد الزََّحِنن عن عُثِنَانَ بنِ عَفََّانَ ، أَنََّ رَسُولُ اهلل قالَ: قالَ أَبُو عَبِد الزََّحِنن فَذَاكَ الََّذِي أَقِعَدَنِي مَقِعَدِي هَذَا، وَعَمّهَ الِقُزِآنَ فِي سمن عُثِنَانَ حَتََّى بَمَغَ الِخَجََّاجَ بنَ يُوسُفَ . al- T i r m i d h ī 2985 The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION ال يمىق ِّدىمة THE COURSE: A comprehensive review of the rules of Tajweed according to the Reading of Ḥafṣ based upon the text Tuhfah al-Aṭfāl by Sulaymān al-Jamzūrī. The Formal Rules Theory of Tajweed History Biographies of the Imāms of Recitation اﻹق َراء ’Practice Iqrā The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION المىق ِّدمة ي ى Advanced Topic ُتح َف ُة اﻷط َفال The Childrens Bequest The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION المىق ِّدمة ي ى PREREQUISITES • Ability to read Arabic script • Basic knowledge of Tajweed WHAT YOU NEED FOR THIS CLASS • Writing material • Mushaf (preferably Madinan edition) • Voice Recorder (optional) • POSITIVE ATTITUDE The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION المىق ِّدمة ي ى Benefits of the Class Will improve your pronunciation and recitation of the Qur’an. -

CA Students Urge Assembly Members to Pass AB

May 26, 2021 The Honorable Members of the California State Assembly State Capitol Sacramento, CA 95814 RE: Thousands of CA Public School Students Strongly Urge Support for AB 101 Dear Members of the Assembly, We are a coalition of California high school and college students known as Teach Our History California. Made up of the youth organizations Diversify Our Narrative and GENup, we represent 10,000 youth leaders from across the State fighting for change. Our mission is to ensure that students across California high schools have meaningful opportunities to engage with the vast, diverse, and rich histories of people of color; and thus, we are in deep support of AB101 which will require high schools to provide ethnic studies starting in academic year 2025-26 and students to take at least one semester of an A-G approved ethnic studies course to graduate starting in 2029-30. Our original petition made in support of AB331, linked here, was signed by over 26,000 CA students and adult allies in support of passing Ethnic Studies. Please see appended to this letter our letter in support of AB331, which lists the names of all our original petition supporters. We know AB101 has the capacity to have an immense positive impact on student education, but also on student lives as a whole. For many students, our communities continue to be systematically excluded from narratives presented to us in our classrooms. By passing AB101, we can change the precedent of exclusion and allow millions of students to learn the histories of their peoples. -

Sufism and Tariqas Facing the State: Their Influence on Politics in the Sudan

Sufism and Tariqas Facing the State Sufism and Tariqas Facing the State: Their Influence on Politics in the Sudan Daisuke MARUYAMA* This study focuses on the political influence of Sufism and tariqas in the Sudan. Previous studies have emphasized the political influences of Sufi shaykhs and tariqas on Sudan’s history and demonstrated why and how Sufis and tariqas have exercised their political influence over time; however, the problem is that these researches are largely limited to only two particular religious orders, the Khatmµya order and the An≠±r, that have their own political parties. Therefore, this study stresses on the political importance of Sufis and tariqas without their own political parties and aims to reveal their presence in present Sudanese politics, with special references to the strategies and activities of the government and the remarks of Sufis at meetings held by several tariqas during the national election campaign in 2010. In order to reveal the influences of Sufism and tariqas without their own political parties in Sudanese politics, this study introduces four sections. The first section traces the historical transition of the political influences of Sufism and tariqa from the rudiment until the present Islamist government. The second section introduces the thoughts of Islamists toward Sufism in the Islamic Movement (al-≈araka al-Isl±mµya) such as the introduction of new terminology ahl al-dhikr (people that remember [All±h]), which accentuates the political attitude toward Sufism, and the third section deals with the policies and activities of the present government with regard to Sufism and tariqas, such as the foundation of the committee for Sufis and tariqas.