Jihadism: Online Discourses and Representations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ISIS Propaganda and United States Countermeasures

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Fall 2015 ISIS Propaganda and United States Countermeasures Daniel Lincoln Stevens As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons Recommended Citation Stevens, Daniel Lincoln, "ISIS Propaganda and United States Countermeasures" (2015). MSU Graduate Theses. 1503. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/1503 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISIS PROPAGANDA AND UNITED STATES COUNTERMEASURES A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science, Defense and Strategic Studies By Daniel Stevens December 2015 Copyright 2015 by Daniel Lincoln Stevens ii ISIS PROPAGANDA AND UNITED STATES COUNTERMEASURES Defense and Strategic studies Missouri State University, December 2015 Master of Science Daniel Stevens ABSTRACT The purpose of this study is threefold: 1. Examine the use of propaganda by the Islamic State in Iraq and al Sham (ISIS) and how its propaganda enables ISIS to achieve its objectives; 2. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

The Struggle Against Musaylima and the Conquest of Yamama

THE STRUGGLE AGAINST MUSAYLIMA AND THE CONQUEST OF YAMAMA M. J. Kister The Hebrew University of Jerusalem The study of the life of Musaylima, the "false prophet," his relations with the Prophet Muhammad and his efforts to gain Muhammad's ap- proval for his prophetic mission are dealt with extensively in the Islamic sources. We find numerous reports about Musaylima in the Qur'anic commentaries, in the literature of hadith, in the books of adab and in the historiography of Islam. In these sources we find not only material about Musaylima's life and activities; we are also able to gain insight into the the Prophet's attitude toward Musaylima and into his tactics in the struggle against him. Furthermore, we can glean from this mate- rial information about Muhammad's efforts to spread Islam in territories adjacent to Medina and to establish Muslim communities in the eastern regions of the Arabian peninsula. It was the Prophet's policy to allow people from the various regions of the peninsula to enter Medina. Thus, the people of Yamama who were exposed to the speeches of Musaylima, could also become acquainted with the teachings of Muhammad and were given the opportunity to study the Qur'an. The missionary efforts of the Prophet and of his com- panions were often crowned with success: many inhabitants of Yamama embraced Islam, returned to their homeland and engaged in spreading Is- lam. Furthermore, the Prophet thoughtfully sent emissaries to the small Muslim communities in Yamama in order to teach the new believers the principles of Islam, to strengthen their ties with Medina and to collect the zakat. -

Urgensi Ijtihad Saintifik Dalam Menjawab Problematika Hukum Transaksi Kontemporer

Volume 4, Nomor 2, Desember 2011 URGENSI IJTIHAD SAINTIFIK DALAM MENJAWAB PROBLEMATIKA HUKUM TRANSAKSI KONTEMPORER Oleh : Fauzi M Abstract: This article will discuss abaout the rational urgency to do scientific ijtihad to answer the legal issues of contemporary transaction and also perform scientific ijtihad basis and examples of scientific ijtihad in answering legal issues of contemporary transactions. Key words: rational urgency, scientific ijtihad, contemporary transaction. Pendahuluan Era globalisasi (the age of globalization), dalam beberapa literatur dinyatakan bermula pada dekade 1990‐an.1 Era ini ditandai, diantaranya dengan adanya fenomena penting dalam bidang ekonomi. Kegiatan ekonomi dunia tidak hanya dibatasi oleh faktor batas geografi, bahasa, budaya dan ideologi, akan tetapi lebih karena faktor saling membutuh‐kan dan saling bergantung satu sama lain.2 Dunia menjadi seakan‐akan tidak ada batas, terutama karena perkembangan teknologi informasi yang begitu pesat. Keadaan yang 1 Globalization is accepted as one of the fundamental of the processes that characterize the contemporary world, a process leading towards an increasingly strong interdependence between increasingly large parts of the world. S. Parvez Manzoor (2004), “Book Review ‘Islam in the Era of Globalization: Muslim Attitudes Towards Modernity and Identity” oleh Johan Meuleman (ed.) (2002), London: RoutledgeCurzon, dimuat dalam Journal of Islamic Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2, Mei 2004, Oxford: Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, h. 280. 2 Jan Pronk (2001), “Globalization: A Developmental Approach”, dalam Jan Nederveen Pieterse (ed.), Global Futures, Shaping Globalization, London: Zed Books, h. 43. 20 Fauzi M, Urgensi Ijtihad ... demikian melahirkan banyak peluang sekaligus tantangan,3 terutamanya dalam hal transaksi (muamalah) kepa‐da semua pihak, termasuk umat Islam.4 Proses globalisasi diperkirakan semakin bertambah cepat pada masa mendatang, sebagaimana dikemukakan oleh Colin Rose bahwa dunia sedang berubah dengan kecepatan langkah yang belum pernah terjadi sebelumnya. -

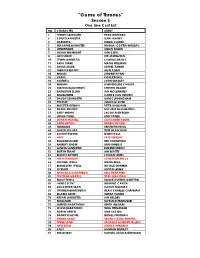

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO

“Game of Thrones” Season 5 One Line Cast List NO. CHARACTER ARTIST 1 TYRION LANNISTER PETER DINKLAGE 3 CERSEI LANNISTER LENA HEADEY 4 DAENERYS EMILIA CLARKE 5 SER JAIME LANNISTER NIKOLAJ COSTER-WALDAU 6 LITTLEFINGER AIDAN GILLEN 7 JORAH MORMONT IAIN GLEN 8 JON SNOW KIT HARINGTON 10 TYWIN LANNISTER CHARLES DANCE 11 ARYA STARK MAISIE WILLIAMS 13 SANSA STARK SOPHIE TURNER 15 THEON GREYJOY ALFIE ALLEN 16 BRONN JEROME FLYNN 18 VARYS CONLETH HILL 19 SAMWELL JOHN BRADLEY 20 BRIENNE GWENDOLINE CHRISTIE 22 STANNIS BARATHEON STEPHEN DILLANE 23 BARRISTAN SELMY IAN MCELHINNEY 24 MELISANDRE CARICE VAN HOUTEN 25 DAVOS SEAWORTH LIAM CUNNINGHAM 32 PYCELLE JULIAN GLOVER 33 MAESTER AEMON PETER VAUGHAN 36 ROOSE BOLTON MICHAEL McELHATTON 37 GREY WORM JACOB ANDERSON 41 LORAS TYRELL FINN JONES 42 DORAN MARTELL ALEXANDER SIDDIG 43 AREO HOTAH DEOBIA OPAREI 44 TORMUND KRISTOFER HIVJU 45 JAQEN H’GHAR TOM WLASCHIHA 46 ALLISER THORNE OWEN TEALE 47 WAIF FAYE MARSAY 48 DOLOROUS EDD BEN CROMPTON 50 RAMSAY SNOW IWAN RHEON 51 LANCEL LANNISTER EUGENE SIMON 52 MERYN TRANT IAN BEATTIE 53 MANCE RAYDER CIARAN HINDS 54 HIGH SPARROW JONATHAN PRYCE 56 OLENNA TYRELL DIANA RIGG 57 MARGAERY TYRELL NATALIE DORMER 59 QYBURN ANTON LESSER 60 MYRCELLA BARATHEON NELL TIGER FREE 61 TRYSTANE MARTELL TOBY SEBASTIAN 64 MACE TYRELL ROGER ASHTON-GRIFFITHS 65 JANOS SLYNT DOMINIC CARTER 66 SALLADHOR SAAN LUCIAN MSAMATI 67 TOMMEN BARATHEON DEAN-CHARLES CHAPMAN 68 ELLARIA SAND INDIRA VARMA 70 KEVAN LANNISTER IAN GELDER 71 MISSANDEI NATHALIE EMMANUEL 72 SHIREEN BARATHEON KERRY INGRAM 73 SELYSE -

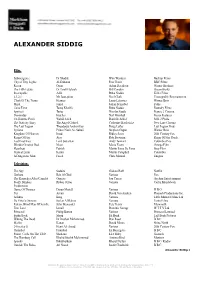

Alexander Siddig

ALEXANDER SIDDIG Film: Submergence Dr Shadid Wim Wenders Backup Films City of Tiny Lights Al-Dabaran Pete Travis BBC Films Recon Omar Adam Davidson Warner Brothers The Fifth Estate Dr Tarek Haliseh Bill Condon DreamWorks Inescapable Adib Ruba Nadda Killer Films 4.3.2.1 Mr Jauo-pinto Noel Clark Unstoppable Entertainment Clash Of The Titans Hermes Louis Leterrier Warner Bros Miral Jamal Julian Schnabel Pathe Cairo Time Tareq Khalifa Ruba Nadda Foundry Films Spy(ies) Tariq Nicolas Saada France 2 Cinema Doomsday Hatcher Neil Marshall Focus Features Un Homme Perdi Wahid Saleh Danielle Arbid M K 2 Prods. The Nativity Story The Angel Gabriel Catherine Hardwicke New Line Cinema The Last Legion Theodorus Andronikos Doug Lefler Last Legion Prod Syriana Prince Nasir Al- Subaii Stephen Gagan Warner Bros Kingdom Of Heaven Imad Ridley Scott 20th Century Fox Reign Of Fire Ajay Rob Bowman Reign Of Fire Prods. Last First Kiss Lord Sebastian Andy Tennant Columbia Pics World's Greatest Dad Nisse Maria Essen Omega Film Heartbeat Patrick Martin Lima De Faria Stop Film Vertical Limit Karim Martin Campbell Columbia A Dangerous Man Faisal Chris Menaul Enigma Television: The Spy Sudaini Gideon Raff Netflix Gotham Ra's Al Ghul Various Fox The Kennedys After Camelot Onassis Jon Cassar Asylum Entertainment Peaky Blinders Ruben Oliver Various Caryn Mandabach Productions Game Of Thrones Doran Martell Various H B O Tut Amun David Von Ancken Pharaoh Productions Inc. Atlantis King Various Little Monster Films Ltd Da Vinci's Demons Saslan Al Rahim Various Tonto Films Falcon; -

13 Lessons to Tajweed Comprehension Dr Abu Zayd Quran Literacy Institute a N Islamic Learning Foundation a F F I L I a T E

T h e A r t of T a j w e e d 13 Lessons to Tajweed Comprehension Dr Abu Zayd Quran Literacy Institute A n Islamic Learning Foundation A f f i l i a t e 2011 The Childrens Bequest LESSON ONE: ال يمىق ِّدىمة INTRODUCTION The Childrens Bequest The Prophet: إ َّن ِ ِلِل أهلٌِ َن ِم َن ال َّناس أَ ْهلُ القُرآ ِن ُه ْم أَ ْهلُ ِهللا َو َخا َّصـ ُت ُه [Musnad Ahmad] A h l al- Q u r a n The Childrens Bequest T h e S t o r y One Book One Man A Statement A Team A Divine Chain An Invitation The Childrens Bequest عن أَبي عَبِد الزََّحِنن عن عُثِنَانَ بنِ عَفََّانَ ، أَنََّ رَسُولُ اهلل قالَ: قالَ أَبُو عَبِد الزََّحِنن فَذَاكَ الََّذِي أَقِعَدَنِي مَقِعَدِي هَذَا، وَعَمّهَ الِقُزِآنَ فِي سمن عُثِنَانَ حَتََّى بَمَغَ الِخَجََّاجَ بنَ يُوسُفَ . al- T i r m i d h ī 2985 The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION ال يمىق ِّدىمة THE COURSE: A comprehensive review of the rules of Tajweed according to the Reading of Ḥafṣ based upon the text Tuhfah al-Aṭfāl by Sulaymān al-Jamzūrī. The Formal Rules Theory of Tajweed History Biographies of the Imāms of Recitation اﻹق َراء ’Practice Iqrā The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION المىق ِّدمة ي ى Advanced Topic ُتح َف ُة اﻷط َفال The Childrens Bequest The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION المىق ِّدمة ي ى PREREQUISITES • Ability to read Arabic script • Basic knowledge of Tajweed WHAT YOU NEED FOR THIS CLASS • Writing material • Mushaf (preferably Madinan edition) • Voice Recorder (optional) • POSITIVE ATTITUDE The Childrens Bequest INTRODUCTION المىق ِّدمة ي ى Benefits of the Class Will improve your pronunciation and recitation of the Qur’an. -

Eugenie Pastor-Phd Thesis Moving Intimacies

MOVING INTIMACIES: A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF “PHYSICAL THEATRES” IN FRANCE AND THE UNITED KINGDOM EUGÉNIE FLEUR PASTOR ROYAL HOLLOWAY, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEPARTMENT OF DRAMA AND THEATRE A Thesis submitted as a partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Ph.D. August 2014 1 DECLARATION OF AUTHORSHIP I, Eugénie Fleur Pastor, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed: ______________________ Date: 7 August 2014 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is an exploration of movement in contemporary “physical theatres”. I develop a renewed understanding of “physical theatres” as embodied framework to experience both spectatorship and theatre-making. I analyse how, in this type of performance, movement blurs distinctions between the intimate and the collective, the inside and the outside, thus challenging definitions of intimacy and tactility. The thesis consists of a comparative study of examples of “physical theatres”, in the 21st century, in France and in the UK. The comparison highlights that “physical theatres” practitioners are under-represented in France, a reason I attribute in part to a terminological absence in the French language. The four case studies range from itinerant company Escale and their athletic embodiment of a political ideal to Jean Lambert-wild’s theatre of “micro-movement”, from Told by an Idiot’s position in a traditional theatre context in the UK to my own work within Little Bulb Theatre, where physicality is virtuosic in its non- virtuosity. For each case study, I use a methodology that echoes this exploration of movement and reflects my position within each fieldwork. -

Combating Al Qaeda and the Militant Islamic Threat TESTIMONY

TESTIMONY Combating Al Qaeda and the Militant Islamic Threat BRUCE HOFFMAN CT-255 February 2006 Testimony presented to the House Armed Services Committee, Subcommittee on Terrorism, Unconventional Threats and Capabilities on February 16, 2006 This product is part of the RAND Corporation testimony series. RAND testimonies record testimony presented by RAND associates to federal, state, or local legislative committees; government-appointed commissions and panels; and private review and oversight bodies. The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research organization providing objective analysis and effective solutions that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors around the world. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. is a registered trademark. Published 2006 by the RAND Corporation 1776 Main Street, P.O. Box 2138, Santa Monica, CA 90407-2138 1200 South Hayes Street, Arlington, VA 22202-5050 201 North Craig Street, Suite 202, Pittsburgh, PA 15213-1516 RAND URL: http://www.rand.org/ To order RAND documents or to obtain additional information, contact Distribution Services: Telephone: (310) 451-7002; Fax: (310) 451-6915; Email: [email protected] Dr. Bruce Hoffman1 The RAND Corporation Before the Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Terrorism, Unconventional Threats and Capabilities United States House of Representatives February 16, 2006 Four and a half years into the war on terrorism, the United States stands at a crossroads. The sustained successes of the war’s early phases appear to have been stymied by the protracted insurgency in Iraq and our inability either to kill or capture Usama bin Laden and his chief lieutenant, Ayman al-Zawahiri. -

Uwaylim Tajweed Text

SAFINA SOCIETY ِع ْل ُم ال ّت ْجوي ِد THE SCIENCE OF TAJWID Shadee Elmasry 2 َ َ َ ْ َ ّ ْ َ ْ ُ ْ َ ّ ْ َ َ ْ ّ ّ ولقد يسنا القرآن لِ ِلكرِ فهل ِمن مدكِ ٍر “We have made the Quran easy for remembrance, so is there anyone who will remember.” (54:17, 22, 32, 40). 3 CONTENTS PART ONE: BACKGROUND Chapter 1 Manners of the Heart 6 Chapter 2 The Science 8 Chapter 3 The Isti’adha & The Basmala 10 PART TWO: MAKHARIJ (Letter Pronunciation) Chapter 4 The Letters 11 Chapter 5 Letter Sets 15 A Hams B Qalqala C Tasfir D Isti’laa Chapter 6 Ahkaam al-Raa 17 A Tafkhim al-Raa B Tarqiq al-Raa i kasra below ii sukun and preceded by kasra iii sukun and preceded by another sukun then kasra PART THREE: THE RULES Chapter 7 Madd (vowel extension) 18 A Tabi’i (basic) B Muttasil (connected) C Munfasil (disconnected) D Lazim (prolonged) E Lin (dipthong) F ‘Arid lil-Sukun (pausing at the end of a verse) G Sila (connection) i kubra (major) ii sughra (minor) Chapter 8 Nun Sakina & Tanwin 22 A Idgham (assimilation) i with ghunna ii without ghunna B Iqlab (transformation) 4 C Izhar (manifestation) D Ikhfa (disappearance) Chapter 9 Idhgham of Consonants 24 A Mutamathilayn (identical) B Mutajanisayn (same origin) C Mutaqaribayn (similar) 5 Part One: Background CHAPTER ONE Manners of the Heart It is very important when reciting Quran to remember that these are not the words of a human being. -

The Enchantress of Florence

6620_enchantressofflorence_LIBV2_LayoutRBoverlay1_Layout 1 5/12/10 1:32 PM Page 1 4/2/101 2:28 PM Page 1 Salman Rushdie THE ENCHANTRESS OF FLORENCE Narrated by Firdous Bamji Few writers living or dead have received the monumental acclaim that has been accorded to Salman Rushdie for his richly textured, superbly crafted works. T The Enchantress of Florence once again demonstrates the author’s unparalleled mastery of H his craft. E In the imperial capital of the Mughal Empire, a traveler arrives at the court of E N Emperor Akbar. The traveler, Mogor dell’Amore, has a tale to tell, and as the words flow N a C out of him, the tale’s rich tapestry of power and desire begins to take on a life of its own. r S H r a Fueled by the urgency of his narrative and its growing effect on his audience, the traveler a A t l e paints a vivid portrait of faraway Florence, a beautiful enchantress, and the infamous m N d figure of Niccolò Machiavelli. T a b n y R Winner of the Booker Prize, Rushdie delights all those who revel in literature of F E R sublime achievement. Narrator Firdous Bamji matches the author’s exquisite prose with a i S r u d reading that conveys the full breadth of this lovingly detailed novel. S s o O h Narrator Firdous Bamji has appeared in numerous plays in New York and across the u s d F country and played the title role in William Shakespeare’s Othello . -

Here in the United Online Premieres Too

Image : Self- portrait by Chila Kumari Singh Burman Welcome back to the festival, which this Dive deep into our Extra-Ordinary Lives strand with amazing dramas and year has evolved into a hybrid festival. documentaries from across South Asia. Including the must-see Ahimsa: Gandhi, You can watch it in cinemas in London, The Power of The Powerless, a documentary on the incredible global impact of Birmingham, and Manchester, or on Gandhi’s non-violence ideas; Abhijaan, an inspiring biopic exploring the life of your own sofa at home, via our digital the late and great Bengali actor Soumitra Chatterjee; Black comedy Ashes On a site www.LoveLIFFatHome.com, that Road Trip; and Tiger Award winner at Rotterdam Pebbles. Look out for selected is accessible anywhere in the United online premieres too. Kingdom. Our talks and certain events We also introduce a new strand dedicated to ecology-related films, calledSave CARY RAJINDER SAWHNEY are also accessible worldwide. The Planet, with some stirring features about lives affected by deforestation and rising sea levels, and how people are meeting the challenge. A big personal thanks to all our audiences who stayed with the festival last We are expecting a host of special guests as usual and do check out our brilliant year and helped make it one of the few success stories in the film industry. This online In Conversations with Indian talent in June - where we will be joined year’s festival is dedicated to you with love. by Bollywood Director Karan Johar, and rapidly rising talented actors Shruti Highlights of this year’s festival include our inspiring Opening Night Gala Haasan and Janhvi Kapoor, as well as featuring some very informative online WOMB about one woman gender activist who incredibly walks the entire Q&As on all our films.