The Notion and Significance of Ma[Rifa in Sufism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

The Kāshif Al- Ilbās of Shaykh Ibrāhīm Niasse: Analysis of the Text

THE KĀSHIF AL- ILBĀS OF SHAYKH IBRĀHĪM NIASSE: ANALYSIS OF THE TEXT Zachary Wright The Kāshif al- Ilbās was the magnum opus of one of twentieth- century West Africa’s most infl uential Muslim leaders, Shaykh al- Islam Ibrāhīm ‘Abd- Allāh Niasse (1900–1975). No Sufi master can be reduced to a single text, and the mass following of Shaykh Ibrāhīm, described as possibly the largest single Muslim movement in modern West Africa,1 most certainly found its primary inspiration in the personal example and spiritual zeal of the Shaykh rather than in written words. The analysis of this highly signifi - cant West African Arabic text cannot escape the essential paradox of Sufi writing: putting the ineffable experience of God into words. The Kāshif re- peatedly insisted that the communication of “experiential spiritual knowl- edge” (ma‘rifa)—the key concept on which Shaykh Ibrāhīm’s movement was predicated and the subject which occupies the largest portion of the 1 Portions of this article are included in the introduction to the forthcoming publication: Zachary Wright, Muhtar Holland, and Abdullahi El-Okene, trans., The Removal of Confu- sion Concerning the Flood of the Saintly Seal, Aḥmad al-Tijānī: A Translation of Kāshif al-Ilbās ‘an fayḍa al-khatm Abī al-‘Abbās by Shaykh al-Islam al-Ḥājj Ibrāhīm b. ‘Abd- Allāh Niasse (Louisville, Ky.: Fons Vitae, 2010). See Mervyn Hiskett, The Development of Islam in West Africa (London: Longman, 1984), 287. See also Ousmane Kane, John Hunwick, and Rüdiger Seesemann, “Senegambia I: The Niassene Tradition,” in The Writ- ings of Western Sudanic Africa, vol. -

Books on Logic (Manṭiq) and Dialectics (Jadal)

_full_journalsubtitle: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World _full_abbrevjournaltitle: MUQJ _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0732-2992 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 2211-8993 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_volume: 14 _full_pubyear: 2019 _full_journaltitle: Muqarnas Online _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_fpage: 000 _full_lpage: 000 _full_articleid: 10.1163/22118993_01401P008 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) 891 KHALED EL-ROUAYHEB BOOKS ON LOGIC (MANṭIQ) AND DIALECTICS (JADAL) The ordering of subjects in the palace library inventory Secrets in Commenting upon the Dawning of Lights); prepared by ʿAtufi seems to reflect a general sense of the fourth entry has “The Commentary on the Logic of rank. Logic and dialectics appear toward the end of the Maṭāliʿ al-anwār, entitled Lawāmiʿ al-asrār,” again with inventory, suggesting that they were ranked relatively no indication of the author. low. Nevertheless, these disciplines were regularly stud- To take another example, ʿAtufi has four entries on ied in Ottoman colleges (madrasas). The cataloguer the same Quṭb al-Din al-Razi’s commentary on another ʿAtufi himself contributed to them, writing a commen- handbook of logic, al-Risāla al-Shamsiyya (The Epistle tary on Īsāghūjī (Introduction), the standard introduc- for Shams al-Din) by Najm al-Din al-Katibi (d. 1276). The tory handbook -

An Analysis of Ibn Al-'Arabi's Al-Insan Al-Kamil, the Perfect Individual, with a Brief Comparison to the Thought of Sir Muhammad Iqbal

v» fT^V 3^- b An Analysis of Ibn al-'Arabi's al-Insan al-Kamil, the Perfect Individual, with a Brief Comparison to the Thought of Sir Muhammad Iqbal Rebekah Zwanzig, Master of Arts Philosophy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Philosophy, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © May, 2008 JAMES A GffiSON LIBRARY BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES ON 'I I,, >-•• Abstract: This thesis analyzes four philosophical questions surrounding Ibn al-'Arabi's concept of the al-iman al-kamil, the Perfect Individual. The Introduction provides a definition of Sufism, and it situates Ibn al-'Arabi's thought within the broader context of the philosophy of perfection. Chapter One discusses the transformative knowledge of the Perfect Individual. It analyzes the relationship between reason, revelation, and intuition, and the different roles they play within Islam, Islamic philosophy, and Sufism. Chapter Two discusses the ontological and metaphysical importance of the Perfect Individual, exploring the importance of perfection within existence by looking at the relationship the Perfect Individual has with God and the world, the eternal and non-eternal. In Chapter Three the physical manifestations of the Perfect Individual and their relationship to the Prophet Muhammad are analyzed. It explores the Perfect Individual's roles as Prophet, Saint, and Seal. The final chapter compares Ibn al-'Arabi's Perfect Individual to Sir Muhammad Iqbal's in order to analyze the different ways perfect action can be conceptualized. It analyzes the relationship between freedom and action. \ ^1 Table of Contents "i .. I. Introduction 4 \. -

Abd Al-Karim Al-Jili

‛ABD AL-KAR ĪM AL-JĪLĪ: Taw ḥīd, Transcendence and Immanence by NICHOLAS LO POLITO A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The present thesis is an attempt to understand ‛Abd Al-Kar īm Al-Jīlī’s thought and to illustrate his original contribution to the development of medieval Islamic mysticism. In particular, it maintains that far from being an obscure disciple of Ibn ‛Arab ī, Al-Jīlī was able to overcome the apparent contradiction between the doctrinal assumption of a transcendent God and the perception of divine immanence intrinsic in God’s relational stance vis-à-vis the created world. To achieve this, this thesis places Al-Jīlī historically and culturally within the Sufi context of eighth-ninth/fourteenth-fifteenth centuries Persia, describing the world in which he lived and the influence of theological and philosophical traditions on his writings, both from within and without the Islamic world. -

From Rabi`A to Ibn Al-Färich Towards Some Paradigms of the Sufi Conception of Love

From Rabi`a to Ibn al-Färich Towards Some Paradigms of the Sufi Conception of Love By Suleyman Derin ,%- Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of doctor of philosophy Department of Arabic and 1Viiddle Eastern Studies The University of Leeds The candidate confirms that the work submitted is his own work and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. September 1999 ABSTRACT This thesis aims to investigate the significance of Divine Love in the Islamic tradition with reference to Sufis who used the medium of Arabic to communicate their ideas. Divine Love means the mutual love between God and man. It is commonly accepted that the Sufis were the forerunners in writing about Divine Love. However, there is a relative paucity of literature regarding the details of their conceptions of Love. Therefore, this attempt can be considered as one of the first of its kind in this field. The first chapter will attempt to define the nature of love from various perspectives, such as, psychology, Islamic philosophy and theology. The roots of Divine Love in relation to human love will be explored in the context of the ideas that were prevalent amongst the Sufi authors regarded as authorities; for example, al-Qushayri, al-Hujwiri and al-Kalabadhi. The second chapter investigates the origins Of Sufism with a view to establishing the role that Divine Love played in this. The etymological derivations of the term Sufi will be referred to as well as some early Sufi writings. It is an undeniable fact that the Qur'an and tladith are the bedrocks of the Islamic religion, and all Muslims seek to justify their ideas with reference to them. -

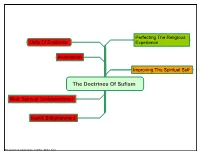

The Doctrines of Sufism

Perfecting The Religious Unity Of Existence Experience Annihilation Improving The Spiritual Self The Doctrines Of Sufism Wali: Spiritual Guide/sainthood Kashf: Enlightenment The doctrines of sufism.mmap • 3/4/2006 • Mindjet Team Emphasizes perception, maarifa leading to direct knowledge of Self and God, and Sufism uses the heart as its medium Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as The Context: (The Approaches To its medium, and subjects reason to Faith And Understanding) Kalam revelation Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as Philosophy its medium AL BAQARA Al Junayd Al Hallaj Annihilation By Examples Taqwa: Piety Sobriety The Goals Of The Spiritual Journey Paradox and biwelderment Intoxication QAAF The Consequence Of Annihilation Annihilation Abu Bakr (RAA): Incapacity to perceive is perception Perplexity Results from the negation in the first part of the Shahada (fana) AL HADEED And from the affirmation of the Living the Shahada subsistence in the second part of the Shahada: (Baqa) Be witness to the divine reality, and eliminate the egocentric self Living the Tawheed The Motivation For Annihilation Start as a stone Be shuttered by the divine light of the Self transformation divine reality you witness Emerge restructed as a jewel The Origins Of Annihilation AL RAHMAN Annihilation.mmap • 3/6/2006 • Mindjet Team Born and Raised in Baghdad (died in 910 or 198 H) His education focused on Fiqh and Hadith He studied under the Jurist Abu Thawr: An extraordinary jurist started as a Hanafii, then followed the Shafi school once al Imam Al Shafi came to Baghdad. -

A Study on Sayyid Qutb a Dissertation Submitted To

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO READING A RADICAL THINKER: A STUDY ON SAYYID QUTB A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF NEAR EASTERN LANGUAGES AND CIVILIZATIONS BY LAITH S. SAUD CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2017 Table of Contents Table of Figures ............................................................................................................................................. iii Chapter One: Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 Biography ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Chapter Review .......................................................................................................................................................... 4 Chapter Two: Reading Qutb Theologically; Toward a Method for Reading an Islamist ............................................................................................................................................................................ 10 The Current State of Inquiries on Qutb: The Fundamentalist par excellence ............................. 11 Theology, Epistemology, and Logic: Toward a Methodology .............................................................. 17 What is Qutb’s General Cosmology? ............................................................................................................. -

Two Modern Radical Exegetes of the Qur'an

Master Thesis For fulfillment of MA Theology and Religious Studies, Leiden University Supervisor: Dhr. Dr. N. Kaptein Second reader: Dhr. Prof. dr. M. Berger Two modern radical exegetes of the Qur’an The influence of Sayyid Qutb on Abu Zayd’s humanistic hermeneutics Student: Rashwan Bafati, s0729361 Contents 1. Introduction 1.1. The peculiar case of Sayyid Qutb’s influence on Abu Zayd 1.2. Literature review 1.3. Research questions and hypotheses 2. Frameworks, tools and methods for the comparison 2.1. The literary theory of the Qur’an 2.2. Shepard’s typology and Lee’s Search for Islamic authenticity. The framework of postmodernism 2.3. Essential questions of theology. Epistemology, nature of the Qur’an and predestination 3. Sayyid Qutb and his tafsir al-haraka, dynamic yaqin 3.1. Qutb’s epistemology 3.2. Qutb on the nature of the Qur’an 3.3. Qutb on predetermination 3.4. Qutb’s position in modern Islamic theology. A return to dynamic unity (tawhid) 3.5. Qutb and the literary theory of the Qur’an. An impressionist approach 4. Abu Zayd and his humanistic hermeneutics, dynamic ta’wil 4.1. Abu Zayd’s epistemology 4.2. Abu Zayd on the nature of the Qur’an 4.3. Abu Zayd on predetermination 4.4. Aby Zayd’s position in modern Islamic theology. A musical unity of pluralist chords 4.5. Abu Zayd and the literary theory of the Qur’an. An expressionist approach 5. Conclusion. Humanism as a divine system. And humanism as a choice. Abu Zayd, the humanist of Islam 6. -

Ala Man Ankara Al-Tasa

A TRANSLATION, WITH CRITICAL INTRODUCTION, OF SHAYKH AL-`ALAWI’S AL-RISĀLAH AL-QAWL AL-MA`RŪF FĪ AL-RADD `ALĀ MAN ANKARA AL-TASAWWUF (A KIND WORD IN RESPONSE TO THOSE WHO REJECT SUFISM) MOGAMAT MAHGADIEN HENDRICKS Student number 2352068 A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement of the degree of Magister Artium in the Department of Foreign Languages, University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Professor Yasien Mohamed 14th of November 2005 CONTENTS KEYWORDS................................................................................................................................................i ABSTRACT.................................................................................................................................................ii DECLARATION........................................................................................................................................iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT.........................................................................................................................iv TRANSLATOR’S INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... I Section One: Literary works in defence of the Sufis...........................................................................I Section Two: The life of Shaykh Sidi Aḥmad ibn Muṣṭafā al-`Alāwi............................................... VI Section Three: The legacy of Shaykh Sidi Ahmad ibn Muṣṭafā al-`Alāwi .......................................VIII Section Four: -

1. Introduction to Ecstatic Readings

1. INTRODUCTION TO ECSTATIC READINGS 1.0. PRELIMINARY REMARKS: TITE PT,RPOSE AND MEANS According to the hypothesis underlying this study, Syriac and Sufi texts refer repeatedly to and deal with something "mystical" which is absolutely nonlin- guistic in nature, yet is expr€ssed linguistically under the conditions and restric- tions of natu¡al language; this something is an important factor constituting the character ofthe discourse, but it does not submit to being an object ofresearch. For this ¡eason, we must place it in brackets and content ou¡selves with the docu- mented process of expression and interpretation. The purpose of this study is to undertake a systematic survey of the different constituents ofecstatic readings in Syriac ascetic literature, including the process of expression and interpretation (and manifestation, as fa¡ as possible), and to present this together with a corresponding analysis of classical Sufism as it is manifested in its authoritative literature, and finally, to make concluding rema¡ks conceming common featu¡es and differences between the traditions. The concept of mystical experience is employed in the broad sense, covering the concepts of"ecstasy" and "trance", fr¡rther details (and the reasons for the lack ofprecise definitions for any ofthese concepts) being discussed below (p. 38 ff.). The Syriac corpus consists of more than I ,500 pages of literature by about l0 authors, the most important of whom a¡e Isaac of Nineveh, John of Dalyathq and 'Abdiðo' (Joseph) the Seer. All the main sources are basically internal monastic correspondence from one hermit to another, the result being a great variety of relatively frank descriptions of inner experiences.