Abd Al-Karim Al-Jili

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

“Fight Is an Inside Path” – a Minor Field Study of How Members of Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order Perceive Religious Freedom in Mexico

Södertörn University | School of Historical and Contemporary Studies Bachelor thesis 15 hp | Religious studies | Fall 2014 The program of Journalism target religious studies “Fight is an inside path” – A minor field study of how members of Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order perceive religious freedom in Mexico By: Sandra Forsvik Supervisor in Sweden: Simon Sorgenfrei Supervisor in Mexico: Israel Rojas Cámara Abstract The interests for academic studies of contemporary Sufism and Sufism in non-Islamic countries have become more popular, but little has been done in Latin America. The studies of Islam in this continent are limited and studies on Sufism in Mexico seem to be an unexplored area. As a student of journalism target religion I see this as an important topic that can generate new information for the study of Sufism. This thesis is therefore aimed to describe the group of Sufis I have chosen to study, Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order in Mexico, linked to Human Rights in form of how members of the Sufi order perceive Religious Freedom in Mexico. A minor field study was carried out in Colonia Roma, Mexico City during October and November 2014. The place was chosen because this is the place where Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order exists in Mexico. The investigation is qualitative and based on an ethnographic study of eight weeks and semi structured interviews with three dervishes of the Sufi order, where two of them are men and one is a woman. Based on my purpose I have formulated the following questions: – How do members of Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi -

The Notion and Significance of Ma[Rifa in Sufism

Journal of Islamic Studies 13:2 (2002) pp. 155–181 # Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies 2002 THE NOTION AND SIGNIFICANCE OF MA[RIFA IN SUFISM REZA SHAH-KAZEMI London At the heart of the Sufi notion of ma[rifa there lies a paradox that is as fruitful in spiritual terms as it is unfathomable on the purely mental plane: on the one hand, it is described as the highest knowledge to which the individual has access; but on the other, the ultimate content of this knowledge so radically transcends the individual that it comes to be described in terms of ‘ignorance’. In one respect, it is said to be a light that illumines and clarifies, but in another respect its very brilliance dazzles, blinds, and ultimately extinguishes the one designated as a ‘knower’ (al-[a¯rif ).1 This luminous knowledge that demands ‘unknowing’ is also a mode of being that demands effacement; and it is the conjunction between perfect knowledge and pure being that defines the ultimate degree of ma[rifa. Since such a conjunction is only perfectly realized in the undifferentiated unity of the Absolute, it follows that it can only be through the Absolute that the individual can have access to this ultimate degree of ma[rifa, thus becoming designated not as al-[a¯rif, tout court, but as al-[a¯rif bi-Lla¯h: the knower through God. The individual is thus seen as participating in Divine knowledge rather than possessing it, the attribute of knowledge pertaining in fact to God and not himself. In this light, the definition of tasawwuf given by al-Junayd (d. -

Books on Logic (Manṭiq) and Dialectics (Jadal)

_full_journalsubtitle: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World _full_abbrevjournaltitle: MUQJ _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0732-2992 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 2211-8993 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_volume: 14 _full_pubyear: 2019 _full_journaltitle: Muqarnas Online _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_fpage: 000 _full_lpage: 000 _full_articleid: 10.1163/22118993_01401P008 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) 891 KHALED EL-ROUAYHEB BOOKS ON LOGIC (MANṭIQ) AND DIALECTICS (JADAL) The ordering of subjects in the palace library inventory Secrets in Commenting upon the Dawning of Lights); prepared by ʿAtufi seems to reflect a general sense of the fourth entry has “The Commentary on the Logic of rank. Logic and dialectics appear toward the end of the Maṭāliʿ al-anwār, entitled Lawāmiʿ al-asrār,” again with inventory, suggesting that they were ranked relatively no indication of the author. low. Nevertheless, these disciplines were regularly stud- To take another example, ʿAtufi has four entries on ied in Ottoman colleges (madrasas). The cataloguer the same Quṭb al-Din al-Razi’s commentary on another ʿAtufi himself contributed to them, writing a commen- handbook of logic, al-Risāla al-Shamsiyya (The Epistle tary on Īsāghūjī (Introduction), the standard introduc- for Shams al-Din) by Najm al-Din al-Katibi (d. 1276). The tory handbook -

A Study and Analysis of Sanai's Illustration Techniques with A

Propósitos y Representaciones Sep.-Dec. 2020, Vol. 8, N° 3, e623 ISSN 2307-7999 Monographic: Educational management and teaching skills e-ISSN 2310-4635 http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2020.v8n3.623 CONFERENCES A Study and Analysis of Sanai's Illustration Techniques With a Mountain in Divan and Hadigheh al-Haqiqa Un estudio y análisis de las técnicas de ilustración de Sanai con una montaña en Divan y Hadigheh al-Haqiqa Zahra Ghazi Karbasi PhD Student in Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Neishabur Branch, Iran Batool Fakhr al-Islam Member of the Department of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Neishabur Branch, Iran Akbar Shabani Member of the Department of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Neishabur Branch, Iran. Mehdi Norouz Member of the Department of Persian Language and Literature, Islamic Azad University, Neishabur Branch, Iran. Received 01-27-20 Revised 03-03-20 Accepted 05-17-20 On line 07-30-20 *Correspondence Cite as: Email: [email protected] Ghazi Karbasi, Z., Fakhr al-Islam, B., Shabani, A., Norouz, M. (2020). A Study and Analysis of Sanai's Illustration Techniques With a Mountain in Divan and Hadigheh al-Haqiqa. Propósitos y Representaciones, 8(3), e623. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.20511/pyr2020.v8n3.623 © Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Vicerrectorado de Investigación, 2020. This article is distributed under license CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 International (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). A Study and Analysis of Sanai's Illustration Techniques With a Mountain in Divan and Hadigheh al-Haqiqa Summary Sanai is considered one of the prominent mystic poets in the field of Persian literature. -

Path(S) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community”

“Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” By Jaison Carter A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair Professor Charles Hirschkind Professor Stefania Pandolfo Professor Ula Y. Taylor Spring 2018 Abstract “Path(s) of Remembrance: Memory, Pilgrimage, and Transmission in a Transatlantic Sufi Community” by Jaison Carter Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Professor Mariane Ferme, Chair The Mustafawiyya Tariqa is a regional spiritual network that exists for the purpose of assisting Muslim practitioners in heightening their level of devotion and knowledges through Sufism. Though it was founded in 1966 in Senegal, it has since expanded to other locations in West and North Africa, Europe, and North America. In 1994, protegé of the Tariqa’s founder and its most charismatic figure, Shaykh Arona Rashid Faye al-Faqir, relocated from West Africa to the United States to found a satellite community in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. This location, named Masjidul Muhajjirun wal Ansar, serves as a refuge for traveling learners and place of worship in which a community of mostly African-descended Muslims engage in a tradition of remembrance through which techniques of spiritual care and healing are activated. This dissertation analyzes the physical and spiritual trajectories of African-descended Muslims through an ethnographic study of their healing practices, migrations, and exchanges in South Carolina and in Senegal. By attending to manner in which the Mustafawiyya engage in various kinds of embodied religious devotions, forms of indebtedness, and networks within which diasporic solidarities emerge, this project explores the dispensations and transmissions of knowledge to Sufi practitioners across the Atlantic that play a part in shared notions of Black Muslimness. -

An Analysis of Ibn Al-'Arabi's Al-Insan Al-Kamil, the Perfect Individual, with a Brief Comparison to the Thought of Sir Muhammad Iqbal

v» fT^V 3^- b An Analysis of Ibn al-'Arabi's al-Insan al-Kamil, the Perfect Individual, with a Brief Comparison to the Thought of Sir Muhammad Iqbal Rebekah Zwanzig, Master of Arts Philosophy Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Philosophy, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © May, 2008 JAMES A GffiSON LIBRARY BROCK UNIVERSITY ST. CATHARINES ON 'I I,, >-•• Abstract: This thesis analyzes four philosophical questions surrounding Ibn al-'Arabi's concept of the al-iman al-kamil, the Perfect Individual. The Introduction provides a definition of Sufism, and it situates Ibn al-'Arabi's thought within the broader context of the philosophy of perfection. Chapter One discusses the transformative knowledge of the Perfect Individual. It analyzes the relationship between reason, revelation, and intuition, and the different roles they play within Islam, Islamic philosophy, and Sufism. Chapter Two discusses the ontological and metaphysical importance of the Perfect Individual, exploring the importance of perfection within existence by looking at the relationship the Perfect Individual has with God and the world, the eternal and non-eternal. In Chapter Three the physical manifestations of the Perfect Individual and their relationship to the Prophet Muhammad are analyzed. It explores the Perfect Individual's roles as Prophet, Saint, and Seal. The final chapter compares Ibn al-'Arabi's Perfect Individual to Sir Muhammad Iqbal's in order to analyze the different ways perfect action can be conceptualized. It analyzes the relationship between freedom and action. \ ^1 Table of Contents "i .. I. Introduction 4 \. -

Download Muqamaat-E-Ruh In

Muqamaat-E Ru’h ALLAH has created humans so that they can become ‘Insaan’. Insaan basically means ‘The one who forgets’. Ulama-e Zhaahir take this in the literal and worldly sense. Insaan forgets the vow taken in the World of the Souls and gets involved in all kind of evils in this 'Aalam-e Maadi. It is only ‘Tauba’ that can put him/her back on the right track. They quote a ‘Hadeeth: “If man did not commit sins, ALLAH would have destroyed the mankind and would have created another creation that would have sinned and asked for forgiveness so that HU could forgive”. Ulama-e Baatin believe in this but also talk about the ‘Insaan-e Haqeeqi’. This is explained by Sayyidina Makhdum Jahan Sharf-ul-Haq Wad Deen Ahmad Ya’hya Muniri (RA) of Silsila-E ‘Aaliya Suharwardiya in his Maktoobat under the Title ‘Tauheed’. He talks about the following four levels of Tauheed: 1. Tauheed-e Munafiqeen 2. Tauheed-e 'Aamiyana and Tauheed-e Mutakallamin 3. Tauheed-e 'Aarifana 4. Tauheed-e Mauhidana It is the 4th level we are discussing here. There are three sublevel in it. In this level, Tajalliaat-e Sifaat-e Ilaahi descend on the heart with such an intensity that the person forgets everything. In the second sublevel, the person is involved in such a depth that he/she forgets himself/herself. In the third sublevel, he/she forgets about the forgetting. This is also known as Fanaa 'Anil Fanaa. The person who achieves this level of Tauheed is known as 'Insaan', the one who forgets everything in the Divine Love, forgets himself/herself and then forgets about this forgetting. -

The Correlation of Islamic Law Basics and Linguistics

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Politics and Law Available online at www.sciarena.com 2016, Vol, 1 (1): 14-19 THE CORRELATION OF ISLAMIC LAW BASICS AND LINGUISTICS Sansyzbay Chukhanov1, Kairat Kurmanbayev2 1Ph.D Student, Faculty of Islamic Studies, Egypt University of Islamic Culture Nur Mubarak, Kazakhstan, phone: +7 (777) 2727171, e-mail: [email protected] 2Ph.D doctor of Egypt University of Islamic Culture Nur Mubarak. 050040, Kazakhstan (Phone: +7 (747) 5556575 e-mail: [email protected]) Abstract: Any domain of science in Islam derives its basic concepts, theories, methodology, and terminology within an Arabic language context. The language certainly benefited from Islamic science, particularly with respect to methodology. However, Arabic linguistics added more than it took from “Islamic law basics.” This article considers the correlation of Islamic law basics and Arabic language linguistics, alongside similarities in the study of the two fields. This analysis compares the scientific-methodological basics resulting from applying linguistic-semantic principles in Arabic language with shariat norms given by Muslim legal experts to resolve different real-world cases. Chief among the comparisons made are the differences noted between the Hanafi school of law, a very early understanding of Islamic law basics (usul al- fiqh), and principles of the majority of modern legal experts. Keywords: linguistics, Arabic language, tafsir (interpretation), hadith, fiqh. Introduction One of the most important branches of usul al-fiqh is the study of language. Linguistics includes principles relating to the way in which words convey their meanings, and to the clarity and ambiguity of words and their interpretation. The knowledge of these principles is essential to the proper understanding of the authoritative texts from which the legal rulings of Islamic law are deduced. -

Sufism: in the Spirit of Eastern Spiritual Traditions

92 Sufism: In the Spirit of Eastern Spiritual Traditions Irfan Engineer Volume 2 : Issue 1 & Volume Center for the Study of Society & Secularism, Mumbai [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 93 Introduction Sufi Islam is a mystical form of Islamic spirituality. The emphasis of Sufism is less on external rituals and more on the inward journey. The seeker searches within to make oneself Insaan-e-Kamil, or a perfect human being on God’s path. The origin of the word Sufism is in tasawwuf, the path followed by Sufis to reach God. Some believe it comes from the word suf (wool), referring to the coarse woollen fabric worn by early Sufis. Sufiya also means purified or chosen as a friend of God. Most Sufis favour the origin of the word from safa or purity; therefore, a Sufi is one who is purified from worldly defilements. The essence of Sufism, as of most religions, is to reach God, or truth or absolute reality. Characteristics of Sufism The path of Sufism is a path of self-annihilation in God, also called afanaa , which means to seek permanence in God. A Sufi strives to relinquish worldly and even other worldly aims. The objective of Sufism is to acquire knowledge of God and achieve wisdom. Sufis avail every act of God as an opportunity to “see” God. The Volume 2 : Issue 1 & Volume Sufi “lives his life as a continuous effort to view or “see” Him with a profound, spiritual “seeing” . and with a profound awareness of being continuously overseen by Him” (Gulen, 2006, p. xi-xii). -

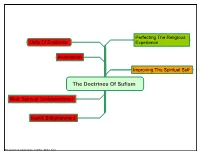

The Doctrines of Sufism

Perfecting The Religious Unity Of Existence Experience Annihilation Improving The Spiritual Self The Doctrines Of Sufism Wali: Spiritual Guide/sainthood Kashf: Enlightenment The doctrines of sufism.mmap • 3/4/2006 • Mindjet Team Emphasizes perception, maarifa leading to direct knowledge of Self and God, and Sufism uses the heart as its medium Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as The Context: (The Approaches To its medium, and subjects reason to Faith And Understanding) Kalam revelation Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as Philosophy its medium AL BAQARA Al Junayd Al Hallaj Annihilation By Examples Taqwa: Piety Sobriety The Goals Of The Spiritual Journey Paradox and biwelderment Intoxication QAAF The Consequence Of Annihilation Annihilation Abu Bakr (RAA): Incapacity to perceive is perception Perplexity Results from the negation in the first part of the Shahada (fana) AL HADEED And from the affirmation of the Living the Shahada subsistence in the second part of the Shahada: (Baqa) Be witness to the divine reality, and eliminate the egocentric self Living the Tawheed The Motivation For Annihilation Start as a stone Be shuttered by the divine light of the Self transformation divine reality you witness Emerge restructed as a jewel The Origins Of Annihilation AL RAHMAN Annihilation.mmap • 3/6/2006 • Mindjet Team Born and Raised in Baghdad (died in 910 or 198 H) His education focused on Fiqh and Hadith He studied under the Jurist Abu Thawr: An extraordinary jurist started as a Hanafii, then followed the Shafi school once al Imam Al Shafi came to Baghdad.