Mysticism and Sexuality in Sufi Thought and Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Sufi Reading of Jesus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals... Representations of Jesus in Islamic Mysticism: Defining the „Sufi Jesus‟ Milad Milani Created from the wine of love, Only love remains when I die. (Rumi)1 I‟ve seen a world without a trace of death, All atoms here have Jesus‟ pure breath. (Rumi)2 Introduction This article examines the limits touched by one religious tradition (Islam) in its particular approach to an important symbolic structure within another religious tradition (Christianity), examining how such a relationship on the peripheries of both these faiths can be better apprehended. At the heart of this discourse is the thematic of love. Indeed, the Qur’an and other Islamic materials do not readily yield an explicit reference to love in the way that such a notion is found within Christianity and the figure of Jesus. This is not to say that „love‟ is altogether absent from Islamic religion, since every Qur‟anic chapter, except for the ninth (surat at-tawbah), is prefaced In the Name of God; the Merciful, the Most Kind (bismillahi r-rahmani r-rahim). Love (Arabic habb; Persian Ishq), however, becomes a foremost concern of Muslim mystics, who from the ninth century onward adopted the theme to convey their experience of longing for God. Sufi references to the theme of love starts with Rabia al-Adawiyya (717-801) and expand outward from there in a powerful tradition. Although not always synonymous with the figure of Jesus, this tradition does, in due course, find a distinct compatibility with him. -

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality: a Study of Majlis Dhikr Groups

Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Rituals of Islamic Spirituality A STUDY OF MAJLIS DHIKR GROUPS IN EAST JAVA Arif Zamhari THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY E P R E S S E P R E S S Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/islamic_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Zamhari, Arif. Title: Rituals of Islamic spirituality: a study of Majlis Dhikr groups in East Java / Arif Zamhari. ISBN: 9781921666247 (pbk) 9781921666254 (pdf) Series: Islam in Southeast Asia. Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Islam--Rituals. Islam Doctrines. Islamic sects--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Sufism--Indonesia--Jawa Timur. Dewey Number: 297.359598 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changesthat the author may have decided to undertake. -

Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism

Journal of Education & Social Policy Vol. 1 No. 1; June 2014 Understanding the Concept of Islamic Sufism Shahida Bilqies Research Scholar, Shah-i-Hamadan Institute of Islamic Studies University of Kashmir, Srinagar-190006 Jammu and Kashmir, India. Sufism, being the marrow of the bone or the inner dimension of the Islamic revelation, is the means par excellence whereby Tawhid is achieved. All Muslims believe in Unity as expressed in the most Universal sense possible by the Shahadah, la ilaha ill’Allah. The Sufi has realized the mysteries of Tawhid, who knows what this assertion means. It is only he who sees God everywhere.1 Sufism can also be explained from the perspective of the three basic religious attitudes mentioned in the Qur’an. These are the attitudes of Islam, Iman and Ihsan.There is a Hadith of the Prophet (saw) which describes the three attitudes separately as components of Din (religion), while several other traditions in the Kitab-ul-Iman of Sahih Bukhari discuss Islam and Iman as distinct attitudes varying in religious significance. These are also mentioned as having various degrees of intensity and varieties in themselves. The attitude of Islam, which has given its name to the Islamic religion, means Submission to the Will of Allah. This is the minimum qualification for being a Muslim. Technically, it implies an acceptance, even if only formal, of the teachings contained in the Qur’an and the Traditions of the Prophet (saw). Iman is a more advanced stage in the field of religion than Islam. It designates a further penetration into the heart of religion and a firm faith in its teachings. -

In Their Own Words: Voices of Jihad

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as CHILD POLICY a public service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION Jump down to document ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT 6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and PUBLIC SAFETY effective solutions that address the challenges facing SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY the public and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Support RAND TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Purchase this document WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Learn more about the RAND Corporation View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. in their own words Voices of Jihad compilation and commentary David Aaron Approved for public release; distribution unlimited C O R P O R A T I O N This book results from the RAND Corporation's continuing program of self-initiated research. -

The Birth of Al-Wahabi Movement and Its Historical Roots

The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Original Document Information ~o·c·u·m·e·n~tI!i#~:I~S=!!G~Q~-2!110~0~3~-0~0~0~4'!i66~5~9~"""5!Ii!IlI on: nglis Title: Correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General Military Intelligence irectorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of AI-Wahhabiyyah ovement and its Historical Roots" age: ARABIC otal Pages: 53 nclusive Pages: 52 versized Pages: PAPER ORIGINAL IRAQI FREEDOM e: ountry Of Origin: IRAQ ors Classification: SECRET Translation Information Translation # Classification Status Translating Agency ARTIAL SGQ-2003-00046659-HT DIA OMPLETED GQ-2003-00046659-HT FULL COMPLETED VTC TC Linked Documents I Document 2003-00046659 ISGQ-~2~00~3~-0~0~04~6~6~5~9-'7':H=T~(M~UI:7::ti""=-p:-a"""::rt~)-----------~II • cmpc-m/ISGQ-2003-00046659-HT.pdf • cmpc-mIlSGQ-2003-00046659.pdf GQ-2003-00046659-HT-NVTC ·on Status: NOT AVAILABLE lation Status: NOT AVAILABLE Related Document Numbers Document Number Type Document Number y Number -2003-00046659 161 The classification markings are original to the Iraqi documents and do not reflect current US classification. Keyword Categories Biographic Information arne: AL- 'AMIRI, SA'IO MAHMUO NAJM Other Attribute: MILITARY RANK: Colonel Other Attribute: ORGANIZATION: General Military Intelligence Directorate Photograph Available Sex: Male Document Remarks These 53 pages contain correspondence, dated 24 Sep 2002, within the General i1itary Intelligence Directorate (GMID), regarding a research study titled, "The Emergence of I-Wahhabiyyah Movement and its Historical Roots". -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE ALEXANDER D. KNYSH Professor of Islamic Studies Department of Middle East Studies University of Michigan 202 Thayer Building Ann Arbor, MI 48104-1608, USA Tel. (734) 615-1963; e-mail: [email protected] EDUCATION: Institute for Oriental Studies, USSR Academy of Sciences, Leningrad (presently St. Petersburg), Ph.D. in Islamic Studies, 1980-1986 State University of Leningrad (presently St. Petersburg), Department of Oriental Studies, B.A./M.A. in Arabic Literature and Culture, 1974-1979 (Honors) ACADEMIC POSITIONS: 1997-present, Professor of Islamic Studies, University of Michigan May-June, 2017, Visiting Professor/Researcher, Forschungszentrum “Bildung und Religion”, Georg-August-Universität, Göttingen, Germany, http://www.uni-goettingen.de/de/das- zentrum/110217.html. 2014-2015, European Association of Institutes for Advanced Study (EURIAS); Senior Fellow (http://www.2018-2019.eurias- fp.eu/fellows?promotion=89&city=Helsinki%2C+Finland&felowship_category=All&discipline =All), The Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies, Helsinki, Finland. 2013-present, Project Director, Political Islam/Islamism: Theory and Practice in Comparative and Historical Perspective. St. Petersburg State University, Russian Federation (http://islab.spbu.ru/). 2012 (May-June), Visiting Professor of Islamic Studies, L.N. Gumilyov Eurasian National University, Astana, Kazakhstan 2011 (December), Visiting Professor of Islamic history, Kazakh National University named after al-Farabi, Almaty, Kazakhstan 2008-2009, Associate Director, Center for Middle Eastern and North African Studies, University of Michigan Winter 2008, Visiting Professor of Islamic studies, Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. 2007-2008, Fellow, Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, Washington D.C. 2006-2010, Co-Director, Islamic Studies Initiative, interdisciplinary program funded for the Page | 2 Office of the Provost, the Dean of the College of Literature Science and the Arts, and the International Institute, University of Michigan. -

The Notion and Significance of Ma[Rifa in Sufism

Journal of Islamic Studies 13:2 (2002) pp. 155–181 # Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies 2002 THE NOTION AND SIGNIFICANCE OF MA[RIFA IN SUFISM REZA SHAH-KAZEMI London At the heart of the Sufi notion of ma[rifa there lies a paradox that is as fruitful in spiritual terms as it is unfathomable on the purely mental plane: on the one hand, it is described as the highest knowledge to which the individual has access; but on the other, the ultimate content of this knowledge so radically transcends the individual that it comes to be described in terms of ‘ignorance’. In one respect, it is said to be a light that illumines and clarifies, but in another respect its very brilliance dazzles, blinds, and ultimately extinguishes the one designated as a ‘knower’ (al-[a¯rif ).1 This luminous knowledge that demands ‘unknowing’ is also a mode of being that demands effacement; and it is the conjunction between perfect knowledge and pure being that defines the ultimate degree of ma[rifa. Since such a conjunction is only perfectly realized in the undifferentiated unity of the Absolute, it follows that it can only be through the Absolute that the individual can have access to this ultimate degree of ma[rifa, thus becoming designated not as al-[a¯rif, tout court, but as al-[a¯rif bi-Lla¯h: the knower through God. The individual is thus seen as participating in Divine knowledge rather than possessing it, the attribute of knowledge pertaining in fact to God and not himself. In this light, the definition of tasawwuf given by al-Junayd (d. -

Books on Logic (Manṭiq) and Dialectics (Jadal)

_full_journalsubtitle: An Annual on the Visual Cultures of the Islamic World _full_abbrevjournaltitle: MUQJ _full_ppubnumber: ISSN 0732-2992 (print version) _full_epubnumber: ISSN 2211-8993 (online version) _full_issue: 1 _full_volume: 14 _full_pubyear: 2019 _full_journaltitle: Muqarnas Online _full_issuetitle: 0 _full_fpage: 000 _full_lpage: 000 _full_articleid: 10.1163/22118993_01401P008 _full_alt_author_running_head (change var. to _alt_author_rh): 0 _full_alt_articletitle_running_head (change var. to _alt_arttitle_rh): Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) Manuscripts on Logic (manṭiq) and Dialectics (jadal) 891 KHALED EL-ROUAYHEB BOOKS ON LOGIC (MANṭIQ) AND DIALECTICS (JADAL) The ordering of subjects in the palace library inventory Secrets in Commenting upon the Dawning of Lights); prepared by ʿAtufi seems to reflect a general sense of the fourth entry has “The Commentary on the Logic of rank. Logic and dialectics appear toward the end of the Maṭāliʿ al-anwār, entitled Lawāmiʿ al-asrār,” again with inventory, suggesting that they were ranked relatively no indication of the author. low. Nevertheless, these disciplines were regularly stud- To take another example, ʿAtufi has four entries on ied in Ottoman colleges (madrasas). The cataloguer the same Quṭb al-Din al-Razi’s commentary on another ʿAtufi himself contributed to them, writing a commen- handbook of logic, al-Risāla al-Shamsiyya (The Epistle tary on Īsāghūjī (Introduction), the standard introduc- for Shams al-Din) by Najm al-Din al-Katibi (d. 1276). The tory handbook -

Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Oludamini Ogunnaike Harvard University, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 17 Article 10 Issue 2 October 2013 10-2-2013 Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Oludamini Ogunnaike Harvard University, [email protected] Recommended Citation Ogunnaike, Oludamini (2013) "Inception and Ibn 'Arabi," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 17 : Iss. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol17/iss2/10 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inception and Ibn 'Arabi Abstract Many philosophers, playwrights, artists, sages, and scholars throughout the ages have entertained and developed the concept of life being a "but a dream." Few works, however, have explored this topic with as much depth and subtlety as the 13thC Andalusian Muslim mystic, Ibn 'Arabi. Similarly, few works of art explore this theme as thoroughly and engagingly as Chistopher Nolan's 2010 film Inception. This paper presents the writings of Ibn 'Arabi and Nolan's film as a pair of mirrors, in which one can contemplate the other. As such, the present work is equally a commentary on the film based on Ibn 'Arabi's philosophy, and a commentary on Ibn 'Arabi's work based on the film. The ap per explores several points of philosophical significance shared by the film and the work of the Sufi as ge, and their relevance to contemporary conversations in philosophy, religion, and art. Keywords Ibn 'Arabi, Sufism, ma'rifah, world as a dream, metaphysics, Inception, dream within a dream, mysticism, Christopher Nolan Author Notes Oludamini Ogunnaike is a PhD candidate at Harvard University in the Dept. -

Abd Al-Karim Al-Jili

‛ABD AL-KAR ĪM AL-JĪLĪ: Taw ḥīd, Transcendence and Immanence by NICHOLAS LO POLITO A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Theology and Religion School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham September 2010 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The present thesis is an attempt to understand ‛Abd Al-Kar īm Al-Jīlī’s thought and to illustrate his original contribution to the development of medieval Islamic mysticism. In particular, it maintains that far from being an obscure disciple of Ibn ‛Arab ī, Al-Jīlī was able to overcome the apparent contradiction between the doctrinal assumption of a transcendent God and the perception of divine immanence intrinsic in God’s relational stance vis-à-vis the created world. To achieve this, this thesis places Al-Jīlī historically and culturally within the Sufi context of eighth-ninth/fourteenth-fifteenth centuries Persia, describing the world in which he lived and the influence of theological and philosophical traditions on his writings, both from within and without the Islamic world. -

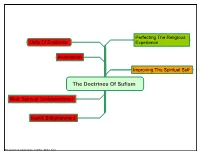

The Doctrines of Sufism

Perfecting The Religious Unity Of Existence Experience Annihilation Improving The Spiritual Self The Doctrines Of Sufism Wali: Spiritual Guide/sainthood Kashf: Enlightenment The doctrines of sufism.mmap • 3/4/2006 • Mindjet Team Emphasizes perception, maarifa leading to direct knowledge of Self and God, and Sufism uses the heart as its medium Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as The Context: (The Approaches To its medium, and subjects reason to Faith And Understanding) Kalam revelation Emphasizes reason, ilm leading to understanding of God, uses the Aaql as Philosophy its medium AL BAQARA Al Junayd Al Hallaj Annihilation By Examples Taqwa: Piety Sobriety The Goals Of The Spiritual Journey Paradox and biwelderment Intoxication QAAF The Consequence Of Annihilation Annihilation Abu Bakr (RAA): Incapacity to perceive is perception Perplexity Results from the negation in the first part of the Shahada (fana) AL HADEED And from the affirmation of the Living the Shahada subsistence in the second part of the Shahada: (Baqa) Be witness to the divine reality, and eliminate the egocentric self Living the Tawheed The Motivation For Annihilation Start as a stone Be shuttered by the divine light of the Self transformation divine reality you witness Emerge restructed as a jewel The Origins Of Annihilation AL RAHMAN Annihilation.mmap • 3/6/2006 • Mindjet Team Born and Raised in Baghdad (died in 910 or 198 H) His education focused on Fiqh and Hadith He studied under the Jurist Abu Thawr: An extraordinary jurist started as a Hanafii, then followed the Shafi school once al Imam Al Shafi came to Baghdad. -

Spiritual Rituals at Sufi Shrines in Punjab: a Study of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif Vol

Global Regional Review (GRR) URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.31703/grr.2019(IV-I).23 Spiritual Rituals at Sufi Shrines in Punjab: A Study of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif Vol. IV, No. I (Winter 2019) | Page: 209 ‒ 214 | DOI: 10.31703/grr.2019(IV-I).23 p- ISSN: 2616-955X | e-ISSN: 2663-7030 | ISSN-L: 2616-955X Abdul Qadir Mushtaq* Muhammad Shabbir† Zil-e-Huma Rafique‡ This research narrates Sufi institution’s influence on the religious, political and cultural system. The masses Abstract frequently visit Sufi shrines and perform different rituals. The shrines of Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi of Sial Sharif and Meher Ali Shah of Golra Sharif have been taken as case study due to their religious importance. It is a common perception that people practice religion according to their cultural requirements and this paper deals rituals keeping in view cultural practices of the society. It has given new direction to the concept of “cultural dimensions of religious analysis” by Clifford Geertz who says “religion: as a cultural system” i.e. a system of symbols which synthesizes a people’s ethos and explain their words. Eaton and Gilmartin have presented same historical analysis of the shrines of Baba Farid, Taunsa Sharif and Jalalpur Sharif. This research is descriptive and analytical. Primary and secondary sources have been consulted. Key Words: Khanqah, Dargah, SajjadaNashin, Culture, Esoteric, Exoteric, Barakah, Introduction Sial Sharif is situated in Sargodha region (in the center of Sargodha- Jhang road). It is famous due to Khawaja Shams-Ud-Din Sialvi, a renowned Chishti Sufi.