Understanding State-Level Variations in US Infant Mortality

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

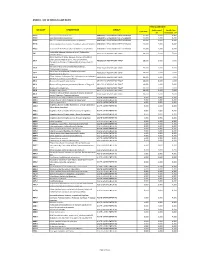

Annex 1: List of Medical Case Rates

ANNEX 1. LIST OF MEDICAL CASE RATES FIRST CASE RATE ICD CODE DESCRIPTION GROUP Professional Health Care Case Rate Fee Institution Fee P91.3 Neonatal cerebral irritability ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.4 Neonatal cerebral depression ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.6 Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy of newborn ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.8 Other specified disturbances of cerebral status of newborn ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.9 Disturbance of cerebral status of newborn, unspecified ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 Peritonsillar abscess; Abscess of tonsil; Peritonsillar J36 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 cellulitis; Quinsy Other diseases of larynx; Abscess of larynx; Cellulitis of larynx; Disease NOS of larynx; Necrosis of larynx; J38.7 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Pachyderma of larynx; Perichondritis of larynx; Ulcer of larynx Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess; J39.0 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Peripharyngeal abscess Other abscess of pharynx; Cellulitis of pharynx; J39.1 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Nasopharyngeal abscess Other diseases of pharynx; Cyst of pharynx or nasopharynx; J39.2 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Oedema of pharynx or nasopharynx J85.1 Abscess of lung with pneumonia ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 J85.2 Abscess of lung without pneumonia; Abscess of lung NOS ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY -

Ten Leading Causes of Death by Age Group,Race/Ethnicity, and Gender

Ten Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, Race/Ethnicity, and Gender Suburban Cook County 2006-2008 Suggested Citation: Cook County Department of Public Health. (2013). Ten Leading Causes of Death Tables 2008. Oak Forest, IL: Community Epidemiology and Health Planning Unit Table of Contents All Suburban Cook County: All Deaths By Gender: Females Males By Race/Ethnicity and Gender: Hispanic Hispanic Females Hispanic Males Non Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander Non Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander Females Non Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander Males Non Hispanic Black Non Hispanic Black Females Non Hispanic Black Males Non Hispanic White Non Hispanic White Females Non Hispanic White Males By District: Cook County Department of Public Health Jurisdiction North District West District Southwest District South District Resources: District Map Rankable Causes of Death Rankable Causes of Infant Death 10 Leading Causes of Death by Age Group, Suburban Cook County, 2006-2008 (Counts/Percent of Total Deaths) All Deaths Rank <1 1-4 5-17 18-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65+ Total Unintentional Unintentional Unintentional Unintentional Malignant Malignant Malignant Short Gestation Heart Disease Heart Disease 1 Injury Injury Injury Injury Neoplasms Neoplasms Neoplasms 170 24.9% 24 23.8% 57 24.6% 196 37.0% 281 34.4% 300 19.2% 1,251 31.7% 2,489 38.9% 13,422 28.2% 16,345 26.4% Congenital Congenital Unintentional Malignant Malignant Homicide Homicide Homicide Heart Disease Heart Disease 2 Anomalies Anomalies Injury Neoplasms Neoplasms 127 18.6% 9 8.9% 44 19.0% 135 -

Helping Mothers Defend Their Decision to Breastfeed

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2015 Helping Mothers Defend their Decision to Breastfeed Kandis Natoli University of Central Florida Part of the Nursing Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Doctoral Dissertation (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Natoli, Kandis, "Helping Mothers Defend their Decision to Breastfeed" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 1392. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/1392 HELPING MOTHERS DEFEND THEIR DECISION TO BREASTFEED by KANDIS M. NATOLI M.S.N. University of Central Florida, 2006 B.S.N. University of Central Florida, 2005 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing in the College of Nursing at the University of Central Florida Orlando Florida Fall Term 2015 Major Professor: Karen Arioan © 2015 Kandis M. Natoli ii ABSTRACT The United States has established breastfeeding as an important health indicator within the Healthy People agenda. Healthy People target goals for breastfeeding initiation, duration, and exclusivity remain unmet. The US Surgeon General’s Office reports that lack of knowledge and widespread misinformation about breastfeeding are barriers to meeting Healthy People goals. Breastfeeding mothers are vulnerable to messages that cast doubt on their ability to breastfeed. Very little research has examined specific approaches to help people resist negative messages about health beliefs and behaviors. -

XI. COMPLICATIONS of PREGNANCY, Childbffith and the PUERPERIUM 630 Hydatidiform Mole Trophoblastic Disease NOS Vesicular Mole Ex

XI. COMPLICATIONS OF PREGNANCY, CHILDBffiTH AND THE PUERPERIUM PREGNANCY WITH ABORTIVE OUTCOME (630-639) 630 Hydatidiform mole Trophoblastic disease NOS Vesicular mole Excludes: chorionepithelioma (181) 631 Other abnormal product of conception Blighted ovum Mole: NOS carneous fleshy Excludes: with mention of conditions in 630 (630) 632 Missed abortion Early fetal death with retention of dead fetus Retained products of conception, not following spontaneous or induced abortion or delivery Excludes: failed induced abortion (638) missed delivery (656.4) with abnormal product of conception (630, 631) 633 Ectopic pregnancy Includes: ruptured ectopic pregnancy 633.0 Abdominal pregnancy 633.1 Tubalpregnancy Fallopian pregnancy Rupture of (fallopian) tube due to pregnancy Tubal abortion 633.2 Ovarian pregnancy 633.8 Other ectopic pregnancy Pregnancy: Pregnancy: cervical intraligamentous combined mesometric cornual mural - 355- 356 TABULAR LIST 633.9 Unspecified The following fourth-digit subdivisions are for use with categories 634-638: .0 Complicated by genital tract and pelvic infection [any condition listed in 639.0] .1 Complicated by delayed or excessive haemorrhage [any condition listed in 639.1] .2 Complicated by damage to pelvic organs and tissues [any condi- tion listed in 639.2] .3 Complicated by renal failure [any condition listed in 639.3] .4 Complicated by metabolic disorder [any condition listed in 639.4] .5 Complicated by shock [any condition listed in 639.5] .6 Complicated by embolism [any condition listed in 639.6] .7 With other -

Glossary of Icd-10 Codes

glossary of icd-10 codes List of 113 Causes of Death (1999-present) Cause of Death ICD-10 Codes Salmonella infections A01-A02 Shigellosis and amebiasis A03, A06 Certain other intestinal infections A04, A07-A09 Tuberculosis A16-A19 Respiratory Tuberculosis A16 Other Tuberculosis A17-A19 Whooping cough A37 Scarlet fever and erysipelas A38, A46 Meningococcal infection A39 Septicemia A40-A41 Syphilis A50-A53 Acute poliomyelitis A80 Arthropod-borne viral encephalitis A83-A84, A85.2 Measles B05 Viral Hepatitis B15-B19 Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease B20-B24 Malaria B50-B54 Other and unspecified infections and parasitic diseases and their sequelae A00, A05, A20-A36, A42-A44, A48-A49, A54-A79, A81-A82, A85.0-A85.1, A85.8, A86-B04, B06-B09, B25-B49, B55-B99 Malignant neoplasm C00-C97 Malignant neoplasm of lip, oral cavity and pharynx C00-C14 Malignant neoplasm of esophagus C15 Malignant neoplasm of stomach C16 Malignant neoplasm of colon, rectum, anus C18-C21 Malignant neoplasm of liver and intrahepatic bile ducts C22 Malignant neoplasm of pancreas C25 Malignant neoplasm of larynx C32 Malignant neoplasm of trachea, bronchus and lung C33-C34 Malignant melanoma of skin C43 Malignant neoplasm of breast C50 Malignant neoplasm of cervix uteri C53 Malignant neoplasm of corpus uteri and uterus, part unspecified C54-C55 Malignant neoplasm of ovary C56 Malignant neoplasm of prostate C61 Malignant neoplasm of kidney and renal pelvis C64-C65 Malignant neoplasm of bladder C67 Malignant neoplasm of meninges, brain, and other parts of central nervous -

Meningitis, Encephalitis and Neonatal Sepsis 1 GBD 2017 1 WHO

The global burden of meningitis in children: Challenges with interpreting global health estimates Supplementary Appendix Contents Mortality modelling methods – Meningitis, encephalitis and neonatal sepsis 1 GBD 2017 1 WHO-MCEE 2000-2017 3 Pathogen specific meningitis mortality and incidence modelling methods 4 GBD 2017 4 MCEE/JHSPH 5 Tables and Figures Table S1: ICD10 codes mapped to meningitis, encephalitis and neonatal sepsis according to model 7 Table S2: Definitions of IHME’s GBD 2017 data quality star rating 12 Table S3: Location level covariates according to model 13 Table S4: Covariates used in WHO-MCEE’s multinomial logistic regression by age group, model and cause 14 Table S5: MCEE Final cause of death list 15 Table S6: MCEE modelled cause of death categories according to age 16 Figure S1: Quality of underlying cause of death data and modelling methods used to generate death estimates according to model. 17 Mortality modelling methods – Meningitis, encephalitis and neonatal sepsis This section provides a brief overview on how the different models derive meningitis, encephalitis and neonatal sepsis mortality estimates. However, full methodology is provided by the modellers elsewhere. Both GBD 2017 and MCEE 2000-2017 models used cause of death data from vital registration (VR) systems, sample registration systems (SR) and verbal autopsy (VA) studies to assign causes of death ensuring that the total number of deaths matches other estimates for the age-specific all-cause mortality. This involves the generation of data where data are The global burden of meningitis in children: Challenges with interpreting global health estimates Supplementary Appendix incomplete or completely missing. -

Transthoracic Echocardiography in Children – (0523)

Medical Coverage Policy Effective Date ............................................02/15/2021 Next Review Date ......................................02/15/2022 Coverage Policy Number .................................. 0523 Transthoracic Echocardiography in Children Table of Contents Related Coverage Resources Overview .............................................................. 1 eviCore Pediatric Cardiac Imaging Guideline Coverage Policy ................................................... 1 Transthoracic Echocardiography in Adults General Background ............................................ 6 Medicare Coverage Determinations .................. 24 Coding/Billing Information .................................. 24 References ........................................................ 61 INSTRUCTIONS FOR USE The following Coverage Policy applies to health benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Certain Cigna Companies and/or lines of business only provide utilization review services to clients and do not make coverage determinations. References to standard benefit plan language and coverage determinations do not apply to those clients. Coverage Policies are intended to provide guidance in interpreting certain standard benefit plans administered by Cigna Companies. Please note, the terms of a customer’s particular benefit plan document [Group Service Agreement, Evidence of Coverage, Certificate of Coverage, Summary Plan Description (SPD) or similar plan document] may differ significantly from the standard benefit plans upon which -

Definitions for Health Care Quality Indicators 2016-2017 HCQI Data Collection

Definitions for Health Care Quality Indicators 2016-2017 HCQI Data Collection 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................................................ 2 GLOSSARY .................................................................................................................................................... 3 DEFINITIONS BY AREA OF WORK AND INDICATOR .......................................................................... 4 PRIMARY CARE ........................................................................................................................................ 5 PRESCRIBING IN PRIMARY CARE ..................................................................................................... 18 ACUTE CARE .......................................................................................................................................... 20 PATIENT SAFETY ................................................................................................................................... 23 MENTAL HEALTH CARE ...................................................................................................................... 42 CANCER CARE ...................................................................................................................................... 425 PATIENT EXPERIENCES ....................................................................................................................... 46 APPENDIX A -

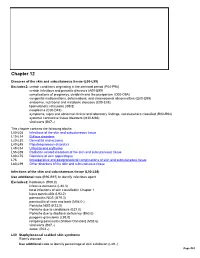

ICD-10-CM TABULAR LIST of DISEASES and INJURIES

K95.09 Other complications of gastric band procedure Use additional code, if applicable, to further specify complication K95.8 Complications of other bariatric procedure Excludes1: complications of gastric band surgery (K95.0-) K95.81 Infection due to other bariatric procedure Use additional code to specify type of infection or organism, such as: bacterial and viral infectious agents (B95.-, B96.-) cellulitis of abdominal wall (L03.311) sepsis (A40.-, A41.-) K95.89 Other complications of other bariatric procedure Use additional code, if applicable, to further specify complication Chapter 12 Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (L00-L99) Excludes2: certain conditions originating in the perinatal period (P04-P96) certain infectious and parasitic diseases (A00-B99) complications of pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium (O00-O9A) congenital malformations, deformations, and chromosomal abnormalities (Q00-Q99) endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (E00-E88) lipomelanotic reticulosis (I89.8) neoplasms (C00-D49) symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R00-R94) systemic connective tissue disorders (M30-M36) viral warts (B07.-) This chapter contains the following blocks: L00-L08 Infections of the skin and subcutaneous tissue L10-L14 Bullous disorders L20-L30 Dermatitis and eczema L40-L45 Papulosquamous disorders L49-L54 Urticaria and erythema L55-L59 Radiation-related disorders of the skin and subcutaneous tissue L60-L75 Disorders of skin appendages L76 Intraoperative and postprocedural -

Synergism Between the Mapping Projects from SNOMED CT to ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM

Synergism between the Mapping Projects from SNOMED CT to ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM Kin Wah Fung 1, MD, MS, MA; Junchuan Xu 2, MD, MS 1National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD 2Lockheed Martin Corporation, Bethesda, MD [email protected]|[email protected] Abstract Two mapping projects are currently underway, creating maps from SNOMED CT to ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM re- spectively. Even though the two projects belong to different organizations, there has been a lot of synergism between them. The ICD-10-CM map project heavily re-used the mapping methodology, tools and map data developed in the ICD-10 map project. An algorithm was derived to generate candidate ICD-10-CM map records from the ICD-10 map. We evaluated the algorithm in 5,264 SNOMED CT concepts common to both maps. 4,317 ICD-10-CM candi- date maps could be generated from the ICD-10 map and 3,341 (77%) of the generated maps agreed with the pub- lished map. By priming the mapping process with candidate maps generated from the other map project, significant saving in time and effort in future phases of the two projects can be anticipated. The reasons for the discordance between the generated map and published map were also analyzed. Introduction The need for mapping between controlled terminologies arises commonly to enable the re-use of data encoded in one terminology for another purpose that requires a different encoding system – the “code once, use multiple times” principle. 1-5 A myriad of medical terminologies exist with varying degree of overlap in their scope of coverage. -

Definitions of Medicare Code Edits

Medicare Code Editor Definitions of Medicare Code Edits v31.0 October 2013 PBL-011 October 2013 Table of Contents About this document .......................................................................................... v Chapter 1: Edit code lists .............................................................................. 7 1. Invalid diagnosis or procedure code ...................................................................................... 7 2. E-code as principal diagnosis ................................................................................................ 7 3. Duplicate of PDX ................................................................................................................... 8 4. Age conflict ............................................................................................................................ 8 Newborn diagnoses ............................................................................................................ 8 Pediatric diagnoses (age 0 through 17) ............................................................................ 13 Maternity diagnoses (age 12 through 55) ......................................................................... 14 Adult diagnoses (age 15 through 124) .............................................................................. 34 5. Sex conflict .......................................................................................................................... 36 Diagnoses for females only .............................................................................................. -

C:\Projects\Bulletin\Bul2010\Intro and Appendices\CONTENTS.10.Wpd

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION Description of Bulletin.....................................................1 Definitions of Live Birth, Fetal Death, Induced Termination, and Death ...............1 Occurrence and Residence Allocation ........................................2 Population ..............................................................2 Race ..................................................................3 Rates..................................................................3 Classification of Cause of Death.............................................3 SUMMARY TABLES, 2010 POPULATION Table P1. 2010 Census Population, by Age, Race, and Sex, Residents of Mississippi..............................................7 LIVE BIRTHS Table A1. Live Births and Average per Day, by Month .......................8 Table A2. Percentage of Live Births in Hospitals or Clinics, by Year and Race, 1940, 1950, 1960, 1970-2010 ...............................8 Table A3. Live Births and Percentage Distribution, by Place of Delivery, Attendant, and Race of Mother ..............................9 Table A4. Live Births, Percentage Distribution, and Fertility Rates, by Age and Race of Mother.........................................10 Table A5. Live Births and Percentage Distribution, by Years of School Completed by Mother and Race of Mother ....................10 Table A6. Live Births to Unmarried Mothers and Percent of Total Live Births in Specified Group, by Age and Race of Mother .................11 Table A7. Live Births, Percentage Distribution,