Helping Mothers Defend Their Decision to Breastfeed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hypocalcemia Associated with Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn: Case Report and Literature Review Alphonsus N

case report Oman Medical Journal [2017], Vol. 32, No. 6: Hypocalcemia Associated with Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn: Case Report and Literature Review Alphonsus N. Onyiriuka 1* and Theodora E. Utomi2 1Endocrine and Metabolic Unit, Department of Child Health, University of Benin Teaching Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria 2Special Care Baby Unit, Department of Nursing Services, St Philomena Catholic Hospital, Benin City, Nigeria ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn (SCFNN) is a rare benign inflammatory Received: 4 November 2015 disorder of the adipose tissue but may be complicated by hypercalcemia or less frequently, Accepted: 21 October 2016 hypocalcemia, resulting in morbidity and mortality. Here we report the case of a neonate Online: with subcutaneous fat necrosis who surprisingly developed hypocalcemia instead DOI 10.5001/omj.2017.99 of hypercalcemia. A full-term female neonate was delivered by emergency cesarean section for fetal distress and was subsequently admitted to the Special Care Baby Keywords: Hypocalcemia; Infant, Unit. The mother’s pregnancy was uncomplicated up to delivery. Her anthropometric Newborn; Subcutaneous Fat measurements were birth weight 4.1 kg (95th percentile), length 50 cm (50th percentile), Necrosis; Perinatal Stress. and head circumference 34.5 cm (50th percentile). The Apgar scores were 2, 3, and 8 at 1, 5, 10 minutes, respectively. There was no abnormal facies and she was fed with breast milk only. On the seventh day of life, the infant was found to have multiple nodules located in the neck, upper back, and right arm. The nodules were firm, well circumscribed with no evidence of tenderness. -

N35.12 Postinfective Urethral Stricture, NEC, Female N35.811 Other

N35.12 Postinfective urethral stricture, NEC, female N35.811 Other urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.812 Other urethral bulbous stricture, male N35.813 Other membranous urethral stricture, male N35.814 Other anterior urethral stricture, male, anterior N35.816 Other urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.819 Other urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.82 Other urethral stricture, female N35.911 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, meatal N35.912 Unspecified bulbous urethral stricture, male N35.913 Unspecified membranous urethral stricture, male N35.914 Unspecified anterior urethral stricture, male N35.916 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, overlapping sites N35.919 Unspecified urethral stricture, male, unspecified site N35.92 Unspecified urethral stricture, female N36.0 Urethral fistula N36.1 Urethral diverticulum N36.2 Urethral caruncle N36.41 Hypermobility of urethra N36.42 Intrinsic sphincter deficiency (ISD) N36.43 Combined hypermobility of urethra and intrns sphincter defic N36.44 Muscular disorders of urethra N36.5 Urethral false passage N36.8 Other specified disorders of urethra N36.9 Urethral disorder, unspecified N37 Urethral disorders in diseases classified elsewhere N39.0 Urinary tract infection, site not specified N39.3 Stress incontinence (female) (male) N39.41 Urge incontinence N39.42 Incontinence without sensory awareness N39.43 Post-void dribbling N39.44 Nocturnal enuresis N39.45 Continuous leakage N39.46 Mixed incontinence N39.490 Overflow incontinence N39.491 Coital incontinence N39.492 Postural -

Disseminated Eosinophilic Infiltration of a Newborn Infant, with Perforation of the Terminal Ileum and Bile Duct Obstruction

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.56.1.66 on 1 January 1981. Downloaded from 66 Shinozaki, Saito, and Shiraki infant who acquired hepatitis from her mother. Br Med J 6 Yoshida A, Tozawa M, Furukawa N, Oya N, Kusunoki T, 1970; iv: 719-21. Kiyosawa N. HBsAg-positive chronic active hepatitis in 3 Bancroft W H, Warkel R L, Talbert A A, Russell P K. a 1 and 1/2 year-old-child (in Japanese). Shonika Shinryo Family with hepatitis-associated antigen. JAMA 1971; 1977;40: 1246-50. 217:1817-20. McCarthy J W. Hepatitis B antigen (HBAg)-positive chronic aggressive hepatitis and cirrhosis in an 8-month- Correspondence to Dr T Shinozaki, Department of old infant. A case report. JPediatr 1973; 83: 638-9. Paediatrics, Teikyo University School of Medicine, 11-1 5 Fujiwara T, Abe M, Tachi N, Jo M, Shiroda M. Kaga, 2 Chome, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo 173, Japan. HBsAg-positive infantile hepatitis associated with chronic aggressive hepatitis (in Japanese). Shonika Rinsho 1975; 28:1303-6. Received 26 November 1979 Disseminated eosinophilic infiltration of a newborn infant, with perforation of the terminal ileum and bile duct obstruction S M MURRAY AND C J WOODS Department ofPathology and Department ofPaediatrics, Victoria Hospital, Blackpool Case report SUMMARY A preterm boy died 4 days after delivery from septicaemia which at necropsy was found to be A white boy, weighing 1490 g, was born by spon- due to perforation of an eosinophilic lesion of the taneous vertex delivery at 35 weeks' gestation to a copyright. terminal ileum. -

Low-Lying Placenta

LOW- LYING PLACENTA LOW-LYING PLACENTA WHAT IS PLACENTA PRAEVIA? The placenta develops along with the baby in the uterus (womb) during pregnancy. It connects the baby with the mother’s blood system and provides the baby with its source of oxygen and nourishment. The placenta is delivered after the baby and is also called the afterbirth. In some women the placenta attaches low in the uterus and may be near, or cover a part, or lie over the cervix (entrance to the womb). If it is shown in early ultrasound scans, it is called a low-lying placenta. In most cases, the placenta moves upwards as the uterus enlarges. For some women the placenta continues to lie in the lower part of the uterus in the last months of pregnancy. This condition is known as placenta praevia. If the placenta covers the cervix, this is known as major placenta praevia. Normal Placenta Placenta Praevia Major Placenta Praevia WHAT ARE THE RISKS TO MY BABY AND ME? When the placenta is in the lower part of the womb, there is a risk that you may bleed in the second half of pregnancy. Bleeding from placenta praevia can be heavy, and so put the life of the mother and baby at risk. However, deaths from placenta praevia are rare. You are more likely to need a caesarean section because the placenta is in the way of your baby being born. HOW IS PLACENTA PRAEVIA DIAGNOSED? A low-lying placenta may be suspected during the routine 20-week ultrasound scan. Most women who have a low-lying placenta at the routine 20-week scan will not go on to have a low-lying placenta later in the pregnancy – only 1 in 10 go on to have a placenta praevia. -

Antepartum Haemorrhage

OBSTETRICS AND GYNAECOLOGY CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE Antepartum haemorrhage Scope (Staff): WNHS Obstetrics and Gynaecology Directorate staff Scope (Area): Obstetrics and Gynaecology Directorate clinical areas at KEMH, OPH and home visiting (e.g. Community Midwifery Program) This document should be read in conjunction with this Disclaimer Contents Initial management: MFAU APH QRG ................................................. 2 Subsequent management of APH: QRG ............................................. 5 Management of an APH ........................................................................ 7 Key points ............................................................................................................... 7 Background information .......................................................................................... 7 Causes of APH ....................................................................................................... 7 Defining the severity of an APH .............................................................................. 8 Initial assessment ................................................................................................... 8 Emergency management ........................................................................................ 9 Maternal well-being ................................................................................................. 9 History taking ....................................................................................................... -

A STUDY of RICKETS; Incidence in London

Arch Dis Child: first published as 10.1136/adc.61.10.939 on 1 October 1986. Downloaded from Archives of Disease in Childhood, 1986, 61, 939-940 A STUDY OF RICKETS; Incidence in London. BY DONALD PATERSON, M.B. (Edin.), M.R.C.P. (London), AND RUTH DARBY, M.B., Ch.B. (Birm.). (From the Infants' Hospital, Westminster.) In order to ascertain the incidence of rickets in London a study was attempted during the months of February, MIarch and April of 1925. It was thought that these being the darkest months of the year, following on a long, sunless period, the incidence of rickets would be at its height. Our fir-st difficulty was to define the basis upon which rickets could be diagnosed. We had over and over again diagnosed rickets clinically . Commentary copyright. J 0 FORFAR The Archives of Disease in Childhood, although it radiologically and 110 (32%) showed evidence of became the official journal of the British Paediatric previous rickets clinically, although radiologically Association (BPA), was first published two years the rickets was shown to have healed. No evidence before the founding of the BPA. Appropriately, the of rickets either clinically or radiologically was senior author of this paper on rickets, Dr Donald found in 225 (67%). Interestingly from a social point Paterson, played a leading part in the founding of of view, another paper in the same issue of the the BPA and was its first Secretary. He was a Archives (by Drs W P T Atkinson, Helen Mackay, http://adc.bmj.com/ Canadian who came to Edinburgh University to W L Kinnear, and H L Shaw) showed that children study medicine. -

Recode - Guidelines for Use the System Is Hierarchical I.E

ReCoDe - Guidelines for use The system is hierarchical i.e. categories at the head of the list take priority over those lower down. However multiple relevant conditions can be recorded. The primary condition is the highest on the list that is applicable to the case. Secondary condition is the next relevant condition down the list e.g. for codes B2, F3, and A7 - the primary code is A7, secondary code is B2 etc. ReCoDe - version 2.0 Group Condition further definition inclusion/exclusion A Fetus A1 Lethal congenital anomaly Lethal or severe. Any structural, genetic, or metabolic defect arising at conception or during embryogenesis incompatible with life or potentially treatable but causing death. A2 Infection Positive fetal microbiologic or serological culture. 2.1 Chronic – e.g. TORCH E.g. congenital or intrauterine pneumonia, cytomegalovirus, 2.2 Acute rubella, herpes. A3 Non-immune hydrops fetalis Presence of any two of the following signs: Ascites pericardial effusion pleural effusion subcutaneous oedema. A4 Iso-immunisation Blood group incompatibility rhesus or non rhesus (ABO). Death ascribable to blood group incompatibility. An indirect Coomb test greater than 1/16 and fetal hydrops (see A3). A5 Fetomaternal haemorrhage Haemorrhage into maternal circulation Kleihauer-Betke test > 0.4%1. A6 Twin-twin transfusion Presence of polyhydramnios (maximum vertical pocket of ≥ 8 cm) and oligohydramnios (maximum vertical pocket of ≤ 2 cm)2. A7 Fetal growth restriction SGA by customised percentile, intrauterine growth retardation. < 10th customised weight for gestational age centile3 OR IUGR reported on clinical or pathological grounds. A8 Other fetus Death due to other specific fetal conditions e.g. -

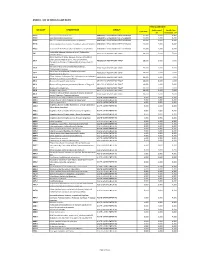

Annex 1: List of Medical Case Rates

ANNEX 1. LIST OF MEDICAL CASE RATES FIRST CASE RATE ICD CODE DESCRIPTION GROUP Professional Health Care Case Rate Fee Institution Fee P91.3 Neonatal cerebral irritability ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.4 Neonatal cerebral depression ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.6 Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy of newborn ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.8 Other specified disturbances of cerebral status of newborn ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 P91.9 Disturbance of cerebral status of newborn, unspecified ABNORMAL SENSORIUM IN THE NEWBORN 12,000 3,600 8,400 Peritonsillar abscess; Abscess of tonsil; Peritonsillar J36 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 cellulitis; Quinsy Other diseases of larynx; Abscess of larynx; Cellulitis of larynx; Disease NOS of larynx; Necrosis of larynx; J38.7 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Pachyderma of larynx; Perichondritis of larynx; Ulcer of larynx Retropharyngeal and parapharyngeal abscess; J39.0 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Peripharyngeal abscess Other abscess of pharynx; Cellulitis of pharynx; J39.1 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Nasopharyngeal abscess Other diseases of pharynx; Cyst of pharynx or nasopharynx; J39.2 ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 Oedema of pharynx or nasopharynx J85.1 Abscess of lung with pneumonia ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY TRACT 10,000 3,000 7,000 J85.2 Abscess of lung without pneumonia; Abscess of lung NOS ABSCESS OF RESPIRATORY -

Sclerema Neonatorum Treated with Intravenous Immunoglobulin: a Case Report and Review of Treatments

Sclerema Neonatorum Treated With Intravenous Immunoglobulin: A Case Report and Review of Treatments Kesha J. Buster, MD; Holly N. Burford, MD; Faith A. Stewart, MD; Klaus Sellheyer, MD; Lauren C. Hughey, MD Practice Points Sclerema neonatorum is a rare neonatal panniculitis with a high mortality rate. Exchange transfusion improves survival, but its use in neonates has declined. Intravenous immunoglobulin represents a novel treatment option that may lead to increased survival in pre- term newborns with sclerema neonatorum. Sclerema neonatorum (SN)CUTIS is a rare neonatal improvement. Sclerema neonatorum remains a panniculitis that typically develops in severely poorly understood and difficult to treat neona- ill, preterm newborns within the first week of tal disorder. Although IVIG did not prevent our life and often is fatal. It usually occurs in pre- patient’s death, further studies are needed to term newborns with delivery complications such determine its clinical utility in the treatment of this as respiratory distress or maternal complica- rare disorder. tions such as eclampsia. Few clinical trials have Cutis. 2013;92:83-87. beenDo performed to address Notpotential treatments. Copy Successful treatment has been achieved via exchange transfusion (ET), but its use in neonates clerema neonatorum (SN) is a rare neonatal is declining. Similar to ET, intravenous immuno- panniculitis that typically develops in severely globulin (IVIG) enhances both humoral and Sill, preterm newborns within the first week cellular immunity and thus may decrease mor- of life. It is characterized by rapidly progressive tality associated with SN. We report a case of induration of subcutaneous fat. Treatments include SN in a term newborn who subsequently devel- supportive care, emollients, warming/maintaining oped septicemia. -

Umbilical Cord Accidents

UMBILICAL CORD ACCIDENTS DR PADMASRI R PROF & HOD, DEPT OF OBSTETRICS & GYNAECOLOGY SAPTHAGIRI INSTITUTE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES 1 • “Cord accident,” defined by obstruction of fetal blood flow through the umbilical cord, is a common ante- or perinatal occurrence. • Obstruction can be either acute, as in cases of cord prolapse during delivery, or sub acute to-chronic, as in cases of grossly abnormal umbilical cords Placental findings in cord accidents. Mana M Parast From Stillbirth Summit 2011, Minneapolis, USA 2 TYPES Acute events Sub Acute on Chronic • Umbilical Cord Prolapse • Loops • Knots • Vasa Praevia • Entanglements • Coiling • Torsion • Rupture • Haematomas, thrombosis • Cysts, tumours • Nuchal Cord • Insertion - velamentous cord CORD COMPRESSION – SUDDEN IUD’s 3 CORD COMPRESSION 2 Principles of asphyxia are: a. Cord compression -preventing venous return to the fetus b. Umbilical vasospasm -preventing venous and arterial blood flow to and from the fetus due to exposure to external environment. 4 Recovery time from compression • 1min, 1 time 100% compression – 5 mins to recover- oxygen levels decrease by 50% • 5 mins comp – 30 mins to recover • Continued 5 min compressions every 30 mins causes fetal decompensation RISK FACTORS FOR CORD PROLAPSE GENERAL PROCEDURE RELATED Artificial rupture of membranes with high Multiparity presenting part Vaginal manipulation of the fetus with ruptured Low birthweight (< 2.5 kg) membranes Preterm labour (< 37+0 External cephalic version (during procedure) weeks) Fetal congenital anomalies Internal podalic version Breech presentation Stabilising induction of labour Transverse, oblique and Insertion of intrauterine pressure transducer unstable lie* Second twin Large balloon catheter induction of labour Polyhydramnios Unengaged presenting part Low-lying placenta RCOG Green-top Guideline No. -

Perinatal Arterial Ischemic Stroke: an Unusual Causal Mechanism

ical C lin as C e f R o l e Russo et al., J Clin Case Rep 2014, 4:8 a p n o r r u t DOI: 10.4172/2165-7920.1000401 s o J Journal of Clinical Case Reports ISSN: 2165-7920 Case Report Open Access Perinatal Arterial Ischemic Stroke: An Unusual Causal Mechanism Francesca Maria Russo1*, Giuseppe Paterlini2 and Patrizia Vergani1 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy 2Department of Pediatrics and Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, University of Milano-Bicocca, Monza, Italy Abstract Perinatal Arterial Ischemic Stroke (AIS) is an important cause of neurological morbidity in infants. Some risk factors have been identified, but its pathogenesis remains unclear. We present a case of perinatal in which macroscopic examination of the placenta revealed the presence of a vasa praevia. We hypothesize that compression of the vasa praevia during labor could have determined the formation of thrombi, which were subsequently embolized into the fetal circulation causing perinatal AIS. Background increased flow in the districts of the sylvian artery. No cardiac anatomic or functional abnormalities were found. Coagulation studies were Perinatal arterial ischemic stroke (AIS) is estimated to occur in the normal range and disorders of the coagulation pathway were in 1/1600 to 1/5000 births [1]. Even if rare, it is an important cause excluded. Thrombophilias were excluded both in the baby and in the of mortality and morbidity in neonates. A meta-analysis showed mother. that 57% of infants who suffer perinatal AIS develop motor and/or cognitive deficits, and 3% die [2]. -

The Identification and Validation of Neural Tube Defects in the General Practice Research Database

THE IDENTIFICATION AND VALIDATION OF NEURAL TUBE DEFECTS IN THE GENERAL PRACTICE RESEARCH DATABASE Scott T. Devine A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Public Health (Epidemiology). Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by Advisor: Suzanne West Reader: Elizabeth Andrews Reader: Patricia Tennis Reader: John Thorp Reader: Andrew Olshan © 2007 Scott T Devine ALL RIGHTS RESERVED - ii- ABSTRACT Scott T. Devine The Identification And Validation Of Neural Tube Defects In The General Practice Research Database (Under the direction of Dr. Suzanne West) Background: Our objectives were to develop an algorithm for the identification of pregnancies in the General Practice Research Database (GPRD) that could be used to study birth outcomes and pregnancy and to determine if the GPRD could be used to identify cases of neural tube defects (NTDs). Methods: We constructed a pregnancy identification algorithm to identify pregnancies in 15 to 45 year old women between January 1, 1987 and September 14, 2004. The algorithm was evaluated for accuracy through a series of alternate analyses and reviews of electronic records. We then created electronic case definitions of anencephaly, encephalocele, meningocele and spina bifida and used them to identify potential NTD cases. We validated cases by querying general practitioners (GPs) via questionnaire. Results: We analyzed 98,922,326 records from 980,474 individuals and identified 255,400 women who had a total of 374,878 pregnancies. There were 271,613 full-term live births, 2,106 pre- or post-term births, 1,191 multi-fetus deliveries, 55,614 spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, 43,264 elective terminations, 7 stillbirths in combination with a live birth, and 1,083 stillbirths or fetal deaths.