Chapter III Factors Contributing to the Formation of Progressive Writers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fatal Flame

pT Lit 003 Rakhshanda Jalil’s translation of Gulzar’s short story Dhuaan wins the inaugural Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-English translation The fatal flame alpix 0761 Dr Rakhshanda Jalil Publisher : Hachette UK BA Eng Hons 1984 MH MA Eng 1986 LSR Writer Late last week, it was announced that Delhi-based writer, critic and literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil would be awarded the inaugural Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-english translation, instituted in the memory of Urdu poet and scholar Ali Jawad Zaidi by his family, on the occasion of his birth centenary. A recipient of the Padma Shri, the Ghalib Award and the Mir Anis award, Zaidi had to his name several books of ghazals and nazms, scholarly works on Urdu literature, including The History Of Urdu Literature, and was working on a book called Urdu Mein Ramkatha when he died in 2004. Considering that much of Zaidi’s work “served as a bridge between languages and cultures”, his family felt the best way to honour his literary legacy would be to focus on translations. Since the prize was to be given to a short story in translation in the first year, submissions of an unpublished translation of a published Urdu story were sought. While Jalil won the prize, the joint runners-up were Fatima Rizvi, who teaches literature at the University of Lucknow, and Pakistani social scientist and critic Raza Naeem. The judges, authors Tabish Khair and Musharraf Ali Farooqi, chose to award Jalil for her “careful, and even” translation of a story by Gulzar, Dhuaan (Smoke), “which talks about the violence and tragic absurdity of religious prejudice”. -

A Tribute to Shri A.J. Zaidi

A Tribute to Shri A.J. Zaidi Bal Anand was born in 1943, in a village about 20 km south of Ludhiana, in a family of saint-scholars who practised Ayurveda. Graduated from DAV College, Jalandhar, and did Master in English Literature from Govt. College, Ludhiana. After a stint for a few years as lecturer, joined the Indian Foreign Service. Served in nine different countries and retired as India’s High commissioner to New Zealand. Now reading, reflecting and writing in nest in Delhi, on the East Bank of Yamuna. Bal Anand Having spent my childhood years in a village and later growing up in a town, both located in the closer vicinity of Malerkotla, the only princely state in the East Punjab ruled for centuries by the Muslim Nawabs, I had started wondering and pondering since long over the harmonies and divides between the Hindus and Muslims. The small state of Malerkotla had remained comparatively immune from the mindless violence during the Partition of the country. I have a vivid memory of an inscription, intact in 1951 but decimated soon after, of the name of Nawab Iftikhar Ali Khan on the front wall of the Gurudwara in Ahmedgarh for his donation of Rs. 500.00 – it must have been a princely sum in those days! I had instinctively developed a faith in the mutual accommodation among faiths long before I was destined to be an Indian diplomat in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Maldives! This is a prologue to my tribute to late Syed Ali Jawad Zaidi (1916-2004), who embodied for me the highest virtues of all the faiths of mankind. -

Bhakti Movement

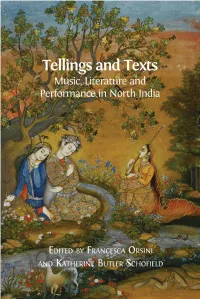

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

Non-Cooperation 1920-1922: Regional Aspects of the All India Mobilization

NON-COOPERATION 1920-1922: REGIONAL ASPECTS OF THE ALL INDIA MOBILIZATION Ph.D Thesis Submitted by: SAKINA ABBAS ZAIDI Under the Supervision of Dr. ROOHI ABIDA AHAMAD, Associate Professor Centre of Advance Study Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh(India) 2016 Acknowledgements I am immensely thankful to ‘Almighty Allah,’ and Ahlulbait (A.S), for the completion of my work in spirit and letter. It is a pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of all my teachers, friends, well-wishers and family with whose help and advice I was able to complete this work, as it is undeniable true that thesis writing involves other aiding you directly or indirectly. First and foremost, beholden to my supervisor, Dr. Roohi Abida Ahmed, for her encouragement, moral support, inspiring suggestions and excellent guidance. The help she extended to me was more than what I deserve. She always provided me with constructive and critical suggestions. I felt extraordinary fortunate with the attentiveness I was shown by her. I indeed consider myself immensely blessed in having someone so kind and supportive as my supervisor from whom I learnt a lot. A statement of thanks here falls very short for the gratitude I have for her mentorship. I gratefully acknowledge my debt to Professor Tariq Ahmed who helped a lot in picking up slips and lapses in the text and who has been a constant source of inspiration for me during the course of my study. I am thankful to Professor Ali Athar, Chairman and Coordinator, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, AMU, Aligarh for being always receptive and supportive. -

A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture, Part 1

ASPECTS OF EARLY URDU LITERARY CULTURE AND HISTORY By Shamsur Rahman Faruqi History, Faith, and Politics Using the term “early Urdu” is not without its risks. “Urdu” as a language name is of comparatively recent origin, and the question of what was or is “early Urdu” has long since passed from the realm of history, first into the colonialist constructions of the history of Urdu/Hindi, and then into the political and emotional space of Indian (=Hindu) identity in modern India. For the average Hindi-user today, it is a matter of faith to believe that the language he knows as “Hindi” is of ancient origin, and its literature originates with K. husrau (1253-1325), if not even earlier. Many such people also believe that the pristine “Hindī” or “Hindvī” became “Urdu” sometime in the eighteenth century, when the Muslims “decided” to veer away from “Hindī” as it existed at that time, and adopted a heavy, Persianised style of language which soon became a distinguishing characteristic of the Muslims of India. In recent times, this case was most elaborately presented by Amrit Rai (Amrit Rai 1984). Rai’s thesis, though full of inconsistencies or tendentious speculation rather than hard facts, and of fanciful interpretation of actual facts, was never refuted by Urdu scholars as it should have been. Quite a bit of the speculation that goes by the name of scholarly historiography of Hindi/Urdu language and literature today owes its existence to the fortuity of nomenclature. Early names for the language now called Urdu were, more or less in this order: 1) Hindvī; 2) Hindī; 3) Dihlavī; 4) Gujrī; 5) Dakanī; and 6) Rek.htah. -

Five Sentimental Scenes

THE MUSLIM LEAGUE IN BARABANKI: A Suite of Five Sentimental Scenes by C. M. Naim Indian Institute of Advanced Study Shimla, 2010 Preface What follows was originally written as two independent essays, at separate times and in reverse order. The first essay was written in 1997, the fiftieth year of Independence in South Asia. It contained the last two scenes. The second, consisting of Scenes 1 through 3, was written in 2006 to mark the 100th year of the formation of the Muslim League. The underlying impulse, confessional and introspective, was the same in both instances. The two essays, with some corrections and changes, are now presented as a single narrative. I am grateful to the Indian Institute of Advanced Study and its Director, Dr. Peter R. deSouza, for making it possible. C. M. Naim, National Fellow, IIAS Shimla October 2009 2 THE MUSLIM LEAGUE IN BARABANKI: A Suite of Five Sentimental Scenes No! I am not Prince Hamlet, nor was meant to be; Am an attendant lord, one that will do To swell a progress, start a scene or two…. (T. S. Eliot, ‘The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.’) (1) In December 1906, twenty-eight men traveled to Dhaka to represent the United Provinces of Agra & Avadh at the foundational meeting of the All India Muslim League. Two were from Barabanki, one of them my granduncle, Raja Naushad Ali Khan of Mailaraigunj. Thirty-nine years later, during the winter of 1945-46, I could be seen, together with other kids, marching up and down the one main road in Barabanki under the green flag of the Muslim League, shouting slogans in support of its candidate in the assembly elections. -

Curriculum Vita

Curriculum Vita Dr. Mohd Rashid Azeez Assistant Professor Department of Urdu, School of languages, Central University of Kashmir Puhroo Chowk, Bypass SRINAGAR – 190015 J&K Cont. No.: +91-8803766036 Office No.: +91-0194-2315271 Email : [email protected] ................................................................................................................................................ Academic Profile I Mohammad Rashid Azeez was born at Hayat Nagar, Sambhal, Moradabad U.P. My father’s name is Mr. Abdus Samad Saifi. I have completed my Matric from Zia ul Uloom Higher Secondary School Sarai Tarin and Intermediate from Hind Inter College Sambhal and B.A. from Dharam Samaj College Aligarh Dr. B.R.A. University and M.A. Urdu from Dr. B.R.A. University Agra and I have qualified the NET exam of UGC as well. I have many courses like Adeeb-e-Mahir and Adeeb-e-Kamil from Jamia Urdu Aligarh and Dabir-e-fazil from Urdu Board Aligarh to my credit. I have also completed basic Computer Course from S.I.E.T. Chandigarh. I have been awarded Ph.D Degree by MJP Rohilkhand University Bareilly under the supervision of Prof. Shahzad Anjum, Government Women’s PG College Rampur. I took PG Diploma in Paleography from University of Delhi. I started my teaching career as Urdu Teacher/ Lecturer in several schools and colleges as Sabri H.S.S. School Chandigarh, Nighat Inter College Sambhal, SBH Azad Girl’s Degree College Sambhal, Urdu Academy Delhi, Satyawati College Delhi and I was associated with the Department of Urdu, University of Delhi and at the same time served as an editor of many magazines and journals including the prestigious Urdu journal quarterly “Naya Safar” Allahabad and Delhi (07 Issues) and one of the most popular Urdu literary magazine Aiwan-e-Urdu Delhi (42 Issues), a children’s magazine “Bachchon ka Mahnama Umang” (42 Issues). -

Faculty Details Proforma for College Web-Site

Faculty details proforma for College Web-site Title First Name Raisa Last Name Parveen Photograph Designation Assistant Professor Address 2818, Street Garahiya Kucha, Challan Darya Ganj New Delhi-110002 Phone No Office 9910139467 Residence 9910139467 Mobile Email [email protected] Web-Page Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D University of Delhi ,Delhi 2007 M.Phil do-----------do------------do M.A (Urdu Literature) do-----------do------------do B.A (Pass) do-----------do------------do Diploma in Translation do----------do-----------do from Urdu to English & Vice Versa B.Lib Science do----------do-----------do 19 UGC Net do----------do-----------do 2001 Career Profile Working as Assistant Professor in the Department of Urdu Satyawati College,University of Delhi, Delhi from 21st July, 2008. Administrative Assignments i) Teacher Incharge for the Academic Session 2015-2016 ii) Teacher Incharge for the Academic Session 2014-2015 iii) Teacher Incharge for the Academic Session 2012-2013 1. Member of Different Committees of the College: i) Member of Selection Committee several times. ii) Member of Admission Committee for the Academic Session 2015-2016 iii) Member of Examination Committee for the Academic Session 2012-2013 iv) Member of Development Committee of Satyawati college. v) Member of Magazine Committee of Satyawati college. vi) Member of Screening Committee of Satyawati college. vii) Member of Academic Journal Committee of Satyawati college viii) Member of Library Committee of Satyawati college.. ix) Member of Photography Society of Satyawati college. x) Member of Art & Culture Society of Satyawati college. xi) Member of Dramatic Society of Satyawati college xii) Member of Student Advisory Committee of Satyawati College of Session 2016-17 xiii) Member of Film Society of Satyawati College of Session 2016-17 2. -

Love at Every Step

My Concept of Poetry The beauty of word and phrase may attract the eye, But O my friend, it is the heart's blood that brings poetry to life. MY PHILOSOPHY OF POETRY is not the child of thought and reflection alone. It is born of life itself. It is, however, not limited to my own experiences. It arises from that limitless ocean of human life which surges around us. My poetry, which I regard as the cry of the soul, is a gift of the two great spiritual luminaries, my divine Master Hazur Baba Sawan Singh Ji Maharaj and my revered father Sant Kirpal Singh Ji Maharaj. I have sought to acknowledge my debt to them in the following words: With every breath I must bow to my Friend, For I owe my life to his grace. If I were to sum up my philosophy as an artist in two words, they would be "fellowship" and "brotherhood." In employing these terms I do not have in mind any "ism" or creed. I am referring to that principle at the root of human nature, which is, in fact, the very foundation and crowning jewel of the universe - the principle of love. If the subject of love were grasped in its fullness, it would be seen to encompass all existence. Let me cite some of my verses on this theme. O Cupbearer, the intoxicating wine you served overflowed the goblet of my heart, And now I am in love with all humanity. Embrace every man as your very own, And shower your love freely wherever you go. -

Curriculum Vitae

BIO-DATA (To be presented in CD) 1. Name : DR. HABIBULLAH 2. Father's Name : Late Samiullah 3. Address (Residential) : B 2/131, Bhadaini, Varanasi 4. Mobile No. : 09452583533 5. Designation : Lecturer 6. Department : Urdu 7. Date of Birth : 07-02-1960 8. Area of Specialization : Urdu Shairi 9. (i) Academic Qualifications Exam Passed Board/University Subjects Year Division/Grade Merit etc. High School U.P. Board Hindi, Eng., 1975 IInd Math, Science, Biology Higher U.P. Board Hindi, Urdu, 1977 IIIrd Secondary or Eng., Pre-degree Economics, History Bachelor's B.H.U. Urdu, Eng., 1979 IInd Degree (s) Economics Master's B.H.U. Urdu 1981 Ist Degree (s) Research B.H.U. Urdu 1987 - Degree (s) Other Diploma Jamia Urdu Urdu 1994 IInd / Moallim-e- Aligarh Urdu Certificates etc. ii) Research Experience & Training Research Stage Title of work/Theses University where the Year work was carried out M.Phil or equivalent Ph.D. Azamgarh aur Urdu B.H.U. 1987 Shairi Post-Doctoral Research Guidance (give names of students guided successfully) Training (please specify) Orientation Course B.H.U. 2008 (Orientation Course/Refresher Course) iii (a) Sl. Title of the Project Name of the Duration Year Remarks No. funding Agency × × × × × × iii (b) Sl. Year Title of the Name of the Duration Remarks No. Project funding Agency Dec.'04 Nil Dec.'05 Nil Dec.'06 Nil Dec.'07 Nil Dec.'08 Nil 10. Teaching Experience a) Under-graduate (Hons) : 3 ½ years b) Post-graduate : NIL Total Teaching Experience : 3 ½ years 11. (a) Total No. of Seminars/Conferences/Workshops etc. -

Rekhti Poetry: Love Between Women (Urdu)

Rekhti Poetry: Love between WOmen (Urdu) Introduced and translated by Saleem Kidwai, versified by Ruth Vanita ckbti is the feminine of Rckbta, which is what Urdu was originally called. But "Rekhti" R usually refers to poetry written by male poets in the female voice and using female idiom in Lucknow in the late·eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Although the poet Rangeen is supposed to have coined the term "Rekhti," the tradition of men writing mystic poetry in the female voice and idiom was well established in the various northern Indian languages and dialects from which Urdu emerged. Many poems attributed to Amir Khusro (see p. 12.9) are devotional poems in the female voice. In the twentieth century Rekhti was labeled obscene and systematically eliminated from the Urdu canon (see pp. 191-94 for an account of this process). Rangeen's poems, translated here, have been selected from the very small body of his work that is available. The two poems that poet Jur' at called cbaptinamas have been excluded from editions of his collected works published in India. Critics exclude Jur' at from their account of the Rekhti poets in order to avoid citing his chaptinamas. In Rekhti recitation at musbairas (poets' gatherings), poets often mimicked the feminine voice to stress the female persona in the poem. Poet Insha assumed different personae while reciting; and Jan Saheb (1817-1896) used a veil as a prop during mushairas. Several poets seem to have dressed as women at nineteenth-century mushairas. 2 Many Rekhti poets also took feminine pen names, including Dogana, one of the terms used in Urdu to refer to homo erotically inclined women. -

Dastan-E Amir Hamza in Text and Performance

Dastan-e Amir Hamza in Text and Performance Shaheen Saba1 “Once upon a time and a very good time it was…” --- James Joyce, A Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man2 The basic meaning of dastan or qissa is a story.3 Dastan-e Amir Hamza is an epic romance which is an amalgam of fantastic adventures, wars, conquests, love and heroic deeds of valour. The supernatural, magic and enchantment are abound. Dastans were narrated by dastangos4 in courts, coffee houses5 and market places. Frances Pritchett asserts that “ i t was a widely popular form of story-telling: dastan-narrators practiced their art not merely in cof f ee houses, but i n royal pal aces as wel l .” Dastangoi is a form of storytelling and also a performative art that was practiced for centuries by practitioners. This paper is an attempt to trace the evolution of dastan and the revival of dastangoi in contemporary times. Dastans were usually orally narrated to audiences in public gatherings or in the royal courts and contributed to be a major form of art and entertainment in medieval and modern India. Similar kinds of performances exist in Arab and Iran (in Iran oral performances called naqqali are done mostly from Ferdowsi’s Shahnamah). It can be traced back to centuries, as early as seventh century when oral narratives of the valour and deeds of Prophet Muhammad’s uncle Amir Hamza travelled through Arabia, Persia and the Indian subcontinent; the expansion of the stories culminated into a marvellous chronicle. There is a difficulty in chronicling the Hamza cycles as also the Arab ones due to its transposition and metamorphosis through time.