Dastan-E Amir Hamza in Text and Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Fatal Flame

pT Lit 003 Rakhshanda Jalil’s translation of Gulzar’s short story Dhuaan wins the inaugural Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-English translation The fatal flame alpix 0761 Dr Rakhshanda Jalil Publisher : Hachette UK BA Eng Hons 1984 MH MA Eng 1986 LSR Writer Late last week, it was announced that Delhi-based writer, critic and literary historian Rakhshanda Jalil would be awarded the inaugural Jawad Memorial Prize for Urdu-english translation, instituted in the memory of Urdu poet and scholar Ali Jawad Zaidi by his family, on the occasion of his birth centenary. A recipient of the Padma Shri, the Ghalib Award and the Mir Anis award, Zaidi had to his name several books of ghazals and nazms, scholarly works on Urdu literature, including The History Of Urdu Literature, and was working on a book called Urdu Mein Ramkatha when he died in 2004. Considering that much of Zaidi’s work “served as a bridge between languages and cultures”, his family felt the best way to honour his literary legacy would be to focus on translations. Since the prize was to be given to a short story in translation in the first year, submissions of an unpublished translation of a published Urdu story were sought. While Jalil won the prize, the joint runners-up were Fatima Rizvi, who teaches literature at the University of Lucknow, and Pakistani social scientist and critic Raza Naeem. The judges, authors Tabish Khair and Musharraf Ali Farooqi, chose to award Jalil for her “careful, and even” translation of a story by Gulzar, Dhuaan (Smoke), “which talks about the violence and tragic absurdity of religious prejudice”. -

History and Heritage, Vol

Proceeding of the International Conference on Archaeology, History and Heritage, Vol. 1, 2019, pp. 1-11 Copyright © 2019 TIIKM ISSN 2651-0243online DOI: https://doi.org/10.17501/26510243.2019.1101 HISTORY AND HERITAGE: EXAMINING THEIR INTERPLAY IN INDIA Swetabja Mallik Department of Ancient Indian History and Culture, University of Calcutta, India Abstract: The study of history tends to get complex day by day. History and Heritage serves as a country's identity and are inextricable from each other. Simply speaking, while 'history' concerns itself with the study of past events of humans; 'heritage' refers to the traditions and buildings inherited by us from the remote past. However, they are not as simple as it seems to be. The question on historical consciousness and subsequently the preservation of heritage, intangible or living, remains a critical issue. There has always remained a major gap between the historians or professional academics on one hand, and the general public on the other hand regarding the understanding of history and importance of heritage structures. This paper tends to examine the nature of laws passed in Indian history right from the Treasure Trove Act of 1878 till AMASR Amendment Bill of 2017 and its effects with respect to heritage management. It also analyses the sites of Sanchi, Bodh Gaya, and Bharhut Stupa in this context. Moreover, the need and role of the museums has to be considered. The truth lies in the fact that artefacts and traditions both display 'connected histories'; and that the workings of archaeology, history, and heritage studies together is responsible for the continuing dialogue between past, present, and future. -

Dastangoi: a Diasporic Culture of Storytelling

DASTANGOI: A DIASPORIC CULTURE OF STORYTELLING ISHRAT JAHAN Ph.D Scholar, Department of English, Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad. (INDIA) In contemporary period, diaspora literature is studied from different perspectives. The emerging interest in diasporic studies has recently begun to permeate various academic disciplines, none more so than cultural studies. Diaspora is a Greek word which was used to refer the dispersion of Jews, migrated from their homeland Israel. In her Critical Dialogues in Cultural Studies, Stuart Hall examined diaspora into different contexts such as ethnicity and identity. In this paper, my study will be focus on Urdu storytelling tradition 'Dastangoi' as diasporic cultural art of story-narrating which was not originated in India but brought by Mughals in 16th century. How this tradition was brought and practised by different people of different communities in each period. In contemporary period, it is being practised by Mahmood Farooqui and his group. Keywords: Dastangoi, Diasporic art, Mahmood Farooqui, Mughals and Storytelling etc. Introduction The word 'Diaspora' is derived from Greek word, means 'scattering' which was used to refer the dispersion of Jews, migrated from their homeland Israel. It is also considered that dispersion of the people from their homeland was not limited with the dispersion of population but it was an expansion of language, culture or tradition. The word 'Diaspora' was recorded in English language in 1876 referring to the Irish migrants. Later in the 1980s and onwards, this term was used metaphorically designation of different migrant people such as expellees, immigrants, Alien residents and political refugees etc. The aim of this paper is to focus on Dastangoi, an Urdu storytelling tradition in the context of diasporic cultural art. -

Indian Culture and Psychology: a Consciousness Perspective” March 22-27, 2018

ANNOUNCEMENT Swadeshi Indology Conference on Mind Sciences “Indian Culture and Psychology: A Consciousness Perspective” March 22-27, 2018 The Department of Psychology, University of Delhi, and Infinity Foundation India are glad to announce a six-day international conference and workshops on Indian Culture and Psychology: A Consciousness Perspective. Some of the themes will include: • Critical Issues in Indian Psychology • Theoretical Models & Applications in Education • Theoretical Models & Applications in Clinical and Counseling Psychology • Theoretical Models & Applications in Organizational Psychology • Research in Indian Psychology: First person, second person, and third person • Toward a shastra for Indian Psychology We propose to invite fifty-four resource persons who are experts in the above- mentioned themes. The goal is to have an intensive dialogue and sustained sharing, and limit attendance to no more than 300 participants. The purpose is to have the participation of students and faculty in Delhi and other Indian cities, to increase their awareness about the efficacy and potential of Indian Psychology. to address both local and global concerns, theoretical and applied. The proceedings will be selectively published. Scholars who are not included in the attached list of invitees, but who have a serious interest to attend, may contact: [email protected] Further details are attached. Registration details are given on last page of attachment. Best regards, Dr. Suneet Varma, Co-Convener Shri Rajiv Malhotra, Co-Convener University of Delhi Infinity Foundation India 1 The present state of psychology as an academic discipline in India Classical Indian Philosophy is rich in psychological content. Our culture has given rise to a variety of practices that have relevance today in areas ranging from stress-reduction to self- realization. -

Dastan-E Amir Hamza in Colonial India

CLRI CONTEMPORARY LITERARY REVIEW INDIA —Brings articulate writings for articulate readers. ISSN 2250-3366 eISSN 2394-6075 SHAHEEN SABA Dastan-e Amir Hamza in colonial India Abstract This paper explores how several factors coupled with the development of printing press in India in the nineteenth century that led to its boom in the Indian subcontinent. Besides the colonial pursuits of the British, the nineteenth century was the age of emergence of Urdu prose mostly centred around religion and ethics. Urdu literature was more poetry-centred than prose. The prose of Urdu literature was mainly restricted to the ancient form of long-epic stories called dastan which stood close to narrative genres in South Asian literatures such as Persian masnawi, Punjabi qissa, Sindhi waqayati bait, etc. Dastan-e- Amir Hamza is considered the most important Indo-Islamic prose epic. Besides Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, there are several other prominent dastans in Urdu. They represent contaminations of wandering and adventure motifs borrowed from the folklore of the Middle East, central Asia and northern India. These include Bostan-e- Khayal, Bagh-o Bahar by Mir Amman, Mazhab-i-Ishq by Nihalchand Lahori, Araish-i-Mahfil by Hyderbakhsh Hyderi, Gulzar-i-Chin by Khalil Ali Khan Ashq, and other offspring of dastans. Vol 4, No 1, CLRI February 2017 54 CLRI CONTEMPORARY LITERARY REVIEW INDIA —Brings articulate writings for articulate readers. ISSN 2250-3366 eISSN 2394-6075 Keywords: Dastan-e Amir Hamza, colonial India, Urdu prose, Urdu poetry, Urdu literature, Persian masnawi, Punjabi qissa, Sindhi waqayati bait. Dastan-e Amir Hamza in colonial India by Shaheen Saba The coming of dastan1 or qissa in India was not an abrupt one. -

A Tribute to Shri A.J. Zaidi

A Tribute to Shri A.J. Zaidi Bal Anand was born in 1943, in a village about 20 km south of Ludhiana, in a family of saint-scholars who practised Ayurveda. Graduated from DAV College, Jalandhar, and did Master in English Literature from Govt. College, Ludhiana. After a stint for a few years as lecturer, joined the Indian Foreign Service. Served in nine different countries and retired as India’s High commissioner to New Zealand. Now reading, reflecting and writing in nest in Delhi, on the East Bank of Yamuna. Bal Anand Having spent my childhood years in a village and later growing up in a town, both located in the closer vicinity of Malerkotla, the only princely state in the East Punjab ruled for centuries by the Muslim Nawabs, I had started wondering and pondering since long over the harmonies and divides between the Hindus and Muslims. The small state of Malerkotla had remained comparatively immune from the mindless violence during the Partition of the country. I have a vivid memory of an inscription, intact in 1951 but decimated soon after, of the name of Nawab Iftikhar Ali Khan on the front wall of the Gurudwara in Ahmedgarh for his donation of Rs. 500.00 – it must have been a princely sum in those days! I had instinctively developed a faith in the mutual accommodation among faiths long before I was destined to be an Indian diplomat in Iran, Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Maldives! This is a prologue to my tribute to late Syed Ali Jawad Zaidi (1916-2004), who embodied for me the highest virtues of all the faiths of mankind. -

Bhakti Movement

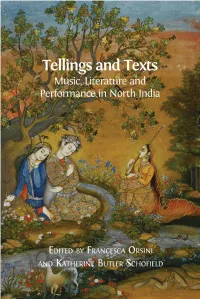

TELLINGS AND TEXTS Tellings and Texts Music, Literature and Performance in North India Edited by Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield http://www.openbookpublishers.com © Francesca Orsini and Katherine Butler Schofield. Copyright of individual chapters is maintained by the chapters’ authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work providing attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Orsini, Francesca and Butler Schofield, Katherine (eds.), Tellings and Texts: Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0062 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/4.0/ In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit: http://www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#copyright All external links were active on 22/09/2015 and archived via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine: https://archive.org/web/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at http:// www.openbookpublishers.com/isbn/9781783741021#resources ISBN Paperback: 978-1-78374-102-1 ISBN Hardback: 978-1-78374-103-8 ISBN Digital (PDF): 978-1-78374-104-5 ISBN Digital ebook (epub): 978-1-78374-105-2 ISBN Digital ebook (mobi): 9978-1-78374-106-9 DOI: 10.11647/OBP.0062 King’s College London has generously contributed to the publication of this volume. -

MUJEEBUDDIN SYED Nahi Tera Nasheman Khisr

MUJEEBUDDIN SYED Nahi tera nasheman khisr -sultani ke gumbad per Tu Shaheen hai! Basera kar pahadon ki chattanon mein "Not for you the nest on the dome of the Sultan's mansion You are the Eagle! You reside in the mountain's peaks." IQBAL W_/ALMAN RUSHDIE'S first novel, Grimus ( 1975) ,2 is marked by a characteristic heterogeneity that was to become the hallmark of later Rushdie novels. Strange and esoteric at times, Grimus has a referential sweep that assumes easy acquaintance with such diverse texts as Farid Ud 'Din Attar's The Conference of the Birds and Dante's Divina Commedia as well as an unaffected familiarity with mythologies as different as Hindu and Norse. Combining mythology and science fiction, mixing Oriental thought with Western modes, Grimus is in many ways an early manifesto of Rushdie's heterodoxical themes and innovative techniques. That Rushdie should have written this unconventional, cov• ertly subversive novel just three years after having completed his studies in Cambridge, where his area of study was, according to Khushwant Singh, "Mohammed, Islam and the Rise of the Caliphs" (1),3 is especially remarkable. The infinite number of allusions, insinuations, and puns in the novel not only reveals Rushdie's intimate knowledge of Islamic traditions and its trans• formed, hybrid, often-distorted picture that Western Orientalism spawned but also the variety of influences upon him stemming from Western literary tradition itself. At the heart of the hybrid nature of Grimus is an ingenuity that displaces what it has installed, so that the much-vaunted hybridity ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature, 25:4, October 1994 136 MUJEEBUDDIN SYED is itself stripped of all essentialized notions. -

' God Hath Treasuries Aneath the Throne, the Whereof

' God hath Treasuries aneath the Throne, the Keys whereof are the Tongues of the Poets.' - H a d i s i S h e r i f. HISTORY OF OTTOMAN POETRY BY E. J. W. GIBB, M. R. A.S. VOLUME I LONDON LUZAC & CO., GREAT RUSSELL STREET 1900 J V RA ^>^ (/ 'uL27 1S65 TV 0"^ TO^^t^^ 994016 PRINTED BY E. J. BRILL. LEYDEN. PREFACE. The History of Ottoman Literature has yet to be written. So far no serious work has been published, whether in Turkish or in any foreign language, that attempts to give a compre- hensive view of the whole field. Such books as have appeared up till now deal, like the present, with one side only, namely, Poetry. The reason why Ottoman prose has been thus neglected lies probably in the fact that until within the last half-century nearly all Turkish writing that was wholly or mainly literary or artistic in intention took the form of verse. Prose was as a rule reserved for practical and utilitarian purposes. Moreover, those few prose works that were artistic in aim, such as the Humayiin-Name and the later Khamsa-i Nergisi, were invariably elaborated upon the lines that at the time prevailed in poetry. Such works were of course not in metre; but this apart, their authors sought the same ends as did the poets, and sought to attain these by the same means. The merits and demerits of such writings there- fore are practically the same as those of the contemporary poetry. The History of Ottoman Poetry is thus nearly equi- valent to the History of Ottoman Literature. -

Non-Cooperation 1920-1922: Regional Aspects of the All India Mobilization

NON-COOPERATION 1920-1922: REGIONAL ASPECTS OF THE ALL INDIA MOBILIZATION Ph.D Thesis Submitted by: SAKINA ABBAS ZAIDI Under the Supervision of Dr. ROOHI ABIDA AHAMAD, Associate Professor Centre of Advance Study Department of History Aligarh Muslim University Aligarh(India) 2016 Acknowledgements I am immensely thankful to ‘Almighty Allah,’ and Ahlulbait (A.S), for the completion of my work in spirit and letter. It is a pleasant duty for me to acknowledge the kindness of all my teachers, friends, well-wishers and family with whose help and advice I was able to complete this work, as it is undeniable true that thesis writing involves other aiding you directly or indirectly. First and foremost, beholden to my supervisor, Dr. Roohi Abida Ahmed, for her encouragement, moral support, inspiring suggestions and excellent guidance. The help she extended to me was more than what I deserve. She always provided me with constructive and critical suggestions. I felt extraordinary fortunate with the attentiveness I was shown by her. I indeed consider myself immensely blessed in having someone so kind and supportive as my supervisor from whom I learnt a lot. A statement of thanks here falls very short for the gratitude I have for her mentorship. I gratefully acknowledge my debt to Professor Tariq Ahmed who helped a lot in picking up slips and lapses in the text and who has been a constant source of inspiration for me during the course of my study. I am thankful to Professor Ali Athar, Chairman and Coordinator, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, AMU, Aligarh for being always receptive and supportive. -

A Long History of Urdu Literary Culture, Part 1

ASPECTS OF EARLY URDU LITERARY CULTURE AND HISTORY By Shamsur Rahman Faruqi History, Faith, and Politics Using the term “early Urdu” is not without its risks. “Urdu” as a language name is of comparatively recent origin, and the question of what was or is “early Urdu” has long since passed from the realm of history, first into the colonialist constructions of the history of Urdu/Hindi, and then into the political and emotional space of Indian (=Hindu) identity in modern India. For the average Hindi-user today, it is a matter of faith to believe that the language he knows as “Hindi” is of ancient origin, and its literature originates with K. husrau (1253-1325), if not even earlier. Many such people also believe that the pristine “Hindī” or “Hindvī” became “Urdu” sometime in the eighteenth century, when the Muslims “decided” to veer away from “Hindī” as it existed at that time, and adopted a heavy, Persianised style of language which soon became a distinguishing characteristic of the Muslims of India. In recent times, this case was most elaborately presented by Amrit Rai (Amrit Rai 1984). Rai’s thesis, though full of inconsistencies or tendentious speculation rather than hard facts, and of fanciful interpretation of actual facts, was never refuted by Urdu scholars as it should have been. Quite a bit of the speculation that goes by the name of scholarly historiography of Hindi/Urdu language and literature today owes its existence to the fortuity of nomenclature. Early names for the language now called Urdu were, more or less in this order: 1) Hindvī; 2) Hindī; 3) Dihlavī; 4) Gujrī; 5) Dakanī; and 6) Rek.htah. -

Kocaer 3991.Pdf

Kocaer, Sibel (2015) The journey of an Ottoman arrior dervish : The Hı ırname (Book of Khidr) sources and reception. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/id/eprint/20392 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this PhD Thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This PhD Thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this PhD Thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the PhD Thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full PhD Thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD PhD Thesis, pagination. The Journey of an Ottoman Warrior Dervish: The Hızırname (Book of Khidr) Sources and Reception SIBEL KOCAER Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of the Languages and Cultures of the Near and Middle East SOAS, University of London Declaration for SOAS PhD thesis I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination.