Structure and Lattice Dynamics of Copper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington State Minerals Checklist

Division of Geology and Earth Resources MS 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington State 360-902-1450; 360-902-1785 fax E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/geology Minerals Checklist Note: Mineral names in parentheses are the preferred species names. Compiled by Raymond Lasmanis o Acanthite o Arsenopalladinite o Bustamite o Clinohumite o Enstatite o Harmotome o Actinolite o Arsenopyrite o Bytownite o Clinoptilolite o Epidesmine (Stilbite) o Hastingsite o Adularia o Arsenosulvanite (Plagioclase) o Clinozoisite o Epidote o Hausmannite (Orthoclase) o Arsenpolybasite o Cairngorm (Quartz) o Cobaltite o Epistilbite o Hedenbergite o Aegirine o Astrophyllite o Calamine o Cochromite o Epsomite o Hedleyite o Aenigmatite o Atacamite (Hemimorphite) o Coffinite o Erionite o Hematite o Aeschynite o Atokite o Calaverite o Columbite o Erythrite o Hemimorphite o Agardite-Y o Augite o Calciohilairite (Ferrocolumbite) o Euchroite o Hercynite o Agate (Quartz) o Aurostibite o Calcite, see also o Conichalcite o Euxenite o Hessite o Aguilarite o Austinite Manganocalcite o Connellite o Euxenite-Y o Heulandite o Aktashite o Onyx o Copiapite o o Autunite o Fairchildite Hexahydrite o Alabandite o Caledonite o Copper o o Awaruite o Famatinite Hibschite o Albite o Cancrinite o Copper-zinc o o Axinite group o Fayalite Hillebrandite o Algodonite o Carnelian (Quartz) o Coquandite o o Azurite o Feldspar group Hisingerite o Allanite o Cassiterite o Cordierite o o Barite o Ferberite Hongshiite o Allanite-Ce o Catapleiite o Corrensite o o Bastnäsite -

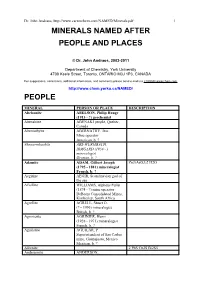

Minerals Named After Scientists

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 1 MINERALS NAMED AFTER PEOPLE AND PLACES © Dr. John Andraos, 2003-2011 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ PEOPLE MINERAL PERSON OR PLACE DESCRIPTION Abelsonite ABELSON, Philip Hauge (1913 - ?) geochemist Abenakiite ABENAKI people, Quebec, Canada Abernathyite ABERNATHY, Jess Mine operator American, b. ? Abswurmbachite ABS-WURMBACH, IRMGARD (1938 - ) mineralogist German, b. ? Adamite ADAM, Gilbert Joseph Zn3(AsO3)2 H2O (1795 - 1881) mineralogist French, b. ? Aegirine AEGIR, Scandinavian god of the sea Afwillite WILLIAMS, Alpheus Fuller (1874 - ?) mine operator DeBeers Consolidated Mines, Kimberley, South Africa Agrellite AGRELL, Stuart O. (? - 1996) mineralogist British, b. ? Agrinierite AGRINIER, Henri (1928 - 1971) mineralogist French, b. ? Aguilarite AGUILAR, P. Superintendent of San Carlos mine, Guanajuato, Mexico Mexican, b. ? Aikenite 2 PbS Cu2S Bi2S5 Andersonite ANDERSON, Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 2 Andradite ANDRADA e Silva, Jose B. Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 de (? - 1838) geologist Brazilian, b. ? Arfvedsonite ARFVEDSON, Johann August (1792 - 1841) Swedish, b. Skagerholms- Bruk, Skaraborgs-Län, Sweden Arrhenite ARRHENIUS, Svante Silico-tantalate of Y, Ce, Zr, (1859 - 1927) Al, Fe, Ca, Be Swedish, b. Wijk, near Uppsala, Sweden Avogardrite AVOGADRO, Lorenzo KBF4, CsBF4 Romano Amedeo Carlo (1776 - 1856) Italian, b. Turin, Italy Babingtonite (Ca, Fe, Mn)SiO3 Fe2(SiO3)3 Becquerelite BECQUEREL, Antoine 4 UO3 7 H2O Henri César (1852 - 1908) French b. Paris, France Berzelianite BERZELIUS, Jöns Jakob Cu2Se (1779 - 1848) Swedish, b. -

Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Page 1 Time's Arrow in the Trees of Life And

Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Time’s Arrow in the Trees of Life and Minerals Peter J. Heaney1,* 1Dept. of Geosciences, Penn State University, University Park, PA 16802 *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] Page 1 Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 1 ABSTRACT 2 Charles Darwin analogized the diversification of species to a Tree of Life. 3 This metaphor aligns precisely with the taxonomic system that Linnaeus developed 4 a century earlier to classify living species, because an underlying mechanism – 5 natural selection – has driven the evolution of new organisms over vast timescales. 6 On the other hand, the efforts of Linnaeus to extend his “universal” organizing 7 system to minerals has been regarded as an epistemological misfire that was 8 properly abandoned by the late nineteenth century. 9 The mineral taxonomies proposed in the wake of Linnaeus can be 10 distinguished by their focus on external character (Werner), crystallography (Haüy), 11 or chemistry (Berzelius). This article appraises the competition among these 12 systems and posits that the chemistry-based Berzelian taxonomy, as embedded 13 within the widely adopted system of James Dwight Dana, ultimately triumphed 14 because it reflects Earth’s episodic but persistent progression with respect to 15 chemical differentiation. In this context, Hazen et al.’s (2008) pioneering work in 16 mineral evolution reveals that even the temporal character of the phylogenetic Tree 17 of Life is rooted within a Danan framework for ordering minerals. 18 19 Page 1 Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 20 INTRODUCTION 21 In an essay dedicated to the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, Stephen Jay 22 Gould (2000) expresses his indignation at the sheer luckiness of Carolus Linnaeus 23 (1707-1778; Fig. -

Underactive Thyroid

Underactive Thyroid PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Thu, 21 Jun 2012 14:27:58 UTC Contents Articles Thyroid 1 Hypothyroidism 14 Nutrition 22 B vitamins 47 Vitamin E 53 Iodine 60 Selenium 75 Omega-6 fatty acid 90 Borage 94 Tyrosine 97 Phytotherapy 103 Fucus vesiculosus 107 Commiphora wightii 110 Nori 112 Desiccated thyroid extract 116 References Article Sources and Contributors 121 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 124 Article Licenses License 126 Thyroid 1 Thyroid thyroid Thyroid and parathyroid. Latin glandula thyroidea [1] Gray's subject #272 1269 System Endocrine system Precursor Thyroid diverticulum (an extension of endoderm into 2nd Branchial arch) [2] MeSH Thyroid+Gland [3] Dorlands/Elsevier Thyroid gland The thyroid gland or simply, the thyroid /ˈθaɪrɔɪd/, in vertebrate anatomy, is one of the largest endocrine glands. The thyroid gland is found in the neck, below the thyroid cartilage (which forms the laryngeal prominence, or "Adam's apple"). The isthmus (the bridge between the two lobes of the thyroid) is located inferior to the cricoid cartilage. The thyroid gland controls how quickly the body uses energy, makes proteins, and controls how sensitive the body is to other hormones. It participates in these processes by producing thyroid hormones, the principal ones being triiodothyronine (T ) and thyroxine which can sometimes be referred to as tetraiodothyronine (T ). These hormones 3 4 regulate the rate of metabolism and affect the growth and rate of function of many other systems in the body. T and 3 T are synthesized from both iodine and tyrosine. -

Chrisstanleyite Ag2pd3se4 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Chrisstanleyite Ag2Pd3Se4 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Monoclinic. Point Group: 2/m or 2. Anhedral crystals, to several hundred µm, aggregated in grains. Twinning: Fine polysynthetic and parquetlike, characteristic. Physical Properties: Tenacity: Slightly brittle. Hardness = ∼5 VHN = 371–421, 395 average (100 g load), D(meas.) = n.d. D(calc.) = 8.30 Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Silvery gray. Streak: Black. Luster: Metallic. Optical Class: Biaxial. Pleochroism: Slight; pale buff to slightly gray-green buff. Anisotropism: Moderate; rose-brown, gray-green, pale bluish gray, dark steel-blue. Bireflectance: Weak to moderate. R1–R2: (400) 35.6–43.3, (420) 36.8–44.2, (440) 37.8–45.3, (460) 39.1–46.7, (480) 40.0–47.5, (500) 41.1–48.0, (520) 42.1–48.5, (540) 42.9–48.7, (560) 43.5–49.1, (580) 44.1–49.3, (600) 44.4–49.5, (620) 44.6–49.6, (640) 44.5–49.3, (660) 44.4–49.2, (680) 44.2–49.1, (700) 44.0–49.0 Cell Data: Space Group: P 21/m or P 21. a = 6.350(6) b = 10.387(4) c = 5.683(3) β = 114.90(5)◦ Z=2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Hope’s Nose, England. 2.742 (100), 1.956 (100), 2.688 (80), 2.868 (50b), 2.367 (50), 1.829 (30), 2.521 (20) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Pd 37.64 35.48 37.52 Pt 0.70 Hg 0.36 Ag 25.09 24.07 25.36 Cu 0.18 2.05 Se 36.39 38.50 37.12 Total 99.30 101.16 100.00 (1) Hope’s Nose, England; by electron microprobe, average of 26 analyses; corresponding to (Ag2.01Cu0.02)Σ=2.03Pd3.02Se3.95. -

European Journal of Mineralogy

Title Grundmannite, CuBiSe<SUB>2</SUB>, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragón mine, Potosí, Bolivia Authors Förster, Hans-Jürgen; Bindi, L; Stanley, Christopher Date Submitted 2016-05-04 European Journal of Mineralogy Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragόn mine, Potosí, Bolivia --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: Article Type: Research paper Full Title: Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragόn mine, Potosí, Bolivia Short Title: Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, Corresponding Author: Hans-Jürgen Förster Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum GFZ Potsdam, GERMANY Corresponding Author E-Mail: [email protected] Order of Authors: Hans-Jürgen Förster Luca Bindi Chris J. Stanley Abstract: Grundmannite, ideally CuBiSe2, is a new mineral species from the El Dragόn mine, Department of Potosí, Bolivia. It is either filling small shrinkage cracks or interstices in brecciated kruta'ite−penroseite solid solutions or forms independent grains in the matrix. Grain size of the anhedral to subhedral crystals is usually in the range 50−150 µm, but may approach 250 µm. Grundmannite is usually intergrown with watkinsonite and clausthalite; other minerals occasionally being in intimate grain-boundary contact comprise quartz, dolomite, native gold, eskebornite, umangite, klockmannite, Co-rich penroseite, and three unnamed phases of the Cu−Bi−Hg−Pb−Se system, among which is an as-yet uncharacterizedspecies with the ideal composition Cu4Pb2HgBi4Se11. Eldragόnite and petrovicite rarely precipitated in the neighborhood of CuBiSe2. Grundmannite is non-fluorescent, black and opaque with a metallic luster and black streak. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,524,796 B2 Kim Et Al

US008524796B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8,524,796 B2 Kim et al. (45) Date of Patent: *Sep. 3, 2013 (54) ACTIVE POLYMER COMPOSITIONS WO 20060967.91 9, 2006 WO 2007024.125 3, 2007 (75) Inventors: Young-Sam Kim, Midland, MI (US); WO 20070785682007030791 3,7/2007 2007 Leonardo C. Lopez, Midland, MI (US); WO 2007099397 9, 2007 Scott T. Matteucci, Midland, MI (US); WO 2007121458 10/2007 Steven R. Lakso, Sanford, MI (US) WO 2008101051 8, 2008 WO 2008112833 9, 2008 (73) Assignee: Dow Global Technologies LLC WO 2008.150970 12/2008 WO 2009 134824 11, 2009 (*) Notice: Subject to any disclaimer, the term of this OTHER PUBLICATIONS patent is extended or adjusted under 35 U.S.C. 154(b) by 457 days. Ciferri, Alberto, “Supramolecular Polymers'. Second Edition, 2005, pp. 157-158, CRC Press. This patent is Subject to a terminal dis Corbin et al., “Chapter 6 Hydrogen-Bonded Supramolecular Poly claimer. mers: Linear and Network Polymers and Self-Assembling Discotic Polymers'. Supramolecular Polymers, 2nd edition, CRC Press, (21) Appl. No.: 12/539,793 2005, pp. 153-185. Duan et al., “Preparation of Antimicrobial Poly (e-caprolactone) (22) Filed: Aug. 12, 2009 Electrospun Nanofibers Containing Silver-Loaded Zirconium Phos phate Nanoparticles”, Journal of Applied Polymer Sciences, 2007. (65) Prior Publication Data vol. 106, pp. 1208-1214, Wiley Periodicals, Inc. US 201O/OO41292 A1 Feb. 18, 2010 Hagewood, "Potential of Polymeric Nanofibers for Nonwovens and Medical Applications'. Fiberjournal.com, Feb. 26, 2008, 4 Pages, Related U.S. Application Data J.Hagewood, LLC and Ben Shuler, Hills, Inc. -

Selenium Minerals and the Recovery of Selenium from Copper Refinery Anode Slimes by C

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2016/v116n6a16 Selenium minerals and the recovery of selenium from copper refinery anode slimes by C. Wang*, S. Li*, H. Wang*, and J. Fu* and genesis of native selenium from Yutangba, #65'272 Enshi City, Hubei Province, China in 2004, and pointed out, from the different forms of native Since it was first identified in 1817, selenium has received considerable Se, that selenium can be interest. Native selenium and a few selenium minerals were discovered several decades later. With the increasing number of selenium minerals, activated,transformed, remobilized, and the occurrence of selenium minerals became the focus of much research. A enriched at sites such as in the unsaturated great number of selenium deposits were reported all over the world, subsurface zone or in the saturated zone (Zhu although few independent selenium deposits were discovered. Selenium is et al., 2005). The transport and deposition of obtained mainly as a byproduct of other metals, and is produced primarily selenium in felsic volcanic-hosted massive from the anode mud of copper refineries. This paper presents a compre- sulphide deposits of the Yukon Territory, hensive review of selenium minerals, as well as the treatment of copper Canada was studied and reported by Layton- refinery anode slimes for the recovery of selenium. Our focus is on the Matthews et al. (2005). selenium minerals, including their discovery and occurrence, and the Selenium is a comparatively rare and distribution of selenium resources. In addition, the main methods of greatly dispersed element. The average recovering selenium from copper anode slimes are summarized. -

Eskebornite Cufese2 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal, Pseudocubic

Eskebornite CuFeSe2 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal, pseudocubic. Point Group: 42m. Crystals thick tabular, to 1 mm; massive, typically intergrown with other selenides. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {001}, perfect. Hardness = 3–3.5 VHN = 155–252, 204 average (15 g load). D(meas.) = 5.35 D(calc.) = 5.44 Distinctly magnetic. Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Brass-yellow, tarnishes dark brown to black; in reflected light, brown-yellow or cream-yellow, may show an orange tint. Luster: Metallic. Pleochroism: Weak, creamy yellow to yellowish brown. Anisotropism: Marked, yellowish to tan. R1–R2: (400) 22.0–24.5, (420) 24.8–27.9, (440) 26.5–30.1, (460) 27.8–31.8, (480) 28.7–33.1, (500) 29.5–34.2, (520) 30.4–35.0, (540) 31.1–35.6, (560) 31.6–36.0, (580) 32.0–36.2, (600) 32.6–36.4, (620) 33.0–36.6, (640) 33.3–37.0, (660) 33.7–37.5, (680) 33.8–38.1, (700) 34.0–38.7 Cell Data: Space Group: P 42c. a = 5.518(4) c = 11.048(6) Z = 4 X-ray Powder Pattern: Petrovice, Czech Republic. 3.186 (10), 1.951 (9), 1.664 (8), 5.52 (7), 1.127 (7), 1.380 (6), 2.470 (5) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Cu 23.62 22.97 22.91 Fe 19.75 20.70 20.14 Ag 0.05 Se 55.96 56.35 56.95 S 0.02 Total 99.32 100.09 100.00 (1) Martin Lake, Canada; by electron microprobe, average of several analyses; corresponding to Cu1.06Fe1.01Se2.00. -

Chemical Names and CAS Numbers Final

Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number C3H8O 1‐propanol C4H7BrO2 2‐bromobutyric acid 80‐58‐0 GeH3COOH 2‐germaacetic acid C4H10 2‐methylpropane 75‐28‐5 C3H8O 2‐propanol 67‐63‐0 C6H10O3 4‐acetylbutyric acid 448671 C4H7BrO2 4‐bromobutyric acid 2623‐87‐2 CH3CHO acetaldehyde CH3CONH2 acetamide C8H9NO2 acetaminophen 103‐90‐2 − C2H3O2 acetate ion − CH3COO acetate ion C2H4O2 acetic acid 64‐19‐7 CH3COOH acetic acid (CH3)2CO acetone CH3COCl acetyl chloride C2H2 acetylene 74‐86‐2 HCCH acetylene C9H8O4 acetylsalicylic acid 50‐78‐2 H2C(CH)CN acrylonitrile C3H7NO2 Ala C3H7NO2 alanine 56‐41‐7 NaAlSi3O3 albite AlSb aluminium antimonide 25152‐52‐7 AlAs aluminium arsenide 22831‐42‐1 AlBO2 aluminium borate 61279‐70‐7 AlBO aluminium boron oxide 12041‐48‐4 AlBr3 aluminium bromide 7727‐15‐3 AlBr3•6H2O aluminium bromide hexahydrate 2149397 AlCl4Cs aluminium caesium tetrachloride 17992‐03‐9 AlCl3 aluminium chloride (anhydrous) 7446‐70‐0 AlCl3•6H2O aluminium chloride hexahydrate 7784‐13‐6 AlClO aluminium chloride oxide 13596‐11‐7 AlB2 aluminium diboride 12041‐50‐8 AlF2 aluminium difluoride 13569‐23‐8 AlF2O aluminium difluoride oxide 38344‐66‐0 AlB12 aluminium dodecaboride 12041‐54‐2 Al2F6 aluminium fluoride 17949‐86‐9 AlF3 aluminium fluoride 7784‐18‐1 Al(CHO2)3 aluminium formate 7360‐53‐4 1 of 75 Chemical Abstract Chemical Formula Chemical Name Service (CAS) Number Al(OH)3 aluminium hydroxide 21645‐51‐2 Al2I6 aluminium iodide 18898‐35‐6 AlI3 aluminium iodide 7784‐23‐8 AlBr aluminium monobromide 22359‐97‐3 AlCl aluminium monochloride -

D. C. Hannrs, L. J. Cabnr Ano E. J. Munnev

AN OCCURRENCEOF A SULPHUR.BEARINGBERZELIANITE D. C. Hannrs,L. J. CaBnrano E. J. Munnev M,ines Branch, Departm,ent of Energy, M'ines anil, Resources,Ottawa, Canad,a Berzelianite is a selenide of copper with the formula Cuz_"Se.The binary Cu-Se system has been investigated by a number of workers, the most recent of which are Earley (1950), Borchert & Patzak (Lg5b), Heyding (1966) and Bernardini & Catani (1968). From the phase diagram, the cubic Cuz-rSe phase has a very narrow homogeneity range at room temperature, centered at approximately Cur.aSe,within the limits 0.15 ( r { 0.25. To date, no one has reported on the stability relations in the ternary system Cu-S-Se. During an investigation of the selenide minerals from Martin Lake, I ake Athabasca area, northern Saskatchewan,in which a new copper selenide mineral, athabascaite was found (Harris et al,. Ig6g), electron microprobe analysis showed that some of the berzelianite contained sulphur. The purpose of this paper is to report this first occurrenceof a naturally-occurring sulphur-bearing berzelianite. Gnnpnel DBscnrprrox The most common selenidesfrom the Martin Lake locality are uman- gite, berzelianite and clausthalite. Other minor selenides are klock- mannite, eucairite, tyrrellite, eskeborniteand athabascaite.The selenides occur in pitchblende ore and in hematite-stained carbonate vein material in the basalt of the Martin formation. The berzelianite that occursin the pitchblende ore is sulphur-free and it occurs as inclusions in, and replace- ments of, umangite. The sulphur-bearing berzelianite occurs as stringers and veinlets in the vein material. The mineral is associatedwith atha- bascaite, which in this environment is also sulphur-bearing, and with minor umangite. -

A Specific Gravity Index for Minerats

A SPECIFICGRAVITY INDEX FOR MINERATS c. A. MURSKyI ern R. M. THOMPSON, Un'fuersityof Bri.ti,sh Col,umb,in,Voncouver, Canad,a This work was undertaken in order to provide a practical, and as far as possible,a complete list of specific gravities of minerals. An accurate speciflc cravity determination can usually be made quickly and this information when combined with other physical properties commonly leads to rapid mineral identification. Early complete but now outdated specific gravity lists are those of Miers given in his mineralogy textbook (1902),and Spencer(M,i,n. Mag.,2!, pp. 382-865,I}ZZ). A more recent list by Hurlbut (Dana's Manuatr of M,i,neral,ogy,LgE2) is incomplete and others are limited to rock forming minerals,Trdger (Tabel,l,enntr-optischen Best'i,mmungd,er geste,i,nsb.ildend,en M,ineral,e, 1952) and Morey (Encycto- ped,iaof Cherni,cal,Technol,ogy, Vol. 12, 19b4). In his mineral identification tables, smith (rd,entifi,cati,onand. qual,itatioe cherai,cal,anal,ys'i,s of mineral,s,second edition, New york, 19bB) groups minerals on the basis of specificgravity but in each of the twelve groups the minerals are listed in order of decreasinghardness. The present work should not be regarded as an index of all known minerals as the specificgravities of many minerals are unknown or known only approximately and are omitted from the current list. The list, in order of increasing specific gravity, includes all minerals without regard to other physical properties or to chemical composition. The designation I or II after the name indicates that the mineral falls in the classesof minerals describedin Dana Systemof M'ineralogyEdition 7, volume I (Native elements, sulphides, oxides, etc.) or II (Halides, carbonates, etc.) (L944 and 1951).