Trace Element Geochemistry of Sulfides from the Ashadze-2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington State Minerals Checklist

Division of Geology and Earth Resources MS 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington State 360-902-1450; 360-902-1785 fax E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/geology Minerals Checklist Note: Mineral names in parentheses are the preferred species names. Compiled by Raymond Lasmanis o Acanthite o Arsenopalladinite o Bustamite o Clinohumite o Enstatite o Harmotome o Actinolite o Arsenopyrite o Bytownite o Clinoptilolite o Epidesmine (Stilbite) o Hastingsite o Adularia o Arsenosulvanite (Plagioclase) o Clinozoisite o Epidote o Hausmannite (Orthoclase) o Arsenpolybasite o Cairngorm (Quartz) o Cobaltite o Epistilbite o Hedenbergite o Aegirine o Astrophyllite o Calamine o Cochromite o Epsomite o Hedleyite o Aenigmatite o Atacamite (Hemimorphite) o Coffinite o Erionite o Hematite o Aeschynite o Atokite o Calaverite o Columbite o Erythrite o Hemimorphite o Agardite-Y o Augite o Calciohilairite (Ferrocolumbite) o Euchroite o Hercynite o Agate (Quartz) o Aurostibite o Calcite, see also o Conichalcite o Euxenite o Hessite o Aguilarite o Austinite Manganocalcite o Connellite o Euxenite-Y o Heulandite o Aktashite o Onyx o Copiapite o o Autunite o Fairchildite Hexahydrite o Alabandite o Caledonite o Copper o o Awaruite o Famatinite Hibschite o Albite o Cancrinite o Copper-zinc o o Axinite group o Fayalite Hillebrandite o Algodonite o Carnelian (Quartz) o Coquandite o o Azurite o Feldspar group Hisingerite o Allanite o Cassiterite o Cordierite o o Barite o Ferberite Hongshiite o Allanite-Ce o Catapleiite o Corrensite o o Bastnäsite -

Uraninite, Coffinite and Ningyoite from Vein-Type Uranium Deposits of the Bohemian Massif (Central European Variscan Belt)

minerals Article Uraninite, Coffinite and Ningyoite from Vein-Type Uranium Deposits of the Bohemian Massif (Central European Variscan Belt) Miloš René 1,*, ZdenˇekDolníˇcek 2, Jiˇrí Sejkora 2, Pavel Škácha 2,3 and Vladimír Šrein 4 1 Institute of Rock Structure and Mechanics, Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, 182 09 Prague, Czech Republic 2 Department of Mineralogy and Petrology, National Museum, 193 00 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] (Z.D.); [email protected] (J.S.); [email protected] (P.Š.) 3 Mining Museum Pˇríbram, 261 01 Pˇríbram, Czech Republic 4 Czech Geological Survey, 152 00 Prague, Czech Republic; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +420-266-009-228 Received: 26 November 2018; Accepted: 15 February 2019; Published: 19 February 2019 Abstract: Uraninite-coffinite vein-type mineralisation with significant predominance of uraninite over coffinite occurs in the Pˇríbram, Jáchymov and Horní Slavkov ore districts and the Pot ˚uˇcky, Zálesí and Pˇredboˇriceuranium deposits. These uranium deposits are hosted by faults that are mostly developed in low- to high-grade metamorphic rocks of the basement of the Bohemian Massif. Textural features and the chemical composition of uraninite, coffinite and ningyoite were studied using an electron microprobe. Collomorphic uraninite was the only primary uranium mineral in all deposits studied. The uraninites contained variable and elevated concentrations of PbO (1.5 wt %–5.4 wt %), CaO (0.7 wt %–8.3 wt %), and SiO2 (up to 10.0 wt %), whereas the contents of Th, Zr, REE and Y were usually below the detection limits of the electron microprobe. -

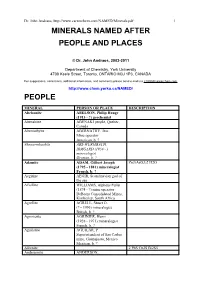

Minerals Named After Scientists

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 1 MINERALS NAMED AFTER PEOPLE AND PLACES © Dr. John Andraos, 2003-2011 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ PEOPLE MINERAL PERSON OR PLACE DESCRIPTION Abelsonite ABELSON, Philip Hauge (1913 - ?) geochemist Abenakiite ABENAKI people, Quebec, Canada Abernathyite ABERNATHY, Jess Mine operator American, b. ? Abswurmbachite ABS-WURMBACH, IRMGARD (1938 - ) mineralogist German, b. ? Adamite ADAM, Gilbert Joseph Zn3(AsO3)2 H2O (1795 - 1881) mineralogist French, b. ? Aegirine AEGIR, Scandinavian god of the sea Afwillite WILLIAMS, Alpheus Fuller (1874 - ?) mine operator DeBeers Consolidated Mines, Kimberley, South Africa Agrellite AGRELL, Stuart O. (? - 1996) mineralogist British, b. ? Agrinierite AGRINIER, Henri (1928 - 1971) mineralogist French, b. ? Aguilarite AGUILAR, P. Superintendent of San Carlos mine, Guanajuato, Mexico Mexican, b. ? Aikenite 2 PbS Cu2S Bi2S5 Andersonite ANDERSON, Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 2 Andradite ANDRADA e Silva, Jose B. Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 de (? - 1838) geologist Brazilian, b. ? Arfvedsonite ARFVEDSON, Johann August (1792 - 1841) Swedish, b. Skagerholms- Bruk, Skaraborgs-Län, Sweden Arrhenite ARRHENIUS, Svante Silico-tantalate of Y, Ce, Zr, (1859 - 1927) Al, Fe, Ca, Be Swedish, b. Wijk, near Uppsala, Sweden Avogardrite AVOGADRO, Lorenzo KBF4, CsBF4 Romano Amedeo Carlo (1776 - 1856) Italian, b. Turin, Italy Babingtonite (Ca, Fe, Mn)SiO3 Fe2(SiO3)3 Becquerelite BECQUEREL, Antoine 4 UO3 7 H2O Henri César (1852 - 1908) French b. Paris, France Berzelianite BERZELIUS, Jöns Jakob Cu2Se (1779 - 1848) Swedish, b. -

Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Page 1 Time's Arrow in the Trees of Life And

Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Time’s Arrow in the Trees of Life and Minerals Peter J. Heaney1,* 1Dept. of Geosciences, Penn State University, University Park, PA 16802 *To whom correspondence should be addressed: [email protected] Page 1 Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 1 ABSTRACT 2 Charles Darwin analogized the diversification of species to a Tree of Life. 3 This metaphor aligns precisely with the taxonomic system that Linnaeus developed 4 a century earlier to classify living species, because an underlying mechanism – 5 natural selection – has driven the evolution of new organisms over vast timescales. 6 On the other hand, the efforts of Linnaeus to extend his “universal” organizing 7 system to minerals has been regarded as an epistemological misfire that was 8 properly abandoned by the late nineteenth century. 9 The mineral taxonomies proposed in the wake of Linnaeus can be 10 distinguished by their focus on external character (Werner), crystallography (Haüy), 11 or chemistry (Berzelius). This article appraises the competition among these 12 systems and posits that the chemistry-based Berzelian taxonomy, as embedded 13 within the widely adopted system of James Dwight Dana, ultimately triumphed 14 because it reflects Earth’s episodic but persistent progression with respect to 15 chemical differentiation. In this context, Hazen et al.’s (2008) pioneering work in 16 mineral evolution reveals that even the temporal character of the phylogenetic Tree 17 of Life is rooted within a Danan framework for ordering minerals. 18 19 Page 1 Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 20 INTRODUCTION 21 In an essay dedicated to the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr, Stephen Jay 22 Gould (2000) expresses his indignation at the sheer luckiness of Carolus Linnaeus 23 (1707-1778; Fig. -

Eskebornite, Two Canadian Occurrences

ESKEBORNITE,TWO CANADIAN OCCURRENCES D.C. HARRIS* am E.A.T.BURKE *r, AssrRAcr The flnt Canadian occurrenceof eskebomitefrom Martin Lake and the Eagle Groug Lake Athabaskaare4 Northern Saskatchewanis reported.Electron microprobe agalysesshow that the formula is cuFese2.The r-ray powdet difiraction pattems are identical to that of eskebornitefrom Tilkerode, Germany,the type locality, Eskeborniteocrurs as island remnantsin, and replac'edby,'u,rnangite'which occurs in pitchblendeores in t}le basa.ltof the Martin formaiion and in granitizedmafic rocls of the Eaglegroup. The mineral can be readily synthesizedat 500"e from pure elements in evacuatedsilica glasstubes, Reflectance and micro-indentationhardness in."r*u**o are given. IlvrnonucttoN Eskebomite, a copper iron selenide, was first discovered and namd by P. Ramdohr in 1949 while studying the selenide minerals from dre Tilkerode area, Harz Mountain, Germany. The mineral has also been reported from Sierra de Cacheuta and Sierra de lJmango, Argentina (Tischendorf 1960). More recentlyo other occurrences of eskebornite have been described: by Kvadek et al. (1965) in the selenide paragenesis at the slavkovice locality in the Bohemian and Moravian Highlands, czecho- slovakia; and by Agrinier et aI. (1967) in veins of pitchblende at Cha- m6anq Puy-de-D6me, France. Earley (1950) and Tischendorf (195g, 1960) made.observations on eskebornite from the Tilkerode locality, but, even today, certain data are still lacking in the characterization of eskebomitg in particular its crystal- lographic symmetry. The purpose of this paper is to record the first occurrence of eskebomite in Canada and to present electron microprobe analyses, reflectance and micro-indentation hardness measurements. GrNsRAr. -

The Importance of Minerals in Coal As the Hosts of Chemical Elements: a Review

The importance of minerals in coal as the hosts of chemical elements: A review Robert B. Finkelmana,b, Shifeng Daia,c,*, David Frenchd a State Key Laboratory of Coal Resources and Safe Mining, China University of Mining and Technology, China b University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX 75080, USA c College of Geoscience and Survey Engineering, China University of Mining and Technology (Beijing), Beijing 100083, China d PANGEA Research Centre, School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia *, Corresponding author: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract Coal is a complex geologic material composed mainly of organic matter and mineral matter, the latter including minerals, poorly crystalline mineraloids, and elements associated with non- mineral inorganics. Among mineral matter, minerals play the most significant role in affecting the utilization of coal, although, in low rank coals, the non-mineral elements may also be significant. Minerals in coal are often regarded as a nuisance being responsible for most of the problems arising during coal utilization, but the minerals are also seen as a potentially valuable source of critical metals and may also, in some cases, have a beneficial effect in coal gasification and liquefaction. With a few exceptions, minerals are the major hosts of the vast majority of elements present in coal. In this review paper, we list more than 200 minerals that have been identified in coal and its low temperature ash, although the validity of some of these minerals has not been confirmed. Base on chemical compositions, minerals found in coal can be classified into silicate, sulfide and selenide, phosphate, carbonate, sulfate, oxide and hydroxide, and others. -

Chrisstanleyite Ag2pd3se4 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Chrisstanleyite Ag2Pd3Se4 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Monoclinic. Point Group: 2/m or 2. Anhedral crystals, to several hundred µm, aggregated in grains. Twinning: Fine polysynthetic and parquetlike, characteristic. Physical Properties: Tenacity: Slightly brittle. Hardness = ∼5 VHN = 371–421, 395 average (100 g load), D(meas.) = n.d. D(calc.) = 8.30 Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Silvery gray. Streak: Black. Luster: Metallic. Optical Class: Biaxial. Pleochroism: Slight; pale buff to slightly gray-green buff. Anisotropism: Moderate; rose-brown, gray-green, pale bluish gray, dark steel-blue. Bireflectance: Weak to moderate. R1–R2: (400) 35.6–43.3, (420) 36.8–44.2, (440) 37.8–45.3, (460) 39.1–46.7, (480) 40.0–47.5, (500) 41.1–48.0, (520) 42.1–48.5, (540) 42.9–48.7, (560) 43.5–49.1, (580) 44.1–49.3, (600) 44.4–49.5, (620) 44.6–49.6, (640) 44.5–49.3, (660) 44.4–49.2, (680) 44.2–49.1, (700) 44.0–49.0 Cell Data: Space Group: P 21/m or P 21. a = 6.350(6) b = 10.387(4) c = 5.683(3) β = 114.90(5)◦ Z=2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Hope’s Nose, England. 2.742 (100), 1.956 (100), 2.688 (80), 2.868 (50b), 2.367 (50), 1.829 (30), 2.521 (20) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Pd 37.64 35.48 37.52 Pt 0.70 Hg 0.36 Ag 25.09 24.07 25.36 Cu 0.18 2.05 Se 36.39 38.50 37.12 Total 99.30 101.16 100.00 (1) Hope’s Nose, England; by electron microprobe, average of 26 analyses; corresponding to (Ag2.01Cu0.02)Σ=2.03Pd3.02Se3.95. -

European Journal of Mineralogy

Title Grundmannite, CuBiSe<SUB>2</SUB>, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragón mine, Potosí, Bolivia Authors Förster, Hans-Jürgen; Bindi, L; Stanley, Christopher Date Submitted 2016-05-04 European Journal of Mineralogy Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragόn mine, Potosí, Bolivia --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: Article Type: Research paper Full Title: Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragόn mine, Potosí, Bolivia Short Title: Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, Corresponding Author: Hans-Jürgen Förster Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum GFZ Potsdam, GERMANY Corresponding Author E-Mail: [email protected] Order of Authors: Hans-Jürgen Förster Luca Bindi Chris J. Stanley Abstract: Grundmannite, ideally CuBiSe2, is a new mineral species from the El Dragόn mine, Department of Potosí, Bolivia. It is either filling small shrinkage cracks or interstices in brecciated kruta'ite−penroseite solid solutions or forms independent grains in the matrix. Grain size of the anhedral to subhedral crystals is usually in the range 50−150 µm, but may approach 250 µm. Grundmannite is usually intergrown with watkinsonite and clausthalite; other minerals occasionally being in intimate grain-boundary contact comprise quartz, dolomite, native gold, eskebornite, umangite, klockmannite, Co-rich penroseite, and three unnamed phases of the Cu−Bi−Hg−Pb−Se system, among which is an as-yet uncharacterizedspecies with the ideal composition Cu4Pb2HgBi4Se11. Eldragόnite and petrovicite rarely precipitated in the neighborhood of CuBiSe2. Grundmannite is non-fluorescent, black and opaque with a metallic luster and black streak. -

The Measurement of the Se/S Ratios in Sulphide Minerals and Their Application to Ore Deposit Studies

The measurement of the Se/S ratios in sulphide minerals and their application to ore deposit studies By Alexander John Fitzpatrick A thesis submitted to the Department of Geological Sciences and Geological Engineering in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada February, 2008 Copyright © Alexander John Fitzpatrick, 2008 Abstract New analytical techniques have been developed for the determination of selenium concentrations in sulphide minerals to assess the utility of the Se/S concentration ratios in tracing fluids associated with ore deposit formation. This has been accomplished via a new hydride generation (HG) sample introduction method for the determination of selenium contents in sulphide minerals, development of solid calibration standards by a sol-gel process, and the establishment of protocols for the measurement of selenium/sulphur ratios in sulphides using laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS). The low concentrations of selenium in sulphides require the use of hydride generation, which also requires the removal of metals to be effective. A process for the determination of selenium in sulphide minerals (~ 50 mg sample weight) wherein metals are removed by precipitation under alkaline conditions, followed by further removal by chelating resin, was developed. Determinations by HG-ICPMS on reference materials showed quantitative recoveries (100±5 %). Precision is 10 % relative standard deviation and the detection limit is 4 g g-1 in a sulphide mineral. A sol-gel method for the fabrication of multi-element calibration standards, suitable for laser ablation, was developed. The addition of selenium and sulphur to a normal sol-gel method does not introduce detectable heterogeneity. -

Selenium Minerals and the Recovery of Selenium from Copper Refinery Anode Slimes by C

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2016/v116n6a16 Selenium minerals and the recovery of selenium from copper refinery anode slimes by C. Wang*, S. Li*, H. Wang*, and J. Fu* and genesis of native selenium from Yutangba, #65'272 Enshi City, Hubei Province, China in 2004, and pointed out, from the different forms of native Since it was first identified in 1817, selenium has received considerable Se, that selenium can be interest. Native selenium and a few selenium minerals were discovered several decades later. With the increasing number of selenium minerals, activated,transformed, remobilized, and the occurrence of selenium minerals became the focus of much research. A enriched at sites such as in the unsaturated great number of selenium deposits were reported all over the world, subsurface zone or in the saturated zone (Zhu although few independent selenium deposits were discovered. Selenium is et al., 2005). The transport and deposition of obtained mainly as a byproduct of other metals, and is produced primarily selenium in felsic volcanic-hosted massive from the anode mud of copper refineries. This paper presents a compre- sulphide deposits of the Yukon Territory, hensive review of selenium minerals, as well as the treatment of copper Canada was studied and reported by Layton- refinery anode slimes for the recovery of selenium. Our focus is on the Matthews et al. (2005). selenium minerals, including their discovery and occurrence, and the Selenium is a comparatively rare and distribution of selenium resources. In addition, the main methods of greatly dispersed element. The average recovering selenium from copper anode slimes are summarized. -

Eskebornite Cufese2 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal, Pseudocubic

Eskebornite CuFeSe2 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal, pseudocubic. Point Group: 42m. Crystals thick tabular, to 1 mm; massive, typically intergrown with other selenides. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {001}, perfect. Hardness = 3–3.5 VHN = 155–252, 204 average (15 g load). D(meas.) = 5.35 D(calc.) = 5.44 Distinctly magnetic. Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Brass-yellow, tarnishes dark brown to black; in reflected light, brown-yellow or cream-yellow, may show an orange tint. Luster: Metallic. Pleochroism: Weak, creamy yellow to yellowish brown. Anisotropism: Marked, yellowish to tan. R1–R2: (400) 22.0–24.5, (420) 24.8–27.9, (440) 26.5–30.1, (460) 27.8–31.8, (480) 28.7–33.1, (500) 29.5–34.2, (520) 30.4–35.0, (540) 31.1–35.6, (560) 31.6–36.0, (580) 32.0–36.2, (600) 32.6–36.4, (620) 33.0–36.6, (640) 33.3–37.0, (660) 33.7–37.5, (680) 33.8–38.1, (700) 34.0–38.7 Cell Data: Space Group: P 42c. a = 5.518(4) c = 11.048(6) Z = 4 X-ray Powder Pattern: Petrovice, Czech Republic. 3.186 (10), 1.951 (9), 1.664 (8), 5.52 (7), 1.127 (7), 1.380 (6), 2.470 (5) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Cu 23.62 22.97 22.91 Fe 19.75 20.70 20.14 Ag 0.05 Se 55.96 56.35 56.95 S 0.02 Total 99.32 100.09 100.00 (1) Martin Lake, Canada; by electron microprobe, average of several analyses; corresponding to Cu1.06Fe1.01Se2.00. -

D. C. Hannrs, L. J. Cabnr Ano E. J. Munnev

AN OCCURRENCEOF A SULPHUR.BEARINGBERZELIANITE D. C. Hannrs,L. J. CaBnrano E. J. Munnev M,ines Branch, Departm,ent of Energy, M'ines anil, Resources,Ottawa, Canad,a Berzelianite is a selenide of copper with the formula Cuz_"Se.The binary Cu-Se system has been investigated by a number of workers, the most recent of which are Earley (1950), Borchert & Patzak (Lg5b), Heyding (1966) and Bernardini & Catani (1968). From the phase diagram, the cubic Cuz-rSe phase has a very narrow homogeneity range at room temperature, centered at approximately Cur.aSe,within the limits 0.15 ( r { 0.25. To date, no one has reported on the stability relations in the ternary system Cu-S-Se. During an investigation of the selenide minerals from Martin Lake, I ake Athabasca area, northern Saskatchewan,in which a new copper selenide mineral, athabascaite was found (Harris et al,. Ig6g), electron microprobe analysis showed that some of the berzelianite contained sulphur. The purpose of this paper is to report this first occurrenceof a naturally-occurring sulphur-bearing berzelianite. Gnnpnel DBscnrprrox The most common selenidesfrom the Martin Lake locality are uman- gite, berzelianite and clausthalite. Other minor selenides are klock- mannite, eucairite, tyrrellite, eskeborniteand athabascaite.The selenides occur in pitchblende ore and in hematite-stained carbonate vein material in the basalt of the Martin formation. The berzelianite that occursin the pitchblende ore is sulphur-free and it occurs as inclusions in, and replace- ments of, umangite. The sulphur-bearing berzelianite occurs as stringers and veinlets in the vein material. The mineral is associatedwith atha- bascaite, which in this environment is also sulphur-bearing, and with minor umangite.