Revision 2 of Ms. 5419 Page 1 Time's Arrow in the Trees of Life And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington State Minerals Checklist

Division of Geology and Earth Resources MS 47007; Olympia, WA 98504-7007 Washington State 360-902-1450; 360-902-1785 fax E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.dnr.wa.gov/geology Minerals Checklist Note: Mineral names in parentheses are the preferred species names. Compiled by Raymond Lasmanis o Acanthite o Arsenopalladinite o Bustamite o Clinohumite o Enstatite o Harmotome o Actinolite o Arsenopyrite o Bytownite o Clinoptilolite o Epidesmine (Stilbite) o Hastingsite o Adularia o Arsenosulvanite (Plagioclase) o Clinozoisite o Epidote o Hausmannite (Orthoclase) o Arsenpolybasite o Cairngorm (Quartz) o Cobaltite o Epistilbite o Hedenbergite o Aegirine o Astrophyllite o Calamine o Cochromite o Epsomite o Hedleyite o Aenigmatite o Atacamite (Hemimorphite) o Coffinite o Erionite o Hematite o Aeschynite o Atokite o Calaverite o Columbite o Erythrite o Hemimorphite o Agardite-Y o Augite o Calciohilairite (Ferrocolumbite) o Euchroite o Hercynite o Agate (Quartz) o Aurostibite o Calcite, see also o Conichalcite o Euxenite o Hessite o Aguilarite o Austinite Manganocalcite o Connellite o Euxenite-Y o Heulandite o Aktashite o Onyx o Copiapite o o Autunite o Fairchildite Hexahydrite o Alabandite o Caledonite o Copper o o Awaruite o Famatinite Hibschite o Albite o Cancrinite o Copper-zinc o o Axinite group o Fayalite Hillebrandite o Algodonite o Carnelian (Quartz) o Coquandite o o Azurite o Feldspar group Hisingerite o Allanite o Cassiterite o Cordierite o o Barite o Ferberite Hongshiite o Allanite-Ce o Catapleiite o Corrensite o o Bastnäsite -

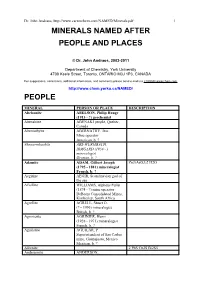

Minerals Named After Scientists

Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 1 MINERALS NAMED AFTER PEOPLE AND PLACES © Dr. John Andraos, 2003-2011 Department of Chemistry, York University 4700 Keele Street, Toronto, ONTARIO M3J 1P3, CANADA For suggestions, corrections, additional information, and comments please send e-mails to [email protected] http://www.chem.yorku.ca/NAMED/ PEOPLE MINERAL PERSON OR PLACE DESCRIPTION Abelsonite ABELSON, Philip Hauge (1913 - ?) geochemist Abenakiite ABENAKI people, Quebec, Canada Abernathyite ABERNATHY, Jess Mine operator American, b. ? Abswurmbachite ABS-WURMBACH, IRMGARD (1938 - ) mineralogist German, b. ? Adamite ADAM, Gilbert Joseph Zn3(AsO3)2 H2O (1795 - 1881) mineralogist French, b. ? Aegirine AEGIR, Scandinavian god of the sea Afwillite WILLIAMS, Alpheus Fuller (1874 - ?) mine operator DeBeers Consolidated Mines, Kimberley, South Africa Agrellite AGRELL, Stuart O. (? - 1996) mineralogist British, b. ? Agrinierite AGRINIER, Henri (1928 - 1971) mineralogist French, b. ? Aguilarite AGUILAR, P. Superintendent of San Carlos mine, Guanajuato, Mexico Mexican, b. ? Aikenite 2 PbS Cu2S Bi2S5 Andersonite ANDERSON, Dr. John Andraos, http://www.careerchem.com/NAMED/Minerals.pdf 2 Andradite ANDRADA e Silva, Jose B. Ca3Fe2(SiO4)3 de (? - 1838) geologist Brazilian, b. ? Arfvedsonite ARFVEDSON, Johann August (1792 - 1841) Swedish, b. Skagerholms- Bruk, Skaraborgs-Län, Sweden Arrhenite ARRHENIUS, Svante Silico-tantalate of Y, Ce, Zr, (1859 - 1927) Al, Fe, Ca, Be Swedish, b. Wijk, near Uppsala, Sweden Avogardrite AVOGADRO, Lorenzo KBF4, CsBF4 Romano Amedeo Carlo (1776 - 1856) Italian, b. Turin, Italy Babingtonite (Ca, Fe, Mn)SiO3 Fe2(SiO3)3 Becquerelite BECQUEREL, Antoine 4 UO3 7 H2O Henri César (1852 - 1908) French b. Paris, France Berzelianite BERZELIUS, Jöns Jakob Cu2Se (1779 - 1848) Swedish, b. -

Chrisstanleyite Ag2pd3se4 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1

Chrisstanleyite Ag2Pd3Se4 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Monoclinic. Point Group: 2/m or 2. Anhedral crystals, to several hundred µm, aggregated in grains. Twinning: Fine polysynthetic and parquetlike, characteristic. Physical Properties: Tenacity: Slightly brittle. Hardness = ∼5 VHN = 371–421, 395 average (100 g load), D(meas.) = n.d. D(calc.) = 8.30 Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Silvery gray. Streak: Black. Luster: Metallic. Optical Class: Biaxial. Pleochroism: Slight; pale buff to slightly gray-green buff. Anisotropism: Moderate; rose-brown, gray-green, pale bluish gray, dark steel-blue. Bireflectance: Weak to moderate. R1–R2: (400) 35.6–43.3, (420) 36.8–44.2, (440) 37.8–45.3, (460) 39.1–46.7, (480) 40.0–47.5, (500) 41.1–48.0, (520) 42.1–48.5, (540) 42.9–48.7, (560) 43.5–49.1, (580) 44.1–49.3, (600) 44.4–49.5, (620) 44.6–49.6, (640) 44.5–49.3, (660) 44.4–49.2, (680) 44.2–49.1, (700) 44.0–49.0 Cell Data: Space Group: P 21/m or P 21. a = 6.350(6) b = 10.387(4) c = 5.683(3) β = 114.90(5)◦ Z=2 X-ray Powder Pattern: Hope’s Nose, England. 2.742 (100), 1.956 (100), 2.688 (80), 2.868 (50b), 2.367 (50), 1.829 (30), 2.521 (20) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Pd 37.64 35.48 37.52 Pt 0.70 Hg 0.36 Ag 25.09 24.07 25.36 Cu 0.18 2.05 Se 36.39 38.50 37.12 Total 99.30 101.16 100.00 (1) Hope’s Nose, England; by electron microprobe, average of 26 analyses; corresponding to (Ag2.01Cu0.02)Σ=2.03Pd3.02Se3.95. -

European Journal of Mineralogy

Title Grundmannite, CuBiSe<SUB>2</SUB>, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragón mine, Potosí, Bolivia Authors Förster, Hans-Jürgen; Bindi, L; Stanley, Christopher Date Submitted 2016-05-04 European Journal of Mineralogy Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragόn mine, Potosí, Bolivia --Manuscript Draft-- Manuscript Number: Article Type: Research paper Full Title: Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, the Se-analogue of emplectite, a new mineral from the El Dragόn mine, Potosí, Bolivia Short Title: Composition and crystal structure of grundmannite, CuBiSe2, Corresponding Author: Hans-Jürgen Förster Deutsches GeoForschungsZentrum GFZ Potsdam, GERMANY Corresponding Author E-Mail: [email protected] Order of Authors: Hans-Jürgen Förster Luca Bindi Chris J. Stanley Abstract: Grundmannite, ideally CuBiSe2, is a new mineral species from the El Dragόn mine, Department of Potosí, Bolivia. It is either filling small shrinkage cracks or interstices in brecciated kruta'ite−penroseite solid solutions or forms independent grains in the matrix. Grain size of the anhedral to subhedral crystals is usually in the range 50−150 µm, but may approach 250 µm. Grundmannite is usually intergrown with watkinsonite and clausthalite; other minerals occasionally being in intimate grain-boundary contact comprise quartz, dolomite, native gold, eskebornite, umangite, klockmannite, Co-rich penroseite, and three unnamed phases of the Cu−Bi−Hg−Pb−Se system, among which is an as-yet uncharacterizedspecies with the ideal composition Cu4Pb2HgBi4Se11. Eldragόnite and petrovicite rarely precipitated in the neighborhood of CuBiSe2. Grundmannite is non-fluorescent, black and opaque with a metallic luster and black streak. -

Selenium Minerals and the Recovery of Selenium from Copper Refinery Anode Slimes by C

http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/2411-9717/2016/v116n6a16 Selenium minerals and the recovery of selenium from copper refinery anode slimes by C. Wang*, S. Li*, H. Wang*, and J. Fu* and genesis of native selenium from Yutangba, #65'272 Enshi City, Hubei Province, China in 2004, and pointed out, from the different forms of native Since it was first identified in 1817, selenium has received considerable Se, that selenium can be interest. Native selenium and a few selenium minerals were discovered several decades later. With the increasing number of selenium minerals, activated,transformed, remobilized, and the occurrence of selenium minerals became the focus of much research. A enriched at sites such as in the unsaturated great number of selenium deposits were reported all over the world, subsurface zone or in the saturated zone (Zhu although few independent selenium deposits were discovered. Selenium is et al., 2005). The transport and deposition of obtained mainly as a byproduct of other metals, and is produced primarily selenium in felsic volcanic-hosted massive from the anode mud of copper refineries. This paper presents a compre- sulphide deposits of the Yukon Territory, hensive review of selenium minerals, as well as the treatment of copper Canada was studied and reported by Layton- refinery anode slimes for the recovery of selenium. Our focus is on the Matthews et al. (2005). selenium minerals, including their discovery and occurrence, and the Selenium is a comparatively rare and distribution of selenium resources. In addition, the main methods of greatly dispersed element. The average recovering selenium from copper anode slimes are summarized. -

Eskebornite Cufese2 C 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, Version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal, Pseudocubic

Eskebornite CuFeSe2 c 2001-2005 Mineral Data Publishing, version 1 Crystal Data: Tetragonal, pseudocubic. Point Group: 42m. Crystals thick tabular, to 1 mm; massive, typically intergrown with other selenides. Physical Properties: Cleavage: {001}, perfect. Hardness = 3–3.5 VHN = 155–252, 204 average (15 g load). D(meas.) = 5.35 D(calc.) = 5.44 Distinctly magnetic. Optical Properties: Opaque. Color: Brass-yellow, tarnishes dark brown to black; in reflected light, brown-yellow or cream-yellow, may show an orange tint. Luster: Metallic. Pleochroism: Weak, creamy yellow to yellowish brown. Anisotropism: Marked, yellowish to tan. R1–R2: (400) 22.0–24.5, (420) 24.8–27.9, (440) 26.5–30.1, (460) 27.8–31.8, (480) 28.7–33.1, (500) 29.5–34.2, (520) 30.4–35.0, (540) 31.1–35.6, (560) 31.6–36.0, (580) 32.0–36.2, (600) 32.6–36.4, (620) 33.0–36.6, (640) 33.3–37.0, (660) 33.7–37.5, (680) 33.8–38.1, (700) 34.0–38.7 Cell Data: Space Group: P 42c. a = 5.518(4) c = 11.048(6) Z = 4 X-ray Powder Pattern: Petrovice, Czech Republic. 3.186 (10), 1.951 (9), 1.664 (8), 5.52 (7), 1.127 (7), 1.380 (6), 2.470 (5) Chemistry: (1) (2) (3) Cu 23.62 22.97 22.91 Fe 19.75 20.70 20.14 Ag 0.05 Se 55.96 56.35 56.95 S 0.02 Total 99.32 100.09 100.00 (1) Martin Lake, Canada; by electron microprobe, average of several analyses; corresponding to Cu1.06Fe1.01Se2.00. -

D. C. Hannrs, L. J. Cabnr Ano E. J. Munnev

AN OCCURRENCEOF A SULPHUR.BEARINGBERZELIANITE D. C. Hannrs,L. J. CaBnrano E. J. Munnev M,ines Branch, Departm,ent of Energy, M'ines anil, Resources,Ottawa, Canad,a Berzelianite is a selenide of copper with the formula Cuz_"Se.The binary Cu-Se system has been investigated by a number of workers, the most recent of which are Earley (1950), Borchert & Patzak (Lg5b), Heyding (1966) and Bernardini & Catani (1968). From the phase diagram, the cubic Cuz-rSe phase has a very narrow homogeneity range at room temperature, centered at approximately Cur.aSe,within the limits 0.15 ( r { 0.25. To date, no one has reported on the stability relations in the ternary system Cu-S-Se. During an investigation of the selenide minerals from Martin Lake, I ake Athabasca area, northern Saskatchewan,in which a new copper selenide mineral, athabascaite was found (Harris et al,. Ig6g), electron microprobe analysis showed that some of the berzelianite contained sulphur. The purpose of this paper is to report this first occurrenceof a naturally-occurring sulphur-bearing berzelianite. Gnnpnel DBscnrprrox The most common selenidesfrom the Martin Lake locality are uman- gite, berzelianite and clausthalite. Other minor selenides are klock- mannite, eucairite, tyrrellite, eskeborniteand athabascaite.The selenides occur in pitchblende ore and in hematite-stained carbonate vein material in the basalt of the Martin formation. The berzelianite that occursin the pitchblende ore is sulphur-free and it occurs as inclusions in, and replace- ments of, umangite. The sulphur-bearing berzelianite occurs as stringers and veinlets in the vein material. The mineral is associatedwith atha- bascaite, which in this environment is also sulphur-bearing, and with minor umangite. -

A Specific Gravity Index for Minerats

A SPECIFICGRAVITY INDEX FOR MINERATS c. A. MURSKyI ern R. M. THOMPSON, Un'fuersityof Bri.ti,sh Col,umb,in,Voncouver, Canad,a This work was undertaken in order to provide a practical, and as far as possible,a complete list of specific gravities of minerals. An accurate speciflc cravity determination can usually be made quickly and this information when combined with other physical properties commonly leads to rapid mineral identification. Early complete but now outdated specific gravity lists are those of Miers given in his mineralogy textbook (1902),and Spencer(M,i,n. Mag.,2!, pp. 382-865,I}ZZ). A more recent list by Hurlbut (Dana's Manuatr of M,i,neral,ogy,LgE2) is incomplete and others are limited to rock forming minerals,Trdger (Tabel,l,enntr-optischen Best'i,mmungd,er geste,i,nsb.ildend,en M,ineral,e, 1952) and Morey (Encycto- ped,iaof Cherni,cal,Technol,ogy, Vol. 12, 19b4). In his mineral identification tables, smith (rd,entifi,cati,onand. qual,itatioe cherai,cal,anal,ys'i,s of mineral,s,second edition, New york, 19bB) groups minerals on the basis of specificgravity but in each of the twelve groups the minerals are listed in order of decreasinghardness. The present work should not be regarded as an index of all known minerals as the specificgravities of many minerals are unknown or known only approximately and are omitted from the current list. The list, in order of increasing specific gravity, includes all minerals without regard to other physical properties or to chemical composition. The designation I or II after the name indicates that the mineral falls in the classesof minerals describedin Dana Systemof M'ineralogyEdition 7, volume I (Native elements, sulphides, oxides, etc.) or II (Halides, carbonates, etc.) (L944 and 1951). -

Selenium Recovery in Precious Metal Technology

Selenium Recovery in Precious Metal Technology Fabian Kling Willig Degree Project in Engineering Chemistry, 30 hp Report passed: February 2014 Supervisors: Tomas Hedlund, Umeå University Mikhail Maliarik, Outotec (Sweden) AB Abstract Selenium is mostly extracted from copper anode slimes because the selenium-rich ores are too rare to be mined with profit. When copper anode slimes are processed in a precious metal plant the first step is to remove copper by pressure leach in an autoclave. The anode slime is then dried and fed into a Kaldo furnace. The Kaldo is heated and reduction and smelting begins. During reduction, slag builders are added to form a slag with impurities and fluxes with coke breeze are added to reduce precious metal. In the oxidation step, selenium dioxide, sulphur dioxide and some tellurium dioxide are removed along with the process gas. The dioxides and the process gas are captured in a circulating venturi solution in the gas cleaning system. The dioxides lowers the pH of the venturi solution. Sodium hydroxide is added to the solution to keep pH above 4 in order to prevent selenium from precipitating in the circulation tank. After a Kaldo cycle, the venturi solution is transferred to a precipitation tank where sulphur dioxide is added in order to precipitate selenium. The precipitated selenium is finally collected in a filter press and sold as crude (99.5%) selenium. During commissioning of a precious metal plant and during processing of 2 batches anode slime, data such as pH and electrochemical potential was collected from the venturi solution and later shown in a Pourbaix diagram. -

Trace Element Geochemistry of Sulfides from the Ashadze-2

minerals Article Trace Element Geochemistry of Sulfides from the ◦ 0 Ashadze-2 Hydrothermal Field (12 58 N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge): Influence of Host Rocks, Formation Conditions or Seawater? Irina Melekestseva 1,*, Valery Maslennikov 1, Gennady Tret’yakov 1, Svetlana Maslennikova 1, Leonid Danyushevsky 2 , Vasily Kotlyarov 1, Ross Large 2, Victor Beltenev 3 and Pavel Khvorov 1 1 Institute of Mineralogy, South Urals Federal Research Center of Mineralogy and Geoecology UB RAS, Chelyabinsk District, 456317 Miass, Russia; [email protected] (V.M.); [email protected] (G.T.); [email protected] (S.M.); [email protected] (V.K.); [email protected] (P.K.) 2 CODES ARC Centre of Excellence in Ore Deposits, University of Tasmania, 7001 Hobart, Australia; [email protected] (L.D.); [email protected] (R.L.) 3 VNIIOkeangeologiya, 190121 St. Petersburg, Russia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-9507447301 Received: 29 June 2020; Accepted: 17 August 2020; Published: 22 August 2020 Abstract: The trace element (TS) composition of isocubanite, chalcopyrite, pyrite, bornite, and covellite from oxidized Cu-rich massive sulfides of the Ashadze-2 hydrothermal field (12◦580 N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge) is studied using LA-ICP-MS. The understanding of TE behavior, which depends on the formation conditions and the mode of TE occurrence, in sulfides is important, since they are potential sources for byproduct TEs. Isocubanite has the highest Co contents). Chalcopyrite concentrates most Au. Bornite has the highest amounts of Se, Sn, and Te. Crystalline pyrite is a main carrier of Mn. Covellite after isocubanite is a host to the highest Sr, Ag, and Bi contents. -

The New IMA List of Minerals – a Work in Progress – Updated: March 2020

The New IMA List of Minerals – A Work in Progress – Updated: March 2020 In the following pages of this document a comprehensive list of all valid mineral species is presented. The list is distributed (for terms and conditions see below) via the web site of the Commission on New Minerals, Nomenclature and Classification of the International Mineralogical Association, which is the organization in charge for approval of new minerals, and more in general for all issues related to the status of mineral species. The list, which will be updated on a regular basis, is intended as the primary and official source on minerals. Explanation of column headings: Name : it is the presently accepted mineral name (and in the table, minerals are sorted by name). CNMMN/CNMNC approved formula : it is the chemical formula of the mineral. IMA status : A = approved (it applies to minerals approved after the establishment of the IMA in 1958); G = grandfathered (it applies to minerals discovered before the birth of IMA, and generally considered as valid species); Rd = redefined (it applies to existing minerals which were redefined during the IMA era); Rn = renamed (it applies to existing minerals which were renamed during the IMA era); Q = questionable (it applies to poorly characterized minerals, whose validity could be doubtful). IMA No. / Year : for approved minerals the IMA No. is given: it has the form XXXX-YYY, where XXXX is the year and YYY a sequential number; for grandfathered minerals the year of the original description is given. In some cases, typically for Rd and Rn minerals, the year may be followed by s.p. -

The Thermodynamics of Selenium Minerals in Near-Surface Environments

minerals Review The Thermodynamics of Selenium Minerals in Near-Surface Environments Vladimir G. Krivovichev 1,*, Marina V. Charykova 2 ID and Andrey V. Vishnevsky 2 1 Department of Mineralogy, Institute of Earth Sciences, St. Petersburg State University, 7/9 University Embankment, Saint Petersburg 199034, Russia 2 Department of Geochemistry, Institute of Earth Sciences, St. Petersburg State University, 7/9 University Embankment, Saint Petersburg 199034, Russia; [email protected] (M.V.C.); [email protected] (A.V.V.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +7-812-328-9481 Received: 18 August 2017; Accepted: 4 October 2017; Published: 6 October 2017 Abstract: Selenium compounds are relatively rare as minerals; there are presently only 118 known mineral species. This work is intended to codify and systematize the data of mineral systems and the thermodynamics of selenium minerals, which are unstable (selenides) or formed in near-surface environments (selenites), where the behavior of selenium is controlled by variations of the redox potential and the acidity of solutions at low temperatures and pressures. These parameters determine the migration of selenium and its precipitation as various solid phases. All selenium minerals are divided into four groups—native selenium, oxide, selenides, and oxysalts—anhydrous selenites (I) and hydrous selenites and selenates (II). Within each of the groups, minerals are codified according to the minimum number of independent elements necessary to define the composition of the mineral system. Eh–pH diagrams were calculated and plotted using the Geochemist’s Workbench (GMB 9.0) software package. The Eh–pH diagrams of the Me–Se–H2O systems (where Me = Co, Ni, Fe, Cu, Pb, Zn, Cd, Hg, Ag, Bi, As, Sb, Al and Ca) were plotted for the average contents of these elements in acidic waters in the oxidation zones of sulfide deposits.