Note: the Hebrew Scriptures at the Time of Christ Were Combined and Arranged Differently Than Our Old Testament Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reconstruction Or Reformation the Conciliar Papacy and Jan Hus of Bohemia

Garcia 1 RECONSTRUCTION OR REFORMATION THE CONCILIAR PAPACY AND JAN HUS OF BOHEMIA Franky Garcia HY 490 Dr. Andy Dunar 15 March 2012 Garcia 2 The declining institution of the Church quashed the Hussite Heresy through a radical self-reconstruction led by the conciliar reformers. The Roman Church of the late Middle Ages was in a state of decline after years of dealing with heresy. While the Papacy had grown in power through the Middle Ages, after it fought the crusades it lost its authority over the temporal leaders in Europe. Once there was no papal banner for troops to march behind to faraway lands, European rulers began fighting among themselves. This led to the Great Schism of 1378, in which different rulers in Europe elected different popes. Before the schism ended in 1417, there were three popes holding support from various European monarchs. Thus, when a new reform movement led by Jan Hus of Bohemia arose at the beginning of the fifteenth century, the declining Church was at odds over how to deal with it. The Church had been able to deal ecumenically (or in a religiously unified way) with reforms in the past, but its weakened state after the crusades made ecumenism too great a risk. Instead, the Church took a repressive approach to the situation. Bohemia was a land stained with a history of heresy, and to let Hus's reform go unchecked might allow for a heretical movement on a scale that surpassed even the Cathars of southern France. Therefore the Church, under guidance of Pope John XXIII and Holy Roman Emperor Sigismund of Luxemburg, convened in the Council of Constance in 1414. -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

The Anti-Catholic Bible – Part I the Anti‐Catholic Bible

The Anti-Catholic Bible – Part I The Anti‐Catholic Bible Loraine Boettner was a member of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church in the first part of the 20th century – and an anti‐Catholic of the highest order. In 1962, he wrote a book called “Roman Catholicism”, which quickly became THE authoritative source for Protestant clergy regarding all things Catholic. The problem is that MOST of it is simply false. The following list of “Catholic Inventions” is taken right out of Boettner’s deeply flawed and defamatory book. He plays fast and loose with the facts and dates in his vilifying diatribe against the Church. It’s disturbing that in this day of so much available information, many non‐ Catholic groups still use this bogus list to find fault with the Catholic Church – never investigating the fact that most of its claims are patently false, petty and embarrassingly ignorant. This list or variations of it on can be found on many anti‐Catholic websites and literature. The Anti‐Catholic Bible (cont’d) Boettner wanted to cast a negative light on the disciplines introduced by the Catholic Church and doctrines declared. He wanted to show that they were nothing more than man‐made “inventions” because they were not explicitly taught in the Bible. As you will see, he was dead wrong. The doctrinal and dogmatic decrees made by the Church are Scripturally‐based while other matters of discipline were declared to accommodate the needs of the growing worldwide Church. Aside from Boettner’s attacks being false, it is interesting to note that Protestants have also added some of their own traditions such as altar calls, individual interpretation of Scripture, the withholding of baptism from infants and Sola Scriptura that have no basis in Scripture. -

The Canon of Scripture October 7, 2019

How to Study the Bible – The Canon of Scripture October 7, 2019 Recommended Resources “Scripture Alone” – James White “The Canon of Scripture” – Samuel Waldron Introduction – What is the Purpose of God’s Word? To accomplish His purpose Isa 55:9-11 For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts. (10) "For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven and do not return there but water the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater, (11) so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and shall succeed in the thing for which I sent it. To equip believers 2Ti 3:16-17 All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, (17) that the man of God may be competent, equipped for every good work. To defend the church Acts 20:26-30 Therefore I testify to you this day that I am innocent of the blood of all of you, (27) for I did not shrink from declaring to you the whole counsel of God . (28) Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God, which he obtained with his own blood. (29) I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock ; (30) and from among your own selves will arise men speaking twisted things, to draw away the disciples after them. -

A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature Harry E

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Graduate Theses Archives and Special Collections 1967 A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature Harry E. Woodall Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/grad_theses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Woodall, Harry E., "A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature" (1967). Graduate Theses. 31. http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/grad_theses/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE SIN AND DFATH OF MOSES IN BIBLICAL LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Ouachita Baptist University Arkadelphia, Arkansas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Harry E. Woodall August, 1967 A STUDY OF THE SIN AND DFATH OF MOSES IN BIBLICAL LITERATURE APPROVED: I L.t;z -~ >tuJ.!uJr) Major rofessor iv CHAPTER PAGE The Devil's Claim of Moses in Jude ••••• 42 A Critical Review of Jude • • • • • • • • 42 The Purpose of Jude • • • • • • • • • • • 47 The Interpretation of Jude 9 • • • • • • • 47 The Appearance of Moses to Christ in Mark • 49 Witness of the Other Passages • • • • • • 50 General Background of the Transfiguration 51 A Critical Analysis of the Transfiguration • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 Interpretation of the Transfiguration • • 58 Moses and Elijah in the Transfiguration • 60 A Belief in the Return of Moses • • • • • 64 Moses as a Heavenly Being • • • • • • • • 64 A New Testament Theology of Moses •••• 65 Moses in Extra-Biblical Literature •••• 67 IV. -

The Latin Fathers the 3Nd

GOOD SHEPHERD LUTHERAN CHURCH Gaithersburg, Maryland The History of the Early Christian Church Unit Two – The Early Church Fathers “Who Were They?” “Why Do We Remember Them?” The Latin Fathers The 3nd. of Three Sessions in Unit Two The 7th Sunday of Easter - The Sunday after the Ascension – May 14, 2020 (Originally Scheduled / Prepared for the 4th Sunday of Lent, 2020) I. Now Just Where Were We? It has been a long time since we were considering the Church Fathers in Unit 2. This is a “pick up session,” now that we have completed the 14 other sessions of this series on The History of the Early Christian Church. Some may remember that we were giving our attention to the early Church Fathers when the interruption of the Covid19 virus descended upon us, and we found ourselves under stay at home policies. Thanks to our pastor’s leadership ond our well equipped communications equipment and the skill of Pilip Muschke, we were able to be “on line` almost St. Jerome - Translator of Latin Vulgate instanetly. We missed only one session between our live class 4-5th Century and our first on line class. Today, we pick up the session we missed. We had covered two sessions of the three session Unit 2. The first of these sessions was on The Apostolic Fathers. These were those who had either known our Lord or known those who did. Among those would have been the former disciples of Jesus or the early first generation apostles. These were the primary sources to whom the ministry of our Lord was “handed off.” Saint Paul was among them. -

The Petrine Ministry at the Time of the First Four Ecumenical Councils

The Petrine ministry at the time of the first four ecumenical councils: relations between the Bishop of Rome and the Eastern Bishops as revealed in the canons, process, and reception of the councils Author: Pierluigi De Lucia Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/1852 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2010 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. BOSTON COLLEGE SCHOOL OF THEOLOGY AND MINISTRY WESTON JESUIT DEPARTEMENT The Petrine ministry at the Time of the First Four Ecumenical Councils Relations between the Bishop of Rome and the Eastern Bishops as revealed in the canons, process, and reception of the councils A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the S.T.L. Degree Of the School of Theology and Ministry By: Pierluigi De Lucia, S.J. Directed by: Francine Cardman Second Reader: Francis A. Sullivan, S.J. May 2010 © Copyright by Pierluigi DE LUCIA, S.J. 2010 Abstract The Petrine ministry of the bishops of Rome and relations with the eastern bishops at the time of the first four ecumenical councils are the focus of this thesis. It places the Church in the complex historical context marked by the public recognition of Christianity under Constantine (312) and the great novelty of the close interactions of the emperors with the bishops of the major sees in the period, Rome, Alexandria, Antioch and Constantinople. The study examines the structures of the church (local and regional synods and ecumenical councils) and the roles of bishops and emperors in the ecumenical councils of Nicaea (325), Constantinople I (381), Ephesus (431), and Chalcedon (451), including the “robber” council of 449. -

Areas of Doctrinal Differences

PART 2 AREAS OF DOCTRINAL DIFFERENCES In the first part of this volume we have stressed what evangelicals have in common with Roman Catholics. In short, this includes the great fundamentals of the Christian faith, including a belief in the Trinity, the virgin birth, the deity of Christ, the creation and subsequent fall of humanity, Christ’s unique atonement for our sins, the physical resurrection of Christ, the necessity of God’s grace for salvation, the existence of heaven and hell, the second coming of Christ, and the verbal inspiration and infallibility of Scripture. In spite of all these similarities in belief, however, there are some significant differences between Catholics and evangelicals on some important doctrines. Catholics affirm and evangelicals reject the immaculate conception of Mary, her bodily assumption, her role as corredemptrix, the veneration of Mary and other saints, prayers to Mary and the saints, the infallibility of the pope, the existence of purgatory, the inspiration and canonicity of the Apocrypha, the doctrine of transubstantiation, the worship of the transformed Host, the special sacerdotal powers of the Roman Catholic priesthood, and the necessity of works to obtain eternal life. Since all of these have been proclaimed as infallible dogma by the Roman Catholic Church, and since many are contrary to central teachings of evangelicalism, there appears to be no hope of ecumenical or ecclesiastical unity. Here we must recognize our differences and agree to disagree agreeably, knowing that there are many doctrines we hold in common (see Part One) and many things we can do together morally, socially, and educationally (see Part Three). -

Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies

0 Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies Bibliography largely taken from Dr. James R. Davila's annotated bibliographies: http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/~www_sd/otpseud.html. I have changed formatting, added the section on 'Online works,' have added a sizable amount to the secondary literature references in most of the categories, and added the Table of Contents. - Lee Table of Contents Online Works……………………………………………………………………………………………...02 General Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...…03 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………....03 Translations of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in Collections…………………………………….…03 Guide Series…………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 On the Literature of the 2nd Temple Period…………………………………………………………..........04 Literary Approaches and Ancient Exegesis…………………………………………………………..…...05 On Greek Translations of Semitic Originals……………………………………………………………....05 On Judaism and Hellenism in the Second Temple Period…………………………………………..…….06 The Book of 1 Enoch and Related Material…………………………………………………………….....07 The Book of Giants…………………………………………………………………………………..……09 The Book of the Watchers…………………………………………………………………………......….11 The Animal Apocalypse…………………………………………………………………………...………13 The Epistle of Enoch (Including the Apocalypse of Weeks)………………………………………..…….14 2 Enoch…………………………………………………………………………………………..………..15 5-6 Ezra (= 2 Esdras 1-2, 15-16, respectively)……………………………………………………..……..17 The Treatise of Shem………………………………………………………………………………..…….18 The Similitudes of Enoch (1 Enoch 37-71)…………………………………………………………..…...18 The -

Syllabus and Text

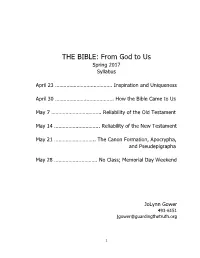

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

St. Ambrose and the Architecture of the Churches of Northern Italy : Ecclesiastical Architecture As a Function of Liturgy

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2008 St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy. Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider 1948- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Schneider, Sylvia Crenshaw 1948-, "St. Ambrose and the architecture of the churches of northern Italy : ecclesiastical architecture as a function of liturgy." (2008). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1275. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1275 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B.A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Art History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2008 Copyright 2008 by Sylvia A. Schneider All rights reserved ST. AMBROSE AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF THE CHURCHES OF NORTHERN ITALY: ECCLESIASTICAL ARCHITECTURE AS A FUNCTION OF LITURGY By Sylvia Crenshaw Schneider B. A., University of Missouri, 1970 A Thesis Approved on November 22, 2008 By the following Thesis Committee: ____________________________________________ Dr. -

Manuel Reyes Short History of the Bible † the Bible Is the Collection Of

Manuel Reyes Yesterday at 1:16am Short History of the Bible † The Bible is the collection of books that the Catholic Church decided could be read at Mass. It is a collection of books written by different authors with different writing styles over thousands of years for different audiences. It is not a manual on how to run a religion or build a church. Those things already existed before the Bible was assembled. The Didache is the earliest manual on how to run a Church. In modern times the Catholic Church is governed by Canon Law and the Catechism which is based on Scripture. At the time of Jesus, the Sadducees, that taught and worshiped at the Temple in Jerusalem, considered only the 5 books of Moses to be the word of God. The Pharisees and Rabbis that taught and worshiped in the Synagogues, considered the 5 books of Moses, the writings of the Prophets, the Psalms, and some of the historical writings as Scripture grouped in sets of 22 or 24 books. Jews living outside of Jerusalem used a Greek Translation of the Old Testament called the Septuagint. This translation has the 46 books of the Catholic Canon of the Old Testament in it, and various others that did not make it into the Catholic Old Testament. The 7 books that are in the Catholic Old Testament but not the Protestant Old Testament are 1st and 2nd Maccabees, Wisdom, Baruch, Sirach, Tobit, and Judith. The Early Christians considered the Greek Septuagint version of the Hebrew writings as Scripture. The New Testament usually quotes from the Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament.