A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature Harry E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biblical Interpretation

Biblical Interpretation Encounter: Experiencing God in Everyday Ascension Press BI 200.49 Interactive 2013 DVD Eight 30 min sesssions Part of a Series Encounter: Experiencing God in the Everyday is more than a Bible study program. It is a life- changing experience that speaks directly to the hearts and minds of middle school aged kids. Designed specifically for 6th to 8th grades, Encounter uses the color-coded Bible Timeline learning system to reveal the story of our faith and God’s plan for our lives. Galatians: Set Free to Live Ascension Press BI 200.47 Interactive 2013 DVD Eight 50 min sessions Part of a Series Paul’s letter to the Galatians speaks directly to the heart of Christians and addresses the most important question we can ask: “What must we do to be saved?” This fascinating letter reveals the merciful love that God the Father has for us, his children. It speaks of the extraordinary gift of salvation that Jesus has won for us, and it explains how we can unite ourselves to Christ’s redeeming sacrifice through faith and love. Galatians is a study that will reignite your love for God as you learn of the astonishing love God has for you. Tuesday, December 17, 2013 Biblical Interpretation Page 1 of 17 The Christ: A Faithful Picture of Jesus from the Gospels Saint Benedict Press BI 200.34 Instructional 2011 DVD Eight 30 min. sessions Part of a Series The best place to find out who Jesus is in the Bible, specifically in the Gospels. All four evangelists have different presentations of Jesus in their Gospels. -

Japheth and Balaam

Redemption 304: Further Study on Japheth and Balaam biblestudying.net Brian K. McPherson and Scott McPherson Copyright 2012 Melchizedek (Shem), Japheth, and Balaam Summary of Relevant Information from Genesis Regarding Melchizedek and Abraham This exploratory paper assumes the conclusions of section three of our “Priesthood and the Kinsman Redeemer” study which identifies Melchizedek as Noah’s son Shem. Melchizedek was priest of Jerusalem (Salem) and possibly of the region in general. Shem was granted dominion over all the Canaanites by Noah. Genesis 9:22 And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw the nakedness of his father, and told his two brethren without. 23 And Shem and Japheth took a garment, and laid it upon both their shoulders, and went backward, and covered the nakedness of their father; and their faces were backward, and they saw not their father’s nakedness. 24 And Noah awoke from his wine, and knew what his younger son had done unto him. 25 And he said, Cursed be Canaan; a servant of servants shall he be unto his brethren. 26 And he said, Blessed be the LORD God of Shem; and Canaan shall be his servant. Melchizedek is clearly presented as a king. And Abraham clearly pays tithes or tribute to this king after a victory in battle. Genesis 14:18 And Melchizedek king of Salem brought forth bread and wine: and he was the priest of the most high God. 19 And he blessed him, and said, Blessed be Abram of the most high God, possessor of heaven and earth: 20 And blessed be the most high God, which hath delivered thine enemies into thy hand. -

LALIBELA Ethiopia, Africa

LALIBELA Ethiopia, Africa Unesco World Heritage Site in 1978 According to oral tradition, Ethiopia was founded by Ethiopicus, the great-great- grandson of Noah. His son, named Axumai, founded the capital of Axum and a dynasty that reigned for 97 generations. His last queen, named Makeda (Queen of Sheba). She visited King Solomon in Jerusalem and returned pregnant. Her son Menelik I was the first of the Solomonic dynasty which ruled almost uninterruptedly until 1974 when Haile Selassie was deposed. Within the latter dynasty the best known king was Lalibela (1133-1173) and according to tradition, he travelled to Jerusalem just before the city fell into Muslim hands and then decided to create a new Jerusalem in Ethiopia, giving his name to this city of churches. The churches of Lalibela were built between the 7th and 13th centuries. They are carved from single blocks of red basaltic rock, without bricks, wood or mortar. Chisels, axes and shovels were used to carve into the porous volcanic surface. There are 4 free-standing churches and the others are attached to the rock. The churches were linked by passages and over time a multitude of hollows and caves were cut into the rock around the temples. These cavities were used as tombs (bones can still be seen) and as dwellings for hermits. Why were the churches built "underground"? • Where Lalibela is, there is no stone or wood to build with, there is only the rock where the churches were excavated. • The temples were hidden from the eyes of the Arabs, who were harassing Ethiopia at the time. -

Moses -- Exodus 2:1-10 David and Goliath (I Samuel 17:1-58)

Moses -- Exodus 2:1-10 Exodus 2:1-10 New International Version (NIV) The Birth of Moses 2 Now a man of the tribe of Levi married a Levite woman, 2 and she became pregnant and gave birth to a son. When she saw that he was a fine child, she hid him for three months. 3 But when she could hide him no longer, she got a papyrus basket[a] for him and coated it with tar and pitch. Then she placed the child in it and put it among the reeds along the bank of the Nile. 4 His sister stood at a distance to see what would happen to him. 5 Then Pharaoh’s daughter went down to the Nile to bathe, and her attendants were walking along the riverbank. She saw the basket among the reeds and sent her female slave to get it. 6 She opened it and saw the baby. He was crying, and she felt sorry for him. “This is one of the Hebrew babies,” she said. 7 Then his sister asked Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?” 8 “Yes, go,” she answered. So the girl went and got the baby’s mother. 9 Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, “Take this baby and nurse him for me, and I will pay you.” So the woman took the baby and nursed him. 10 When the child grew older, she took him to Pharaoh’s daughter and he became her son. -

Chapter Three MASSAH and MERIBAH

Chapter Three MASSAH AND MERIBAH In this chapter I increase the specificity further by analysing the legends of the waters that flow from a mountain or are associ ated with the names Massah and Meribah (Exod 17:1-7; Num 20:1-13). For comparative purposes, the traditions of Beer (Num 21:16-18) and Marah (Exod 15:23-26) are discussed first, even though they properly belong with the thirst stories of chapter one. Beer The simplest account of the miraculous production of water in the wilderness in the days of the desert wanderings of Israel is Num 21:16-18: 16And thence [they traveled] to Beer [Well]; that is the well where Yahweh said to Moses: "Gather the people, and I will give them water."1 17Then the chil dren of Israel sang this song: "Rise, well, ,,Z they sanl to it. 18"0 well which the princes dug, which the leaders of the people 4 hewed with scepter [and] staff."5 What can we make of this fragment? It is often described as archaic,6 but such a dating largely reflects past scholarship's predisposition to regard short poems as the original form of Israelite tradition; the somewhat murky contents perhaps contri bute to this evaluation. The lack of relative pronoun in 18a and of conjunction in 18c are insufficient grounds for assigning the poem an early date, especially since its present form seems gar bled. In fact, the fragment is undatable, but its relation to the Massah-Meribah tradition is clear. Yahweh commands Moses to gather the people, and he himself will provide water. -

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr

Notes on Numbers 202 1 Edition Dr. Thomas L. Constable TITLE The title the Jews used in their Hebrew Old Testament for this book comes from the fifth word in the book in the Hebrew text, bemidbar: "in the wilderness." This is, of course, appropriate since the Israelites spent most of the time covered in the narrative of Numbers in the wilderness. The English title "Numbers" is a translation of the Greek title Arithmoi. The Septuagint translators chose this title because of the two censuses of the Israelites that Moses recorded at the beginning (chs. 1—4) and toward the end (ch. 26) of the book. These "numberings" of the people took place at the beginning and end of the wilderness wanderings and frame the contents of Numbers. DATE AND WRITER Moses wrote Numbers (cf. Num. 1:1; 33:2; Matt. 8:4; 19:7; Luke 24:44; John 1:45; et al.). He apparently wrote it late in his life, across the Jordan from the Promised Land, on the Plains of Moab.1 Moses evidently died close to 1406 B.C., since the Exodus happened about 1446 B.C. (1 Kings 6:1), the Israelites were in the wilderness for 40 years (Num. 32:13), and he died shortly before they entered the Promised Land (Deut. 34:5). There are also a few passages that appear to have been added after Moses' time: 12:3; 21:14-15; and 32:34-42. However, it is impossible to say how much later. 1See the commentaries for fuller discussions of these subjects, e.g., Gordon J. -

Religion and Faith in Jordan Ahlan Wa Sahlan

A Guide to Religion and Faith in Jordan Ahlan Wa Sahlan Welcome to the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, founded by carved from rock over 2000 years ago, it also offers much more King Abdullah I, and currently ruled by King Abdullah II son of for the modern traveller, from the Jordan Valley, fertile and ever the late King Hussein. Over the years, Jordan has grown into a changing, to the remote desert canyons, immense and still. stable, peaceful and modern country. Whether you are a thrill seeker, a historian, or you just want to relax, Jordan is the place for you. While Jordan is known for the ancient Nabataean city of Petra, Content Biblical Jordan 2 Bethany Beyond the Jordan 4 Madaba 6 Mount Nebo 8 Mukawir 10 Tall Mar Elias 11 Anjara 11 Pella 12 As-Salt 12 Umm Qays 13 Umm Ar-Rasas 14 Jerash 15 Petra 16 Hisban 17 The Dead Sea & Lot’s Cave 18 Amman 20 Aqaba 21 The King’s Highway 22 Letters of Acknowledgement 23 Itineraries 24 Jordan Tourism Board: Is open Sunday to Thursday (08:00-17:00). 1 BIBLICAL JORDAN The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan has proven home to some of the most LQpXHQWLDO%LEOLFDOOHDGHUVRIWKHSDVW$EUDKDP-RE0RVHV5XWK(OLMDK -RKQWKH%DSWLVW-HVXV&KULVWDQG3DXOWRQDPHDIHZ$VWKHRQO\DUHD ZLWKLQ WKH +RO\ /DQG YLVLWHG E\ DOO RI WKHVH JUHDW LQGLYLGXDOV -RUGDQ breathes with the histories recorded in the Holy Bible. 7KURXJK WKH ZRUGV RI WKH SURSKHWV $EUDKDP -RE DQG 0RVHV LQ WKH %LEOH V2OG7HVWDPHQWWKLVODQGLVZKHUH*RGoUVWPDQLIHVWHG+LPVHOI WR PDQ +HUH $GDP DQG (YH PD\ KDYH VWRRG LQ WKH IRUPHU *DUGHQ RI(GHQLQDQDUHDDORQJWKHQRUWKZHVWEDQNRIWKH5LYHU-RUGDQQRZ known as Beysan (Beth-shean). -

Adam and Seth in Arabic Medieval Literature: The

ARAM, 22 (2010) 509-547. doi: 10.2143/ARAM.22.0.2131052 ADAM AND SETH IN ARABIC MEDIEVAL LITERATURE: THE MANDAEAN CONNECTIONS IN AL-MUBASHSHIR IBN FATIK’S CHOICEST MAXIMS (11TH C.) AND SHAMS AL-DIN AL-SHAHRAZURI AL-ISHRAQI’S HISTORY OF THE PHILOSOPHERS (13TH C.)1 Dr. EMILY COTTRELL (Leiden University) Abstract In the middle of the thirteenth century, Shams al-Din al-Shahrazuri al-Ishraqi (d. between 1287 and 1304) wrote an Arabic history of philosophy entitled Nuzhat al-Arwah wa Raw∂at al-AfraÌ. Using some older materials (mainly Ibn Nadim; the ∑iwan al-Ìikma, and al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik), he considers the ‘Modern philosophers’ (ninth-thirteenth c.) to be the heirs of the Ancients, and collects for his demonstration the stories of the ancient sages and scientists, from Adam to Proclus as well as the biographical and bibliographical details of some ninety modern philosophers. Two interesting chapters on Adam and Seth have not been studied until this day, though they give some rare – if cursory – historical information on the Mandaeans, as was available to al-Shahrazuri al-Ishraqi in the thirteenth century. We will discuss the peculiar historiography adopted by Shahrazuri, and show the complexity of a source he used, namely al-Mubashshir ibn Fatik’s chapter on Seth, which betray genuine Mandaean elements. The Near and Middle East were the cradle of a number of legends in which Adam and Seth figure. They are presented as forefathers, prophets, spiritual beings or hypostases emanating from higher beings or created by their will. In this world of multi-millenary literacy, the transmission of texts often defied any geographical boundaries. -

Subject List

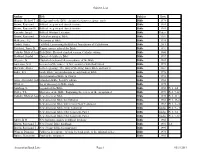

Subject List Author Title Subject Date Murphy, Richard T.A. Background to the Bible: An introduction to scripture study Bible 1978 Brown, Raymond Biblical exegesis and church doctrine Bible 1985 Brown, Raymond E. Biblical exegesis and church doctrine Bible 1985 Koterski, Joseph Biblical Wisdom Literature Bible Video Brown, Raymond Critical meaning of Bible Bible 1981 McKenzie, J L Dictionary of Bible Bible 1995 Corbitt, Sonja Fulfilled: Uncovering the Biblical foundations of Catholicism Bible 2018 Pritchard, James B. Harper concise atlas of the Bible Bible 1991 Catholic Biblical AssnHoly Bible: Revised standard version, Catholic edition Bible 1966 Stoddard, Sandol Illustrated children's Bible Bible 1997 Wigoder, G. Illustrated dictionary & concordance of the Bible Bible 2005 Anderson, Neil In search of the source: A first encounter with God's word Bible 1992 McGrath, Alister In the beginning: The story of the King James Bible and how it … Bible 2001 Baker, K S Inside Bible : an introduction to each book of Bible Bible 1998 Interpretation of Bible in Church Bible 1993 Jones, Alexander (Ed.)Jerusalem Bible: Reader's edition Bible 1968 Wald, O Joy of discovery in Bible study Bible 1975 Ginzberg, L. Legends of the Bible Bible 1956 Pt 1, 1-6 Dailey, T.L. Mysteries of the Bible: Explaining the secrets of the unexplained Bible 1999 Pt 2, 7-12 Catholic Biblical AssnNew American Bible Bible 1970 Pt 3, 13-18 New American Bible for Catholics Bible 1968 Pt 4, 19-24 New American Bible with revised New Testament Bible 1987 Pt 1, 1 – 6 New American Bible: New Testament Bible Audio Pt 2, 7 – 12 New American Bible: Old Testament, Part 1 Bible Audio Pt 1, 1-6 New American Bible: Old Testament, Part 2 Bible Audio Pt 2, 7-12 Ahern, B M New horizons; studies in biblical theology Bible 1965 Brown, Raymond, J. -

A Biographical Study of Aaron

Scholars Crossing Old Testament Biographies A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible 10-2018 A Biographical Study of Aaron Harold Willmington Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Willmington, Harold, "A Biographical Study of Aaron" (2018). Old Testament Biographies. 4. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ot_biographies/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the A Biographical Study of Individuals of the Bible at Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Old Testament Biographies by an authorized administrator of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Aaron CHRONOLOGICAL SUMMARY I. His service A. For Moses 1. Aaron was a spokesman for Moses in Egypt. a. He was officially appointed by God (Exod. 4:16). b. At the time of his calling he was 83 (Exod. 7:6-7). c. He accompanied Moses to Egypt (Exod. 4:27-28). d. He met with the enslaved Israelites (Exod. 4:29). e. He met with Pharaoh (Exod. 5:1). f. He was criticized by the Israelites, who accused him of giving them a killing work burden (Exod. 5:20-21). g. He cast down his staff in front of Pharaoh, and it became a serpent (Exod. 7:10). h. He saw his serpent swallow up the serpents produced by Pharaoh's magicians (Exod. 7:12). i. He raised up his staff and struck the Nile, causing it to be turned into blood (Exod. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title One Law for Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5qn8t4jf Author Spielman, David Benjamin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in African Studies by David Benjamin Spielman 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS One Law For Us All: A History of Social Cohesion through Shared Legal Tradition Among the Abrahamic Faiths in Ethiopia by David Benjamin Spielman Master of Arts in African Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Ghislaine E. Lydon, Chair This thesis historically traces the development and interactions of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam in Ethiopia. This analysis of the interactions between the Abrahamic faiths is primarily concerned with identifying notable periods of social cohesion in an effort to contest mainstream narratives that often pit the three against each other. This task is undertaken by incorporating a comparative analysis of the Ethiopian Christian code, the Fetha Nagast (Law of Kings), with Islamic and Judaic legal traditions. Identifying the common threads weaved throughout the Abrahamic legal traditions demonstrates how the historical development and periods of social cohesion in Ethiopia were facilitated. ii The thesis of David Benjamin Spielman is approved. Allen F. -

Box List of Moses Gaster's Working Papers at the John Rylands

Box list of Moses Gaster’s working papers at the John Rylands University Library, Manchester Maria Haralambakis, 2012 This box list provides a guide to a specific segment of the wide ranging Gaster collection at The John Rylands Library, part of the University of Manchester, namely the contents of thirteen boxes of ‘Gaster Papers’. It is intended to help researchers to search for items of interest in this extensive but largely untapped collection. The box list is a work in progress and descriptions of the first six boxes are at present more detailed than those of boxes seven to thirteen. Most of the work in preparation for this box list has been undertaken in the context of a postdoctoral research fellowship funded by the Rothschild Foundation (Hanadiv) Europe at the Centre for Jewish Studies in the University of Manchester (September 2011– August 2012). Biographical history Moses Gaster was born in Bucharest (Romania) to a privileged Jewish family in 1856. His mother's name was Phina Judith Rubinstein. His father, Abraham Emanuel Gaster (d. 1926), was the commercial attaché of the Dutch consulate. Gaster went to Germany in 1873 to pursue philological studies at the University of Breslau, which he combined with studying for his Rabbinic degree at the Rabbinic Seminary of Breslau. He defended his doctoral thesis at the University of Leipzig. After his studies, in 1881, he returned to Romania and lectured in Romanian language and literature at the University of Bucharest. He also officiated as an inspector of secondary schools (from 1883) and an examiner of teachers (from 1884).