THE USE of SCRIPTURE in the LETTER of JUDE Felix Opoku

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Canon of Scripture October 7, 2019

How to Study the Bible – The Canon of Scripture October 7, 2019 Recommended Resources “Scripture Alone” – James White “The Canon of Scripture” – Samuel Waldron Introduction – What is the Purpose of God’s Word? To accomplish His purpose Isa 55:9-11 For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are my ways higher than your ways and my thoughts than your thoughts. (10) "For as the rain and the snow come down from heaven and do not return there but water the earth, making it bring forth and sprout, giving seed to the sower and bread to the eater, (11) so shall my word be that goes out from my mouth; it shall not return to me empty, but it shall accomplish that which I purpose, and shall succeed in the thing for which I sent it. To equip believers 2Ti 3:16-17 All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, (17) that the man of God may be competent, equipped for every good work. To defend the church Acts 20:26-30 Therefore I testify to you this day that I am innocent of the blood of all of you, (27) for I did not shrink from declaring to you the whole counsel of God . (28) Pay careful attention to yourselves and to all the flock, in which the Holy Spirit has made you overseers, to care for the church of God, which he obtained with his own blood. (29) I know that after my departure fierce wolves will come in among you, not sparing the flock ; (30) and from among your own selves will arise men speaking twisted things, to draw away the disciples after them. -

A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature Harry E

Ouachita Baptist University Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita Graduate Theses Archives and Special Collections 1967 A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature Harry E. Woodall Ouachita Baptist University Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/grad_theses Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christianity Commons, Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons, and the Sociology of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Woodall, Harry E., "A Study of the Sin and Death of Moses in Biblical Literature" (1967). Graduate Theses. 31. http://scholarlycommons.obu.edu/grad_theses/31 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons @ Ouachita. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A STUDY OF THE SIN AND DFATH OF MOSES IN BIBLICAL LITERATURE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Ouachita Baptist University Arkadelphia, Arkansas In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Harry E. Woodall August, 1967 A STUDY OF THE SIN AND DFATH OF MOSES IN BIBLICAL LITERATURE APPROVED: I L.t;z -~ >tuJ.!uJr) Major rofessor iv CHAPTER PAGE The Devil's Claim of Moses in Jude ••••• 42 A Critical Review of Jude • • • • • • • • 42 The Purpose of Jude • • • • • • • • • • • 47 The Interpretation of Jude 9 • • • • • • • 47 The Appearance of Moses to Christ in Mark • 49 Witness of the Other Passages • • • • • • 50 General Background of the Transfiguration 51 A Critical Analysis of the Transfiguration • • • • • • • • • • • • 52 Interpretation of the Transfiguration • • 58 Moses and Elijah in the Transfiguration • 60 A Belief in the Return of Moses • • • • • 64 Moses as a Heavenly Being • • • • • • • • 64 A New Testament Theology of Moses •••• 65 Moses in Extra-Biblical Literature •••• 67 IV. -

Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies

0 Pseudepigrapha Bibliographies Bibliography largely taken from Dr. James R. Davila's annotated bibliographies: http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/~www_sd/otpseud.html. I have changed formatting, added the section on 'Online works,' have added a sizable amount to the secondary literature references in most of the categories, and added the Table of Contents. - Lee Table of Contents Online Works……………………………………………………………………………………………...02 General Bibliography…………………………………………………………………………………...…03 Methodology……………………………………………………………………………………………....03 Translations of the Old Testament Pseudepigrapha in Collections…………………………………….…03 Guide Series…………………………………………………………………………………………….....04 On the Literature of the 2nd Temple Period…………………………………………………………..........04 Literary Approaches and Ancient Exegesis…………………………………………………………..…...05 On Greek Translations of Semitic Originals……………………………………………………………....05 On Judaism and Hellenism in the Second Temple Period…………………………………………..…….06 The Book of 1 Enoch and Related Material…………………………………………………………….....07 The Book of Giants…………………………………………………………………………………..……09 The Book of the Watchers…………………………………………………………………………......….11 The Animal Apocalypse…………………………………………………………………………...………13 The Epistle of Enoch (Including the Apocalypse of Weeks)………………………………………..…….14 2 Enoch…………………………………………………………………………………………..………..15 5-6 Ezra (= 2 Esdras 1-2, 15-16, respectively)……………………………………………………..……..17 The Treatise of Shem………………………………………………………………………………..…….18 The Similitudes of Enoch (1 Enoch 37-71)…………………………………………………………..…...18 The -

Syllabus and Text

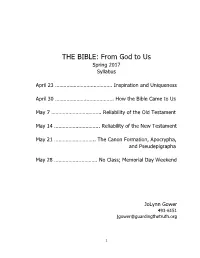

THE BIBLE: From God to Us Spring 2017 Syllabus April 23 …………………………………. Inspiration and Uniqueness April 30 ………………….………………. How the Bible Came to Us May 7 …………………………….. Reliability of the Old Testament May 14 ………………………….. Reliability of the New Testament May 21 ……………………….. The Canon Formation, Apocrypha, and Pseudepigrapha May 28 ………………..………. No Class; Memorial Day Weekend JoLynn Gower 493-6151 [email protected] 1 INSPIRATION AND UNIQUENESS The Bible continues to be the best selling book in the World. But between 1997 and 2007, some speculate that Harry Potter might have surpassed the Bible in sales if it were not for the Gideons. This speaks to the world in which we now find ourselves. There is tremendous interest in things that are “spiritual” but much less interest in the true God revealed in the Bible. The Bible never tries to prove that God exists. He is everywhere assumed to be. Read Exodus 3:14 and write what you learn: ____________________________ _________________________________________________________________ The God who calls Himself “I AM” inspired a divinely authorized book. The process by which the book resulted is “God-breathed.” The Spirit moved men who wrote God-breathed words. Read the following verses and record your thoughts: 2 Timothy 3:16-17__________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ Do a word study on “scripture” from the above passage, and write the results here: ____________________________________________________________ _________________________________________________________________ -

Note: the Hebrew Scriptures at the Time of Christ Were Combined and Arranged Differently Than Our Old Testament Today

Understanding Apocrypha, Part 2 [Note: The Hebrew Scriptures at the time of Christ were combined and arranged differently than our Old Testament today. Two common arrangements had either 22 or 24 books. The consensus among scholars is that the 22 or 24 were identical to the 39 in the Protestant Old Testament today.] Common Proposals: 1. The Old Testament canon must not have been clear because Jewish rabbis argued about which books should be included. “The actual discussions of the contents of Scripture in ancient Judaism show no trace of an expanded canon that included the Apocrypha.” (Blomberg, 49) “The only debates reflected among the rabbis in early post-Christian centuries were whether a few of the twenty-two or twenty-four books … merited inclusion, not whether any others deserved to join them.” (Blomberg, 52) 2. Since the library at Qumran (the cave settlement where the Dead Sea Scrolls were discovered, which was inhabited during the centuries before Christ) contained more than just biblical books, Judaism must have accepted other books. We know little about this unusual Jewish sect that was hiding away at Qumran. If you came to my library in my office you would find many books besides the Bible, but that would not imply anything about my view of the canon. We do know that the residents at Qumran produced commentaries on thirteen biblical books but not on any apocryphal books, and that only three of the books in the Roman Catholic apocrypha were found there. 3. Since the early Greek translations of the Old Testament include some apocryphal books, and since Jesus and the apostles quoted from those Greek translations extensively, they must have approved of those apocryphal books. -

Aramaic Studies the Leading Journal for Aramaic Language and Literature Brill.Com/Arst

Aramaic Studies The Leading Journal for Aramaic Language and Literature brill.com/arst Instructions for Authors Scope Aramaic Studies (ARST) brings all aspects of the various forms of Aramaic and their literatures together to help shape the field of Aramaic Studies. The journal, which has been the main platform for Targum and Peshitta Studies for some time, is now also the main outlet for the study of all Aramaic dialects, including the language and literatures of Old Aramaic, Achaemenid Aramaic, Palmyrene, Nabataean, Qumran Aramaic, Mandaic, Syriac, Rabbinic Aramaic, and Neo-Aramaic. Ethical and Legal Conditions The publication of a manuscript in a peer-reviewed work is expected to follow standards of ethical behaviour for all parties involved in the act of publishing: authors, editors, and reviewers. Authors, editors, and reviewers should thoroughly acquaint themselves with Brill’s publication ethics, which may be downloaded here: brill.com/page/ethics/publication-ethics-cope-compliance. Online Submission Aramaic Studies uses online submission only. Authors should submit their manuscript online via the Editorial Manager (EM) online submission system at: editorialmanager.com/arst. First-time users of EM need to register first. Go to the website and click on the "Register Now" link in the login menu. Enter the information requested. During registration, you can fill in your username and password. If you should forget this username and password, click on the "send login details" link in the login section, and enter your e-mail address exactly as you entered it when you registered. Your access codes will then be e-mailed to you. Prior to submission, authors are encouraged to read the entire ‘Instructions for Authors’. -

Jude 5-16) - Part One “Sin Never Ruins but Where It Reigns.” ~ William Secker, Puritan

A Study of Jude From Bad to “Badder”: How God will Address the Internal Corruption (Jude 5-16) - part one “Sin never ruins but where it reigns.” ~ William Secker, Puritan I. Introduction Jude spends the next twelve verses addressing the false teachers. Utilizing various Old Testament and inter-testamental Jewish writings, Jude compares these ungodly individuals to those who sinned in the past. In so doing, our author highlights several important principles. As aptly noted by one commentator, “God’s judgments in the past and the prophetic testimony all bear witness to the coming and the doom of the heretics who have invaded the church” (Green, Jude and 2 Peter, 61). This study will observe verses 5-10. We will not only observe the vital truths Jude seeks to convey to his readers, we will also discuss the use of Jude’s non-canonical traditions in relationship to the rest of Scripture. II. From Bad to “Badder” (vv. 5-16) A. The Diabolic Trio and the Problem of Sin (vv. 5-8) v. 5 - The call to remember serves as a vital tool for moral instruction (see 1 Thess 1:5; 2:1, 2, 5, 11). The fate of those who pursued unrighteousness should serve as a contestant reminder of the consequences of sin. 1. Generation of the Exodus (v. 5) Various English versions differ on who exactly is accomplishing the deliverance of the Israelites and then later punishes those who are rebellious. The standard rendering is “Lord” (e.g., KJV, NIV, NASB). This reading is in keeping with the Old Testament’s portrayal of the Lord as the one who brought the people out of the land of Egypt (see Exod 16:6; 18:1; Deut 26:8). -

The Apocrypha and the Book of Mormon

The Apocrypha and the Book of Mormon In the light of the Dead Sea Scrolls, all the Apocryphal writings must be read again with a new respect. Today the correctness of Section 91 of the Doctrine and Covenants as an evaluation of the Apocrypha is vindicated with the acceptance of an identical view by scholars of every persuasion, though a hundred years ago the proposition set forth in the Doctrine and Covenants seemed preposterous. What all the apocryphal writings have in common with each other and with the scriptures is the Apocalyptic or eschatological theme. This theme is nowhere more fully and clearly set forth than in the Book of Mormon. Fundamental to this theme is the belief in a single prophetic tradition handed down from the beginning of the world in a series of dispensations, but hidden from the world in general and often conned to certain holy writings. Central to the doctrine is the Divine Plan behind the creation of the world which is expressed in all history and revealed to holy prophets from time to time. History unfolds in repeating cycles in order to provide all men with a fair and equal test in the time of their probation. Every dispensation, or “Visitation,” it was taught, is followed by an apostasy and a widespread destruction of the wicked, and ultimately by a refreshing or a new visitation. What Are the Apocrypha? The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has directed the attention of the learned as never before to the study of that vast and neglected eld of literature known as the Apocrypha. -

The Assumption of Moses : Translated from the Latin Sixth Century Ms., The

THE ASSUMPTION r OF MOSES R.H, CHARLE \ STUDIA IN THE LIBRARY of VICTORIA UNIVERSITY Toronto PRESS OPINIONS. THE APOCALYPSE OF BARUCH. Translated from the Syriac. BY REV, R. H. CHARLES. Crown 8vo, cloth, price Js. 6d. net. " Mr. Charles s last work will have a hearty welcome from students of Syriac whose interest is linguistic, and from theological students who value of have learned the Jewish and Christian pseudepigraphy ; and the educated general reader will find much of high interest in it, regard being had to its date and its theological standpoint." Record. "Mr. Charles has in this work followed up the admirable editions of other pieces of apocalyptic literature with an edition equally admirable. Some of the notes on theological or other points of special interest are very full and instructive. The whole work is an honour to English scholarship. The work before us is one that no future student of the apocalyptic literature will be able to neglect, and students of the New Testament or the contemporary Jewish thought will find much to interest them in it." Primitive Methodist Quarterly Review. "As is intimated in the title-page, the Syriac text, based on ten MSS., from which the Epistle of Baruch is translated, is included in the volume. The learned footnotes which accompany the translation throughout will be found most helpful to the reader. Indeed, nothing seems to have been left undone which could make this ancient writing intelligible to the student." Scotsman. To say that this is the edition of the Apocalypse of Baruch is to say nothing. -

Pseudepigrapha: an Account of Certain Apocryphal Sacred Writings of the Jews and Early Christians

Pseudepigrapha: An Account of Certain Apocryphal Sacred Writings of the Jews and Early Christians Author(s): Deane, William John (1823-1895) Publisher: Grand Rapids, MI: Christian Classics Ethereal Library Description: In Pseudepigrapha, William Deane surveys the Psalter of Solomon, the Book of Enoch, the Assumption of Moses, the Apocalypse of Baruch, the Testaments of the Twelve Patri- archs, the Book of Jubilees, the Ascension of Isaiah, and the Sibylline Oracles.These books are pseudepigraphous, which means they were falsely authored before and during the early Christian era under famous names to promote publicity. These books were never included in the Jewish Canonical Scriptures and are examined less frequently than the other apocryphal writings. The pseudepigraphical texts are organ- ized into four different groups: lyrical, apocalyptical and prophetical, legendary, and mixed. Deane intended this book to give a succinct account of these controversial books for readers who are not familiar with them. Despite their biblical inauthenticity, these books can greatly enrich our knowledge of the ancient Jewish belief system. Emmalon Davis CCEL Staff Writer Subjects: The Bible Old Testament Special parts of the Old Testament i Contents Title Page 1 Preface 2 Original Table of Contents 3 Introduction 4 I. Lyrical 17 The Psalter of Solomon 18 II. Apocalyptical and Prophetical. 32 The Book of Enoch 33 The Assumption of Moses 57 The Apocalypse of Baruch 77 The Testaments of the Twelve Patriarchs. 94 Legendary 110 The Book of Jubilees 111 The Ascension of Isaiah 134 IV. Mixed 154 The Sibylline Oracles. 155 Subject Index 191 Indexes 198 Index of Scripture References 199 Greek Words and Phrases 203 Hebrew Words and Phrases 209 Latin Words and Phrases 210 Index of Pages of the Print Edition 214 ii This PDF file is from the Christian Classics Ethereal Library, www.ccel.org. -

Following Moses: an Investigation Into the Prophetic Discourse of the First Century C

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Following Moses: An Investigation Into The Prophetic Discourse Of The First Century C. E Virginia L. Wayland University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Wayland, Virginia L., "Following Moses: An Investigation Into The Prophetic Discourse Of The First Century C. E" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2632. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2632 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2632 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Following Moses: An Investigation Into The Prophetic Discourse Of The First Century C. E Abstract ABSTRACT FOLLOWING MOSES: AN INVESTIGATION INTO THE PROPHETIC DISCOURSE OF THE FIRST CENTURY C.E. This dissertation informs current discussions of the apparent transformation of the concepts of prophets and prophecy within Judaism of the Second Temple period by examining the application of the Law of the Prophet (Deut 18:15-22) within two first century C.E. texts, the Testament of Moses and the Liber Antiquitatum Biblicarum of Pseudo-Philo. Combining scholarly study of ancient Biblical interpretation and of legal and historical narrative, the study examines the successors of Moses as an umbrella concept in discursive competition between centers of human and textual authority. The study was designed to be comparative, identifying key intermediaries, settings, and audiences for divine communication and presence in two characteristic literary forms of the Second Temple - pseudepigraphy and rewritten Bible. Since the two texts in focus reflect significantly different pseudepigraphy and textual genre, I treat them separately, using Philo of Alexandria and Josephus' Antiquities as well as parallel canonical texts to establish a field of comparison. -

A Reevaluation of the Structure and Function of 2 Maccabees 7 and Its Text-Critical Implications

Studia Antiqua Volume 7 Number 1 Article 9 April 2009 A Reevaluation of the Structure and Function of 2 Maccabees 7 and its Text-Critical Implications Daniel O. McClellan Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Biblical Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation McClellan, Daniel O. "A Reevaluation of the Structure and Function of 2 Maccabees 7 and its Text-Critical Implications." Studia Antiqua 7, no. 1 (2009). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol7/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A Reevaluation of the Structure and Function of 2 Maccabees 7 and its text-critical Implications Daniel O. MCClellan ver the years 2 Maccabees has been subjected to all manner of critical Oanalysis. The primary concerns have been related to the date and prov- enance of the book, its historicity and chronology compared to 1 Maccabees, and its overall form and function.1 Recently source critics have been at the 1. The first major work is C. Grimm, “Das zweite, dritte, und vierte Buch der Mac- cabäer, vierte Lieferung,” in Kurzgefasstes exegetisches Handbuch zu den Apokryphen des Alten Testaments (ed. O.F. Fritische; Leipzig: S. Hirzel, 1857). During the mid-19th century, schol- arship began to grant preeminence to 1 Maccabees as the more historical (and thus valuable) of the first two Maccabean texts (see I.