Principles and Parameters and Government and Binding Syntactic Theory Winter Semester 2009/2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

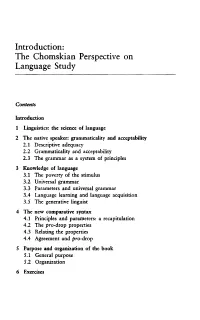

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms. -

Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic To cite this version: Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic. Introduction: Complex Adpo- sitions and Complex Nominal Relators. Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Dejan Stosic, Elena Smirnova. Complex Adpositions in European Languages : A Micro-Typological Approach to Com- plex Nominal Relators, 65, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-30, 2020, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology, 978-3-11-068664-7. 10.1515/9783110686647-001. halshs-03087872 HAL Id: halshs-03087872 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03087872 Submitted on 24 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova & Dejan Stosic Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard CNRS, ENS & Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle; PSL Lattice laboratory, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 1 rue Maurice Arnoux, 92120 Montrouge, France [email protected] -

501 Grammar & Writing Questions 3Rd Edition

501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 3rd Edition ® NEW YORK Copyright © 2006 LearningExpress, LLC. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by LearningExpress, LLC, New York. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 501 grammar & writing questions.—3rd ed. p. cm. ISBN 1-57685-539-2 1. English language—Grammar—Examinations, questions, etc. 2. English language— Rhetoric—Examinations, questions, etc. 3. Report writing—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Title: 501 grammar and writing questions. II. Title: Five hundred one grammar and writing questions. III. Title: Five hundred and one grammar and writing questions. PE1112.A15 2006 428.2'076—dc22 2005035266 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Third Edition ISBN 1-57685-539-2 For more information or to place an order, contact LearningExpress at: 55 Broadway 8th Floor New York, NY 10006 Or visit us at: www.learnatest.com Contents INTRODUCTION vii SECTION 1 Mechanics: Capitalization and Punctuation 1 SECTION 2 Sentence Structure 11 SECTION 3 Agreement 29 SECTION 4 Modifiers 43 SECTION 5 Paragraph Development 49 SECTION 6 Essay Questions 95 ANSWERS 103 v Introduction his book—which can be used alone, along with another writing-skills text of your choice, or in com- bination with the LearningExpress publication, Writing Skills Success in 20 Minutes a Day—will give Tyou practice dealing with capitalization, punctuation, basic grammar, sentence structure, organiza- tion, paragraph development, and essay writing. It is designed to be used by individuals working on their own and for teachers or tutors helping students learn or review basic writing skills. -

Estonian and Latvian Verb Government Comparison

TARTU UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ESTONIAN AND GENERAL LINGUISTICS DEPARTMENT OF ESTONIAN AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE Miķelis Zeibārts ESTONIAN AND LATVIAN VERB GOVERNMENT COMPARISON Master thesis Supervisor Dr. phil Valts Ernštreits and co-supervisor Mg. phil Ilze Tālberga Tartu 2017 Table of contents Preface ............................................................................................................................... 5 1. Method of research .................................................................................................... 8 2. Description of research sources and theoretical literature ......................................... 9 2.1. Research sources ................................................................................................ 9 2.2. Theoretical literature ........................................................................................ 10 3. Theoretical research background ............................................................................. 12 3.1. Cases in Estonian and Latvian .......................................................................... 12 3.1.1. Estonian noun cases .................................................................................. 12 3.1.2. Latvian noun cases .................................................................................... 13 3.2. The differences and similarities between Estonian and Latvian cases ............. 14 3.2.1. The differences between Estonian and Latvian case systems ................... 14 3.2.2. The similarities -

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC

On Object Shift, Scrambling, and the PIC Peter Svenonius University of Tromsø and MIT* 1. A Class of Movements The displacements characterized in (1-2) have received a great deal of attention. (Boldface in the gloss here is simply to highlight the alternation.) (1) Scrambling (exx. from Bergsland 1997: 154) a. ... gan nagaan slukax igaaxtakum (Aleut) his.boat out.of seagull.ABS flew ‘... a seagull flew out of his boat’ b. ... quganax hlagan kugan husaqaa rock.ABS his.son on.top.of fell ‘... a rock fell on top of his son’1 (2) Object Shift (OS) a. Hann sendi sem betur fer bréfi ni ur. (Icelandic) he sent as better goes the.letter down2 b. Hann sendi bréfi sem betur fer ni ur. he sent the.letter as better goes down (Both:) ‘He fortunately sent the letter down’ * I am grateful to the University of Tromsø Faculty of Humanities for giving me leave to traipse the globe on the strength of the promise that I would write some papers, and to the MIT Department of Linguistics & Philosophy for welcoming me to breathe in their intellectually stimulating atmosphere. I would especially like to thank Noam Chomsky, Norvin Richards, and Juan Uriagereka for discussing parts of this work with me while it was underway, without implying their endorsement. Thanks also to Kleanthes Grohmann and Ora Matushansky for valuable feedback on earlier drafts, and to Ora Matushansky and Elena Guerzoni for their beneficient editorship. 1 According to Bergsland (pp. 151-153), a subject preceding an adjunct tends to be interpreted as definite (making (1b) unusual), and one following an adjunct tends to be indefinite; this is broadly consistent with the effects of scrambling cross-linguistically. -

A Minimalist Analysis of English Topicalization: a Phase-Based Cartographic Complementizer Phrase (CP) Perspective

J UOEH 38( 4 ): 279-289(2016) 279 [Original] A Minimalist Analysis of English Topicalization: A Phase-Based Cartographic Complementizer Phrase (CP) Perspective Hiroyoshi Tanaka* Department of English, School of Medicine, University of Occupational and Environmental Health, Japan. Yahata- nishi-ku, Kitakyushu 807-8555, Japan Abstract : Under the basic tenet that syntactic derivation offers an optimal solution to both phonological realization and semantic interpretation of linguistic expression, the recent minimalist framework of syntactic theory claims that the basic unit for the derivation is equivalent to a syntactic propositional element, which is called a phase. In this analysis, syntactic derivation is assumed to proceed at phasal projections that include Complementizer Phrases (CP). However, there have been pointed out some empirical problems with respect to the failure of multiple occurrences of discourse-related elements in the CP domain. This problem can be easily overcome if the alternative approach in the recent minimalist perspective, which is called Cartographic CP analysis, is adopted, but this may raise a theoretical issue about the tension between phasality and four kinds of functional projections assumed in this analysis (Force Phrase (ForceP), Finite Phrase (FinP), Topic Phrase (TopP) and Focus Phrase (FocP)). This paper argues that a hybrid analysis with these two influential approaches can be proposed by claiming a reasonable assumption that syntacti- cally requisite projections (i.e., ForceP and FinP) are phases and independently constitute a phasehood with relevant heads in the derivation. This then enables us to capture various syntactic properties of the Topicalization construction in English. Our proposed analysis, coupled with some additional assumptions and observations in recent minimalist studies, can be extended to incorporate peculiar properties in temporal/conditional adverbials and imperatives. -

1 a Microparametric Approach to the Head-Initial/Head-Final Parameter

A microparametric approach to the head-initial/head-final parameter Guglielmo Cinque Ca’ Foscari University, Venice Abstract: The fact that even the most rigid head-final and head-initial languages show inconsistencies and, more crucially, that the very languages which come closest to the ideal types (the “rigid” SOV and the VOS languages) are apparently a minority among the languages of the world, makes it plausible to explore the possibility of a microparametric approach for what is often taken to be one of the prototypical examples of macroparameter, the ‘head-initial/head-final parameter’. From this perspective, the features responsible for the different types of movement of the constituents of the unique structure of Merge from which all canonical orders derive are determined by lexical specifications of different generality: from those present on a single lexical item, to those present on lexical items belonging to a specific subclass of a certain category, or to every subclass of a certain category, or to every subclass of two or more, or all, categories, (always) with certain exceptions.1 Keywords: word order, parameters, micro-parameters, head-initial, head-final 1. Introduction. An influential conjecture concerning parameters, subsequent to the macro- parametric approach of Government and Binding theory (Chomsky 1981,6ff and passim), is that they can possibly be “restricted to formal features [of functional categories] with no interpretation at the interface” (Chomsky 1995,6) (also see Borer 1984 and Fukui 1986). This conjecture has opened the way to a microparametric approach to differences among languages, as well as to differences between related words within one and the same language (Kayne 2005,§1.2). -

Remarks on Binding Theory

Remarks on Binding Theory Carl Pollard Ohio State University Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar Department of Informatics, University of Lisbon Stefan Muller¨ (Editor) 2005 CSLI Publications pages 561–577 http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/HPSG/2005 Pollard, Carl. 2005. Remarks on Binding Theory. In Muller,¨ Stefan (Ed.), Pro- ceedings of the 12th International Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar, Department of Informatics, University of Lisbon, 561–577. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications. Abstract We propose some reformulations of binding principle A that build on re- cent work by Pollard and Xue, and by Runner et al. We then turn to the thorny issue of the status of indices, in connection with the seemingly simpler Principle B. We conclude that the notion of index is fundamen- tally incoherent, and suggest some possible approaches to eliminating them as theoretical primitives. One possibility is to let logical variables take up the explanatory burden borne by indices, but this turns out to be fraught with difficulties. Another approach, which involves returning to the idea that referentially dependent expressions denote identity func- tions (as proposed, independently, by Pollard and Sag and by Jacobson) seerms to hold more promise. 1 Introduction As formulated by Chomsky (1986), binding theory (hereafter BT) constrained in- dexings, which were taken to be assignments of indices to the NPs in a phrase. What an index was was irrelevant; what mattered was that they partitioned all the NPs in a phrase into equivalence classes. Phrases, in turn, were taken to be trees of the familiar kind and the binding constraints themselves were couched in terms of tree-configurational notions such as government, c-command (or m-command), chain, and maximal projection.