A Lexical-Functional Analysis of Predicate Topicalization in German

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

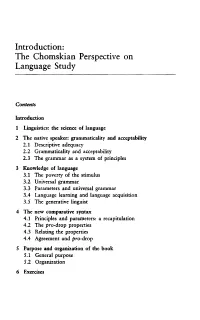

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

A Theory of Generalized Pied-Piping Sayaka Funakoshi, Doctor Of

ABSTRACT Title of dissertation: A Theory of Generalized Pied-Piping Sayaka Funakoshi, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Professor Howard Lasnik Department of Linguistics The purpose of this thesis is to construct a theory to derive how pied-piping of formal features of a moved element takes place, by which some syntactic phenomena related to φ-features can be accounted for. Ura (2001) proposes that pied-piping of formal-features of a moved element is constrained by an economy condition like relativized minimality. On the basis of Ura’s (2001) proposal, I propose that how far an element that undergoes movement can carry its formal features, especially focusing on φ-features in this thesis, is determined by two conditions, a locality condition on the generalized pied-piping and an anti-locality condition onmovement. Given the proposed analysis, some patterns of so-called wh-agreement found in Bantu languages can be explained and with the assumption that φ-features play an role for binding, presence or absence of WCO effects in various languages can be derived without recourse to A/A-distinctions.¯ ATHEORYOFGENERALIZEDPIED-PIPING by Sayaka Funakoshi Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Howard Lasnik, Chair/Advisor Professor Norbert Hornstein Professor Omer Preminger Professor Steven Ross Professor Juan Uriagereka c Copyright by ! Sayaka Funakoshi 2015 Acknowledgments First and foremost, I would like to thank my advisor Howard Lasnik for his patience, support and encouragement. -

Particle Topicalization and German Clause Structure

Erschienen in: The Journal of Comparative Germanic Linguistics ; 19 (2016), 2. - S. 109-141 https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10828-016-9080-y Particle topicalization and German clause structure Andreas Trotzke1 • Stefano Quaglia2 Abstract In this paper, we provide a comprehensive account of the phenomenon of topicalizing verb particles in German. Based on the data we discuss, we argue that only a version of the Split-CP hypothesis for the German clause can account for the observations. Section 1 critiques previous accounts of particle topicalization and discusses some properties of particles that are potentially relevant to topicalization. We conclude that a particle’s ability to be topicalized depends more on its ability to be contrasted with other particles than on the semantic autonomy of the particle per se. Section 2 discusses unexpected cases of non-contrastable particles in the left periphery. In this context, we introduce a previously unnoticed phenomenon in which particle verbs denoting strongly emotionally evaluated situations allow their particles to be topicalized, even if the particle does not receive a contrastive interpretation. In Sect. 3, we show that an elaborated syntax of the German left periphery of the kind argued for in cartographic approaches is uniquely able to predict the distribution of topicalized particles. Keywords Contrast Á Emphasis Á Expressive content Á Left periphery Á Particle verbs Á Topicalization & Andreas Trotzke [email protected] Stefano Quaglia stefano.quaglia@uni konstanz.de 1 Center for the Study -

Why Germanic VP-Topicalization Does Not Induce Verb Doubling

Why Germanic VP-topicalization does not induce verb doubling Johannes Hein [email protected] University of Potsdam CGSW 32 Trondheim, 13–15 September 2017 Partly funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinscha (DFG), Collaborative Research Centre SFB 1287, Project C05. J. Hein Germanic VP-topicalization lacks verb doubling 13–15 Sep 2017 1 / 60 Proposal Proposal I argue that the absence of verb doubling with verb phrase topicalization in Germanic languages despite them having V-to-T(-to-C) movement is a consequence of the language-specific ordering of the two operations copy deletion (CD, Nunes 2004; Trinh 2011) and head movement (HM, Chomsky 1995; Platzack 2013) both of which take place post-syntactically. While verb doubling languages like Hebrew, Spanish, or Polish order head movement before copy deletion which allows the verb to escape the lower VP copy, CD applies before HM in Germanic languages deleting the lower VP copy thereby bleeding verb movement. J. Hein Germanic VP-topicalization lacks verb doubling 13–15 Sep 2017 2 / 60 Introduction In a number of languages it is possible to displace the verb phrase into the le periphery of the clause. Usually, this displacement is associated with a topic or focus interpretation and some kind of contrast. Examples from Polish (1-a), Hebrew (1-b), German (1-c), and Norwegian (1-d) are given below. (1) a. [VP wypić herbatę] (to) Marek chce , ale nie chce jej robić drink.inf tea to Marek wants but not wants it make ‘As for drinking tea, Marek wants to drink it, but he doesn’t want to make it.’ (Polish, Joanna Zaleska p.c.) b. -

Syntax-Semantics Interface

: Syntax-Semantics Interface http://cognet.mit.edu/library/erefs/mitecs/chierchia.html Subscriber : California Digital Library » LOG IN Home Library What's New Departments For Librarians space GO REGISTER Advanced Search The CogNet Library : References Collection : Table of Contents : Syntax-Semantics Interface «« Previous Next »» A commonplace observation about language is that it consists of the systematic association of sound patterns with meaning. SYNTAX studies the structure of well-formed phrases (spelled out as sound sequences); SEMANTICS deals with the way syntactic structures are interpreted. However, how to exactly slice the pie between these two disciplines and how to map one into the other is the subject of controversy. In fact, understanding how syntax and semantics interact (i.e., their interface) constitutes one of the most interesting and central questions in linguistics. Traditionally, phenomena like word order, case marking, agreement, and the like are viewed as part of syntax, whereas things like the meaningfulness of a well-formed string are seen as part of semantics. Thus, for example, "I loves Lee" is ungrammatical because of lack of agreement between the subject and the verb, a phenomenon that pertains to syntax, whereas Chomky's famous "colorless green ideas sleep furiously" is held to be syntactically well-formed but semantically deviant. In fact, there are two aspects of the picture just sketched that one ought to keep apart. The first pertains to data, the second to theoretical explanation. We may be able on pretheoretical grounds to classify some linguistic data (i.e., some native speakers' intuitions) as "syntactic" and others as "semantic." But we cannot determine a priori whether a certain phenomenon is best explained in syntactic or semantics terms. -

Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto De Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic

Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic To cite this version: Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova, Dejan Stosic. Introduction: Complex Adpo- sitions and Complex Nominal Relators. Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Dejan Stosic, Elena Smirnova. Complex Adpositions in European Languages : A Micro-Typological Approach to Com- plex Nominal Relators, 65, De Gruyter Mouton, pp.1-30, 2020, Empirical Approaches to Language Typology, 978-3-11-068664-7. 10.1515/9783110686647-001. halshs-03087872 HAL Id: halshs-03087872 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-03087872 Submitted on 24 Dec 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Benjamin Fagard, José Pinto de Lima, Elena Smirnova & Dejan Stosic Introduction: Complex Adpositions and Complex Nominal Relators Benjamin Fagard CNRS, ENS & Paris Sorbonne Nouvelle; PSL Lattice laboratory, Ecole Normale Supérieure, 1 rue Maurice Arnoux, 92120 Montrouge, France [email protected] -

HISTORICAL SYNTAX from Obligatory WH-Movement to Optional WH-In-Situ in Labourdin Basque MAIA DUGUINE ARITZ IRURTZUN University

HISTORICAL SYNTAX From obligatory WH -movement to optional WH -in-situ in Labourdin Basque Maia Duguine Aritz Irurtzun University of the Basque Country UPV/EHU CNRS-IKER In this article, we analyze the nature and origin of a new wh -question strategy employed by young speakers of Labourdin Basque. We argue that this new strategy implies a parametric change: while Basque has always been a bona fide wh -movement language, these new construc - tions are instances of wh -in-situ and display the syntactic and semantic properties and patterns of in-situ wh -questions in French. We analyze the emergence of this new strategy as being due to the combination of three factors: (i) the abundance of structurally ambiguous wh -questions in the pri - mary linguistic data, (ii) the change in the sociolinguistic profile of bilingual Basque-French speakers, and (iii) an economy bias for movementless derivations. Keywords : wh -movement, wh -in-situ, parameters, change, language contact, economy, Basque 1. Introduction: the wh-question strategy in standard basque . The Basque language is spoken on both sides of the Franco-Spanish border and is in a diglossic sit - uation with respect to both French and Spanish (see Moseley 2010, Eusko Jaurlaritza 2013, inter alia). In terms of grammar, it is a head-final language. The ‘neutral’ word order of constituents (the word order of an out-of-the-blue sentence) is subject-indirect object-direct object-verb (S-IO-DO-V) (see e.g. Laka 1993 , Elordieta 2001). Regard- ing interrogatives, wh -questions in Basque are generally analyzed as involving wh - movement, followed by movement of the verb, which results in a strict adjacency between the wh -phrase and the verbal complex. -

501 Grammar & Writing Questions 3Rd Edition

501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 501 GRAMMAR AND WRITING QUESTIONS 3rd Edition ® NEW YORK Copyright © 2006 LearningExpress, LLC. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by LearningExpress, LLC, New York. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data 501 grammar & writing questions.—3rd ed. p. cm. ISBN 1-57685-539-2 1. English language—Grammar—Examinations, questions, etc. 2. English language— Rhetoric—Examinations, questions, etc. 3. Report writing—Examinations, questions, etc. I. Title: 501 grammar and writing questions. II. Title: Five hundred one grammar and writing questions. III. Title: Five hundred and one grammar and writing questions. PE1112.A15 2006 428.2'076—dc22 2005035266 Printed in the United States of America 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Third Edition ISBN 1-57685-539-2 For more information or to place an order, contact LearningExpress at: 55 Broadway 8th Floor New York, NY 10006 Or visit us at: www.learnatest.com Contents INTRODUCTION vii SECTION 1 Mechanics: Capitalization and Punctuation 1 SECTION 2 Sentence Structure 11 SECTION 3 Agreement 29 SECTION 4 Modifiers 43 SECTION 5 Paragraph Development 49 SECTION 6 Essay Questions 95 ANSWERS 103 v Introduction his book—which can be used alone, along with another writing-skills text of your choice, or in com- bination with the LearningExpress publication, Writing Skills Success in 20 Minutes a Day—will give Tyou practice dealing with capitalization, punctuation, basic grammar, sentence structure, organiza- tion, paragraph development, and essay writing. It is designed to be used by individuals working on their own and for teachers or tutors helping students learn or review basic writing skills. -

Estonian and Latvian Verb Government Comparison

TARTU UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF ESTONIAN AND GENERAL LINGUISTICS DEPARTMENT OF ESTONIAN AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE Miķelis Zeibārts ESTONIAN AND LATVIAN VERB GOVERNMENT COMPARISON Master thesis Supervisor Dr. phil Valts Ernštreits and co-supervisor Mg. phil Ilze Tālberga Tartu 2017 Table of contents Preface ............................................................................................................................... 5 1. Method of research .................................................................................................... 8 2. Description of research sources and theoretical literature ......................................... 9 2.1. Research sources ................................................................................................ 9 2.2. Theoretical literature ........................................................................................ 10 3. Theoretical research background ............................................................................. 12 3.1. Cases in Estonian and Latvian .......................................................................... 12 3.1.1. Estonian noun cases .................................................................................. 12 3.1.2. Latvian noun cases .................................................................................... 13 3.2. The differences and similarities between Estonian and Latvian cases ............. 14 3.2.1. The differences between Estonian and Latvian case systems ................... 14 3.2.2. The similarities