1 a Microparametric Approach to the Head-Initial/Head-Final Parameter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lisa Pearl LING200, Summer Session I, 2004 Syntax – Sentence Structure

Lisa Pearl LING200, Summer Session I, 2004 Syntax – Sentence Structure I. Syntax A. Gives us the ability to say something new with old words. Though you have seen all the words that I’m using in this sentence before, it’s likely you haven’t seen them put together in exactly this way before. But you’re perfectly capable of understanding the sentence, nonetheless. A. Structure: how to put words together. A. Grammatical structure: a way to put words together which is allowed in the language. a. I often paint my nails green or blue. a. *Often green my nails I blue paint or. II. Syntactic Categories A. How to tell which category a word belongs to: look at the type of meaning the word has, the type of affixes which can adjoin to the word, and the environments you find the word in. A. Meaning: tell lexical category from nonlexical category. a. lexical – meaning is fairly easy to paraphrase i. vampire ≈ “night time creature that drinks blood” i. dark ≈ “without much light” i. drink ≈ “ingest a liquid” a. nonlexical – meaning is much harder to pin down i. and ≈ ?? i. the ≈ ?? i. must ≈ ?? a. lexical categories: Noun, Verb, Adjective, Adverb, Preposition i. N: blood, truth, life, beauty (≈ entities, objects) i. V: bleed, tell, live, remain (≈ actions, sensations, states) i. A: gory, truthful, riveting, beautiful (≈ property/attribute of N) 1. gory scene 1. riveting tale i. Adv: sharply, truthfully, loudly, beautifully (≈ property/attribute of V) 1. speak sharply 1. dance beautifully i. P: to, from, inside, around, under (≈ indicates path or position w.r.t N) 1. -

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

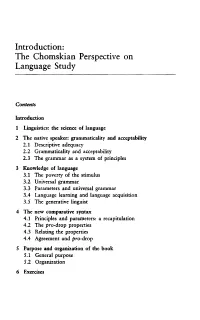

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

Logophoricity in Finnish

Open Linguistics 2018; 4: 630–656 Research Article Elsi Kaiser* Effects of perspective-taking on pronominal reference to humans and animals: Logophoricity in Finnish https://doi.org/10.1515/opli-2018-0031 Received December 19, 2017; accepted August 28, 2018 Abstract: This paper investigates the logophoric pronoun system of Finnish, with a focus on reference to animals, to further our understanding of the linguistic representation of non-human animals, how perspective-taking is signaled linguistically, and how this relates to features such as [+/-HUMAN]. In contexts where animals are grammatically [-HUMAN] but conceptualized as the perspectival center (whose thoughts, speech or mental state is being reported), can they be referred to with logophoric pronouns? Colloquial Finnish is claimed to have a logophoric pronoun which has the same form as the human-referring pronoun of standard Finnish, hän (she/he). This allows us to test whether a pronoun that may at first blush seem featurally specified to seek [+HUMAN] referents can be used for [-HUMAN] referents when they are logophoric. I used corpus data to compare the claim that hän is logophoric in both standard and colloquial Finnish vs. the claim that the two registers have different logophoric systems. I argue for a unified system where hän is logophoric in both registers, and moreover can be used for logophoric [-HUMAN] referents in both colloquial and standard Finnish. Thus, on its logophoric use, hän does not require its referent to be [+HUMAN]. Keywords: Finnish, logophoric pronouns, logophoricity, anti-logophoricity, animacy, non-human animals, perspective-taking, corpus 1 Introduction A key aspect of being human is our ability to think and reason about our own mental states as well as those of others, and to recognize that others’ perspectives, knowledge or mental states are distinct from our own, an ability known as Theory of Mind (term due to Premack & Woodruff 1978). -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Noun Phrase in the Text of Developing English Competencies Book for X Grade of Senior High School

A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF NOUN PHRASE IN THE TEXT OF DEVELOPING ENGLISH COMPETENCIES BOOK FOR X GRADE OF SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in Department of English by DIANA KUSUMA SARI A 320080287 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2012 A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF NOUN PHRASE IN THE TEXT OF DEVELOPING ENGLISH COMPENTENCIES BOOK FOR X GRADE OF SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL Diana Kusuma Sari A 320 080 287 Dra. Malikatul Laila, M. Hum. Nur Hidayat, S. Pd. English Department, School of Teacher Training and Education Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta (UMS) E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research deals with Noun Phrase in the genre text of Developing English Competencies book by Achmad Doddy. The aims of this research are to identify the constituent of the Noun Phrase and to describe the structural ambiguities of the Noun Phrase in the genre text. The type of this research is descriptive qualitative. The data source of this research is the genre text book by Achmad Doddy, Developing English Competencies Book. The researcher takes 145 data of noun phrase in sentences of Developing English Competencies Book. The method of collecting data is documentation and the steps are reading, indentifying, collecting and coding the data. The method of analyzing data is comparative method. The analysis of the data is by reffering to the context of syntax by using tree diagram in the theory of phrase structure rules then presenting phrase structure rules and phrase markers. This study shows the constituents of noun phrase in sentences used in genre text book. -

II Levels of Language

II Levels of language 1 Phonetics and phonology 1.1 Characterising articulations 1.1.1 Consonants 1.1.2 Vowels 1.2 Phonotactics 1.3 Syllable structure 1.4 Prosody 1.5 Writing and sound 2 Morphology 2.1 Word, morpheme and allomorph 2.1.1 Various types of morphemes 2.2 Word classes 2.3 Inflectional morphology 2.3.1 Other types of inflection 2.3.2 Status of inflectional morphology 2.4 Derivational morphology 2.4.1 Types of word formation 2.4.2 Further issues in word formation 2.4.3 The mixed lexicon 2.4.4 Phonological processes in word formation 3 Lexicology 3.1 Awareness of the lexicon 3.2 Terms and distinctions 3.3 Word fields 3.4 Lexicological processes in English 3.5 Questions of style 4 Syntax 4.1 The nature of linguistic theory 4.2 Why analyse sentence structure? 4.2.1 Acquisition of syntax 4.2.2 Sentence production 4.3 The structure of clauses and sentences 4.3.1 Form and function 4.3.2 Arguments and complements 4.3.3 Thematic roles in sentences 4.3.4 Traces 4.3.5 Empty categories 4.3.6 Similarities in patterning Raymond Hickey Levels of language Page 2 of 115 4.4 Sentence analysis 4.4.1 Phrase structure grammar 4.4.2 The concept of ‘generation’ 4.4.3 Surface ambiguity 4.4.4 Impossible sentences 4.5 The study of syntax 4.5.1 The early model of generative grammar 4.5.2 The standard theory 4.5.3 EST and REST 4.5.4 X-bar theory 4.5.5 Government and binding theory 4.5.6 Universal grammar 4.5.7 Modular organisation of language 4.5.8 The minimalist program 5 Semantics 5.1 The meaning of ‘meaning’ 5.1.1 Presupposition and entailment 5.2 -

A More Perfect Tree-Building Machine 1. Refining Our Phrase-Structure

Intro to Linguistics Syntax 2: A more perfect Tree-Building Machine 1. Refining our phrase-structure rules Rules we have so far (similar to the worksheet, compare with previous handout): a. S → NP VP b. NP → (D) AdjP* N PP* c. VP → (AdvP) V (NP) PP* d. PP → P NP e. AP --> (Deg) A f. AdvP → (Deg) Adv More about Noun Phrases Last week I drew trees for NPs that were different from those in the book for the destruction of the city • What is the difference between the two theories of NP? Which one corresponds to the rule (b)? • What does the left theory claim that the right theory does not claim? • Which is closer to reality? How did can we test it? On a related note: how many meanings does one have? 1) John saw a large pink plastic balloon, and I saw one, too. Let us improve our NP-rule: b. CP = Complementizer Phrase Sometimes we get a sentence inside another sentence: Tenors from Odessa know that sopranos from Boston sing songs of glory. We need to have a new rule to build a sentence that can serve as a complement of a verb, where C complementizer is “that” , “whether”, “if” or it could be silent (unpronounced). g. CP → C S We should also improve our rule (c) to be like the one below. c. VP → (AdvP) V (NP) PP* (CP) (says CP can co-occur with NP or PP) Practice: Can you draw all the trees in (2) using the amended rules? 2) a. Residents of Boston hear sopranos of renown at dusk. -

Semantic Types and Type-Shifting. Conjunction and Type Ambiguity

Partee and Borschev, Tarragona 3, April 15, 2005 Semantic Types and Type-shifting. Conjunction and Type Ambiguity. Noun Phrase Interpretation and Type-Shifting Principles. Barbara H. Partee, University of Massachusetts, Amherst Vladimir Borschev, VINITI, Russian Academy of Sciences, and Univ. of Massachusetts, Amherst [email protected], [email protected]; http://people.umass.edu/partee/ Universidad Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona, April 15, 2005 1. Linguistic background:....................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1. Categorial grammar and syntax-semantics correspondence: centrality of function-argument application . 1 1.2. Tensions among simplicity, generality, uniformity and flexiblity........................................................... 1 2. Conjunction and Type Ambiguity (from Partee & Rooth, 1983)....................................................................... 2 2.0. To be explained: cross-categorial distribution and meaning of ‘and’, ‘or’. .................................................2 2.1. Generalized conjunction.............................................................................................................................. 3 2.2. Repercussions on the type theory: against uniformity, for "simplicity" and type-shifting.......................... 3 2.3. Proposal:...................................................................................................................................................... -

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns

Toward a Shared Syntax for Shifted Indexicals and Logophoric Pronouns Mark Baker Rutgers University April 2018 Abstract: I argue that indexical shift is more like logophoricity and complementizer agreement than most previous semantic accounts would have it. In particular, there is evidence of a syntactic requirement at work, such that the antecedent of a shifted “I” must be a superordinate subject, just as the antecedent of a logophoric pronoun or the goal of complementizer agreement must be. I take this to be evidence that the antecedent enters into a syntactic control relationship with a null operator in all three constructions. Comparative data comes from Magahi and Sakha (for indexical shift), Yoruba (for logophoric pronouns), and Lubukusu (for complementizer agreement). 1. Introduction Having had an office next to Lisa Travis’s for 12 formative years, I learned many things from her that still influence my thinking. One is her example of taking semantic notions, such as aspect and event roles, and finding ways to implement them in syntactic structure, so as to advance the study of less familiar languages and topics.1 In that spirit, I offer here some thoughts about how logophoricity and indexical shift, topics often discussed from a more or less semantic point of view, might have syntactic underpinnings—and indeed, the same syntactic underpinnings. On an impressionistic level, it would not seem too surprising for logophoricity and indexical shift to have a common syntactic infrastructure. Canonical logophoricity as it is found in various West African languages involves using a special pronoun inside the finite CP complement of a verb to refer to the subject of that verb. -

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: the Principles of Language Structure

Linguistics 21N - Linguistic Diversity and Universals: The Principles of Language Structure Ben Newman March 1, 2018 1 What are we studying in this course? This course is about syntax, which is the subfield of linguistics that deals with how words and phrases can be combined to form correct larger forms (usually referred to as sentences). We’re not particularly interested in the structure of words (morphemes), sounds (phonetics), or writing systems, but instead on the rules underlying how words and phrases can be combined across different languages. These rules are what make up the formal grammar of a language. Formal grammar is similar to what you learn in middle and high school English classes, but is a lot more, well, formal. Instead of classifying words based on meaning or what they “do" in a sentence, formal grammars depend a lot more on where words are in the sentence. For example, in English class you might say an adjective is “a word that modifies a noun”, such as red in the phrase the red ball. A more formal definition of an adjective might be “a word that precedes a noun" or “the first word in an adjective phrase" where the adjective phrase is red ball. Describing a formal grammar involves writing down a lot of rules for a language. 2 I-Language and E-Language Before we get into the nitty-gritty grammar stuff, I want to take a look at two ways language has traditionally been described by linguists. One of these descriptions centers around the rules that a person has in his/her mind for constructing sentences.