Compendium of Irish Grammar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Perfect Tenses 8.Pdf

Name Date Lesson 7 Perfect Tenses Teaching The present perfect tense shows an action or condition that began in the past and continues into the present. Present Perfect Dan has called every day this week. The past perfect tense shows an action or condition in the past that came before another action or condition in the past. Past Perfect Dan had called before Ellen arrived. The future perfect tense shows an action or condition in the future that will occur before another action or condition in the future. Future Perfect Dan will have called before Ellen arrives. To form the present perfect, past perfect, and future perfect tenses, add has, have, had, or will have to the past participle. Tense Singular Plural Present Perfect I have called we have called has or have + past participle you have called you have called he, she, it has called they have called Past Perfect I had called we had called had + past participle you had called you had called he, she, it had called they had called CHAPTER 4 Future Perfect I will have called we will have called will + have + past participle you will have called you will have called he, she, it will have called they will have called Recognizing the Perfect Tenses Underline the verb in each sentence. On the blank, write the tense of the verb. 1. The film house has not developed the pictures yet. _______________________ 2. Fred will have left before Erin’s arrival. _______________________ 3. Florence has been a vary gracious hostess. _______________________ 4. Andi had lost her transfer by the end of the bus ride. -

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles Mcdonald All Rights Reserved. The

Copyright © 2014 Richard Charles McDonald All rights reserved. The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary has permission to reproduce and disseminate this document in any form by any means for purposes chosen by the Seminary, including, without, limitation, preservation or instruction. GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR __________________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary __________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________________ by Richard Charles McDonald December 2014 APPROVAL SHEET GRAMMATICAL ANALYSIS OF VARIOUS BIBLICAL HEBREW TEXTS ACCORDING TO A TRADITIONAL SEMITIC GRAMMAR Richard Charles McDonald Read and Approved by: __________________________________________ Russell T. Fuller (Chair) __________________________________________ Terry J. Betts __________________________________________ John B. Polhill Date______________________________ I dedicate this dissertation to my wife, Nancy. Without her support, encouragement, and love I could not have completed this arduous task. I also dedicate this dissertation to my parents, Charles and Shelly McDonald, who instilled in me the love of the Lord and the love of His Word. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS.............................................................................................vi LIST OF TABLES.............................................................................................................vii -

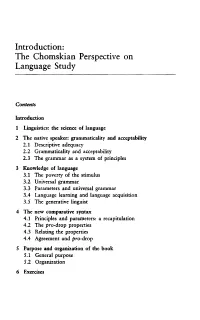

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

Ireland: Savior of Civilization?

Constructing the Past Volume 14 Issue 1 Article 5 4-2013 Ireland: Savior of Civilization? Patrick J. Burke Illinois Wesleyan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing Recommended Citation Burke, Patrick J. (2013) "Ireland: Savior of Civilization?," Constructing the Past: Vol. 14 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/constructing/vol14/iss1/5 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by editorial board of the Undergraduate Economic Review and the Economics Department at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Ireland: Savior of Civilization? Abstract One of the most important aspects of early medieval Ireland is the advent of Christianity on the island, accompanied by education and literacy. As an island removed from the Roman Empire, Ireland developed uniquely from the rest of western continental and insular Europe. Amongst those developments was that Ireland did not have a literary tradition, or more specifically a Latin literary tradition, until Christianity was introduced to the Irish. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

The Formation, Translation and Use of Participles in Latin, and the Nature of Relative Time

Chapter 23: Participles Chapter 23 covers the following: the formation, translation and use of participles in Latin, and the nature of relative time. At the end of the lesson we’ll review the vocabulary which you should memorize in this chapter. There are four important rules to remember in Chapter 23: (1) Latin has four participles: the present active, the future active; the perfect passive and the future passive. It lacks, however, a present passive participle (“being [verb]-ed”) and a perfect active participle (“having [verb]-ed”). (2) The perfect passive, future active and future passive participles belong to first/second declension. The present active participle belongs to third declension. (3) The verb esse has only a future active participle (futurus). It lacks both the present active and all passive participles. (4) Participles show relative time. What are participles? At heart, participles are verbs which have been turned into adjectives. Thus, technically participles are “verbal adjectives.” The first part of the word (parti-) means “part;” the second part (-cip-) means “take,” indicating that participles “partake, share” in the characteristics of both verbs and adjectives. In other words, the base of a participle is verbal, giving it some of the qualities of a verb, for instance, tense: it can indicate when the action is happening (now or then or later; i.e. present, past or future); conjugation: what thematic vowel will be used (e.g. -a- in first conjugation, -e- in second, and so on); voice: whether the word it’s attached to is acting or being acted upon (i.e. -

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> in ROMANCE and ENGLISH

<HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Diego A. de Acosta May 2006 © 2006 Diego A. de Acosta <HAVE + PERFECT PARTICIPLE> IN ROMANCE AND ENGLISH: SYNCHRONY AND DIACHRONY Diego A. de Acosta, Ph.D. Cornell University 2006 Synopsis: At first glance, the development of the Romance and Germanic have- perfects would seem to be well understood. The surface form of the source syntagma is uncontroversial and there is an abundant, inveterate literature that analyzes the emergence of have as an auxiliary. The “endpoints” of the development may be superficially described as follows (for English): (1) OE Ic hine ofslægenne hæbbe > Eng I have slain him The traditional view is that the source syntagma, <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle>, is structured [have [noun participle]], and that this syntagma undergoes change as have loses its possessive meaning. In this dissertation, I demonstrate that the traditional view is untenable and readdress two fundamental questions about the development of have-perfects: (i) how is the early ability of have to predicate possession connected with its later role in the perfect?; (ii) what are the syntactic structures and meanings of <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> before the emergence of the have-perfect? With corpus evidence, I show that that the surface string <have + noun.ACC + perfect participle> corresponds to three different structures in Old English and Latin; all of these survive into modern English and the Romance languages. -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

First Year Latin Texts and Methods in America

PL •? * H * " * • > * life,-. ' " * 4? W>' V » * 111 A1&- ii^-iv # «T <k. - . **J) ' ^* I* 'Mfc #^ • 1 I G IS. «J* | *'• * • iir V .T*: ' :4^sS Is T.JNTV. <JV ILLINOIS LIBRARY * Jf ^ w ^ v'^K * * * it lK ^ UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY Class ' Book Volumt M 1 20M 4^ *4 ^ 4 is ^ t * -4- 4, 4* liiiiiiil FIRST YEAR LATIN TEXTS AND METHODS IN AMERICA. THEIR HISTORY AND STATUS BY FRANK WATERS THOMASi A. B. Indiana University, 1905 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN LATIN IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1910 ^10 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY ENTITLED -FuxrtJr^ of BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF ^2Ji^^_JZx^-- qJLv~£c> n Charge of Major Work Head of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination 168020 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2013 http://archive.org/details/firstyearlatinteOOthom First Year Latin Texts and Methods in America: Their History and Status. The type of first year Latin book with which every high t school boy is familiar is a comparatively modem product. Men are yet living who learned their elementary Latin before any one had dared publish a beginner's book that dispensed with the use of a grammar in the first year. But in spite of this fact the number of such texts is legion. What educational problems have furnished the cause or at least the excuse for this multiplicity of texts, and what theories underlie the numerous attempts to solv<* these problems, I have tried in this investigation to determine. -

Language Reference

Language reference Unit 1 | Tenses Past perfect Present simple Use the past perfect to put events in the past in sequence. The past perfect indicates that the action it refers to happened before a Use the present simple reference to the past simple. 1 to talk about general facts, states, and situations I had heard from the locals that there were several interesting sites. The purpose of business is to make a profit. 2 to talk about regular or repeated actions, or permanent situations Past perfect continuous Jack works for Nissan. Use the past perfect continuous to refer to an action in progress before something else happened. 3 to talk about timetabled future events He was the one who had been working on the project, but his boss The meeting starts at 10.00. was the one who got all the credit. Present continuous Should Use the present continuous 1 Use should + infinitive to recommend something strongly. 1 to talk about an action in progress at the time of speaking / You should try that vegetarian restaurant on the river. writing 2 Use should + perfect infinitive to talk about a lost opportunity. I’m trying to get through to Jon Berks. You should have gone this morning – it was quite an interesting 2 to talk about a very current activity, taking place around the time meeting. of speaking 3 Use could / should + infinitive to predict. They are pushing the area for development. It could / should turn out to be quite an interesting conference. 3 to talk about fixed plans or arrangements in the future I am meeting the management committee on Friday. -

A Grammar of the Pali Language

PracticalPractical GrammarGrammar ofof thethe PaliPali LanguageLanguage by Charles Duroiselle HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. APracticalGrammar ofthe PŒliLanguage byCharlesDuroiselle ThirdEdition1997 Appendix 1 Here is a collection of dictionary definitions of some of the terms that can be found in this book Ablative: Of, relating to, or being a grammatical case indicating separation, direction away from, sometimes manner or agency, and the object of certain verbs. It is found in Latin and other Indo- European languages. Ablative absolute: In Latin grammar, an adverbial phrase syntactically independent from the rest of the sentence and containing a noun plus a participle, an adjective, or a noun, both in the ablative case. Accusative: Of, relating to, or being the case of a noun, pronoun, adjective, or participle that is the direct object of a verb or the object of certain prepositions. Active: Indicating that the subject of the sentence is performing or causing the action expressed by the verb. Used of a verb form or voice. Adjective: Any of a class of words used to modify a noun or other substantive by limiting, qualifying, or specifying and distinguished in English morphologically by one of several suffixes, such as -able, -ous, -er, and -est, or syntactically by position directly preceding a noun or nominal phrase, such as white in a white house. Aorist: A form of a verb in some languages, such as Classical Greek or Sanskrit, that in the indicative mood expresses past action.