Phrase Structure Directionality: Having a Few Choices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lisa Pearl LING200, Summer Session I, 2004 Syntax – Sentence Structure

Lisa Pearl LING200, Summer Session I, 2004 Syntax – Sentence Structure I. Syntax A. Gives us the ability to say something new with old words. Though you have seen all the words that I’m using in this sentence before, it’s likely you haven’t seen them put together in exactly this way before. But you’re perfectly capable of understanding the sentence, nonetheless. A. Structure: how to put words together. A. Grammatical structure: a way to put words together which is allowed in the language. a. I often paint my nails green or blue. a. *Often green my nails I blue paint or. II. Syntactic Categories A. How to tell which category a word belongs to: look at the type of meaning the word has, the type of affixes which can adjoin to the word, and the environments you find the word in. A. Meaning: tell lexical category from nonlexical category. a. lexical – meaning is fairly easy to paraphrase i. vampire ≈ “night time creature that drinks blood” i. dark ≈ “without much light” i. drink ≈ “ingest a liquid” a. nonlexical – meaning is much harder to pin down i. and ≈ ?? i. the ≈ ?? i. must ≈ ?? a. lexical categories: Noun, Verb, Adjective, Adverb, Preposition i. N: blood, truth, life, beauty (≈ entities, objects) i. V: bleed, tell, live, remain (≈ actions, sensations, states) i. A: gory, truthful, riveting, beautiful (≈ property/attribute of N) 1. gory scene 1. riveting tale i. Adv: sharply, truthfully, loudly, beautifully (≈ property/attribute of V) 1. speak sharply 1. dance beautifully i. P: to, from, inside, around, under (≈ indicates path or position w.r.t N) 1. -

The Equivalence and Shift Translation in Adjective Phrases of Indonesian

The Equivalence and Shift Translation in Adjective Phrases of Indonesian as Source Language to English as Target Language as Found in students Writing Descriptive Test of SMK Negeri 1 Lumbanjulu Sondang Manik, Ugaina Nuig Hasibuan [email protected] Abstract This study deals with the types of translation equivalence and shift adjective phrases and reason used translation equivalence and shift used on the students translation. This study used qualitative research. The data were collected by translate paper and observation students translation in the classroom. The data are taken from translate paper in the classroom. There are 268 translation equivalence and 211 translation shift. The data are analyzed based on types of translation equivalence ( linguistic, paradigmatic, stylistic and syntematic) and translation shift ( structure, class, intra system and unit). After analyzing the data, the types of translation equivalence and shift used on the students and offer was dominantly used in classroom translation. The total of translation equivalence 268 divide by the following Stylistic equivalence 64 and syntematic equivalence 204. The most dominant types of translation equivalence is syntematic equivalence. The total translation shift is 211 divide by the following by structure shift 18, class shift 129 and 64 unit shift. The most dominant types translation shift is class shift.The suggestion are to the English department students, to know the types of equivalence and shift translation, the English teachers in order to improve the ability of the students in translating descriptive text by using translation equivalence and shift especially adjective phrases and to other researchers are suggested to make research by equivalence and shift translation from different prespective. -

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

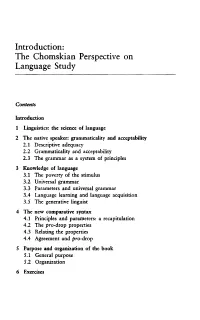

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

When Linearity Prevails Over Hierarchy in Syntax

When linearity prevails over hierarchy in syntax Jana Willer Golda, Boban Arsenijevic´b, Mia Batinic´c, Michael Beckerd, Nermina Cordalijaˇ e, Marijana Kresic´c, Nedzadˇ Lekoe, Franc Lanko Marusiˇ cˇf, Tanja Milicev´ g, Natasaˇ Milicevi´ c´g, Ivana Mitic´b, Anita Peti-Stantic´h, Branimir Stankovic´b, Tina Suligojˇ f, Jelena Tusekˇ h, and Andrew Nevinsa,1 aDivision of Psychology and Language Sciences, University College London, London WC1N 1PF, United Kingdom; bDepartment for Serbian language, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Nis,ˇ Nisˇ 18000, Serbia; cDepartment of Linguistics, University of Zadar, Zadar 23000, Croatia; dDepartment of Linguistics, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-4376; eDepartment of English, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Sarajevo, Sarajevo 71000, Bosnia and Herzegovina; fCenter for Cognitive Science of Language, University of Nova Gorica, Nova Gorica 5000, Slovenia; gDepartment of English Studies, Faculty of Philosophy, University of Novi Sad, Novi Sad 21000, Serbia; hDepartment of South Slavic languages and literatures, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Zagreb, Zagreb 10000, Croatia Edited by Barbara H. Partee, University of Massachusetts at Amherst, Amherst, MA, and approved November 27, 2017 (received for review July 21, 2017) Hierarchical structure has been cherished as a grammatical univer- show cases of agreement based on linear order, called “attrac- sal. We use experimental methods to show where linear order is tion,” with the plural complement of noun phrases (e.g., the key also a relevant syntactic relation. An identical methodology and to the cabinets are missing), a set of findings later replicated in design were used across six research sites on South Slavic lan- comprehension and across a variety of other languages and con- guages. -

The Function of Phrasal Verbs and Their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1991 The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals Brock Brady Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Applied Linguistics Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Brock, "The function of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts in technical manuals" (1991). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 4181. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.6065 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Brock Brady for the Master of Arts in Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (lESOL) presented March 29th, 1991. Title: The Function of Phrasal Verbs and their Lexical Counterparts in Technical Manuals APPROVED BY THE MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: { e.!I :flette S. DeCarrico, Chair Marjorie Terdal Thomas Dieterich Sister Rita Rose Vistica This study investigates the use of phrasal verbs and their lexical counterparts (i.e. nouns with a lexical structure and meaning similar to corresponding phrasal verbs) in technical manuals from three perspectives: (1) that such two-word items might be more frequent in technical writing than in general texts; (2) that these two-word items might have particular functions in technical writing; and that (3) 2 frequencies of these items might vary according to the presumed expertise of the text's audience. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

Processing Facilitation Strategies in OV and VO Languages: a Corpus Study

Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 2013. Vol.3, No.3, 252-258 Published Online September 2013 in SciRes (http://www.scirp.org/journal/ojml) http://dx.doi.org/10.4236/ojml.2013.33033 Processing Facilitation Strategies in OV and VO Languages: A Corpus Study Luis Pastor, Itziar Laka Department of Linguistics and Basque Studies, University of the Basque Country, Bilbao, Spain Email: [email protected] Received June 25th, 2013; revised July 25th, 2013; accepted August 2nd, 2013 Copyright © 2013 Luis Pastor, Itziar Laka. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Com- mons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, pro- vided the original work is properly cited. The present corpus study aimed to examine whether Basque (OV) resorts more often than Spanish (VO) to certain grammatical operations, in order to minimize the number of arguments to be processed before the verb. Ueno & Polinsky (2009) argue that VO/OV languages use certain grammatical resources with different frequencies in order to facilitate real-time processing. They observe that both OV and VO lan- guages in their sample (Japanese, Turkish and Spanish) have a similar frequency of use of subject pro- drop; however, they find that OV languages (Japanese, Turkish) use more intransitive sentences than VO languages (English, Spanish), and conclude this is an OV-specific strategy to facilitate processing. We conducted a comparative corpus study of Spanish (VO) and Basque (OV). Results show (a) that the fre- quency of use of subject pro-drop is higher in Basque than in Spanish; and (b) Basque does not use more intransitive sentences than Spanish; both languages have a similar frequency of intransitive sentences. -

Pronouns and Prosody in Irish&Sast;

PRONOUNS AND PROSODY IN IRISH* RYAN BENNETT Yale University EMILY ELFNER University of British Columbia JAMES MCCLOSKEY University of California, Santa Cruz 1. BACKGROUND One of the stranger properties of human language is the way in which it creates a bridge between two worlds which ought not be linked, and which seem not to be linked in any other species—a bridge linking the world of concepts, ideas and propositions with the world of muscular gestures whose outputs are perceivable. Because this link is made in us we can do what no other creature can do: we can externalize our internal and subjective mental states in ways that expose them to scrutiny by others and by ourselves. The existence of this bridge depends in turn on a system or systems which can take the complex structures used in cognition (hierarchical and recursive) and translate them step by step into the kinds of representations that our motor system knows how to deal with. In the largest sense, our goal in the research reported on here is to help better understand those systems and in particular the processes of serialization and flattening that make it possible to span the divide between the two worlds. In doing this, we study something which is of central importance to the question of what language is and how it might have emerged in our species. Establishing sequential order is, obviously, a key part of the process of serialization. And given the overall perspective just suggested, it is *Four of the examples cited in this paper (examples (35), (38a), (38b), and (38c)) have sound-files associated with them. -

Introduction, Page 1

Introduction, page 1 Introduction This book is concerned with how structure, meaning and communicative function interact in human languages. Language is a system of communicative social action in which grammatical structures are employed to express meaning in context. While all languages can achieve the same basic communicative ends, different languages use different linguistic means to achieve them, and an important aspect of these differences concerns the divergent ways syntax, semantics and pragmatics interact across languages. For example, the noun phrase referring to the entity being talked about (the ‘topic’) may be signalled by its position in the clause, by its grammatical function, by its morphological case, or by a particle in different languages, and moreover in some languages this marking may have grammatical consequences and in other languages it may not. The framework in which this investigation is to be carried out is Role and Reference Grammar [RRG].1 RRG grew out of an attempt to answer two basic questions, which were originally posed during the mid-1970’s: (i) what would linguistic theory look like if it were based on the analysis of Lakhota, Tagalog and Dyirbal, rather than on the analysis of English?, and (ii) how can the interaction of syntax, semantics and pragmatics in different grammatical systems best be captured and explained? Accordingly, RRG has developed descriptive tools and theoretical principles which are designed to expose this interaction and offer explanations for it. It posits three main representations: (1) a representation of the syntactic structure of sentences, which corresponds to the actual structural form of utterances, (2) a semantic representation representing important facets of the meaning of linguistic expressions, and (3) a representation of the information (focus) structure of the utterance, which is related to its communicative function. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Noun Phrase in the Text of Developing English Competencies Book for X Grade of Senior High School

A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF NOUN PHRASE IN THE TEXT OF DEVELOPING ENGLISH COMPETENCIES BOOK FOR X GRADE OF SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL PUBLICATION ARTICLE Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Getting Bachelor Degree of Education in Department of English by DIANA KUSUMA SARI A 320080287 SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION MUHAMMADIYAH UNIVERSITY OF SURAKARTA 2012 A SYNTACTIC ANALYSIS OF NOUN PHRASE IN THE TEXT OF DEVELOPING ENGLISH COMPENTENCIES BOOK FOR X GRADE OF SENIOR HIGH SCHOOL Diana Kusuma Sari A 320 080 287 Dra. Malikatul Laila, M. Hum. Nur Hidayat, S. Pd. English Department, School of Teacher Training and Education Muhammadiyah University of Surakarta (UMS) E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This research deals with Noun Phrase in the genre text of Developing English Competencies book by Achmad Doddy. The aims of this research are to identify the constituent of the Noun Phrase and to describe the structural ambiguities of the Noun Phrase in the genre text. The type of this research is descriptive qualitative. The data source of this research is the genre text book by Achmad Doddy, Developing English Competencies Book. The researcher takes 145 data of noun phrase in sentences of Developing English Competencies Book. The method of collecting data is documentation and the steps are reading, indentifying, collecting and coding the data. The method of analyzing data is comparative method. The analysis of the data is by reffering to the context of syntax by using tree diagram in the theory of phrase structure rules then presenting phrase structure rules and phrase markers. This study shows the constituents of noun phrase in sentences used in genre text book. -

A More Perfect Tree-Building Machine 1. Refining Our Phrase-Structure

Intro to Linguistics Syntax 2: A more perfect Tree-Building Machine 1. Refining our phrase-structure rules Rules we have so far (similar to the worksheet, compare with previous handout): a. S → NP VP b. NP → (D) AdjP* N PP* c. VP → (AdvP) V (NP) PP* d. PP → P NP e. AP --> (Deg) A f. AdvP → (Deg) Adv More about Noun Phrases Last week I drew trees for NPs that were different from those in the book for the destruction of the city • What is the difference between the two theories of NP? Which one corresponds to the rule (b)? • What does the left theory claim that the right theory does not claim? • Which is closer to reality? How did can we test it? On a related note: how many meanings does one have? 1) John saw a large pink plastic balloon, and I saw one, too. Let us improve our NP-rule: b. CP = Complementizer Phrase Sometimes we get a sentence inside another sentence: Tenors from Odessa know that sopranos from Boston sing songs of glory. We need to have a new rule to build a sentence that can serve as a complement of a verb, where C complementizer is “that” , “whether”, “if” or it could be silent (unpronounced). g. CP → C S We should also improve our rule (c) to be like the one below. c. VP → (AdvP) V (NP) PP* (CP) (says CP can co-occur with NP or PP) Practice: Can you draw all the trees in (2) using the amended rules? 2) a. Residents of Boston hear sopranos of renown at dusk. -

A Noun Phrase Parser of English Atro Voutilainen H Elsinki

A Noun Phrase Parser of English Atro Voutilainen H elsinki A bstract An accurate rule-based noun phrase parser of English is described. Special attention is given to the linguistic description. A report on a performance test concludes the paper. 1. Introduction 1.1 Motivation. A noun phrase parser is useful for several purposes, e.g. for index term generation in an information retrieval application; for the extraction of collocational knowledge from large corpora for the development of computational tools for language analysis; for providing a shallow but accurately analysed input for a more ambitious parsing system; for the discovery of translation units, and so on. Actually, the present noun phrase parser is already used in a noun phrase extractor called NPtool (Voutilainen 1993). 1.2. Constraint Grammar. The present system is based on the Constraint Grammar framework originally proposed by Karlsson (1990). A few characteristics of this framework are in order. • The linguistic representation is based on surface-oriented morphosyntactic tags that can encode dependency-oriented functional relations between words. • Parsing is reductionistic. All conventional analyses are provided as alternatives to each word by a context-free lookup mechanism, typically a morphological analyser. The parser itself seeks to discard all and only the contextually illegitimate alternative readings. What 'survives' is the parse.• • The system is modular and sequential. For instance, a grammar for the resolution of morphological (or part-of-speech) ambiguities is applied, before a syntactic module is used to introduce and then resolve syntactic ambiguities. 301 Proceedings of NODALIDA 1993, pages 301-310 • The parsing description is based on linguistic generalisations rather than probabilities.