The Dative Alternation in English As a Second Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Government and Binding Theory.1 I Shall Not Dwell on This Label Here; Its Significance Will Become Clear in Later Chapters of This Book

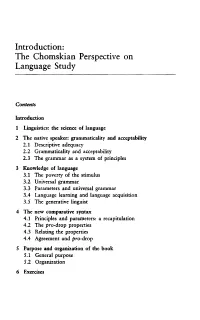

Introduction: The Chomskian Perspective on Language Study Contents Introduction 1 Linguistics: the science of language 2 The native speaker: grammaticality and acceptability 2.1 Descriptive adequacy 2.2 Grammaticality and acceptability 2.3 The grammar as a system of principles 3 Knowledge of language 3.1 The poverty of the stimulus 3.2 Universal grammar 3.3 Parameters and universal grammar 3.4 Language learning and language acquisition 3.5 The generative linguist 4 The new comparative syntax 4.1 Principles and parameters: a recapitulation 4.2 The pro-drop properties 4.3 Relating the properties 4.4 Agreement and pro-drop 5 Purpose and organization of the book 5.1 General purpose 5.2 Organization 6 Exercises Introduction The aim of this book is to offer an introduction to the version of generative syntax usually referred to as Government and Binding Theory.1 I shall not dwell on this label here; its significance will become clear in later chapters of this book. Government-Binding Theory is a natural development of earlier versions of generative grammar, initiated by Noam Chomsky some thirty years ago. The purpose of this introductory chapter is not to provide a historical survey of the Chomskian tradition. A full discussion of the history of the generative enterprise would in itself be the basis for a book.2 What I shall do here is offer a short and informal sketch of the essential motivation for the line of enquiry to be pursued. Throughout the book the initial points will become more concrete and more precise. By means of footnotes I shall also direct the reader to further reading related to the matter at hand. -

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish

On Binding Asymmetries in Dative Alternation Constructions in L2 Spanish Silvia Perpiñán and Silvina Montrul University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1. Introduction Ditransitive verbs can take a direct object and an indirect object. In English and many other languages, the order of these objects can be altered, giving as a result the Dative Construction on the one hand (I sent a package to my parents) and the Double Object Construction, (I sent my parents a package, hereafter DOC), on the other. However, not all ditransitive verbs can participate in this alternation. The study of the English dative alternation has been a recurrent topic in the language acquisition literature. This argument-structure alternation is widely recognized as an exemplar of the poverty of stimulus problem: from a limited set of data in the input, the language acquirer must somehow determine which verbs allow the alternating syntactic forms and which ones do not: you can give money to someone and donate money to someone; you can also give someone money but you definitely cannot *donate someone money. Since Spanish, apparently, does not allow DOC (give someone money), L2 learners of Spanish whose mother tongue is English have to become aware of this restriction in Spanish, without negative evidence. However, it has been noticed by Demonte (1995) and Cuervo (2001) that Spanish has a DOC, which is not identical, but which shares syntactic and, crucially, interpretive restrictions with the English counterpart. Moreover, within the Spanish Dative Construction, the order of the objects can also be inverted without superficial morpho-syntactic differences, (Pablo mandó una carta a la niña ‘Pablo sent a letter to the girl’ vs. -

3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement

e-Content Submission to INFLIBNET Subject name: Linguistics Paper name: Grammatical Categories Paper Coordinator name Ayesha Kidwai and contact: Module name A Framework for Grammatical Features -II Content Writer (CW) Ayesha Kidwai Name Email id [email protected] Phone 9968655009 E-Text Self Learn Self Assessment Learn More Story Board Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Features as Values 3. Contextual Features 3.1. Government 3.2 Agreement 4. A formal description of features and their values 5. Conclusion References 1 1. Introduction In this unit, we adopt (and adapt) the typology of features developed by Kibort (2008) (but not necessarily all her analyses of individual features) as the descriptive device we shall use to describe grammatical categories in terms of features. Sections 2 and 3 are devoted to this exercise, while Section 4 specifies the annotation schema we shall employ to denote features and values. 2. Features and Values Intuitively, a feature is expressed by a set of values, and is really known only through them. For example, a statement that a language has the feature [number] can be evaluated to be true only if the language can be shown to express some of the values of that feature: SINGULAR, PLURAL, DUAL, PAUCAL, etc. In other words, recalling our definitions of distribution in Unit 2, a feature creates a set out of values that are in contrastive distribution, by employing a single parameter (meaning or grammatical function) that unifies these values. The name of the feature is the property that is used to construct the set. Let us therefore employ (1) as our first working definition of a feature: (1) A feature names the property that unifies a set of values in contrastive distribution. -

Diachrony of Ergative Future

• THE EVOLUTION OF THE TENSE-ASPECT SYSTEM IN HINDI/URDU: THE STATUS OF THE ERGATIVE ALGNMENT Annie Montaut INALCO, Paris Proceedings of the LFG06 Conference Universität Konstanz Miriam Butt and Tracy Holloway King (Editors) 2006 CSLI Publications http://csli-publications.stanford.edu/ Abstract The paper deals with the diachrony of the past and perfect system in Indo-Aryan with special reference to Hindi/Urdu. Starting from the acknowledgement of ergativity as a typologically atypical feature among the family of Indo-European languages and as specific to the Western group of Indo-Aryan dialects, I first show that such an evolution has been central to the Romance languages too and that non ergative Indo-Aryan languages have not ignored the structure but at a certain point went further along the same historical logic as have Roman languages. I will then propose an analysis of the structure as a predication of localization similar to other stative predications (mainly with “dative” subjects) in Indo-Aryan, supporting this claim by an attempt of etymologic inquiry into the markers for “ergative” case in Indo- Aryan. Introduction When George Grierson, in the full rise of language classification at the turn of the last century, 1 classified the languages of India, he defined for Indo-Aryan an inner circle supposedly closer to the original Aryan stock, characterized by the lack of conjugation in the past. This inner circle included Hindi/Urdu and Eastern Panjabi, which indeed exhibit no personal endings in the definite past, but only gender-number agreement, therefore pertaining more to the adjectival/nominal class for their morphology (calâ, go-MSG “went”, kiyâ, do- MSG “did”, bola, speak-MSG “spoke”). -

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory

A PROLOG Implementation of Government-Binding Theory Robert J. Kuhns Artificial Intelligence Center Arthur D. Little, Inc. Cambridge, MA 02140 USA Abstrae_~t For the purposes (and space limitations) of A parser which is founded on Chomskyts this paper we only briefly describe the theories Government-Binding Theory and implemented in of X-bar, Theta, Control, and Binding. We also PROLOG is described. By focussing on systems of will present three principles, viz., Theta- constraints as proposed by this theory, the Criterion, Projection Principle, and Binding system is capable of parsing without an Conditions. elaborate rule set and subcategorization features on lexical items. In addition to the 2.1 X-Bar Theory parse, theta, binding, and control relations are determined simultaneously. X-bar theory is one part of GB-theory which captures eross-categorial relations and 1. Introduction specifies the constraints on underlying structures. The two general schemata of X-bar A number of recent research efforts have theory are: explicitly grounded parser design on linguistic theory (e.g., Bayer et al. (1985), Berwick and Weinberg (1984), Marcus (1980), Reyle and Frey (1)a. X~Specifier (1983), and Wehrli (1983)). Although many of these parsers are based on generative grammar, b. X-------~X Complement and transformational grammar in particular, with few exceptions (Wehrli (1983)) the modular The types of categories that may precede or approach as suggested by this theory has been follow a head are similar and Specifier and lagging (Barton (1984)). Moreover, Chomsky Complement represent this commonality of the (1986) has recently suggested that rule-based pre-head and post-head categories, respectively. -

TWO FORMS of "BE" in MALAYALAM1 Tara Mohanan and K.P

TWO FORMS OF "BE" IN MALAYALAM1 Tara Mohanan and K.P. Mohanan National University of Singapore 1. INTRODUCTION Malayalam has two verbs, uNTE and aaNE, recognized in the literature as copulas (Asher 1968, Variar 1979, Asher and Kumari 1997, among others). There is among speakers of Malayalam a clear, intuitively perceived meaning difference between the verbs. One strong intuition is that uNTE and aaNE correspond to the English verbs "have" and "be"; another is that they should be viewed as the "existential" and "equative" copulas respectively.2 However, in a large number of contexts, these verbs appear to be interchangeable. This has thwarted the efforts of a clear characterization of the meanings of the two verbs. In this paper, we will explore a variety of syntactic and semantic environments that shed light on the differences between the constructions with aaNE and uNTE. On the basis of the asymmetries we lay out, we will re-affirm the intuition that aaNE and uNTE are indeed equative and existential copulas respectively, with aaNE signaling the meaning of “x is an element/subset of y" and uNTE signaling the meaning of existence of an abstract or concrete entity in the fields of location or possession. We will show that when aaNE is interchangable with uNTE in existential clauses, its function is that of a cleft marker, with the existential meaning expressed independently by the case markers on the nouns. Central to our exploration of the two copulas is the discovery of four types of existential clauses in Malayalam, namely: Neutral: with the existential verb uNTE. -

MR Harley Miyagawa Syntax of Ditransitives

Syntax of Ditransitives Heidi Harley and Shigeru Miyagawa (in press, Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Linguistics) July 2016 Summary Keywords 1. Structure for the Two Internal Arguments 2. Underlying Order 3. Meaning Differences 4. Case, Clitic 5. The Structure of Ditransitives 6. Nominalization Asymmetries 6.1. A Morphological Account of the Nominalization Asymmetry 6.2. –kata Nominalization in Japanese and Myer’s Generalization 6.3 Selectional Accounts of the Nominalization Asymmetry 6.4 Applicative vs Small Clause Approaches to the DOC. 7. Constraints on the Dative/DOC Alternation 7.1 Morphological Constraints 7.2 Lexical Semantic Constraints 7.3 Information-Structural and Sentential Prosody Constraints 8. Overview and Prospects Further Reading References Summary Ditransitive predicates select for two internal arguments, and hence minimally entail the participation of three entities in the event described by the verb. Canonical ditranstive verbs include give, show and teach; in each case, the verb requires an Agent (a giver, shower or teacher, respectively), a Theme (the thing given, shown or taught) and a Goal (the recipient, viewer, or student). The property of requiring two internal arguments makes ditransitive verbs syntactically unique. Selection in generative grammar is often modelled as syntactic sisterhood, so ditranstive verbs immediately raise the question of whether a verb might have two sisters, requiring a ternary-branching structure, or whether one of the two internal arguments is not in a sisterhood relation with the verb. Another important property of English ditransitive constructions is the two syntactic structures associated with them. In the so-called “Double Object Construction”, or DOC, the Goal and Theme both are simple NPs and appear following the verb in the order V-Goal-Theme. -

The Special Datives

The Special Datives To this point, the functions of the Dative Case have been 1. Indirect Object of give, tell, show verbs 2. Dative with Special Adjectives friendly to, unfriendly to, similar to, dissimilar to, equal to, suitable for, near to, dear to, pleasing to, etc. 3. Dative with Special Intransitive Verbs parco, mando, impero, noceo, resisto, studeo, etc. 4. Dative with Certain Compound Verbs praesum, praeficio, occurro, etc. (often verbs with prefixes of ob- and prae-) Two new Dative Case functions, sometimes called Special Datives, are explained in Unit XIII. These are the Dative of Purpose and the Dative of Reference. 1. Dative of Purpose. Sometimes, the idea of purpose can be stated in a single noun. In such a case, the Dative Case form of the noun is used. It answers the question, “For what purpose does something exist?” Note how we often ask, “What is that for?” The consul donated money for a reward. Consul pecuniam praemio donavit. Seven common Latin nouns are often used as (for?!) the Dative of Purpose: Principal Parts Dative Singular Form Meaning cura, -ae, f. curae for a concern auxilium, -I, n. auxilio for a help impedimentum, -I, n. impedimento for an obstacle praemium, -I, n. praemio for a reward praesidium, -I, n. praesidio for a guard subsidium, -I, n. subsidio for a support usus,, -us, m. usui for a use NOTA BENE: These are not the only nouns which may be used for purpose; they are only the most common. Sometimes a plural Dative Case form is used for purpose. Catullus poeta scripsit puellas esse curis. -

The Old English To-Dative Construction1 Ghent

1 The Old English to-dative construction1 LUDOVIC DE CUYPERE Ghent University 1 Acknowledgements: I wish to acknowledge helpful comments and suggestions by Cynthia Allen and Harold Koch. I am grateful to Daan Van den Nest for assisting me with the retrieval of the corpus data I also thank Joan Bresnan for providing me with an R script to perform the cross- validation test. Finally, I am grateful to the editor and the referees for several comments and suggestions that helped to improve the paper. 2 Abstract In Present Day English (PDE), the to-dative construction refers to clauses like John told/offered/mentioned/gave the books to Mary, in which a ditransitive verb takes a Recipient that is expressed as a to-Prepositional Phrase (to-PP). This study examines the to-dative construction in Old English (OE). I show, first of all, that this construction was not rare in OE, in contrast to what has been suggested in the literature. Second, I report on two corpus studies in which I examined the ordering behaviour of the NP and the to-PP. The results of the first study suggest that the same ordering tendencies already existed in OE as in PDE: both the NP-to-PP and the to- PP-NP orders were grammatical, but the NP-to-PP was the most frequently used one. However, in OE, the to-PP-NP was more common than in PDE, where its use is heavily restricted. My second corpus study is informed by the multifactorial approach to the English dative alternation and uses a mixed-effects logistic regression analysis to evaluate the effects of various linguistic (verbal semantics, pronominality, animacy, definiteness, number, person and length) and extra- linguistic variables (translation status, time of completion/manuscript) on the ordering of NP and to-PP. -

First Objects and Datives: Two of a Kind?

BLS 32 February 2006 First Objects and Datives: Two of a Kind? Beth Levin Stanford University ([email protected]) 1 The big question There are two options for expressing recipients in English with dative verbs—verbs taking agent, recipient, and theme arguments, such as give and other verbs of causation of possession. (1) a. Terry gave Sam an apple. (double object construction) b. Terry gave an apple to Sam. (to construction) Many languages which lack a double object construction still have a core (i.e., nonadjunct) grammatical relation, distinct from subject and object, used to express recipient. Specifically, many languages have a dative case and use the dative (case marked) NP as the basic realization of possessors, including recipients of verbs of causation of possession. (2) Ja dal Ivanu knigu. I.NOM give.PST Ivan.DAT book.ACC ‘I gave Ivan a book.’ (RUSSIAN; dative construction) A PERENNIAL QUESTION: What is the status of the first object in the double object construction? — Is it comparable to the object of a transitive verb? AN ANSWER: YES is implicit in the label “first/primary/inner object” and is supported by its passivizability and postverbal position; cf. Dryer’s (1986) “primary object languages”. (3) Sam was given an apple. — Is it comparable to the dative NP of languages with a dative case? AN ANSWER: In the context of the answer to the previous question, NO is the usual answer given; it is the NP in the to phrase in the to construction that is equated with the dative NP. THE COMPLICATION: Repeated observations that despite surface similarities with direct objects, recipients in the double object construction do not show all direct object properties (e.g., Baker 1997; Hudson 1992; Maling 2001; Marantz 1993; Polinsky 1996; Ziv & Sheintuch 1979). -

Title Serial Verb Construction in Cantonese-Speaking

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Serial verb construction in Cantonese-speaking preschool Title children with and without language impairment Author(s) Chan, Ka-yee; 陳嘉儀 Chan, K. [陳嘉儀]. (2014). Serial verb construction in Cantonese- speaking preschool children with and without language Citation impairment. (Thesis). University of Hong Kong, Pokfulam, Hong Kong SAR. Issued Date 2014 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/238921 The author retains all proprietary rights, (such as patent rights) and the right to use in future works.; This work is licensed under Rights a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTION IN CANTONESE PRESCHOOLER 1 Serial Verb Construction in Cantonese-Speaking Preschool Children With and Without Language Impairment CHAN Ka Yee A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Science (Speech and Hearing Sciences), The University of Hong Kong, June 30, 2014. SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTION IN CANTONESE PRESCHOOLER 2 List of Abbreviations CL Noun Classifier LP Linking Particle PERT Perfective Aspect Marker V-PRT Verbal Particle SERIAL VERB CONSTRUCTION IN CANTONESE PRESCHOOLER 3 Serial Verb Construction in Cantonese-Speaking Preschool Children With and Without Language Impairment CHAN Ka Yee Abstract Serial verb construction (SVC) is very productive in Cantonese and it develops actively in the preschool years. Little is known about the development of SVC of children with language impairment (LI). Forty-four kindergarten children with and without LI, aged between 4 to 6 years, participated in the study. This study made use of a video description task to examine the developmental and error patterns of five subtypes of SVC, which were directional, instrumental, benefactive, purpose and dative SVC. -

Plural Addressee Marker and Grammaticalization in Barayin

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by SOAS Research Online Published as: Lovestrand, Joseph. 2018. Plural addressee marker and Pre-publication version grammaticalization in Barayin. Journal of Afroasiatic Languages and Linguistics 10(1) https://doi.org/10.1163/18776930-01001004 Accepted version downloaded from SOAS Research Online: http:// eprints.soas.ac.uk/32651 Plural addressee marker and grammaticalization in Barayin Joseph Lovestrand, University of Oxford Abstract This article describes two distinct but related grammaticalization paths in Barayin, an East Chadic lan- guage. One path is from a first-person plural pronoun to a first-person dual pronoun. Synchronically, the pronominal forms in Barayin with first-person dual number must now be combined with a plural addressee enclitic, nà, to create a first-person plural pronoun. This path is identical to what has been documented in Philippine-type languages. The other path is from a first-person dative suffix to a suffix dedicated to first-person hortative. This path of grammaticalization has not been discussed in the literature. It occurred in several related languages, and each in case results in a hortative form with a dual subject. Hortative forms with a plural subject are created by adding a plural addressee marker to the dual form. The plural addressee marker in Chadic languages is derived from a second-person pronominal. Keywords Chadic, Barayin, hortative, dual, pronouns, diachronic1 1 Introduction This paper describes two distinct but related grammaticalization paths in Barayin [bva] and other lan- guages of the Guera subbranch of East Chadic languages (East Chadic B).