Theodore Patrick Abraham Sweeting Columbia 1968

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

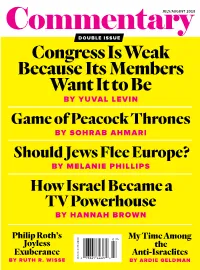

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Vita for Alan M. Wald

1 July 2016 VITA FOR ALAN M. WALD Emeritus Faculty as of June 2014 FORMERLY H. CHANDLER DAVIS COLLEGIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND AMERICAN CULTURE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR Address Office: Prof. Alan Wald, English Department, University of Michigan, 3187 Angell Hall, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48109-1003. Home: 3633 Bradford Square Drive, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48103 Faxes can be received at 734-763-3128. E-mail: [email protected] Education B.A. Antioch College, 1969 (Literature) M.A. University of California at Berkeley, 1971 (English) Ph. D. University of California at Berkeley, 1974 (English) Occupational History Lecturer in English, San Jose State University, Fall 1974 Associate in English, University of California at Berkeley, Spring 1975 Assistant Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1975-81 Associate Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1981-86 Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1986- Director, Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, 2000-2003 H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor, University of Michigan, 2007-2014 Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan, 2014- Research and Teaching Specialties 20th Century United States Literature Realism, Naturalism, Modernism in Mid-20th Century U.S. Literature Literary Radicalism in the United States Marxism and U.S. Cultural Studies African American Writers on the Left Modernist Poetry and the Left The Thirties New York Jewish Writers and Intellectuals Twentieth Century History of Socialist, Communist, Trotskyist and New Left Movements in the U.S. -

Jews and the New York Intellectuals

in her apartment. She was a genius at teasing Wisse: I want to read from a lecture that out of these files of the back issues of the For- Leo Strauss delivered in 1962 — republished ward items that illuminated the ironies that as an essay called “Why We Remain Jews.” He we’re speaking of. We lost, when she died, the writes, “The Jewish people and their fate are genius that she put into that column of items living witness for the absence of redemption. from back issues of the Forward. What Jews This, one could say, is the meaning of the cho- sometimes attribute to the neoconservatives sen people; the Jews are chosen to prove the today, are ideas not far off from what were absence of redemption.” It’s a chilling but mainstream liberal views of an earlier time. It’s amazingly incisive way of formulating the like what Ronald Reagan said, “I didn’t leave issue. People who want to believe that the the Democratic Party, it left me.” Lucy under- world has been redeemed or is immediately stood that much of the hostility was hostility redemptive, would have to wish the Jews out to Jews and to the Jewish struggle. I think of of existence since the aggression against them that often these days. so clearly contradicts this faith. Jews and the New York Intellectuals Michael Kimmage he relationship between Jews and neo- munism, socialism, radicalism, conservatism, Tconservatism, neither causal nor compre- and his own cherished liberalism. hensive, grows more organic when focused on Finally, the New York intellectual milieu the New York intellectuals, a class of writers encouraged debate about politics that was ori- and critics that came of age in the 1930s and ented toward the public sphere and resistant into maturity after World War II. -

Power, Dissent, and the Contest of Intellectual Virtues in the 1950S

The Anxiety of Irrelevance: Power, Dissent, and the Contest of Intellectual Virtues in the 1950s Allon Brann Senior Thesis April 2010 Advisor: Professor William Leach Second Reader: Professor Casey Blake 1 Acknowledgments If there is one thing about this essay that most satisfies me, it is that the process of writing it felt like a fitting conclusion to my undergraduate career. In conceiving of my project, I wanted to draw out the issues that most challenged me over four years of study, and to try to interrogate them, side by side, one last time. I want to say at the outset, then, that I believe each one of my extraordinary teachers at Columbia has contributed to this project. There has been no greater intellectual pleasure over the last four years than discovering unforeseen connections between the different texts and problems that I had the opportunity to investigate with each of them. There are, of course, a few whom I must identify here individually. Professor William Leach guided our seminar with great patience and taught me much about good historical writing. In addition to serving as my second reader for this essay, Professor Casey Blake laid the groundwork for my exploration of American intellectual history. He introduced me to many of the figures who have most inspired—and at times, troubled—me in my study of the past, and with whom I hope to continue to engage long after the completion of this project. I am grateful, as well, to Professor Ross Posnock, whose course pushed me to question the role of the thinker in American society, past and present. -

SDS's Failure to Realign the Largest Political Coalition in the 20Th Century

NEW DEAL TO NEW MAJORITY: SDS’S FAILURE TO REALIGN THE LARGEST POLITICAL COALITION IN THE 20TH CENTURY Michael T. Hale A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 2015 Committee: Clayton Rosati, Advisor Francisco Cabanillas Graduate Faculty Representative Ellen Berry Oliver Boyd-Barret Bill Mullen ii ABSTRACT Clayton Rosati, Advisor Many historical accounts of the failure of the New Left and the ascendency of the New Right blame either the former’s militancy and violence for its lack of success—particularly after 1968—or the latter’s natural majority among essentially conservative American voters. Additionally, most scholarship on the 1960s fails to see the New Right as a social movement. In the struggles over how we understand the 1960s, this narrative, and the memoirs of New Leftists which continue that framework, miss a much more important intellectual and cultural legacy that helps explain the movement’s internal weakness. Rather than blame “evil militants” or a fixed conservative climate that encircled the New Left with both sanctioned and unsanctioned violence and brutality––like the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) counter intelligence program COINTELPRO that provide the conditions for a unstoppable tidal wave “with the election of Richard M. Nixon in 1968 and reached its crescendo in the Moral Majority, the New Right, the Reagan administration, and neo-conservatism” (Breines “Whose New Left” 528)––the key to this legacy and its afterlives, I will argue, is the implicit (and explicit) essentialism bound to narratives of the “unwinnability” of especially the white working class. -

"Commentary" in American Life

Introduction Commentary: The First Sixty Years Murray Friedman t was Irving Kristol, Ruth Wisse reminds us, who said that Commentary was one of the most important magazines in Jewish history. This may be an exaggeration, but not by much. Literary critic Richard Pells writes more soberly, I“While other magazines have certainly had their bursts of glory—even Golden Ages—in which one has had to read them to know what was going on in New York, or Washing- ton, or the world—no other journal of the past half century has been so consistently influential, or so central to the major debates that have transformed the political and intel- lectual life of the United States.” The Commentary we are most familiar with today is widely seen as an organ of American political conservatism. Although this is so, from its beginning the magazine had broader scope and purposes, as indeed it continues to have today. Commentary was founded by the American Jewish Committee in 1945 as a monthly journal of “significant thought and opinion, Jewish affairs and contemporary is- sues.” It was modeled on the Partisan Review, a magazine of somewhat similar style and sensibility, although the lat- ter had no formal Jewish institutional ties. A youthful Nor- 1 2 Introduction man Podhoretz once asked Commentary’s first editor, Elliot E. Cohen, what the difference was between the two magazines. Cohen re- sponded that Commentary was a consciously Jewish magazine, but al- though the Partisan Review was Jewish because of its leadership and contributors, it didn’t know it. Although institutionally sponsored, Commentary won complete edi- torial freedom early on—a rare occurrence in organizational life. -

Publications, Encounter, Preuves, and Tempo Presente Soon Established Themselves in Their Respective Markets and Formed the Core of the CCF’S Ongoing Operations

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE DEMISE OF THE CONGRESS FOR CULTURAL FREEDOM: TRANSATLANTIC INTELLECTUAL CONSENSUS AND “VITAL CENTER” LIBERALISM, 1950-1967 Scott Kamen, Master of Arts, 2011 Directed By: Saverio Giovacchini, Associate Professor, Department of History From the 1950 to 1967, the U.S. government, employing the newly formed CIA, covertly provided the majority of the funding for an international organization comprised primarily of Western non-communist left intellectuals known as the Congress for Cultural Freedom. The Paris-based Congress saw its primary mission as facilitating cooperative networks of non-communist left intellectuals in order to sway the intelligentsia of Western Europe away from its lingering fascination with communism. This thesis explores how the Congress largely succeeded in the 1950s in establishing a cohesive international network of intellectuals by fostering a transatlantic consensus around “vital center” liberalism as a necessary guardian of the Western cultural intellectual tradition in the face of perceived communist threats. By examining the ways in which developments in the 1960s shattered this transatlantic consensus this thesis demonstrates how the Congress suffered an inevitable demise as Western intellectuals became disillusioned with American liberalism of the “vital center.” THE DEMISE OF THE CONGRESS FOR CULTURAL FREEDOM: TRANSATLANTIC INTELLECTUAL CONSENSUS AND “VITAL CENTER” LIBERALISM, 1950-1967 By Scott C. Kamen Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2011 Advisory Committee: Professor Saverio Giovacchini, Chair Professor David Freund Professor James Gilbert Professor Mario Del Pero (de facto) © Copyright by Scott C. -

The Literary Criticism of the New York Intellectuals a Defense and Appreciation Eric Glaberson

the literary criticism of the new york intellectuals a defense and appreciation eric glaberson In the flurry of commentary these past few years on the New York Intel lectuals, much of what has been written suggests that while they engaged in criticism of literature, their political concerns essentially subsumed their other interests, that criticism for them was an outlet for extraliterary impulses. Even a book favorable to the group's early critical work, Alan Wald's The New York Intellectuals, finds its ultimate worth residing in their courageously left-wing yet Anti-Stalinist attitudes of the late thirties. However, such responses tend to obscure what was perhaps the most significant intellectual contribution of the New York Intellectuals: their exploration of the emotional resonances brought about through the social and historical dimensions of literature. In this process, they have over most of the last fifty years refused to compromise the integrity of works of literature for political purposes. This essay, then, will argue that the New York Intellectuals' later critical work was largely nonpolitical. It will attempt to demonstrate as well that 1) the dialectical nature of their work helped to illuminate much of the literature of the last two centuries; 2) to a large extent their dialectic grew out of the Jewish immigrant experience, strengthening rather than narrowing their work; 3) they followed in a tradition of American cultural criticism stemming from Van Wyck 71 Brooks and Edmund Wilson; and 4) their emphasis on the historical, cultural and moral elements of literature served a humanizing function in American critical practice. -

“The Intellectual,” Vaclav Havel Has Written

“The intellectual,” Vaclav Havel has written, “should constantly disturb, should bear witness to the misery of the world, should be provocative by being independent, should rebel against all hidden and open pressure and manipulations, should be the chief doubter of systems, of power and its incantations, should be a witness to their mendacity.”1 In this wonderfully eloquent passage, composed in 1986 when the Czechoslovakia’s Communist regime still had the capacity to make life hellish for those who dared to oppose it, Havel provides a particularly vivid expression of the perspective that has dominated most thinking and writing about intellectuals: that they are “disturbers of the peace” whose ultimate responsibility is to tell the truth, even (and perhaps especially) if it arouses the ire of the established authorities. In so arguing, Havel joins a long tradition of discourse about intellectuals beginning with Zola and extending though Benda and Orwell to Kolakowski and many others which insists that the proper function of intellect is, in the memorable words of Ignazio Silone, “the humble and courageous service of truth.”2 That this viewpoint, which we shall call here the “moralist” tradition, retains vitality today is illustrated by no less a figure then Edward Said, who in delivering the prestigious Reith Lectures for the BBC in 1993, repeatedly emphasized that the tasks of the contemporary intellectual is “to speak the truth to power.”3 For the social theorist who wishes to understand the place of intellectuals in politics, the fundamental problem with the moralist tradition exemplified by Havel is that it treats intellectuals not as they actually are, but as they should be. -

The Bohemian Horizon: 21St-Century Little Magazines and the Limits of the Countercultural Artist-Activist

The Bohemian Horizon: 21st-Century Little Magazines and the Limits of the Countercultural Artist-Activist Travis Mushett Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2016 ©2016 Travis Mushett All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Bohemian Horizon: 21st-Century Little Magazines and the Limits of the Countercultural Artist-Activist Travis Mushett This dissertation examines the emergence of a cohort of independent literary, intellectual, and political publications—“little magazines”—in New York City over the past decade. Helmed by web-savvy young editors, these publications have cultivated formidable reputations by grasping and capitalizing on a constellation of economic, political, and technological developments. The little magazines understand themselves as a radical alternative both to a journalistic trend toward facile, easily digestible content and to the perceived insularity and exclusivity of academic discourse. However, the bohemian tradition in which they operate predisposes them toward an insularity of their own. Their particular web of allusions, codes, and prerequisite knowledge can render them esoteric beyond the borders of a specific subculture and, in so doing, curtail their political potency and reproduce systems of privilege. This dissertation explores the tensions and limitations of the bohemian artist-activist ideal, and locates instances in which little magazines were able to successfully