The New York Intellectuals and the Cuban Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

108 Left History 6.1 Edward Alexander, Irving Howe

108 Left History 6.1 Edward Alexander, Irving Howe -Socialist, Critic,Jew (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1998). "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds ..." -Emerson It is interesting to speculate on how Irving Howe, student of Emerson, would have responded to this non-biographic, not-quite-intellectual-historical survey of his career. For it is a study that keeps demanding an impossible consistency from a life ever responding to changing intellectual currents. And the responses come from first a very young, then a middle-aged, and eventually an older, concededly wiser writer. Alexander's title promises four themes, but develops only three. We have socialist, critic, Jew; we don't have the man, Irving Howe. In place of a thesis, Alexander offers strong opinions: praise of Howe for letting the critic in him eventually moderate the socialism and the secular Jewishness, but scorn for his remaining a socialist and for never becoming, albeit Jewish, a practicing Jew. If Howe could have responded at all, it would, of course, have been in a dissent. Yet he might have smiled at Alexander's attempts to come to tenns with one infuriating consistency: Howe's passion for whatever he thought and whatever he did, even when he was veering 180 degrees from a previous passion. Mostly, the book is a seriatim treatment of Howe's writings, from his fiery youthful Trotskyite pieces to his late conservative attacks on joyless literary theorists. Alexander summarizes each essay or book in order of appearance, compares its stance to that of its predecessors or successors, and judges them against an implicit set of unchanging values of his own, roughly identifiable to a reader as the later political and religious positions of Commentary magazine. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

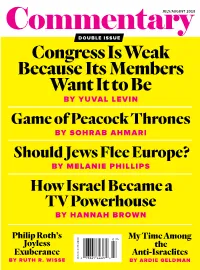

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

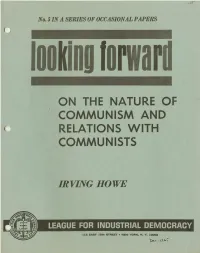

Communism and Relations with Communists

No.5 IN A SERIES OF OCCASIONAL PAPERS ON THE NATURE OF .· COMMUNISM AND RELATIONS WITH COMMUNISTS IRVING HOWE 112 EAST 19th STREET • NEW YORK, N. Y. 10003 ~t:. L)l,) ON THE NA URE OF COMMUNISM AND RE . ONS WITH COMMUNISTS By IRVING HOWE The following article was written for a special purpose. It wa.r comMis.ri.IYC •y tJu League for Industrial Democracy aJ part of a group of writings to be submitted t• a .r~cial c01tj1rence of Stu dents for a .Democratic Society held dur_ing Christmas week 1965. The ~~r i.J .,. eff•rt to explain to younger student radicals the attitude toward Communism held by persons like myself on the democratic left. When the LID proposed to rel.Jrint this paper for wider circulation, I . thought at first of rewriting it, so that there would be no evidence of the special occa.rion for which it was produced. But on second thought, I have left the paper as it was written, so that it will retail its character and, perhaps, interest as a contribution to the discussion between generations. - I. H. I shall attempt something here that may be country has been demagogically exploited for re in1modest and impractical-to suggest, in com actionary ends. pressed form, the views held by persons like my In any case, we would favor various steps to self, those who call themselves democratic social ward the demilitarization of central Europe; to ists, on a topic of enormous complexity. For the wards arrangements with China in behalf of stab immediate purpos·es of provoking a discussion, ility in the Far East; and towards all sorts of these notes may, however, be of some use. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Beyond the First 100 Days Toward a Progressive Agenda

PUBLISHED BY THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISTS OF AMERICA May /June 1993 Volume XXI Number 3 REMEMBERING IRVING HOWE 1920-1993 BEYOND THE FIRST 100 DAYS TOWARD A PROGRESSIVE AGENDA • FIXING THE ECONOMY • FIGI-ITING RACISM • REVITALIZING LABOR INSIDE DEMOCRATIC LEFT Coming to Grips with Clintonomics DSAction . 14 by Mark Levinson ... 3 Remembering Ben Dobbs by Steve Tarzynski. 15 Race In the Clinton Era by Michael Eric Dyson . 7 We Need Labor Law Reform by Jack Sheinkman ... 16 On the Left by Harry Fleischman. 11 Notes On European Integration by Peter Mandler . 19 Irving Howe, 1920 - 1993 Remembrances by Jo-Ann Mort and Janie Higgins Reports ... 24 cover photos: Irving Howe courtesy of Harcourt Brace Jack Clark . 12 Jovanovich; Biii Clinton by Brian Palmer/Impact Visuals. Correction A photo credit was missing from page 15 of the Mark Your Calendar: March/April issue. The -upper photo on that page should have been credited to Meryl Levin/Impact The 1993 DSA Convention Visuals. November 11 • 14 upcoming screenings of the film Los Angeles, California MANUFACTURING CONSENT: NOAM CHOMSKY AND THE MEDIA Join Barbara Ehrenreich, San Diego Ken Theatre May 20-24 Corvallis Oregon Stau June4 Jose Laluz, and Cornel West Sacramento Crest Tlreatre June 9-10 Seattle Neptune June 10-16 Milwaukee Oriental Tlieater June 11-17 more information soon Denver Mayan Tlreatre June 25 - July 1 Chicago Music Box July 3 and 4 CLASSIFIEDS DEMOCRATIC LEFT DEATH ROW INMATE 15 yrs Managing Editor ENCYCLOPEDIA OF THE needs friends, Ron Spivey, Box Michael Lighty AMERICAN LEFT, now in 3877C4104, Jackson, CA 30233 PAPERBACK, 970 pp., doz Production ens of entries on and/or by "A SHORT APPREHENSIVE David Glenn DSAers. -

Rethinking the Historiography of United States Communism: a Comment

American Communist History, Vol. 2, No. 2, 2003 Rethinking the Historiography of United States Communism: A Comment JOHN MCILROY Bryan Palmer’s critical commentary on the historiography of American Com- munism is eloquent and persuasive and I fully endorse the core components of his argument. Absent or insubstantial in many studies, both traditional and revisionist, a singular casualty of historical amnesia, Stalinism matters. A proper understanding of American Communism demands an account of its political refashioning from the mid-1920s.1 Moreover, Palmer’s important rehabilitation of the centrality of programmatic disjuncture opens up what a simplistic dissolution of Stalinism into a timeless, ahistorical official Commu- nism closes down: the existence of and the need to historicize different Commu- nisms, the reality of an “anti-Communism” of the left as well as of the right, the possibility of rediscovering yesterday and tomorrow a revolutionary interna- tionalism liberated from Stalinism which threatened not only capital but organized labor, working-class freedoms and any prospect of socialism. In this note I can touch tersely on only two points: the issue of continuity and rupture in the relationship between the Russians and the American Party in the 1920s and the question of how alternative Communisms handled the problem of international organization. Russian Domination and Political Rupture My emphasis on the continuity of Moscow control of US Communism is different from Palmer’s. What I find striking is the degree to which Russian domination of the Comintern and thus of the politics of its American section was sustained from 1920, even if the political content of that domination changed significantly as Stalinism developed. -

Bio-Bibliographical Sketch of Max Shachtman

The Lubitz' TrotskyanaNet Max Shachtman Bio-Bibliographical Sketch Contents: • Basic biographical data • Biographical sketch • Selective bibliography • Notes on archives Basic biographical data Name: Max Shachtman Other names (by-names, pseud. etc.): Cousin John * Marty Dworkin * M.S. * Max Marsh * Max * Michaels * Pedro * S. * Max Schachtman * Sh * Maks Shakhtman * S-n * Tr * Trent * M.N. Trent Date and place of birth: September 10, 1904, Warsaw (Russia [Poland]) Date and place of death: November 4, 1972, Floral Park, NY (USA) Nationality: Russian, American Occupations, careers, etc.: Editor, writer, party leader Time of activity in Trotskyist movement: 1928 - ca. 1948 Biographical sketch Max Shachtman was a renowned writer, editor, polemicist and agitator who, together with James P. Cannon and Martin Abern, in 1928/29 founded the Trotskyist movement in the United States and for some 12 years func tioned as one of its main leaders and chief theoreticians. He was a close collaborator of Leon Trotsky and translated some of his major works. Nicknamed Trotsky's commissar for foreign affairs, he held key positions in the leading bodies of Trotsky's international movement before, in 1940, he split from the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), founded the Workers Party (WP) and in 1948 definitively dissociated from the Fourth International. Shachtman's name was closely webbed with the theory of bureaucratic collectivism and with what was described as Third Campism ('Neither Washington nor Moscow'). His thought had some lasting influence on a consider able number of contemporaneous intellectuals, writers, and socialist youth, both American and abroad. Once a key figure in the history and struggles of the American and international Trotskyist movement, Shachtman, from the late 1940s to his death in 1972, made a remarkable journey from the left margin of American society to the right, thus having been an inspirer of both Anti-Stalinist Marxists and of neo-conservative hard-liners. -

Pressing Forward the Fight for National Health Care

Inside: A Socialist Night At the Movies PUBLISHED BY THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALISTS OF AMERICA March/ April 1994 E T -·~·= Volume XXII Number 2 Pressing Forward The Fight for National Health Care Susan Cowell on This Year's Congressional Battles Theda Skocpol on the History of Health Care Activism Single Payer Across the Nation: Reports from DSA Locals INSIDE DEMOCRATIC LEFT PRESSING FORWARD: DSAction. .11 THE FIGHT FOR On the Left NATIONAL HEALTH INSURANCE by Harry Fleischman . .. 12 Next Steps for Single-Payer Activists by Susan Cowell . .3 A Socialist Night at the Movies compiled by Mike Randleman. .14 Has the Time Finally Arrived?: Lessons from the History of Health Care Activism Forty Years of Dissent by Theda Skocpol. 6 by Maurice lsserman. .17 Reports from the Field: Jimmy Higgins Reports. .24 DSA Locals' Health Care Work. .10 cover photo: Clark Jonesllmpact Visuals As U.S. progressives, our first But NAFI'A cannot be defeated EDITORIAL impulse may be to make common in the United States alone. It must be cause with the Zapatistas through brought dovm in all three nations. CHIAPAS AND prominent displays of international We have the same :.truggle \\ith the support. For some of our members, same objective. • THE NEW such displays are a fine and noble In DSA's draft Political State expression of socialist values. For ment, we say that " the sociall5t \•alue INTERNATIONALISM others, there is always some discom of international ~olidant} J,) no fort in linking our organization to a longer utopian. but a pres::img neces BY ALAN CHARNEY distant armed movement whose po sity for any democratic reform:. -

Hotel Bristol” Question in the First Moscow Trial of 1936

New Evidence Concerning the “Hotel Bristol” Question in the First Moscow Trial of 1936 Sven-Eric Holmström Leon Sedov Leon Trotsky John Dewey 1. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to introduce new evidence regarding the Hotel Bristol in Copenhagen, the existence of which was questioned after the First Moscow Trial of August, 1936. The issue of Hotel Bristol has perhaps been the most used “evidence” for the fraudulence of the Moscow Trials. This essay examines the Hotel Bristol question as it was dealt with in the Dewey Commission hearings of 1937 in Mexico by carefully examining newly uncovered photographs and primary documents. The essay concludes that • There was a Bristol located where the defendant in question said it was. This Bristol was in more than one way closely connected to a hotel. • Leon Trotsky lied deliberately to the Dewey Commission more than once. • Trotsky’s son Leon Sedov and one of Trotsky’s witnesses also lied. • The examination of the Hotel Bristol question made by the Dewey Commission can at the best be described as sloppy. This means that the credibility of the Dewey Commission must be seriously questioned. Copyright © 2008 by Sven-Eric Holmström and Cultural Logic, ISSN 1097-3087 Sven-Eric Holmström 2 • The author Isaac Deutscher and Trotsky’s secretary, Jean Van Heijenoort, covered up Trotsky’s continuing contact with his supporters in the Soviet Union. • It was probably Deutscher and/or Van Heijenoort who purged the Harvard Trotsky Archives of incriminating evidence, a fact discovered by researchers during the early 1980s. • This is the strongest evidence so far that the testimony in the 1936 Moscow Trial was true, rather than a frame up. -

Music for a Shadow Play)

Gamelan (Music for a Shadow Play) By Lawrence R. Tirino ©2013 To the good people who have been led astray by madmen, and especially to those who have suffered as a result. 1.Death in the Afternoon Chucha de tu madre! Que bestia!¨ Louis grumbled under his breath as he listened to the men on red scooters visiting all the small shopkeepers. ¨Chulqueros! ¨ He spat into the gutter. ¨Todo el pueblo anda chiro; ¨ - meaning of course that everyone‟s pockets held lint, or dust, or assorted garbage, but none of them held any money. They can‟t get credit cards, and banks won‟t lend them the small amounts that they needed to keep their business running, so they look for one of the countless street shysters that sit drinking coffee at beachfront restaurants in the afternoons when the sun has mellowed. These merchant bankers are the survivors who fled the brutality of their own countries; and although they now wear fine leather shoes and silk shits, the scent of decadence still clings to their pores. Last year they were charging twenty per cent of the principle on the first of the month. Nervous shopkeepers were easily confused into believing that they were paying the same rates as banks. Now it was even easier; a few dollars every day. But all the borrower ever pays is interest. One day the victim wakes up and realizes their mistake; and then they fold and disappear into the nighttime air. Or perhaps the back page of the morning paper. Sunday, the saddest day. -

Vita for Alan M. Wald

1 July 2016 VITA FOR ALAN M. WALD Emeritus Faculty as of June 2014 FORMERLY H. CHANDLER DAVIS COLLEGIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND AMERICAN CULTURE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR Address Office: Prof. Alan Wald, English Department, University of Michigan, 3187 Angell Hall, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48109-1003. Home: 3633 Bradford Square Drive, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48103 Faxes can be received at 734-763-3128. E-mail: [email protected] Education B.A. Antioch College, 1969 (Literature) M.A. University of California at Berkeley, 1971 (English) Ph. D. University of California at Berkeley, 1974 (English) Occupational History Lecturer in English, San Jose State University, Fall 1974 Associate in English, University of California at Berkeley, Spring 1975 Assistant Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1975-81 Associate Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1981-86 Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1986- Director, Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, 2000-2003 H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor, University of Michigan, 2007-2014 Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan, 2014- Research and Teaching Specialties 20th Century United States Literature Realism, Naturalism, Modernism in Mid-20th Century U.S. Literature Literary Radicalism in the United States Marxism and U.S. Cultural Studies African American Writers on the Left Modernist Poetry and the Left The Thirties New York Jewish Writers and Intellectuals Twentieth Century History of Socialist, Communist, Trotskyist and New Left Movements in the U.S.