Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BEYOND PUBLIC CHOICE and PUBLIC INTEREST: a STUDY of the LEGISLATIVE PROCESS AS ILLUSTRATED by TAX LEGISLATION in the 1980S

University of Pennsylvania Law Review FOUNDED 1852 Formerly American Law Register VOL. 139 NOVEMBER 1990 No. 1 ARTICLES BEYOND PUBLIC CHOICE AND PUBLIC INTEREST: A STUDY OF THE LEGISLATIVE PROCESS AS ILLUSTRATED BY TAX LEGISLATION IN THE 1980s DANIEL SHAVIRO" TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 3 II. HISTORICAL OVERVIEW OF CYCLICAL TAX LEGISLATION ... 11 A. Legislation From the Beginning of the Income Tax Through the 1970s: The Evolution of Tax Instrumentalism and Tax Reform ..................................... 11 t Assistant Professor, University of Chicago Law School. The author was a Legislation Attorney with theJoint Committee of Taxation during the enactment of the 1986 tax bill discussed in this Article. He is grateful to Walter Blum, Richard Posner, Cass Sunstein, and the participants in a Harvard Law School seminar on Current Research in Taxation, held in Chatham, Massachusetts on August 23-26, 1990, for helpful comments on earlier drafts, to Joanne Fay and Michael Bonarti for research assistance, and to the WalterJ. Blum Faculty Research Fund and the Kirkland & Ellis Faculty Fund for financial support. 2 UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 139: 1 B. The 1981 Act and Its Aftermath ................... 19 C. The 1986 Act ............................... 23 D. Aftermath of the 198.6 Act ......................... 29 E. Summary .................................. 30 III. THE PUBLIC INTEREST THEORY OF LEGISLATION ........ 31 A. The Various Strands of Public Interest Theory .......... 31 1. Public Interest Theory in Economics ............ 31 2. The Pluralist School in Political Science .......... 33 3. Ideological Views of the Public Interest .......... 35 B. Criticisms of PublicInterest Theory .................. 36 1. (Largely Theoretical) Criticisms by Economists ... 36 a. When Everyone "Wins," Everyone May Lose .. -

The Illusory Distinction Between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1992 The Illusory Distinction between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result David A. Strauss Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David A. Strauss, "The Illusory Distinction between Equality of Opportunity and Equality of Result," 34 William and Mary Law Review 171 (1992). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSORY DISTINCTION BETWEEN EQUALITY OF OPPORTUNITY AND EQUALITY OF RESULT DAVID A. STRAUSS* I. INTRODUCTION "Our society should guarantee equality of opportunity, but not equality of result." One hears that refrain or its equivalent with increasing frequency. Usually it is part of a general attack on gov- ernment measures that redistribute wealth, or specifically on af- firmative action, that is, race- and gender-conscious efforts to im- prove the status of minorities and women. The idea appears to be that the government's role is to ensure that everyone starts off from the same point, not that everyone ends up in the same condi- tion. If people have equal opportunities, what they make of those opportunities is their responsibility. If they end up worse off, the government should not intervene to help them.1 In this Article, I challenge the usefulness of the distinction be- tween equality of opportunity and equality of result. -

Speaking “Truth” to Biopower

4.BLOOM.MACRO.12.29.11 (DO NOT DELETE) 1/20/2012 11:46 AM SPEAKING “TRUTH” TO BIOPOWER Anne Bloom* INTRODUCTION Left-leaning plaintiffs‟ lawyers sometimes describe their work as “Speaking Truth to Power.”1 The “Truth” they speak usually involves tales of government or corporate wrongdoing, while the power they confront is usually institutional.2 I am a long-time supporter of the plaintiffs‟ bar and believe that the work that they are doing is important. At the same time, I would like to propose an alternative way of “Speaking Truth to Power” that involves somewhat different understandings of both truth and power. I call this strategy “Speaking „Truth‟ to Biopower.” “Speaking „Truth‟ to Biopower” is a pragmatic strategy for legal activism that incorporates postmodern insights regarding the nature of both “truth” and “power.” “Truth” is in quotes to emphasize its contingency – the impossibility of understanding what truth means outside of a particular political and social context. “Biopower” replaces “Power” to highlight the ways in which the body is a key site of contestation in contemporary political struggles.3 While these insights are postmodern,4 the strategy I propose is not. Instead of rejecting legal arguments that rely upon foundational beliefs or “truths” (as would be characteristic of a postmodern approach),5 I argue it is more useful to strategically deploy legal “truths” in * Professor of Law, the University of the Pacific/McGeorge School of Law. Thanks to Danielle Hart for her efforts in putting together this symposium and for her comments on earlier versions of this essay. -

Polish Women's Employment in Delaware County, 1900-1930

Patterns jor Getting By: Polish Women's Employment in Delaware County, 1900-1930 S IN MUCH OF THE EASTERN UNITED STATES, the industrial working class of Pennsylvania since the mid-nineteenth cen- A tury has largely been an immigrant workforce. Understanding the work experience and household strategies of the peoples who inhabited the mill towns and industrial neighborhoods of the state necessarily involves an awareness of both the background experience in the natal country as well as the process of Americanization. By analyzing household patterns in three industrial neighborhoods of suburban Philadelphia, I have found an intersection between immi- grant status and working-class needs in the work strategies of Polish- born women in the first three decades of this century. Since the early 1970s social scientists have explored the ethnic differences among immigrant peoples in the United States. Part of this effort has been tied to an ongoing debate within the social sciences about the nature of ethnicity. Early writers often defined ethnic iden- tity as the continuation of cultural traits from the immigrant's country of origin in America.1 Their studies set up a dichotomy between the "traditions" of the home culture and pressures for assimilation in the United States. Life in the country of origin was frequently character- ized as having unchanging values regarding family roles. By describing 1 The most prominent social science examples of this view are Nathan Glazer and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Beyond the Melting Pot (Cambridge, 1970), and Glazer and Moynihan, Ethnicity: Theory and Experience (Cambridge, 1975); Andrew Greeley, Ethnicity in the U.S.: A Preliminary Reconnaissance (New York, 1974), and Greeley, Why Can't They be Like Us? America's White Ethnic Groups (New York, 1975); and Michael Novak, The Rise oj the Unmeltable Ethnics (New York, 1971). -

Why Creative Workers' Attitudes May Reinforce Social Inequality

This is a repository copy of ‘Culture is a meritocracy’: Why creative workers’ attitudes may reinforce social inequality. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/121610/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Taylor, M.R. orcid.org/0000-0001-5943-9796 and O'Brien, D. (2017) ‘Culture is a meritocracy’: Why creative workers’ attitudes may reinforce social inequality. Sociological Research Online. ISSN 1360-7804 https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780417726732 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Culture is a meritocracy: Why Abstract The attitudes and values of cultural and creative workers are an important element of explaining current academic interest in inequality and culture. To date, quantitative approaches to this element of cultural and creative inequality has been overlooked, particularly in British research. This paper investigates the attitudes of those working in creative jobs with a unique dataset, a web survey of creative Using principal components analysis and regression, we have three main findings. -

Plutocracy: the Marketising of ‘Equality’ Within Neoliberalism

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Littler, J. (2013). Meritocracy as plutocracy: the marketising of ‘equality’ within neoliberalism. New Formations: a journal of culture/theory/politics, 80-81, pp. 52-72. doi: 10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 This is the published version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/4167/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.3898/NewF.80/81.03.2013 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] MERITOCRACY AS PLUTOCRACY: THE MARKETISING OF ‘EQUALITY’ UNDER NEOLIBERALISM Jo Littler Abstract Meritocracy, in contemporary parlance, refers to the idea that whatever our social position at birth, society ought to facilitate the means for ‘talent’ to ‘rise to the top’. This article argues that the ideology of ‘meritocracy’ has become a key means through which plutocracy is endorsed by stealth within contemporary neoliberal culture. -

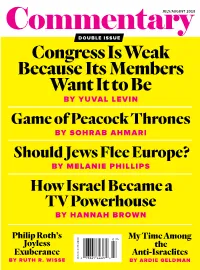

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

Curriculum Vitae (Updated August 1, 2021)

DAVID A. BELL SIDNEY AND RUTH LAPIDUS PROFESSOR IN THE ERA OF NORTH ATLANTIC REVOLUTIONS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY Curriculum Vitae (updated August 1, 2021) Department of History Phone: (609) 258-4159 129 Dickinson Hall [email protected] Princeton University www.davidavrombell.com Princeton, NJ 08544-1017 @DavidAvromBell EMPLOYMENT Princeton University, Director, Shelby Cullom Davis Center for Historical Studies (2020-24). Princeton University, Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the Era of North Atlantic Revolutions, Department of History (2010- ). Associated appointment in the Department of French and Italian. Johns Hopkins University, Dean of Faculty, School of Arts & Sciences (2007-10). Responsibilities included: Oversight of faculty hiring, promotion, and other employment matters; initiatives related to faculty development, and to teaching and research in the humanities and social sciences; chairing a university-wide working group for the Johns Hopkins 2008 Strategic Plan. Johns Hopkins University, Andrew W. Mellon Professor in the Humanities (2005-10). Principal appointment in Department of History, with joint appointment in German and Romance Languages and Literatures. Johns Hopkins University. Professor of History (2000-5). Johns Hopkins University. Associate Professor of History (1996-2000). Yale University. Assistant Professor of History (1991-96). Yale University. Lecturer in History (1990-91). The New Republic (Washington, DC). Magazine reporter (1984-85). VISITING POSITIONS École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales, Visiting Professor (June, 2018) Tokyo University, Visiting Fellow (June, 2017). École Normale Supérieure (Paris), Visiting Professor (March, 2005). David A. Bell, page 1 EDUCATION Princeton University. Ph.D. in History, 1991. Thesis advisor: Prof. Robert Darnton. Thesis title: "Lawyers and Politics in Eighteenth-Century Paris (1700-1790)." Princeton University. -

The Negro Family: the Case for National Action” (1965)

Daniel Patrick Moynihan “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action” (1965) Introduction Two hundred years ago, in 1765, nine assembled colonies first joined together to demand freedom from arbitrary power. For the first century we struggled to hold together the first continental union of democracy in the history of man. One hundred years ago, in 1865, following a terrible test of blood and fire, the compact of union was finally sealed. For a second century we labored to establish a unity of purpose and interest among the many groups which make up the American community. That struggle has often brought pain and violence. It is not yet over. State of the Union Message of President Lyndon B. Johnson, January 4, 1965. The United States is approaching a new crisis in race relations. In the decade that began with the school desegregation decision of the Supreme Court, and ended with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the demand of Negro Americans for full recognition of their civil rights was finally met. The effort, no matter how savage and brutal, of some State and local governments to thwart the exercise of those rights is doomed. The nation will not put up with it — least of all the Negroes. The present moment will pass. In the meantime, a new period is beginning. In this new period the expectations of the Negro Americans will go beyond civil rights. Being Americans, they will now expect that in the near future equal opportunities for them as a group will produce roughly equal results, as compared with other groups. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Menorah Review VCU University Archives

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Menorah Review VCU University Archives 2001 Menorah Review (No. 51, Winter, 2001) Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/menorah Part of the History of Religion Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons © The Author(s) Recommended Citation https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/menorah/50 This Full Issue is brought to you for free and open access by the VCU University Archives at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Menorah Review by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NUMBER 51 • CENTER FOR JUDAIC STUDIES OF VIRGINIA COMMONWEALTH UNIVERSITY • WINTER 2001 For the Enrichment of Jewish Thought But what liftshis volume from the inevitable ethos that permeated and inspired this mi Celebrating Nathan constrictions of its era is an awareness of the nority group could not in any logically satis Glazer's American Judaism unacknowledged tensions, the unaddressed factory way be reconciled with Judaism. problems that were also integral to the com The difference could not be split. munal condition. One dilemma could be In suggesting the depth of the ideologi by Stephen Whitfield said to dwarf-and perhaps even to deter cal problem Jews would have to face, Mr. mine-all the others. He stated it in 1957 Glazer was not writing as a theologian, and The achievement of Nathan Glazer with lapidary power: "There comes a time not quite as a prophet, but as an historian looms large when his American Judaism is and it is just about upon us-when Ameri though he was not formally trained as one. -

A Critical Discussion of Daniel A. Bell's Political Meritocracy

Journal of chinese humanities 4 (2�18) 6-28 brill.com/joch A Critical Discussion of Daniel A. Bell’s Political Meritocracy Huang Yushun 黃玉順 Professor of philosophy, Shandong University, China [email protected] Translated by Kathryn Henderson Abstract “Meritocracy” is among the political phenomena and political orientations found in modern Western democratic systems. Daniel A. Bell, however, imposes it on ancient Confucianism and contemporary China and refers to it in Chinese using loaded terms such as xianneng zhengzhi 賢能政治 and shangxian zhi 尚賢制. Bell’s “politi- cal meritocracy” not only consists of an anti-democratic political program but also is full of logical contradictions: at times, it is the antithesis of democracy, and, at other times, it is a supplement to democracy; sometimes it resolutely rejects democracy, and sometimes it desperately needs democratic mechanisms as the ultimate guar- antee of its legitimacy. Bell’s criticism of democracy consists of untenable platitudes, and his defense of “political meritocracy” comprises a series of specious arguments. Ultimately, the main issue with “political meritocracy” is its blatant negation of popu- lar sovereignty as well as the fact that it inherently represents a road leading directly to totalitarianism. Keywords Democracy – meritocracy – political meritocracy – totalitarianism It is rather surprising that, in recent years, Daniel A. Bell’s views on “political meritocracy” have been selling well in China. In addition, the Chinese edi- tion of his most recent and representative work, The China Model: Political © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi:10.1163/23521341-12340055Downloaded from Brill.com09/23/2021 12:26:47PM via free access A Critical Discussion of Daniel A.