Publications, Encounter, Preuves, and Tempo Presente Soon Established Themselves in Their Respective Markets and Formed the Core of the CCF’S Ongoing Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Non-Communist European Left, 1950-1967

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Honors Theses Lee Honors College 5-2008 Competing Visions: The CIA, the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Non-Communist European Left, 1950-1967 Scott Kamen Western Michigan University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Kamen, Scott, "Competing Visions: The CIA, the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Non-Communist European Left, 1950-1967" (2008). Honors Theses. 912. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/honors_theses/912 This Honors Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Lee Honors College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Competing Visions: The CIA, the Congress for Cultural Freedom and the Non-Communist European Left, 1950-1967 Scott Kamen College of Arts and Science Department of History Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, MI Thesis Committee Edwin Martini, PhD Chair Luigi Andrea Berto, PhD Reader Fred Dobney, PhD Reader Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Senior Thesis and Honors Thesis May 2008 During the tense early years of the Cold War, the United States government, utilizing the newly formed Central Intelligence Agency, covertly provided the majority of the funding for an international organization comprised primarily of non-communistleft (NCL) intellectuals known as the Congressfor Cultural Freedom (CCF). The CCF based their primary mission around facilitating cooperativenetworks of NCLintellectuals and sought to draw upon the cultural influence of these individuals to sway the intelligentsia of Western Europe away from its lingering fascinations with communism and its sympathetic views of the Soviet Union. -

Shock Therapy: the United States Anti-Communist Psychological Campaign in Fourth Republic France

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 Shock Therapy: The United States Anti- Communist Psychological Campaign in Fourth Republic France Susan M. Perlman Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES SHOCK THERAPY: THE UNITED STATES ANTI-COMMUNIST PSYCHOLOGICAL CAMPAIGN IN FOURTH REPUBLIC FRANCE By SUSAN M. PERLMAN A Thesis submitted to the Department of International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the thesis of Susan M. Perlman, defended on February 10, 2006. ______________________________ Max Paul Friedman Professor Directing Thesis ______________________________ Lee Metcalf Committee Member ______________________________ Michael Creswell Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my husband Todd, without whose love and support this would not have been possible, and for my parents Jim and Sandy McCall, who always encouraged me to go the extra mile. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Professor Max Paul Friedman for agreeing to supervise this thesis. Dr. Friedman inspired me to write about U.S. foreign policy and provided me with the encouragement and guidance I needed to undertake and complete this endeavor. Moreover, he has been a true mentor, and has made my time at Florida State the most rewarding of my academic life. In addition, I would like to thank Professor Michael Creswell, who graciously agreed to preview portions of this text on numerous occasions. -

Brsq ##125-126

THE BERTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Double Issue Numbers 125-126 / February-May 2005 l}liRTRAND RUSSELL AND THE COLD WAR Published by The Bertrand Russell Society with the Suiiport of Lehman College -City University of New York Tin BERTRAND Rl/SSTELL SoCIETy Ql/ARTERLy is the official organ of the THE BERTRAND RUSSELL SOCIETY QUARTERLY Bcrtrand Russell Society. Tt publishes Society News and Proceedings, and articles on the history of analytic philosophy, especially those pertaining to Double Issue Russell's life and works, including historical materials and reviews of Numbers 125-126 / February-May 2005 rcccnt work on Russell. Scholarly articles appearing in the ga/czrfcr/); are riccr-rcviewed. EDITORS: Rosalind Carey and John Ongley. BERTRAND RUSSELL AND THE COLD WAR ASSoCIA'rE EDITOR: Ray Perkins Jr. EDiTORIAL AsslsTANT: Cony Hotnit EDITORIAL BOARD CONTENTS Rosalind Carey, Lehman College-CUNY John Ongley, Edinboro University of PA Raymond Perkins, Jr. , Plymouth State University In This Issue Christopher Pincock, Purdue University Society News David Hyder, University of Ottawa Anat Biletzki, Tel Aviv Univer`sity Feature SuL}MlssloNS: All communications to the BerfrczHc7 jiwssc// Sot.i.cty £Ji/c/r/cJr/y, including manuscripts, book reviews, letters to the editor, etc., Bertrand Russell as Cold War Propagandist t`hould be sent to: Rosalind Carey, Philosophy Department, Lehman AN[)REW BONE (Tollcgc-CUNY, 250 Bed ford Park Blvd. West, Bronx, NY 10468, USA, or by email to: [email protected]. Review Essay Sl)l}sl`RlpTloNS: The BRS gwczr/er/y is free to members of the BertTand Rii*scll Society. Society membership is $35 a year for individuals, $40 for Russell studies in Germany Today. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

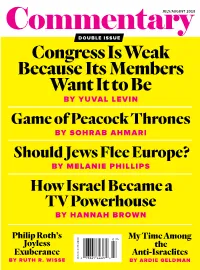

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

'Krym Nash': an Analysis of Modern Russian Deception Warfare

‘Krym Nash’: An Analysis of Modern Russian Deception Warfare ‘De Krim is van ons’ Een analyse van hedendaagse Russische wijze van oorlogvoeren – inmenging door misleiding (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. H.R.B.M. Kummeling, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op woensdag 16 december 2020 des middags te 12.45 uur door Albert Johan Hendrik Bouwmeester geboren op 25 mei 1962 te Enschede Promotoren: Prof. dr. B.G.J. de Graaff Prof. dr. P.A.L. Ducheine Dit proefschrift werd mede mogelijk gemaakt met financiële steun van het ministerie van Defensie. ii Table of contents Table of contents .................................................................................................. iii List of abbreviations ............................................................................................ vii Abbreviations and Acronyms ........................................................................................................................... vii Country codes .................................................................................................................................................... ix American State Codes ....................................................................................................................................... ix List of figures ...................................................................................................... -

“I Am Afraid Americans Cannot Understand” the Congress for Cultural Freedom in France and Italy, 1950–1957

“I Am Afraid Americans Cannot Understand” The Congress for Cultural Freedom in France and Italy, 1950–1957 ✣ Andrea Scionti Culture was a crucial yet elusive battlefield of the Cold War. Both superpowers tried to promote their way of life and values to the world but had to do so care- fully. The means adopted by the United States included not only propaganda and the use of mass media such as cinema and television but also efforts to help shape the world of highbrow culture and the arts. The Congress for Cultural Freedom (CCF), an organization sponsored by the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), offered U.S. policymakers and intellectuals the opportunity to provide indirect support for anti-Communist intellectuals without being openly associated with their activities. Although the CCF represented one of the main instruments for the United States to try to win the hearts and minds of postwar Europe, it also created new challenges for U.S. Cold War- riors. By tying themselves to the European intelligentsia, they were forced to mediate between different societies, cultures, and intellectual traditions. This article looks at the contexts of France and Italy to highlight this interplay of competing notions of anti-Communism and cultural freedom and how the local actors involved helped redefine the character and limits of U.S. cultural diplomacy. Although scholars have looked at the CCF and its significance, es- pecially in the Anglo-Saxon world, a focus on French and Italian intellectuals can offer fresh insights into this subject. The Congress for Cultural Freedom was the product of a convergence of interests between the CIA’s recently established Office of Policy Coordination (OPC) and a small number of American and European intellectuals, many of them former Communists, concerned about the perceived success of the Soviet cultural offensive in Western Europe. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Transatlantica Review.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Norman, Will (2016) The Cultural Cold War. Review of: The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters (2nd edition); and American Literature and Culture in the Age of Cold War by Stonor Saunders, Frances and Belletto, Steven and Grausam, Daniel. Transatlantica: revue d'etudes americaines . N/A. DOI Link to record in KAR http://kar.kent.ac.uk/55620/ Document Version Publisher pdf Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Transatlantica 1 (2015) The Voting Rights Act at 50 / Hidden in Plain Sight: Deep Time and American Literature ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

The Cultural Cold War the CIA and the World of Arts and Letters

The Cultural Cold War The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters FRANCES STONOR SAUNDERS by Frances Stonor Saunders Originally published in the United Kingdom under the title Who Paid the Piper? by Granta Publications, 1999 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2000 Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press oper- ates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in in- novative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450 West 41st Street, 6th floor. New York, NY 10036 www.thenewpres.com Printed in the United States of America ‘What fate or fortune led Thee down into this place, ere thy last day? Who is it that thy steps hath piloted?’ ‘Above there in the clear world on my way,’ I answered him, ‘lost in a vale of gloom, Before my age was full, I went astray.’ Dante’s Inferno, Canto XV I know that’s a secret, for it’s whispered everywhere. William Congreve, Love for Love Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................... v Introduction ....................................................................1 1 Exquisite Corpse ...........................................................5 2 Destiny’s Elect .............................................................20 3 Marxists at -

The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA, and the Arabic Literary Journal "Ḥiwār" (1962-67) Author(S): Elizabeth M

"Bread or Freedom": The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA, and the Arabic Literary Journal "Ḥiwār" (1962-67) Author(s): Elizabeth M. Holt Source: Journal of Arabic Literature, Vol. 44, No. 1, Arabic Literature, Criticism and Intellectual Thought from the "Nahḍah" to the Present, Part II (2013), pp. 83-102 Published by: Brill Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43304750 Accessed: 23-10-2019 01:59 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms Brill is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Arabic Literature This content downloaded from 146.245.216.16 on Wed, 23 Oct 2019 01:59:11 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Journal of Arabie Literature 44 (2013) 83-102 "Bread or Freedom": The Congress for Cultural Freedom, the CIA, and the Arabic Literary Journal Hiwãr (1962-67) Elizabeth M. Holt Bard College Abstract In 1950, the United States Central Intelligence Agency created the Congress for Cultural Free- dom, with its main offices in Paris, lhe CCF was designed as a cultural front in the Cold War in response to the Soviet Cominform, and founded and funded a worldwide network of literary journals (as well as conferences, concerts, art exhibits and other cultural events). -

Vita for Alan M. Wald

1 July 2016 VITA FOR ALAN M. WALD Emeritus Faculty as of June 2014 FORMERLY H. CHANDLER DAVIS COLLEGIATE PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND AMERICAN CULTURE UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR Address Office: Prof. Alan Wald, English Department, University of Michigan, 3187 Angell Hall, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48109-1003. Home: 3633 Bradford Square Drive, Ann Arbor, Mi. 48103 Faxes can be received at 734-763-3128. E-mail: [email protected] Education B.A. Antioch College, 1969 (Literature) M.A. University of California at Berkeley, 1971 (English) Ph. D. University of California at Berkeley, 1974 (English) Occupational History Lecturer in English, San Jose State University, Fall 1974 Associate in English, University of California at Berkeley, Spring 1975 Assistant Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1975-81 Associate Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1981-86 Professor in the English Department and in the Program in American Culture at the University of Michigan, 1986- Director, Program in American Culture, University of Michigan, 2000-2003 H. Chandler Davis Collegiate Professor, University of Michigan, 2007-2014 Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan, 2014- Research and Teaching Specialties 20th Century United States Literature Realism, Naturalism, Modernism in Mid-20th Century U.S. Literature Literary Radicalism in the United States Marxism and U.S. Cultural Studies African American Writers on the Left Modernist Poetry and the Left The Thirties New York Jewish Writers and Intellectuals Twentieth Century History of Socialist, Communist, Trotskyist and New Left Movements in the U.S.