Power, Dissent, and the Contest of Intellectual Virtues in the 1950S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Humble Protest a Literary Generation's Quest for The

A HUMBLE PROTEST A LITERARY GENERATION’S QUEST FOR THE HEROIC SELF, 1917 – 1930 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jason A. Powell, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Steven Conn, Adviser Professor Paula Baker Professor David Steigerwald _____________________ Adviser Professor George Cotkin History Graduate Program Copyright by Jason Powell 2008 ABSTRACT Through the life and works of novelist John Dos Passos this project reexamines the inter-war cultural phenomenon that we call the Lost Generation. The Great War had destroyed traditional models of heroism for twenties intellectuals such as Ernest Hemingway, Edmund Wilson, Malcolm Cowley, E. E. Cummings, Hart Crane, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and John Dos Passos, compelling them to create a new understanding of what I call the “heroic self.” Through a modernist, experience based, epistemology these writers deemed that the relationship between the heroic individual and the world consisted of a dialectical tension between irony and romance. The ironic interpretation, the view that the world is an antagonistic force out to suppress individual vitality, drove these intellectuals to adopt the Freudian conception of heroism as a revolt against social oppression. The Lost Generation rebelled against these pernicious forces which they believed existed in the forms of militarism, patriotism, progressivism, and absolutism. The -

Ralph Ellison and the American Pursuit of Humanism by Richard

Ralph Ellison and the American Pursuit of Humanism by Richard Errol Purcell BA, Rutgers University, 1996 MA, University of Pittsburgh, 1999 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH Faculty of Arts and Sciences This dissertation was presented by Richard Errol Purcell It was defended on May 14th, 2008 and approved by Ronald Judy, Professor, English Marcia Landy, Professor, English Jonathan Arac, Professor, English Dennis Looney, Professor, French and Italian Dissertation Advisor: Paul Bove, Professor, English ii Copyright © by Richard Errol Purcell 2008 iii Ralph Ellison and the American Pursuit of Humanism Richard Purcell, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 In the middle of a 1945 review of Bucklin Moon’s Primer for White Folks, Ralph Ellison proclaims that the time is right in the United States for a “new American humanism.” Through exhaustive research in Ralph Ellison’s Papers at the Library of Congress, I contextualize Ellison’s grand proclamation within post-World War II American debates over literary criticism, Modernism, sociological method, and finally United States political and cultural history. I see Ellison's “American humanism” as a revitalization of the Latin notion of litterae humaniores that draws heavily on Gilded Age American literature and philosophy. For Ellison, American artists and intellectuals of that period were grappling with the country’s primary quandary after the Civil War: an inability to reconcile America’s progressive vision of humanism with the legacy left by chattel slavery and anti-black racism. -

Literary Scholars Association Critics

The 14th Annual Conference of The Association of October 24-26, 2008 Literary Scholars Sheraton Society Hill Hotel Critics and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Literature Titles from Oxford Journals www.adaptation.oxfordjournals.org www.camqtly.oxfordjournals.org www.english.oxfordjournals.org www.alh.oxfordjournals.org www.cww.oxfordjournals.org ADAPTATION AMERICAN LITERARY THE CAMBRIDGE CONTEMPORARY ENGLISH Adaptation provides an HISTORY QUARTERLY WOMEN’S WRITING Published on behalf of international forum to Covering the study of US The Cambridge Quarterly CWW assesses writing The English Association, theorise and interrogate the literature from its origins was established on the by women authors from English contains essays phenomenon of literature through to the present, principle that literature is an 1970 to the present. It on major works of English on screen from both a American Literary History art, and that the purpose of reflects retrospectively on literature or on topics of literary and film studies provides a much-needed art is to give pleasure and developments throughout general literary interest, perspective. forum for the various, enlightenment. It devotes the period, to survey the aimed at readers within often competing voices itself to literary criticism variety of contemporary universities and colleges of contemporary literary and its fundamental aim work, and to anticipate and presented in a lively inquiry. is to take a critical look at the new and provocative and engaging style. accepted views. women’s writing. www.fmls.oxfordjournals.org -

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science *

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science * George REISCH Received: 31.5.2012 Final version: 30.7.2012 BIBLID [0495-4548 (2012) 27: 75; pp. 323-342] ABSTRACT: Historian Richard Hofstadter’s observations about American cold-war politics are used to contextualize Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and argue that substantive claims about the nature of sci- entific knowledge and scientific change found in Structure were adopted from this cold-war political cul- ture. Keywords: Thomas S. Kuhn; The Structure of Scientific Revolutions ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics;” Cold War; James B. Conant; Brainwashing. RESUMEN: Las observaciones del historiador Richard Hofstadter sobre la política americana en la Guerra Fría se uti- lizan para contextualizar La estructura de las revoluciones científicas de Thomas Kuhn y sostener que algunas afirmaciones fundamentales sobre la naturaleza del conocimiento científico y el cambio científico que se pueden hallar en La estructura fueron adoptadas de esta cultura política de la Guerra Fría. Palabras clave: Thomas S. Kuhn; La estructura de las revoluciones científicas ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”; Guerra Fría; James B. Conant; lavado de cerebro. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant. –Richard Hofstadter (1964, 4) 1. Introduction The conventional wisdom holds that Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions of- fered a revolutionary critique of existing scholarship about science. The book swept aside misconceptions wrought by three kinds of intellectuals—logic-chopping philos- ophers who confused their logical models and formulas with historical fact, Whiggish historians who viewed science’s past through the lenses of the present, and text-book writers whose brief, potted historical introductions obscured science’s dynamic, revo- lutionary history. -

108 Left History 6.1 Edward Alexander, Irving Howe

108 Left History 6.1 Edward Alexander, Irving Howe -Socialist, Critic,Jew (Bloomington: Indiana University Press 1998). "A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds ..." -Emerson It is interesting to speculate on how Irving Howe, student of Emerson, would have responded to this non-biographic, not-quite-intellectual-historical survey of his career. For it is a study that keeps demanding an impossible consistency from a life ever responding to changing intellectual currents. And the responses come from first a very young, then a middle-aged, and eventually an older, concededly wiser writer. Alexander's title promises four themes, but develops only three. We have socialist, critic, Jew; we don't have the man, Irving Howe. In place of a thesis, Alexander offers strong opinions: praise of Howe for letting the critic in him eventually moderate the socialism and the secular Jewishness, but scorn for his remaining a socialist and for never becoming, albeit Jewish, a practicing Jew. If Howe could have responded at all, it would, of course, have been in a dissent. Yet he might have smiled at Alexander's attempts to come to tenns with one infuriating consistency: Howe's passion for whatever he thought and whatever he did, even when he was veering 180 degrees from a previous passion. Mostly, the book is a seriatim treatment of Howe's writings, from his fiery youthful Trotskyite pieces to his late conservative attacks on joyless literary theorists. Alexander summarizes each essay or book in order of appearance, compares its stance to that of its predecessors or successors, and judges them against an implicit set of unchanging values of his own, roughly identifiable to a reader as the later political and religious positions of Commentary magazine. -

A Measure of Detachment: Richard Hofstadter and the Progressive Historians

A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT: RICHARD HOFSTADTER AND THE PROGRESSIVE HISTORIANS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS By Wiliiam McGeehan May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Harvey Neptune, Department of History Andrew Isenberg, Department of History ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Richard Hofstadter's innovations in historical method arose as a critical response to the Progressive historians, particularly to Charles Beard. Hofstadter's first two books were demonstrations of the inadequacy of Progressive methodology, while his third book (the Age of Reform) showed the potential of his new way of writing history. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................i CHAPTER 1. A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT..........................................................................1 2. SOCIAL DARWINISM IN AMERICAN THOUGHT………………………………………………26 3. THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION…………………………………………………………..52 4. THE AGE OF REFORM…………………………………………………………………………………….100 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………139 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..144 CHAPTER ONE A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT Great thinkers often spend their early years in rebellion against the teachers from whom they have learned the most. Freud would say they live out a form of the Oedipal archetype, that son must murder his father at least a little bit if he is ever to become his own man. -

In the Decade Immediately Following the Second World War, Many Of

‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought A thesis presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts Julian Tzara Nemeth August 2007 2 This thesis titled ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought by JULIAN TZARA NEMETH has been approved for the Department of History and the College of Arts and Sciences by Kevin Mattson Professor of History Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 Abstract NEMETH, JULIAN TZARA., M.A, August 2007, History ‘A Central Issue of Our Time’: Academic Freedom in Postwar American Thought (108 pp.) Director of Thesis: Kevin Mattson In the early years of the Cold War, more than one hundred American academics lost their jobs because university administrators suspected them of Communist Party membership. How did intellectuals respond to this crisis? Referring to contemporary books, articles, organizational statements, and correspondence, I argue that disputes over academic freedom helped shatter a tenuous liberal consensus, unite conservatives, and challenge defenses of professorial liberty among academia’s largest professional organization, the American Association of University Professors. Specifically, I show how Sidney Hook and Arthur Schlesinger Jr.’s dispute over academic freedom was representative of larger quarrels among liberals over McCarthyism. Conversely, I demonstrate that conservatives such as William Buckley Jr. and Russell Kirk overcame serious differences on academic freedom to present a united front against liberalism, in and outside of the academy. Finally, I show the difficulty an organization such as the AAUP encounters when defending professional values in a democratic society. -

Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott

University of New England DUNE: DigitalUNE All Theses And Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2017 Theorizing Three Cases Of Otherness In The SU A: Hofstadter, Foucault, And Scott Austin Coco University of New England Follow this and additional works at: http://dune.une.edu/theses Part of the Political Science Commons © 2017 Austin Coco Preferred Citation Coco, Austin, "Theorizing Three Cases Of Otherness In The SAU : Hofstadter, Foucault, And Scott" (2017). All Theses And Dissertations. 136. http://dune.une.edu/theses/136 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at DUNE: DigitalUNE. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses And Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DUNE: DigitalUNE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Austin Coco Dr. Ahmida PSC 491 4/18//17 Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott Austin Coco Coco|1 Dr. Ahmida PSC 491 4/18//17 Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott Introduction This essay examines three cases of otherness: the Italian other in the 1920s, the Communist other during the Red Scare of the 1950s, and the Muslim other in post-2001. The similarities and differences of these cases will be analyzed through Richard Hofstadter’s analysis of the production of otherness for what he calls the paranoid style, Foucault’s analysis of power relations, and James Scott’s analysis of power relations and language. This essay will assess the theoretical methods behind “otherness” that Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott use, the three cases of “otherness”, and the similarities and differences between the cases and how the theoretical mechanisms apply. -

What Kind of Book Is the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution?

What Kind of Book is The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution? eric nelson first read Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the I American Revolution when I was a nineteen-year-old stu- dent in the Harvard History Department’s sophomore tutorial. The text was assigned by my late friend and teacher Mark Kish- lansky, who began our discussion of the book by posing the same deceptively simple question that he asked about each his- toriographical masterwork on the syllabus: “What kind of book is this?” I remember thinking rather smugly that, in this case at least, the question had an obvious and straightforward answer: surely, Ideological Origins was a work of intellectual history— and, more specifically, a contribution to the history of early American political thought. But it now strikes me that this an- swer, while not incorrect, was, and is, quite beside the point. Mark was not asking us a banal question about the genre to which Bailyn’s monograph belonged, but rather a deep one about how Bailyn understood that genre. To present Ideological Origins as a history of political thought is, implicitly, to defend a particular conception of what sort of thing “political thought” is and what its history looks like. What, Mark wished us to pon- der, is that conception? I found myself asking this question with a renewed sense of urgency more than fifteen years later as I grappled witha I am indebted to Bernard Bailyn, Richard Bourke, Jonathan Gienapp, James Hank- ins, Michael Rosen, and Quentin Skinner for extremely helpful comments on this essay. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

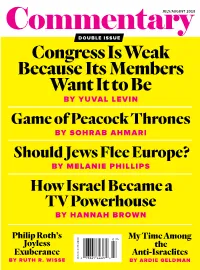

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

The Proud Decades America in War and Peace, 1941-1960 1St Edition Download Free

THE PROUD DECADES AMERICA IN WAR AND PEACE, 1941-1960 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John P Diggins | 9780393956566 | | | | | The Rise And Fall Of The American Left Diggins's interests ranged from the foundations of the United States to the postmodern world. Return to Book Page. Peter rated it it was amazing Jul 28, He was the author of more than a dozen books and thirty articles on widely varied subjects on American intellectual history. He earned a fellowship award from the Guggenheim Fellowship inbecame a resident scholar of the Rockefeller Foundation inand was nominated for the National book Award for History. To ask other readers questions about Ronald Reaganplease sign up. That was contrary to Diggins's personal experience of Reagan "standing for tear gas and police" [4] most likely in reference of the s Berkeley protests. Even if Reagan, like so many others, did The Proud Decades America in War and Peace fully envision exactly how communism would fall, he ended the cold war by creating what Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher insisted was the "essential trust" that would be necessary to allow the peaceful exit of the Soviet Union from history. Published February 17th by W. An obituary reported that Diggins "was "critical of the anticapitalist Left for seeing in the abolition of property an end to oppression" but also "critical of the antigovernment Right for seeing in the elimination of political 1941-1960 1st edition the end of tyranny and the restoration of liberty. Ask Seller a Question. Kristin-Leigh rated it did not like it Oct 02, Community Reviews.