The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science *

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science * George REISCH Received: 31.5.2012 Final version: 30.7.2012 BIBLID [0495-4548 (2012) 27: 75; pp. 323-342] ABSTRACT: Historian Richard Hofstadter’s observations about American cold-war politics are used to contextualize Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and argue that substantive claims about the nature of sci- entific knowledge and scientific change found in Structure were adopted from this cold-war political cul- ture. Keywords: Thomas S. Kuhn; The Structure of Scientific Revolutions ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics;” Cold War; James B. Conant; Brainwashing. RESUMEN: Las observaciones del historiador Richard Hofstadter sobre la política americana en la Guerra Fría se uti- lizan para contextualizar La estructura de las revoluciones científicas de Thomas Kuhn y sostener que algunas afirmaciones fundamentales sobre la naturaleza del conocimiento científico y el cambio científico que se pueden hallar en La estructura fueron adoptadas de esta cultura política de la Guerra Fría. Palabras clave: Thomas S. Kuhn; La estructura de las revoluciones científicas ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”; Guerra Fría; James B. Conant; lavado de cerebro. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant. –Richard Hofstadter (1964, 4) 1. Introduction The conventional wisdom holds that Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions of- fered a revolutionary critique of existing scholarship about science. The book swept aside misconceptions wrought by three kinds of intellectuals—logic-chopping philos- ophers who confused their logical models and formulas with historical fact, Whiggish historians who viewed science’s past through the lenses of the present, and text-book writers whose brief, potted historical introductions obscured science’s dynamic, revo- lutionary history. -

A Measure of Detachment: Richard Hofstadter and the Progressive Historians

A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT: RICHARD HOFSTADTER AND THE PROGRESSIVE HISTORIANS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS By Wiliiam McGeehan May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Harvey Neptune, Department of History Andrew Isenberg, Department of History ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Richard Hofstadter's innovations in historical method arose as a critical response to the Progressive historians, particularly to Charles Beard. Hofstadter's first two books were demonstrations of the inadequacy of Progressive methodology, while his third book (the Age of Reform) showed the potential of his new way of writing history. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................i CHAPTER 1. A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT..........................................................................1 2. SOCIAL DARWINISM IN AMERICAN THOUGHT………………………………………………26 3. THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION…………………………………………………………..52 4. THE AGE OF REFORM…………………………………………………………………………………….100 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………139 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..144 CHAPTER ONE A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT Great thinkers often spend their early years in rebellion against the teachers from whom they have learned the most. Freud would say they live out a form of the Oedipal archetype, that son must murder his father at least a little bit if he is ever to become his own man. -

Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott

University of New England DUNE: DigitalUNE All Theses And Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 5-1-2017 Theorizing Three Cases Of Otherness In The SU A: Hofstadter, Foucault, And Scott Austin Coco University of New England Follow this and additional works at: http://dune.une.edu/theses Part of the Political Science Commons © 2017 Austin Coco Preferred Citation Coco, Austin, "Theorizing Three Cases Of Otherness In The SAU : Hofstadter, Foucault, And Scott" (2017). All Theses And Dissertations. 136. http://dune.une.edu/theses/136 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at DUNE: DigitalUNE. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses And Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DUNE: DigitalUNE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Austin Coco Dr. Ahmida PSC 491 4/18//17 Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott Austin Coco Coco|1 Dr. Ahmida PSC 491 4/18//17 Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott Introduction This essay examines three cases of otherness: the Italian other in the 1920s, the Communist other during the Red Scare of the 1950s, and the Muslim other in post-2001. The similarities and differences of these cases will be analyzed through Richard Hofstadter’s analysis of the production of otherness for what he calls the paranoid style, Foucault’s analysis of power relations, and James Scott’s analysis of power relations and language. This essay will assess the theoretical methods behind “otherness” that Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott use, the three cases of “otherness”, and the similarities and differences between the cases and how the theoretical mechanisms apply. -

What Kind of Book Is the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution?

What Kind of Book is The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution? eric nelson first read Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the I American Revolution when I was a nineteen-year-old stu- dent in the Harvard History Department’s sophomore tutorial. The text was assigned by my late friend and teacher Mark Kish- lansky, who began our discussion of the book by posing the same deceptively simple question that he asked about each his- toriographical masterwork on the syllabus: “What kind of book is this?” I remember thinking rather smugly that, in this case at least, the question had an obvious and straightforward answer: surely, Ideological Origins was a work of intellectual history— and, more specifically, a contribution to the history of early American political thought. But it now strikes me that this an- swer, while not incorrect, was, and is, quite beside the point. Mark was not asking us a banal question about the genre to which Bailyn’s monograph belonged, but rather a deep one about how Bailyn understood that genre. To present Ideological Origins as a history of political thought is, implicitly, to defend a particular conception of what sort of thing “political thought” is and what its history looks like. What, Mark wished us to pon- der, is that conception? I found myself asking this question with a renewed sense of urgency more than fifteen years later as I grappled witha I am indebted to Bernard Bailyn, Richard Bourke, Jonathan Gienapp, James Hank- ins, Michael Rosen, and Quentin Skinner for extremely helpful comments on this essay. -

David Greenberg

DAVID GREENBERG Professor of History Professor of Journalism & Media Studies Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646.504.5071 • [email protected] Education. Columbia University, New York, NY. PhD, History. 2001. MPhil, History. 1998. MA, History. 1996. Yale University, New Haven, CT. BA, History. 1990. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Distinction in the major. Academic Positions. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2016- . Associate Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2008-2016. Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism & Media Studies. 2004-2008. Appointment to the Graduate Faculty, Department of History. 2004-2008. Affiliation with Department of Political Science. Affiliation with Department of Jewish Studies. Affiliation with Eagleton Institute of Politics. Columbia University, New York, NY. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of History, Spring 2014. Yale University, New Haven, CT. Lecturer, Department of History and Political Science. 2003-04. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Cambridge MA. Visiting Scholar. 2002-03. Columbia University, New York, NY. Lecturer, Department of History. 2001-02. Teaching Assistant, Department of History. 1996-99. Greenberg, CV, p. 2. Other Journalism and Professional Experience. Politico Magazine. Columnist and Contributing Editor, 2015- The New Republic. Contributing Editor, 2006-2014. Moderator, “The Open University” blog, 2006-07. Acting Editor (with Peter Beinart), 1996. Managing Editor, 1994-95. Reporter-researcher, 1990-91. Slate Magazine. Contributing editor and founder of “History Lesson” column, the first regular history column by a professional historian in the mainstream media. 1998-2015. Staff editor, culture section, 1996-98. The New York Times. -

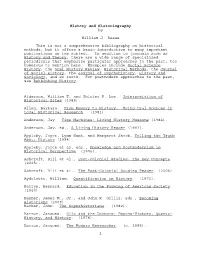

History and Historiography by William J. Reese This Is Not A

History and Historiography by William J. Reese This is not a comprehensive bibliography on historical methods, but it offers a basic introduction to many important publications on the subject. In addition to journals such as History and Theory, there are a wide range of specialized periodicals that emphasize particular approaches to the past, too numerous to mention here. Examples include Social Science History, the Oral History Review, Historical Methods, the Journal of Social History, the Journal of Psychohistory, History and Sociology, and so forth. For postmodern approaches to the past, see Rethinking History. Alderson, William T. and Shirley P. Low. Interpretation of Historical Sites (1985). Allen, Barbara. From Memory to History: Using Oral Sources in Local Historical Research. (1981). Anderson, Jay. Time Machines: Living History Museums (1984). Anderson, Jay, ed., A Living History Reader (1991). Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History (1994). Appleby, Joyce et al, eds., Knowledge and Postmodernism in Historical Perspective. (1996). Ashcroft, Bill et al., Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts. (2005). Ashcroft, Bill et al., The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. (2006) Aydelotte, William. Quantification in History. (1971). Bailyn, Bernard. Education in the Forming of American Society. (1960) Banner, James M., Jr., and John R. Gillis, eds., Becoming Historians (2009). Barker, John. The Superhistorians. (1982). Barzun, Jacques. Clio and the Doctors: Psycho-History, Quanto- History, and History. (1976). Barzun, Jacques. The Modern Researcher. (c. 1985). 1 Barzun, Jacques. Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers. (1985). Beauchamp, Edward. Dissertations in the History of Education, 1970-1980. (1985). Becker, Carl. Everyman His Own Historian. -

The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter 45

The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter 45 The Conservatism of Richard Hofstadter Ryan Coates Third Year Undergraduate, Durham University ‘We have all been taught to regard it as more or less “natural” for young dissenters to become conservatives as they grow older.’ Richard Hofstadter So proved to be the case for the author of this statement, the outstanding American historian of the twentieth century, Richard Hofstadter (1916-70). This assertion challenges the dominant orthodox portrayal of Hofstadter as the iconic public intellectual of post-war American liberalism. The orthodox interpretation, supported by biographer David Brown and historians Arthur Schlesinger and Sean Wilentz, demonstrates Hofstadter’s ideological progression from thirties radical, briefly a member of the Communist Party, to fifties liberal credited as the founder of consensus history.1 This interpretation draws upon Hofstadter’s most political works, includingThe American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It (1948), The Age of Reform (1955) and most prominently, the essays collected in The Paranoid Style in American Politics (1964), to reveal an apparent all-encompassing hostility toward conservatism. The revisionist interpretation, advanced by Hofstadter’s fellow New York intellectual Alfred Kazin and historians Robert Collins, Daniel Walker Howe and Peter Elliott Finn, challenges this one-dimensional portrayal of Hofstadter’s complex relationship to conservatism.2 Rather than flourishing into the iconic historian of American liberalism, the revisionists contend, Hofstadter’s intellectual development represented a gradual transition that had, by the end of his shortened life, culminated in a conversion to Burkean conservatism. Indeed, Kazin’s description of Hofstadter as a ‘secret conservative in a radical period’ encourages parallels 1 David S. -

HISTORY Copy.Pages

! ! ! QUOTES ON HISTORY ! ! Civilization is a stream with banks. The stream is sometimes filled with blood from people killing stealing, shouting and doing the things historians usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed people build homes, make love, raise children, sing songs, write poetry and even whittle statues. The story of civilization is the story of what happened on the banks. Historians are pessimists because they ignore the banks for the river. ! --Will Durant The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like. ! —E. L. Doctorow History gives us the facts, sort of, but from literary works we can learn what the past smelled like, sounded like, and felt like, the forgotten gritty details of a lost era. Literature brings us as close as we can come to reinhabiting the past. By re- claiming this use of literature in the classroom, perhaps we can move away from the political agitation that has been our bread and butter—or porridge and hardtack— for the last 30 years. ! —Scott Herring Great novelists are the true historians of the times in which they live. Stop and think about it for a minute and I’m sure you’ll find that you didn’t get your impres- sions of what life was like here and abroad in the last 300 years from the history books—but from the novels of such literary titans as Hardy, Dostoevsky, Dickens, Sinclair Lewis, Jane Austen, and Tolstoy. Writers like these had a kind of extrasen- sory perception which enabled them to see beneath the surface of the age—and, of course, the genius to bring people and events to life in stories that enthralled read- ers of their own time as well as later generations. -

The Warren Court: a Distant Mirror? Part One—The Chief

Antitrust , Vol. 33, No. 2, Spring 2019. © 2019 by the American Bar Association. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. This information or any portion thereof may not be copied or disseminated in any form or by any means or stored in an electronic database or retrieval system without the express written consent of the American Bar Association. established the one-man, one-vote principle, expanded the rights of criminal defendants, bolstered free speech, and protected the right to disseminate and access birth control information. 3 Without the Warren Court, the United States would be a very dif - ferent place than it is today, with Americans having far fewer rights than they now do. During Warren’s tenure, in the area of antitrust, the Supreme Court continued down the path it had pursued since the end of World War II under the leadership of his two immediate prede - cessors, Harlan Fiske Stone and Carl Vinson. Under both Chief Justices, the Court established a record of voting consistently in favor of both the government and private plaintiffs in antitrust TRUST BUSTERS cases. 4 The most notable of the Court’s post-World War II deci - sions in support of strong antitrust enforcement were its 1946 ruling in American Tobacco ,5 finding the country’s leading tobac - The Warren Court: co producers guilty of a criminal violation of Section 2 of the Sherman Act for conspiring to raise cigarette prices despite A Distant Mirror? declining demand; its 1948 rulings in Griffit h 6 and Paramount Pictures ,7 requiring the restructuring of the movie industry after Part On e—The Chief: finding that vertical integration by filmmakers into theatre own - ership was an act of monopolization in violation of Section 2; and its 1951 ruling in Timken Roller Bearing ,8 finding a market allo - Earl Warren cation agreement between U.S. -

Thomas Jefferson and the Agrarian Myth: a Reappraisal of Sources

FACULTAD de FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO de FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Grado en Estudios Ingleses TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO Thomas Jefferson and the Agrarian Myth: A Reappraisal of Sources José Augusto Salatino Indelicato Tutor: Anunciación Carrera de la Red 2013-2014 1 2 ABSTRACT This dissertation evaluates Thomas Jefferson’s agrarianism using Richard Hofstadter’s notion of the ‘Agrarian Myth’ (The Age of Reform, 1955). A literature review of studies on Jefferson’s claims for the rural life reveals two contesting views: one favorable to his agrarianism as a moral vision, another condemnatory against the stateman’s eventual pro-capitalist turn for commerce and manufacture. The simplistic reduction both positions make of Jefferson’s motivations to ‘morality’ in opposition to ‘politics’ and ‘economy’ asks for a reappraisal of sources. Here follows a new analysis of Jefferson’s addresses, writings and correspondece dealing with agrarian life and manufacture. The results indicate with Holowchak (2011) that the crux of the debate should not be ‘ethics’ but ‘morality’, but, contrary to him, that Jefferson’s ability to hide the pragmatic use of manufacture under the defense of non-commercial values, may be deemed ‘moral’ (acting depending on circumstance), precisely because it is ‘politica l’ and ‘economic’. KEYWORDS: Thomas Jefferson – Agrarian Myth – Jefferson’s Writings – Morality – Politics – Economy. Este trabajo analiza la presencia en los escritos de Thomas Jefferson de los elementos básicos que componen la noción ‘Mito Agrario’ ideada por Hofstadter (The Age of Reform, 1955). El repaso de las publicaciones existentes en torno el pensamiento de lo agrario en Jefferson muestra que unas aprueban sus actuaciones y otras condenan el giro pro-capitalista que dio en favor del comercio y la manufactura. -

Power, Dissent, and the Contest of Intellectual Virtues in the 1950S

The Anxiety of Irrelevance: Power, Dissent, and the Contest of Intellectual Virtues in the 1950s Allon Brann Senior Thesis April 2010 Advisor: Professor William Leach Second Reader: Professor Casey Blake 1 Acknowledgments If there is one thing about this essay that most satisfies me, it is that the process of writing it felt like a fitting conclusion to my undergraduate career. In conceiving of my project, I wanted to draw out the issues that most challenged me over four years of study, and to try to interrogate them, side by side, one last time. I want to say at the outset, then, that I believe each one of my extraordinary teachers at Columbia has contributed to this project. There has been no greater intellectual pleasure over the last four years than discovering unforeseen connections between the different texts and problems that I had the opportunity to investigate with each of them. There are, of course, a few whom I must identify here individually. Professor William Leach guided our seminar with great patience and taught me much about good historical writing. In addition to serving as my second reader for this essay, Professor Casey Blake laid the groundwork for my exploration of American intellectual history. He introduced me to many of the figures who have most inspired—and at times, troubled—me in my study of the past, and with whom I hope to continue to engage long after the completion of this project. I am grateful, as well, to Professor Ross Posnock, whose course pushed me to question the role of the thinker in American society, past and present. -

Adam Hochschild’S Bury the Chains, on the Abolition of the British Slave Trade and Slavery

2 Historically Speaking • March/April 2008 DO YOU NEED A LICENSE TO HISTORICALLY SPEAKING March/April 2008 Vol. IX No. 4 PRACTICE HISTORY? CONTENTS ONE YEAR AGO, WE PUBLISHED MAUREEN OGLE’S WINSOME ACCOUNT OF LEAVING Do You Need a License to academic history to “go popular.” Two issues later, the Historical Society’s president, Eric Arnesen, himself a frequent writer of reviews for the Chicago Tribune, wrote an essay expressing concern that so-called popular historians do not make sufficient Practice History? effort to incorporate the fruits of academic historical scholarship in their books. Arnesen selected two books to illustrate his con- Practicing History without a License 2 cern. One of them was Adam Hochschild’s Bury the Chains, on the abolition of the British slave trade and slavery. Hochschild, Adam Hochschild an accomplished writer and editor, responded to Arnesen with a thoughtful letter that we published in the November/December Responses to Adam Hochschild 2007 issue. He also suggested that he would welcome further discussion on the relationship between popular and academic his- tory. We invited Hochschild to write a think-piece, “Practicing History without a License.” Historically Speaking editor H. W. Brands 6 Donald A. Yerxa then recruited a good number of prominent historians and editors to respond to Hochschild. These include John Demos 7 several authors of bestselling history books (one of whom won the Pulitzer Prize), editors of publications geared to general read- Joseph J. Ellis 8 ers, and an editor of one of the world’s leading academic presses (which also has a trade division).