Theorizing Three Cases of Otherness in the USA: Hofstadter, Foucault, and Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pete Seegerhas Always Walked the Road Less Traveled. a Tall, Lean Fellow

Pete Seegerhas always walked the road less traveled. A tall, lean fellow with long arms and legs, high energy and a contagious joy of spjrit, he set everything in motion, singing in that magical voice, his head thrown back as though calling to the heavens, makingyou see that you can change the world, risk everything, do your best, cast away stones. “Bells of Rhymney,” “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?,” “ One Grain of Sand,” “ Oh, Had I a Golden Thread” ^ songs Right, from top: Seeger, Bob Dylan, Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie (from left) at the Woody Guthrie Memorial Concert at Carnegie Hail, 1967; filming “Wasn’t That a Time?," a movie of the Weavers’ 19 8 0 reunion; Seeger with banjo; at Red Above: The Weavers in the early ’50s - Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert and Fred Hellerman (from left). Left: Seeger singing on a Rocks, in hillside in El Colorado, 1983; Cerrito, C a l|p in singing for the early '60s. Eleanor Roosevelt, et al., at the opening of the Washington Labor Canteen, 1944; aboard the “Clearwater” on his beloved Hudson River; and a recent photo of Seeger sporting skimmer (above), Above: The Almanac Singers in 1 9 4 1 , with Woody Guthrie on the far left, and Seeger playing banjo. Left: Seeger with his mother, the late Constance Seeger. PHOTOGRAPHS FROM THE COLLECTION OF HAROLD LEVENTHAL AND THE WOODY GUTHRIE ARCHIVES scattered along our path made with the Weavers - floor behind the couch as ever, while a retinue of like jewels, from the Ronnie Gilbert, Fred in the New York offices his friends performed present into the past, and Hellerman and Lee Hays - of Harold Leventhal, our “ Turn Turn Turn,” back, along the road to swept into listeners’ mutual manager. -

Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment

Shirley Papers 48 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title Research Materials Crime, Law Enforcement, and Punishment Capital Punishment 152 1 Newspaper clippings, 1951-1988 2 Newspaper clippings, 1891-1938 3 Newspaper clippings, 1990-1993 4 Newspaper clippings, 1994 5 Newspaper clippings, 1995 6 Newspaper clippings, 1996 7 Newspaper clippings, 1997 153 1 Newspaper clippings, 1998 2 Newspaper clippings, 1999 3 Newspaper clippings, 2000 4 Newspaper clippings, 2001-2002 Crime Cases Arizona 154 1 Cochise County 2 Coconino County 3 Gila County 4 Graham County 5-7 Maricopa County 8 Mohave County 9 Navajo County 10 Pima County 11 Pinal County 12 Santa Cruz County 13 Yavapai County 14 Yuma County Arkansas 155 1 Arkansas County 2 Ashley County 3 Baxter County 4 Benton County 5 Boone County 6 Calhoun County 7 Carroll County 8 Clark County 9 Clay County 10 Cleveland County 11 Columbia County 12 Conway County 13 Craighead County 14 Crawford County 15 Crittendon County 16 Cross County 17 Dallas County 18 Faulkner County 19 Franklin County Shirley Papers 49 Research Materials, Crime Series Inventory Box Folder Folder Title 20 Fulton County 21 Garland County 22 Grant County 23 Greene County 24 Hot Springs County 25 Howard County 26 Independence County 27 Izard County 28 Jackson County 29 Jefferson County 30 Johnson County 31 Lafayette County 32 Lincoln County 33 Little River County 34 Logan County 35 Lonoke County 36 Madison County 37 Marion County 156 1 Miller County 2 Mississippi County 3 Monroe County 4 Montgomery County -

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science *

The Paranoid Style in American History of Science * George REISCH Received: 31.5.2012 Final version: 30.7.2012 BIBLID [0495-4548 (2012) 27: 75; pp. 323-342] ABSTRACT: Historian Richard Hofstadter’s observations about American cold-war politics are used to contextualize Thomas Kuhn’s The Structure of Scientific Revolutions and argue that substantive claims about the nature of sci- entific knowledge and scientific change found in Structure were adopted from this cold-war political cul- ture. Keywords: Thomas S. Kuhn; The Structure of Scientific Revolutions ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics;” Cold War; James B. Conant; Brainwashing. RESUMEN: Las observaciones del historiador Richard Hofstadter sobre la política americana en la Guerra Fría se uti- lizan para contextualizar La estructura de las revoluciones científicas de Thomas Kuhn y sostener que algunas afirmaciones fundamentales sobre la naturaleza del conocimiento científico y el cambio científico que se pueden hallar en La estructura fueron adoptadas de esta cultura política de la Guerra Fría. Palabras clave: Thomas S. Kuhn; La estructura de las revoluciones científicas ; Richard Hofstadter; “The Paranoid Style in American Politics”; Guerra Fría; James B. Conant; lavado de cerebro. It is the use of paranoid modes of expression by more or less normal people that makes the phenomenon significant. –Richard Hofstadter (1964, 4) 1. Introduction The conventional wisdom holds that Thomas Kuhn’s Structure of Scientific Revolutions of- fered a revolutionary critique of existing scholarship about science. The book swept aside misconceptions wrought by three kinds of intellectuals—logic-chopping philos- ophers who confused their logical models and formulas with historical fact, Whiggish historians who viewed science’s past through the lenses of the present, and text-book writers whose brief, potted historical introductions obscured science’s dynamic, revo- lutionary history. -

A Measure of Detachment: Richard Hofstadter and the Progressive Historians

A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT: RICHARD HOFSTADTER AND THE PROGRESSIVE HISTORIANS A Thesis Submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS By Wiliiam McGeehan May 2018 Thesis Approvals: Harvey Neptune, Department of History Andrew Isenberg, Department of History ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Richard Hofstadter's innovations in historical method arose as a critical response to the Progressive historians, particularly to Charles Beard. Hofstadter's first two books were demonstrations of the inadequacy of Progressive methodology, while his third book (the Age of Reform) showed the potential of his new way of writing history. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT.......................................................................................................................i CHAPTER 1. A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT..........................................................................1 2. SOCIAL DARWINISM IN AMERICAN THOUGHT………………………………………………26 3. THE AMERICAN POLITICAL TRADITION…………………………………………………………..52 4. THE AGE OF REFORM…………………………………………………………………………………….100 5. CONCLUSION…………………………………………………………………………………………………139 BIBLIOGRAPHY…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..144 CHAPTER ONE A MEASURE OF DETACHMENT Great thinkers often spend their early years in rebellion against the teachers from whom they have learned the most. Freud would say they live out a form of the Oedipal archetype, that son must murder his father at least a little bit if he is ever to become his own man. -

What Kind of Book Is the Ideological Origins of the American Revolution?

What Kind of Book is The Ideological Origins of the American Revolution? eric nelson first read Bernard Bailyn’s The Ideological Origins of the I American Revolution when I was a nineteen-year-old stu- dent in the Harvard History Department’s sophomore tutorial. The text was assigned by my late friend and teacher Mark Kish- lansky, who began our discussion of the book by posing the same deceptively simple question that he asked about each his- toriographical masterwork on the syllabus: “What kind of book is this?” I remember thinking rather smugly that, in this case at least, the question had an obvious and straightforward answer: surely, Ideological Origins was a work of intellectual history— and, more specifically, a contribution to the history of early American political thought. But it now strikes me that this an- swer, while not incorrect, was, and is, quite beside the point. Mark was not asking us a banal question about the genre to which Bailyn’s monograph belonged, but rather a deep one about how Bailyn understood that genre. To present Ideological Origins as a history of political thought is, implicitly, to defend a particular conception of what sort of thing “political thought” is and what its history looks like. What, Mark wished us to pon- der, is that conception? I found myself asking this question with a renewed sense of urgency more than fifteen years later as I grappled witha I am indebted to Bernard Bailyn, Richard Bourke, Jonathan Gienapp, James Hank- ins, Michael Rosen, and Quentin Skinner for extremely helpful comments on this essay. -

“Talking Union”--The Almanac Singers (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Cesare Civetta (Guest Post)*

“Talking Union”--The Almanac Singers (1941) Added to the National Registry: 2010 Essay by Cesare Civetta (guest post)* 78rpm album package Pete Seeger, known as the “Father of American Folk music,” had a difficult time of it as a young, budding singer. While serving in the US Army during World War II, he wrote to his wife, Toshi, “Every song I started to write and gave up was a failure. I started to paint because I failed to get a job as a journalist. I started singing and playing more because I was a failure as a painter. I went into the army because I was having more and more failure musically.” But he practiced his banjo for hours and hours each day, usually starting as soon as he woke in the morning, and became a virtuoso on the instrument, and even went on to invent the “long-neck banjo.” The origin of the Almanacs Singers’ name, according to Lee Hays, is that every farmer's home contains at least two books: the Bible, and the Almanac! The Almanacs Singers’ first job was a lunch performance at the Jade Mountain Restaurant in New York in December of 1940 where they were paid $2.50! The original members of the group were Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Millard Campbell, John Peter Hawes, and later Woody Guthrie. Initially, Seeger used the name Pete Bowers because his dad was then working for the US government and he could have lost his job due to his son’s left-leaning politically charged music. The Singers sang anti-war songs, songs about the draft, and songs about President Roosevelt, frequently attacking him. -

The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption

The Mad, Mad World of Textbook Adoption Foreword by Chester E. Finn, Jr. Introduction by Diane Ravitch 1627 K Street Northwest Suite 600 Washington D.C. 20006 (202) 223-5452 (202) 223-9226 Fax www.edexcellence.net September 2004 The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is a nonprofit organization that conducts research, issues publications, and directs action projects in elementary/secondary education reform at the national level and in Dayton, Ohio. It is affiliated with the Thomas B. Fordham Foundation. Further information is at www.edexcellence.net/institute, or write us at 1627 K Street Northwest Suite 600 Washington, D.C. 20006 This report is available in full on the web site. Additional copies can be ordered at www.edexcellence.net/institute/publication/order.cfm or by calling 410-634-2400. The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is neither connected with nor sponsored by Fordham University. Cover illustration by Thomas Fluharty, all rights reserved Design by Katherine Rybak Torres, all rights reserved Printed by District Creative Printing, Upper Marlboro, Maryland Executive Summary extbook Adoption: The process, in place in twenty-one states, of Treviewing textbooks according to state guidelines and then man- dating specific books that schools must use, or lists of approved text- books that schools must choose from. Textbook Adoption Is Bad for Students and Schools It consistently produces second-rate textbooks that replicate the same flaws and failings over and over again. Adoption states perform poorly on national tests, and the market incentives caused by the adop- tion process are so skewed that lively writing and top-flight scholarship are discouraged. -

The Roots of the Protest Era: Mccarthyism and the Artist's Voice in 1950S America

THE ROOTS OF THE PROTEST ERA: MCCARTHYISM AND THE ARTIST’S VOICE IN 1950S AMERICA OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How were musicians and artists affected by McCarthyism in 1950s America? OVERVIEW The so-called “Protest Era” in the United States is largely associated with the Civil Rights movement and anti-war demonstrations of the 1960s. But the roots of the protest era, and even some of the songs associated with it, came out of the late 1940s, during the early years of the Cold War. By the end of World War II in 1945, America’s diplomatic relationship with the Soviet Union, once its wartime ally, had grown strained. During the late 1940s, the Soviets expanded their influence across Eastern Europe and built up a stockpile of nuclear weapons—technology that had previously been in the exclusive possession of the U.S. military. Many people in the United States came to view the Soviets, and the Communist Party that controlled the Soviet Union, as a threat to America’s newfound economic prosperity and position as world leader. In that tension between Soviet and American powers, the Cold War was born—and with it, the U.S. entered into an era in which the flipside of an unprecedented economic boom and rise in world power was the “Red Scare,” a widespread fear and suspicion of Soviets and their ideas, which many viewed as a potential threat to American life. At the center of the Red Scare was Senator Joseph R. McCarthy, a Republican from Wisconsin, who by 1950 had become the face of a national campaign to identify communists in American society. -

American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 12-2015 If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left Sarah C. Kerley East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kerley, Sarah C., "If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left" (2015). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2614. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/2614 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left —————————————— A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Masters of Arts in History —————————————— by Sarah Caitlin Kerley December 2015 —————————————— Dr. Elwood Watson, Chair Dr. Daryl A. Carter Dr. Dinah Mayo-Bobee Keywords: Folk Music, Communism, Radical Left ABSTRACT If I Had a Hammer: American Folk Music and the Radical Left by Sarah Caitlin Kerley Folk music is one of the most popular forms of music today; artists such as Mumford and Sons and the Carolina Chocolate Drops are giving new life to an age-old music. -

Woody Guthrie and the Writing of “Balladsongs” � �Mark F

ISSN 2053-8804 Woody Guthrie Annual, 3 (2017): Fernandez: Guthrie and the Writing of “Balladsongs” “The Only Way That I Could Cry”: Woody Guthrie and the Writing of “Balladsongs” ! !Mark F. Fernandez Woody Guthrie wrote about everything. He even coined a motto about it at the end of his most famous lyric sheet: “All you can write is what you see.”1 And he saw just about everything there was to see of the mid-twentieth-century American experience. His famous travels took him throughout most of the then forty-eight states, and like so many Americans of his day, World War II acquainted him with life on the high seas, the coasts of Africa, and parts of Europe. As he wrote about the things he saw and the causes he came to embrace, Guthrie developed an approach to the songwriting process that he shared with anyone who would listen and even some that probably did not want his advice at all. That approach has gone on to influence generations of songwriters ever since — their legion is often dubbed “Woody’s Children.” Peers like Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Ronnie Gilbert, and Fred Hellerman, who would go on to form the influential folk/pop group The Weavers, recorded Woody’s songs, emulated his songwriting process in their own work, and helped spark a “folk revival” that energized the 1950s and 60s. Young entertainers like Ramblin’ Jack Elliot and Bob Dylan sought out and copied Guthrie as they developed their own craft. More recently, artists like Billy Bragg, Jay Farrar, and Jonatha Brooke have counted Guthrie as a major influence and have even adapted his unpublished lyrics in some of their recordings as well as incorporating his “all you can write is what you see” mentality into their own creative processes. -

David Greenberg

DAVID GREENBERG Professor of History Professor of Journalism & Media Studies Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey 4 Huntington Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 646.504.5071 • [email protected] Education. Columbia University, New York, NY. PhD, History. 2001. MPhil, History. 1998. MA, History. 1996. Yale University, New Haven, CT. BA, History. 1990. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. Distinction in the major. Academic Positions. Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ. Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2016- . Associate Professor, Departments of History and Journalism & Media Studies. 2008-2016. Assistant Professor, Department of Journalism & Media Studies. 2004-2008. Appointment to the Graduate Faculty, Department of History. 2004-2008. Affiliation with Department of Political Science. Affiliation with Department of Jewish Studies. Affiliation with Eagleton Institute of Politics. Columbia University, New York, NY. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of History, Spring 2014. Yale University, New Haven, CT. Lecturer, Department of History and Political Science. 2003-04. American Academy of Arts & Sciences, Cambridge MA. Visiting Scholar. 2002-03. Columbia University, New York, NY. Lecturer, Department of History. 2001-02. Teaching Assistant, Department of History. 1996-99. Greenberg, CV, p. 2. Other Journalism and Professional Experience. Politico Magazine. Columnist and Contributing Editor, 2015- The New Republic. Contributing Editor, 2006-2014. Moderator, “The Open University” blog, 2006-07. Acting Editor (with Peter Beinart), 1996. Managing Editor, 1994-95. Reporter-researcher, 1990-91. Slate Magazine. Contributing editor and founder of “History Lesson” column, the first regular history column by a professional historian in the mainstream media. 1998-2015. Staff editor, culture section, 1996-98. The New York Times. -

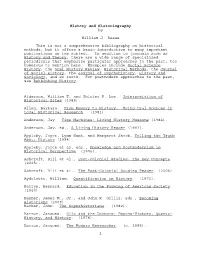

History and Historiography by William J. Reese This Is Not A

History and Historiography by William J. Reese This is not a comprehensive bibliography on historical methods, but it offers a basic introduction to many important publications on the subject. In addition to journals such as History and Theory, there are a wide range of specialized periodicals that emphasize particular approaches to the past, too numerous to mention here. Examples include Social Science History, the Oral History Review, Historical Methods, the Journal of Social History, the Journal of Psychohistory, History and Sociology, and so forth. For postmodern approaches to the past, see Rethinking History. Alderson, William T. and Shirley P. Low. Interpretation of Historical Sites (1985). Allen, Barbara. From Memory to History: Using Oral Sources in Local Historical Research. (1981). Anderson, Jay. Time Machines: Living History Museums (1984). Anderson, Jay, ed., A Living History Reader (1991). Appleby, Joyce, Lynn Hunt, and Margaret Jacob, Telling the Truth About History (1994). Appleby, Joyce et al, eds., Knowledge and Postmodernism in Historical Perspective. (1996). Ashcroft, Bill et al., Post-Colonial Studies: The Key Concepts. (2005). Ashcroft, Bill et al., The Post-Colonial Studies Reader. (2006) Aydelotte, William. Quantification in History. (1971). Bailyn, Bernard. Education in the Forming of American Society. (1960) Banner, James M., Jr., and John R. Gillis, eds., Becoming Historians (2009). Barker, John. The Superhistorians. (1982). Barzun, Jacques. Clio and the Doctors: Psycho-History, Quanto- History, and History. (1976). Barzun, Jacques. The Modern Researcher. (c. 1985). 1 Barzun, Jacques. Simple and Direct: A Rhetoric for Writers. (1985). Beauchamp, Edward. Dissertations in the History of Education, 1970-1980. (1985). Becker, Carl. Everyman His Own Historian.