"Commentary" in American Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Periodicalspov.Pdf

“Consider the Source” A Resource Guide to Liberal, Conservative and Nonpartisan Periodicals 30 East Lake Street ∙ Chicago, IL 60601 HWC Library – Room 501 312.553.5760 ver heard the saying “consider the source” in response to something that was questioned? Well, the same advice applies to what you read – consider the source. When conducting research, bear in mind that periodicals (journals, magazines, newspapers) may have varying points-of-view, biases, and/or E political leanings. Here are some questions to ask when considering using a periodical source: Is there a bias in the publication or is it non-partisan? Who is the sponsor (publisher or benefactor) of the publication? What is the agenda of the sponsor – to simply share information or to influence social or political change? Some publications have specific political perspectives and outright state what they are, as in Dissent Magazine (self-described as “a magazine of the left”) or National Review’s boost of, “we give you the right view and back it up.” Still, there are other publications that do not clearly state their political leanings; but over time have been deemed as left- or right-leaning based on such factors as the points- of-view of their opinion columnists, the make-up of their editorial staff, and/or their endorsements of politicians. Many newspapers fall into this rather opaque category. A good rule of thumb to use in determining whether a publication is liberal or conservative has been provided by Media Research Center’s L. Brent Bozell III: “if the paper never met a conservative cause it didn’t like, it’s conservative, and if it never met a liberal cause it didn’t like, it’s liberal.” Outlined in the following pages is an annotated listing of publications that have been categorized as conservative, liberal, non-partisan and religious. -

PRESCRIPTION and PREJUDICE Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology

PRESCRIPTION AND PREJUDICE REMEMBERING A GOTHIC CONSERVATISM Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology W. Wesley McDonald Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press, 2004 $44.95 264 pp. Reviewed by David Wilson s a copy clerk for my hometown newspaper years ago, I asked the token conservative on the editorial board whom I should read to pursue my A emerging interest in political conservatism. “Russell Kirk,” he said. “Who’s that?” I asked. “A crustacean,” he answered dryly, without taking his eyes off his computer screen. The editorialist’s confi dent citation of Kirk as a primary conserva- tive authority—quickly followed by a half-joking dismissal of his current relevance—captures the Kirk legacy. Mainstream conservative fi gures will often dutifully list Kirk’s works as among those to be studied, especially the seminal The Conservative Mind, published by Henry Regnery in 1953. But what traces of Kirk’s thought inform the “conservative” policy positions of today are diffi cult to detect. Russell Kirk was part custodian, part critic. From Aristotle to Burke and beyond, he absorbed and carried forward those elements of Western thought he deemed wisest. To these he added his own, notably decisive rejections of “atomistic” individualism, economic and social leveling, and dogmatic laissez faire. The giddier thinking of the Enlightenment, especially Benthamite utilitarianism, came under his harsh scrutiny. He famously set forth the “six canons of conservative thought,” and advanced conservatism as the rejection of political programs that presume the easy malleability of human nature —really, his defi nition of “ideology.” In Russell Kirk and the Age of Ideology, W. -

Religion and Innovation in Human Affairs (RIHA) Religion And

Religion and Innovation in Human Affairs (RIHA) Exploring the Role of Religion in the Origins of Novelty and the Diffusion of Innovation in the Progress of Civilizations Religion and Innovation: Naturalism, Scientific Progress, and Secularization Protestantism? Reflections in Advance of the 500th Anniversary of the Protestant Reformation ($75,000). Gordon College. PIs: Thomas Albert Howard (Gordon College) and Mark A. Noll (University of Notre Dame) With an eye on the approaching quincentennial, of the Protestant Reformation, the project has engaged in a fundamental inquiry into the historical significance of Protestantism, its heterogeneous trajectories of influence, and their relationship to forces of social innovation, political development, and religious change in the modern West and across the globe. The quincentennial of the Protestant Reformation in 2017 will bring into public view longstanding scholarly debates, interpretations and their revisions—along with lingering confessional animosities and more recent ecumenical overtures. For Western Christianity, a moment of historical recollection on this scale has not presented itself in recent memory. Acts of commemoration can be enlisted to reflect, shape, and introduce novel forces into history. They were not simply conduits or transmitters of the old, but definers and harbingers of the new. In this sense, we might view the past commemorations of the Reformation as being not unlike the sixteenth-century Reformation itself: a series of acts motivated by the desire of retrieval and restoration that, in the final analysis, left a legacy of profound change, disruption, and innovation in human history. Major Outputs: Books: • Howard, Thomas Albert. The Pope and the Professor: Pius IX, Ignaz von Döllinger, and the Quandary of the Modern Age (accepted, Oxford University Press) • Howard, Thomas A. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education

Advance Praise for Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education “The space for dissent and real democratic debate is quickly shrinking both in public life and academic institutions in western democracies. Today, the cries of ‘fake news’ make the loudest (though rarely the best informed) voices the site of authority and truth. This volume helps readers in higher education ask critical and conscious questions about what it means to con- tend for truth. It is an important and significant read for those who want the intellectual space to remain a terrain for thinkers.” —Gloria Ladson-Billings, author of The Dreamkeepers “This deep and layered book maps the path toward a university based on eth- ics and justice rather than corporate needs and military standards. It reaches anyone who wants to understand the social, political, and economic trends that define our times. It is an outstanding contribution to the scholarship on higher education.” —William Ayers, author of Teaching with Conscience in an Imperfect World “Dissident Knowledge in Higher Education is a rich and multi-layered examina- tion of the impact of corporatization on our universities, as well as how they can be reclaimed. Highly recommended.” —James Turk, editor of Academic Freedom in Conflict dissident knowledge in higher education edited with an introduction by marc spooner & James MCNinch © 2018 University of Regina Press “An Interview with Noam Chomsky” © 2016 Noam Chomsky, Marc Spooner, and James McNinch This publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommerical- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. See www.creativecommons.org. The text may be reproduced for non-commercial purposes, provided that credit is given to the original author. -

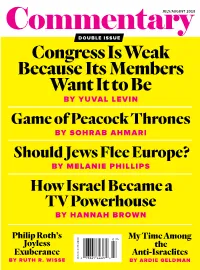

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

WHY COMPETITION in the POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA a Strategy for Reinvigorating Our Democracy

SEPTEMBER 2017 WHY COMPETITION IN THE POLITICS INDUSTRY IS FAILING AMERICA A strategy for reinvigorating our democracy Katherine M. Gehl and Michael E. Porter ABOUT THE AUTHORS Katherine M. Gehl, a business leader and former CEO with experience in government, began, in the last decade, to participate actively in politics—first in traditional partisan politics. As she deepened her understanding of how politics actually worked—and didn’t work—for the public interest, she realized that even the best candidates and elected officials were severely limited by a dysfunctional system, and that the political system was the single greatest challenge facing our country. She turned her focus to political system reform and innovation and has made this her mission. Michael E. Porter, an expert on competition and strategy in industries and nations, encountered politics in trying to advise governments and advocate sensible and proven reforms. As co-chair of the multiyear, non-partisan U.S. Competitiveness Project at Harvard Business School over the past five years, it became clear to him that the political system was actually the major constraint in America’s inability to restore economic prosperity and address many of the other problems our nation faces. Working with Katherine to understand the root causes of the failure of political competition, and what to do about it, has become an obsession. DISCLOSURE This work was funded by Harvard Business School, including the Institute for Strategy and Competitiveness and the Division of Research and Faculty Development. No external funding was received. Katherine and Michael are both involved in supporting the work they advocate in this report. -

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980

Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1980 Robert L. Richardson, Jr. A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by, Michael H. Hunt, Chair Richard Kohn Timothy McKeown Nancy Mitchell Roger Lotchin Abstract Robert L. Richardson, Jr. Neoconservatism: Origins and Evolution, 1945 – 1985 (Under the direction of Michael H. Hunt) This dissertation examines the origins and evolution of neoconservatism as a philosophical and political movement in America from 1945 to 1980. I maintain that as the exigencies and anxieties of the Cold War fostered new intellectual and professional connections between academia, government and business, three disparate intellectual currents were brought into contact: the German philosophical tradition of anti-modernism, the strategic-analytical tradition associated with the RAND Corporation, and the early Cold War anti-Communist tradition identified with figures such as Reinhold Niebuhr. Driven by similar aims and concerns, these three intellectual currents eventually coalesced into neoconservatism. As a political movement, neoconservatism sought, from the 1950s on, to re-orient American policy away from containment and coexistence and toward confrontation and rollback through activism in academia, bureaucratic and electoral politics. Although the neoconservatives were only partially successful in promoting their transformative project, their accomplishments are historically significant. More specifically, they managed to interject their views and ideas into American political and strategic thought, discredit détente and arms control, and shift U.S. foreign policy toward a more confrontational stance vis-à-vis the Soviet Union. -

A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects the Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society

The Russian Opposition: A Survey of Groups, Individuals, Strategies and Prospects The Russia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society By Julia Pettengill Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 1 First published in 2012 by The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society 8th Floor – Parker Tower, 43-49 Parker Street, London, WC2B 5PS Tel: 020 7340 4520 www.henryjacksonsociety.org © The Henry Jackson Society, 2012 All rights reserved The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and are not necessarily indicative of those of The Henry Jackson Society or its directors Designed by Genium, www.geniumcreative.com ISBN 978-1-909035-01-0 2 About The Henry Jackson Society The Henry Jackson Society: A cross-partisan, British think-tank. Our founders and supporters are united by a common interest in fostering a strong British, European and American commitment towards freedom, liberty, constitutional democracy, human rights, governmental and institutional reform and a robust foreign, security and defence policy and transatlantic alliance. The Henry Jackson Society is a company limited by guarantee registered in England and Wales under company number 07465741 and a charity registered in England and Wales under registered charity number 1140489. For more information about Henry Jackson Society activities, our research programme and public events please see www.henryjacksonsociety.org. 3 CONTENTS Foreword by Chris Bryant MP 5 About the Author 6 About the Russia Studies Centre 6 Acknowledgements 6 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8 INTRODUCTION 11 CHAPTER -

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 a Thesis Submitted to the University of Manches

Shaping the Inheritance of the Spanish Civil War on the British Left, 1939-1945 A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2017 David W. Mottram School of Arts, Languages and Cultures Table of contents Abstract p.4 Declaration p.5 Copyright statement p.5 Acknowledgements p.6 Introduction p.7 Terminology, sources and methods p.10 Structure of the thesis p.14 Chapter One The Lost War p.16 1.1 The place of ‘Spain’ in British politics p.17 1.2 Viewing ‘Spain’ through external perspectives p.21 1.3 The dispersal, 1939 p.26 Conclusion p.31 Chapter Two Adjustments to the Lost War p.33 2.1 The Communist Party and the International Brigaders: debt of honour p.34 2.2 Labour’s response: ‘The Spanish agitation had become history’ p.43 2.3 Decline in public and political discourse p.48 2.4 The political parties: three Spanish threads p.53 2.5 The personal price of the lost war p.59 Conclusion p.67 2 Chapter Three The lessons of ‘Spain’: Tom Wintringham, guerrilla fighting, and the British war effort p.69 3.1 Wintringham’s opportunity, 1937-1940 p.71 3.2 ‘The British Left’s best-known military expert’ p.75 3.3 Platform for influence p.79 3.4 Defending Britain, 1940-41 p.82 3.5 India, 1942 p.94 3.6 European liberation, 1941-1944 p.98 Conclusion p.104 Chapter Four The political and humanitarian response of Clement Attlee p.105 4.1 Attlee and policy on Spain p.107 4.2 Attlee and the Spanish Republican diaspora p.113 4.3 The signal was Greece p.119 Conclusion p.125 Conclusion p.127 Bibliography p.133 49,910 words 3 Abstract Complexities and divisions over British left-wing responses to the Spanish Civil War between 1936 and 1939 have been well-documented and much studied. -

Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 104 Rev1 Page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative Hberkc Ch5 Mp 105 Rev1 Page 105

Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_103 rev1 page 103 part iii Neoconservatism Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_104 rev1 page 104 Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_105 rev1 page 105 chapter five The Neoconservative Journey Jacob Heilbrunn The Neoconservative Conspiracy The longer the United States struggles to impose order in postwar Iraq, the harsher indictments of the George W. Bush administration’s foreign policy are becoming. “Acquiring additional burdens by engag- ing in new wars of liberation is the last thing the United States needs,” declared one Bush critic in Foreign Affairs. “The principal problem is the mistaken belief that democracy is a talisman for all the world’s ills, and that the United States has a responsibility to promote dem- ocratic government wherever in the world it is lacking.”1 Does this sound like a Democratic pundit bashing Bush for par- tisan gain? Quite the contrary. The swipe came from Dimitri Simes, president of the Nixon Center and copublisher of National Interest. Simes is not alone in calling on the administration to reclaim the party’s pre-Reagan heritage—to abandon the moralistic, Wilsonian, neoconservative dream of exporting democracy and return to a more limited and realistic foreign policy that avoids the pitfalls of Iraq. 1. Dimitri K. Simes, “America’s Imperial Dilemma,” Foreign Affairs (Novem- ber/December 2003): 97, 100. Hoover Press : Berkowitz/Conservative hberkc ch5 Mp_106 rev1 page 106 106 jacob heilbrunn In fact, critics on the Left and Right are remarkably united in their assessment of the administration. Both believe a neoconservative cabal has hijacked the administration’s foreign policy and has now overplayed its hand. -

Imagination Movers: the Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism

Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Social, Political, Ethical, and Cultural Thought Francois Debrix, Chair Matthew Gabriele Matthew Dallek James Garrison Timothy Luke February 19, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: conservatism, imagination, historicism, intellectual history counter-narrative, populism, traditionalism, paleo-conservatism Imagination Movers: The Construction of Conservative Counter-Narratives in Reaction to Consensus Liberalism Seth James Bartee ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore what exactly bound post-Second World War American conservatives together. Since modern conservatism’s recent birth in the United States in the last half century or more, many historians have claimed that both anti-communism and capitalism kept conservatives working in cooperation. My contention was that the intellectual founder of postwar conservatism, Russell Kirk, made imagination, and not anti-communism or capitalism, the thrust behind that movement in his seminal work The Conservative Mind. In The Conservative Mind, published in 1953, Russell Kirk created a conservative genealogy that began with English parliamentarian Edmund Burke. Using Burke and his dislike for the modern revolutionary spirit, Kirk uncovered a supposedly conservative seed that began in late eighteenth-century England, and traced it through various interlocutors into the United States that culminated in the writings of American expatriate poet T.S. Eliot. What Kirk really did was to create a counter-narrative to the American liberal tradition that usually began with the French Revolution and revolutionary figures such as English-American revolutionary Thomas Paine.