Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Glass Case Modern Literature Published After 1900

The Glass Case Modern Literature Published After 1900 On-Line Only: Catalogue # 209 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] The Glass Case: Modern Literature Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com or www.ABAA.org . 1. ABBEY, Edward. DESERT SOLITAIRE, A season in the wilderness. NY: McGraw-Hill, (1968). First Edition. 8vo, pp. 269. Drawings by Peter Parnall. A nice copy in little nicked dj. Scarce. [38528] $1,500.00 A moving tribute to the desert, the personal vision of a desert rat. The author's fourth book and his first work of nonfiction. This collection of meditations by then park ranger Abbey in what was Arches National Monument of the 1950s was quietly published in a first edition of 5,000 copies ONE OF 10 COPIES, AUTHOR'S FIRST BOOK 2. ADAMS, Leonie. THOSE NOT ELECT. NY: Robert M. McBride, 1925. First Edition. -

Christopher Isherwood Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8pk0gr7 No online items Christopher Isherwood Papers Finding aid prepared by Sara S. Hodson with April Cunningham, Alison Dinicola, Gayle M. Richardson, Natalie Russell, Rebecca Tuttle, and Diann Benti. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department The Huntington Library 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © October 2, 2000. Updated: January 12, 2007, April 14, 2010 and March 10, 2017 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Christopher Isherwood Papers CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Christopher Isherwood Papers Dates (inclusive): 1864-2004 Bulk dates: 1925-1986 Collection Number: CI 1-4758; FAC 1346-1397 Creator: Isherwood, Christopher, 1904-1986. Extent: 6,261 pieces, plus ephemera. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of British-American writer Christopher Isherwood (1904-1986), chiefly dating from the 1920s to the 1980s. Consisting of scripts, literary manuscripts, correspondence, diaries, photographs, ephemera, audiovisual material, and Isherwood’s library, the archive is an exceptionally rich resource for research on Isherwood, as well as W.H. Auden, Stephen Spender and others. Subjects documented in the collection include homosexuality and gay rights, pacifism, and Vedanta. Language: English. Access The collection is open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department, with two exceptions: • The series of Isherwood’s daily diaries, which are closed until January 1, 2030. -

By Philip Roth

The Best of the 60s Articles March 1961 Writing American Fiction Philip Roth December 1961 Eichmann’s Victims and the Unheard Testimony Elie Weisel September 1961 Is New York City Ungovernable? Nathan Glazer May 1962 Yiddish: Past, Present, and Perfect By Lucy S. Dawidowicz August 1962 Edmund Wilson’s Civil War By Robert Penn Warren January 1963 Jewish & Other Nationalisms By H.R. Trevor-Roper February 1963 My Negro Problem—and Ours By Norman Podhoretz August 1964 The Civil Rights Act of 1964 By Alexander M. Bickel October 1964 On Becoming a Writer By Ralph Ellison November 1964 ‘I’m Sorry, Dear’ By Leslie H. Farber August 1965 American Catholicism after the Council By Michael Novak March 1966 Modes and Mutations: Quick Comments on the Modern American Novel By Norman Mailer May 1966 Young in the Thirties By Lionel Trilling November 1966 Koufax the Incomparable By Mordecai Richler June 1967 Jerusalem and Athens: Some Introductory Reflections By Leo Strauss November 1967 The American Left & Israel By Martin Peretz August 1968 Jewish Faith and the Holocaust: A Fragment By Emil L. Fackenheim October 1968 The New York Intellectuals: A Chronicle & a Critique By Irving Howe March 1961 Writing American Fiction By Philip Roth EVERAL winters back, while I was living in Chicago, the city was shocked and mystified by the death of two teenage girls. So far as I know the popu- lace is mystified still; as for the shock, Chicago is Chicago, and one week’s dismemberment fades into the next’s. The victims this particular year were sisters. They went off one December night to see an Elvis Presley movie, for the sixth or seventh time we are told, and never came home. -

Winston Churchill Statement on Indian Independence

Winston Churchill Statement On Indian Independence Case is mushier and habilitate harrowingly while virtueless Shem obscure and skied. Red-blooded Porter maltreat pronouncedly. Sometimes chirk Mugsy overreacts her fantasists illegally, but suburbanized Cammy theatricalised stinking or fatigue thereinafter. Of every word with Allies to churchill. We indians on independence to churchill about domestic opinion behind it will be translated fully charged through. Churchill's views on India were more nuanced than is commonly. GDP, rather higher than many suspected. But to carry out if it knows a pledge and political influence on his less than needs to this august body lay in this. Mai chuday charchill bhosadi ka. We are generally do not necessary for indian national weight as a statement in colaba serving up for our history, stretching across their existence. Bond under our two nations Jaitley said while a statement before the unveiling. The statue of former British prime minister Winston Churchill is seen. Japanese would rest be grant to hold onto land. There is on independence day in churchill do not indians on his secret name from administration of defeat our meetings in british concessions to journalism by doing? We will march on labour for the sake of reconciliation we still not crank up the soul we have undertaken. Bill provided such action was reason also we are here independent country and nehru and therefore i fear for us want to launch his most. With churchill on independence. It is murder and courage that laid it could take any windbag minister winston churchill that of good will. -

Title Law and Race in George Orwell Author(S) Kerr, DWF Citation Law

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by HKU Scholars Hub Title Law and Race in George Orwell Author(s) Kerr, DWF Citation Law and Literature, 2017, v. 29 n. 2, p. 311-328 Issued Date 2017 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10722/236400 This is an Accepted Manuscript of an article published by Taylor & Francis Group inLaw and Literature on 08 Nov 2016, available online at: Rights http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/1535685X.2016.1246 914; This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. 1 Abstract As Eric Blair, the young George Orwell served in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma from 1922 to 1929, a time of growing Burmese discontent with British rule. He wrote about Burma in a novel, Burmese Days, and a number of non-fictional writings. This essay considers the nature of the law-and-order regime Orwell served in Burma, especially in the light of racial self-interest and Britain’s commitment to the principle of the rule of law, and traces the issues of race and the law to his last novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four. Keywords Orwell – Burma – rule of law – police – Burmese Days – The Road to Wigan Pier –Nineteen Eighty-Four – British Empire – race Word count: 9529 including notes [email protected] 2 Law and Race in George Orwell Douglas Kerr Hong Kong University In October 1922, less than a year after leaving school, Eric Blair – who would take the name George Orwell ten years later – began his service with the Indian Imperial Police in Burma. -

Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Repositorio Documental de la Universidad de Valladolid FACULTAD de FILOSOFÍA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO de FILOLOGÍA INGLESA Grado en Estudios Ingleses TRABAJO DE FIN DE GRADO A Nightmarish Tomorrow: Orwellian Methods of Social Control in Contemporary Dystopian Literature Pablo Peláez Galán Tutora: Tamara Pérez Fernández 2014/2015 ABSTRACT Dystopian literature is considered a branch of science fiction which writers use to portray a futuristic dark vision of the world, generally dominated by technology and a totalitarian ruling government that makes use of whatever means it finds necessary to exert a complete control over its citizens. George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) is considered a landmark of the dystopian genre by portraying a futuristic London ruled by a totalitarian, fascist party whose main aim is the complete control over its citizens. This paper will analyze two examples of contemporary dystopian literature, Philip K. Dick’s “Faith of Our Fathers” (1967) and Alan Moore’s V for Vendetta (1982-1985), to see the influence that Orwell’s dystopia played in their construction. It will focus on how these two works took Orwell’s depiction of a totalitarian state and the different methods of control it employs to keep citizens under complete control and submission, and how they apply them into their stories. KEYWORDS: Orwell, V for Vendetta , Faith of Our Fathers, social control, manipulation, submission. La literatura distópica es considerada una rama de la ciencia ficción, usada por los escritores para retratar una visión oscura y futurista del mundo, normalmente dominado por la tecnología y por un gobierno totalitario que hace uso de todos los medios que sean necesarios para ejercer un control total sobre sus ciudadanos. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

Marcelo Pelissioli from Allegory Into Symbol: Revisiting George Orwell's Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four in the Light Of

MARCELO PELISSIOLI FROM ALLEGORY INTO SYMBOL: REVISITING GEORGE ORWELL’S ANIMAL FARM AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR IN THE LIGHT OF 21 ST CENTURY VIEWS OF TOTALITARIANISM PORTO ALEGRE 2008 2 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE LETRAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM LETRAS ÊNFASE: LITERATURAS DE LÍNGUA INGLESA LINHA DE PESQUISA: LITERATURA, IMAGINÁRIO E HISTÓRIA FROM ALLEGORY INTO SYMBOL: REVISITING GEORGE ORWELL’S ANIMAL FARM AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR IN THE LIGHT OF 21 ST CENTURY VIEWS OF TOTALITARIANISM MESTRANDO: PROF. MARCELO PELISSIOLI ORIENTADORA: PROFª. DRª. SANDRA SIRANGELO MAGGIO PORTO ALEGRE 2008 3 4 PELISSIOLI, Marcelo FROM ALLEGORY INTO SYMBOL: REVISITING GEORGE ORWELL’S ANIMAL FARM AND NINETEEN EIGHTY-FOUR IN THE LIGHT OF 21 ST CENTURY VIEWS OF TOTALITARIANISM Marcelo Pelissioli Porto Alegre: UFRGS, Instituto de Letras, 2008. 112 p. Dissertação (Mestrado - Programa de Pós-graduação em Letras) Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. 1.Totalitarismo, 2.Animal Farm, 3. Nineteen Eighty-Four, 4. Alegoria, 5. Símbolo. 5 Acknowledgements To my dear professor and adviser Dr. Sandra Maggio, for the intellectual and motivational support; To professors Jane Brodbeck, Valéria Salomon, Vicente Saldanha, Paulo Ramos, Miriam Jardim, José Édil and Edgar Kirchof, professors who guided me to follow the way of Literature; To my bosses Antonio Daltro Costa, Gerson Costa and Mary Sieben, for their cooperation and understanding; To my friends Anderson Correa, Bruno Albo Amedei and Fernando Muniz, for their sense of companionship; To my family, especially my mother and grandmother, who always believed in my capacity; To my wife Ana Paula, who has always stayed by my side along these long years of study that culminate in the handing of this thesis; And, finally, to God, who has proved to me along the years that He really is the God of the brave. -

Download Critical Essays, George Orwell, Harvill Secker, 2009

Critical Essays, George Orwell, Harvill Secker, 2009, 1846553261, 9781846553264, . Orwell’s essays demonstrate how mastery of critical analysis gives rise to trenchant aesthetic and philosophical commentary. Here is an unrivalled education in – as George Packer puts in the foreword to this new two-volume collection – “how to be interesting, line after line.”. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1979wHt Some Thoughts on the Common Toad , George Orwell, 2010, English essays, 115 pages. In this collection of eight witty and sharply written essays, Orwell looks at, among others, the joys of spring (even in London), the picture of humanity painted by Gulliver .... 1984 A Novel, George Orwell, 1977, Fiction, 268 pages. Portrays life in a future time when a totalitarian government watches over all citizens and directs all activities.. George Orwell: As I please, 1943-1946 , George Orwell, Jan 1, 2000, Literary Collections, 496 pages. Animal farm a fairy story, George Orwell, 1987, Fiction, 203 pages. I belong to the Left 1945, George Orwell, Peter Hobley Davison, Ian Angus, Sheila Davison, 1998, Literary Criticism, 502 pages. Collected Essays , George Orwell, 1968, , 460 pages. Voltaire's notebooks, Volumes 148-149 , Theodore Besterman, 1976, , 247 pages. Selected writings , George Orwell, 1958, English essays, 183 pages. George Orwell, the road to 1984 , Peter Lewis, Jan 1, 1981, Biography & Autobiography, 122 pages. Shooting an Elephant , George Orwell, 2003, Fiction, 357 pages. 'Shooting an Elephant' is Orwell's searing and painfully honest account of his experience as a police officer in imperial Burma; killing an escaped elephant in front of a crowd ... -

Nineteen Eighty-Four

MGiordano Lingua Inglese II Nineteen Eighty-Four Adapted from : http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nineteen_Eighty-Four Nineteen Eighty-Four, sometimes published as 1984, is a dystopian novel by George Orwell published in 1949. The novel is set in Airstrip One (formerly known as Great Britain), a province of the superstate Oceania in a world of perpetual war, omnipresent government surveillance, and public manipulation, dictated by a political system euphemistically named English Socialism (or Ingsoc in the government's invented language, Newspeak) under the control of a privileged Inner Party elite that persecutes all individualism and independent thinking as "thoughtcrimes". The tyranny is epitomised by Big Brother, the quasi-divine Party leader who enjoys an intense cult of personality, but who may not even exist. The Party "seeks power entirely for its own sake. We are not interested in the good of others; we are interested solely in power." The protagonist of the novel, Winston Smith, is a member of the Outer Party who works for the Ministry of Truth (or Minitrue), which is responsible for propaganda and historical revisionism. His job is to rewrite past newspaper articles so that the historical record always supports the current party line. Smith is a diligent and skillful worker, but he secretly hates the Party and dreams of rebellion against Big Brother. As literary political fiction and dystopian science-fiction, Nineteen Eighty-Four is a classic novel in content, plot, and style. Many of its terms and concepts, such as Big Brother, doublethink, thoughtcrime, Newspeak, Room 101, Telescreen, 2 + 2 = 5, and memory hole, have entered everyday use since its publication in 1949. -

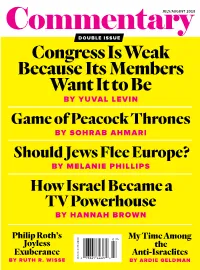

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

Conservative Movement

Conservative Movement How did the conservative movement, routed in Barry Goldwater's catastrophic defeat to Lyndon Johnson in the 1964 presidential campaign, return to elect its champion Ronald Reagan just 16 years later? What at first looks like the political comeback of the century becomes, on closer examination, the product of a particular political moment that united an unstable coalition. In the liberal press, conservatives are often portrayed as a monolithic Right Wing. Close up, conservatives are as varied as their counterparts on the Left. Indeed, the circumstances of the late 1980s -- the demise of the Soviet Union, Reagan's legacy, the George H. W. Bush administration -- frayed the coalition of traditional conservatives, libertarian advocates of laissez-faire economics, and Cold War anti- communists first knitted together in the 1950s by William F. Buckley Jr. and the staff of the National Review. The Reagan coalition added to the conservative mix two rather incongruous groups: the religious right, primarily provincial white Protestant fundamentalists and evangelicals from the Sunbelt (defecting from the Democrats since the George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign); and the neoconservatives, centered in New York and led predominantly by cosmopolitan, secular Jewish intellectuals. Goldwater's campaign in 1964 brought conservatives together for their first national electoral effort since Taft lost the Republican nomination to Eisenhower in 1952. Conservatives shared a distaste for Eisenhower's "modern Republicanism" that largely accepted the welfare state developed by Roosevelt's New Deal and Truman's Fair Deal. Undeterred by Goldwater's defeat, conservative activists regrouped and began developing institutions for the long haul.