“The Intellectual,” Vaclav Havel Has Written

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

6-908 Intellectual Property Policy

Policy Number: 6-908 Policy Name: Intellectual Property Policy Policy Revision Dates: 9/2018, 9/17, 8/10, 3/01, 6/99, 5/96, Page 1 2/88, 9/87, 9/85 6-908 Intellectual Property Policy The Arizona Board of Regents and the three universities that the board governs, are all dedicated to teaching, research, and the extension of knowledge to the public. The university community recognizes its responsibility to produce and disseminate knowledge. Inherent in this responsibility is the need to encourage the production of Scholarly Works and the development of Intellectual Property (IP), some of which may have potential commercial value. These activities contribute to the professional development of the individuals involved, enhance the reputation of the university in which they work, provide additional educational opportunities for participating students, and promote the public welfare. Board-Owned IP should be appropriately managed in the best interest of the state and the university system. This policy addresses ownership rights and revenue sharing for Board-Owned IP. Compliance with this policy is required for all employees as part of the terms of their employment. This policy also applies to non-employee students of the university and to anyone else who creates intellectual property with significant use of board or university resources. University-wide trademarks, logos, and other board or university indicia or identifiers are not subject to or covered by this policy. Definitions of capitalized terms are included in the final section of this policy. A. Ownership of Intellectual Property. 1. Board-Owned IP: a. The board owns all intellectual property in each of the following categories: (1) Any intellectual property created by an employee in the course and scope of employment; and (2) Any intellectual property created with the significant use of board or university resources. -

Poverty and Human Rights Thomas Pogge Human Rights Would Be Fully Realized, If All Human Beings Had Secure Access to the Objects of These Rights

Poverty and Human Rights Thomas Pogge Human rights would be fully realized, if all human beings had secure access to the objects of these rights. Our world is today very far from this ideal. Piecing together the current global record, we find that most of the current massive underfulfillment of human rights is more or less directly connected to poverty. The connection is direct in the case of basic social and economic human rights, such as the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of oneself and one’s family, including food, clothing, housing, and medical care. The connection is more indirect in the case of civil and political human rights associated with democratic government and the rule of law. Desperately poor people, often stunted, illiterate, and heavily preoccupied with the struggle to survive, typically lack effective means for resisting or rewarding their rulers, who are therefore likely to rule them oppressively while catering to the interests of other, often foreign, agents (governments and corporations, for instance) who are more capable of reciprocation. The statistics are appalling. Out of a total of 6575 million human beings, 830 million are reportedly chronically undernourished, 1100 million lack access to safe water and 2600 million lack access to basic sanitation (UNDP 2006: 174, 33). About 2000 million lack access to essential drugs (www.fic.nih.gov/about/summary.html). Some 1000 million have no adequate shelter and 2000 million lack electricity (UNDP 1998: 49). Some 799 million adults are illiterate (www.uis.unesco.org). Some 250 million children between 5 and 14 do wage work outside their household with 170.5 million of them involved in hazardous work and 8.4 million in the “unconditionally worst” forms of child labor, which involve slavery, forced or bonded labor, forced recruitment for use in armed conflict, forced prostitution or pornography, or the production or trafficking of illegal drugs (ILO 2002: 9, 11, 17, 18). -

Lumpenproletariat, N. : Oxford English Dictionary 21/12/14 1:12 PM

lumpenproletariat, n. : Oxford English Dictionary 21/12/14 1:12 PM Oxford English Dictionary | The definitive record of the English language lumpenproletariat, n. Pronunciation: /!l"mp#npr#$l%&t'#r%#t/ Etymology: < German lumpenproletariat (K. Marx 1850, in Die Klassenkämpfe in Frankreich and 1852, in Der achtzehnte Brumaire des Louis Bonaparte), < lumpen , rag (lump ragamuffin: see LUMP n.1) + proletariat (see PROLETARIAT n.). A term applied, orig. by Karl Marx, to the lowest and most degraded section of the proletariat; the ‘down and outs’ who make no contribution to the workers' cause. 1924 H. KUHN tr. Marx Class Struggles France I. 38 The financial aristocracy, in its methods of acquisition as well as in its enjoyments, is nothing but the reborn Lumpenproletariat, the rabble on the heights of bourgeois society. 1942 New Statesman 17 Oct. 255/1 He [sc. Hitler] mixed with the Lumpen-proletariat, the nomadic outcasts in the no-man's-land of society. 1971 ‘P. KAVANAGH’ Triumph of Evil (1972) ii. 19 The rightist reaction of the white lumpenproletariat is easily imagined. Their instinctive response is racist and anti-intellectual. DERIVATIVES !lumpen adj. boorish, stupid, unenlightened, used derisively to describe persons, attitudes, etc., supposed to be characteristic of the lumpenproletariat; also ellipt. or as n. 1944 A. KOESTLER in Horizon Mar. 167 Thus the intelligentsia..becomes the Lumpen-Bourgeoisie in the age of its decay. 1948 J. STEINBECK Russ. Jrnl. (1949) ix. 220 This journal will not be satisfactory either to the ecclesiastical Left, nor the lumpen Right. 1949 A. WILSON Wrong Set 57 Like called to like. -

The Public Intellectual in Critical Marxism: from the Organic Intellectual to the General Intellect Papel Político, Vol

Papel Político ISSN: 0122-4409 [email protected] Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Colombia Herrera-Zgaib, Miguel Ángel The public intellectual in Critical Marxism: From the Organic Intellectual to the General Intellect Papel Político, vol. 14, núm. 1, enero-junio, 2009, pp. 143-164 Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Bogotá, Colombia Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=77720764007 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative The Public Intellectual in Critical Marxism: From the Organic Intellectual to the General Intellect* El intelectual público en el marxismo crítico: del intelectual orgánico al intelecto general Miguel Ángel Herrera-Zgaib** Recibido: 28/02/09 Aprobado evaluador interno: 31/03/09 Aprobado evaluador externo: 24/03/09 Abstract Resumen The key issue of this essay is to look at Antonio El asunto clave de este artículo es examinar los Gramsci’s writings as centered on the theme escritos de Antonio Gramsci como centrados en of public intellectual within the Communist el tema del intelectual público, de acuerdo con la experience in the years 1920s and 1930s. The experiencia comunista de los años 20 y 30 del si- essay also deals with the present significance of glo XX. El artículo también trata la significación what Gramsci said about the organic intellectual presente de aquello que Gramsci dijo acerca del regarding the existence of the general intellect intelectual orgánico, considerando la existencia in the current capitalist relations of production del intelecto general en las presentes relaciones de and reproduction of society. -

9 Why Is There Learning Disabilities? Be Like

Why Is There Learning Disabilities? that their use enables children to be taught better. After all, many of these categories were discovered and researched by 'experts', so they must have validity. But in accepting commonly-used categories for children, we also tacitly accept an ideology about what schools are for, what society should be like, and what the 'normal' person should 9 Why Is There Learning Disabilities? be like. Far from being objective fact, ideology rests on values and A Critical Analysis ofthe Birth ofthe assumptions that cannot be proven, and that serve some people better than others. Field in Its Social Context This chapter illustrates the hidden ideology in 'scientific' cate gories and resulting school structures, by examining one category: learning disabilities. The chapter will show that, while discussions Christine E. Sleeter surrounding the emergence and subsequent use of the category were ostensibly about similarities in a certain identifiable group of chil dren, the category developed largely on the basis of an ideology regarding the 'good' US economic order, the 'proper' social function of schooling, and the 'good' culture. Learning disabilities is the newest special education category in Abstract the US, having achieved national status as a field in 1963 when the Association for Children with Learning Disabilities was founded. In This chapter presents an interpretation of why the category of 1979, learning disabilities overtook speech impairment as the largest learning disabilities emerged, that differs from interpretations special education category. By 1982, 41 per cent of the students in that currently prevail. It argues that the category was created special education in US schools were categorized as learning disabled; in response to social conditions during the late 1950s and they constituted 4.4 per cent of all students enrolled in the public early 1960s which brought about changes in schools that were schools (Plisko, 1984). -

Ego Identity Status, Intellectual Development, and Academic Achievement in University of Freshman

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Master's Theses 1996 Ego Identity Status, Intellectual Development, and Academic Achievement in University of Freshman Deborah E. Flammia University of Rhode Island Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses Recommended Citation Flammia, Deborah E., "Ego Identity Status, Intellectual Development, and Academic Achievement in University of Freshman" (1996). Open Access Master's Theses. Paper 1656. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/theses/1656 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. B F7J.'1 -~ T3 F 53(p 19 9/p EGO IDENTITY STATUS, INTELLECTUAL DEVELOPMENT, AND ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT IN UNIVERSITY FRESHMAN BY DEBORAH E. FLAMMIA A MASTERS THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN PSYCHOLOGY 3s-q (pL.froo UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND 1996 Abstract Late adolescent development was examined through the attitudes , values , beliefs, and academic performance of 121 Freshman students , 57 male and 64 female , at the University of Rhode Island. Marcia's (1966) operationalization of Erik Erikson's psycho-social theory of late adolescence and William Perry's (1970) model of intellectual formation in the college years were instrumentally applied through two objective tests that classify students into the stages of each theory. Findings confirm the study's hypothesis of a significant relationship between academic achievemen t and identity status. There were significant main effects of identity status , as reported in GPA scores , before and after intelligence (SAT scores) was controlled . -

SOCIAL STRATIFICATION and POLITICAL Behavrori an EMPHASIS \T,PON STRUCTURAL 11YNAMICS

SOCIAL STRATIFICATION AND POLITICAL BEHAVrORI AN EMPHASIS \T,PON STRUCTURAL 11YNAMICS by Christopher Bates Doob A.B., Oberlin College, 1962 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Oberlin College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Sociology 1964 ~-,-\t ii I," - ~ <" . , Preface There are a number of people whose assistance has made this project possible. Without their aid I literally would have been unable to complete this thesis and obtain my degree. xy" profoundest acknowledgment goes to Dr. Kiyoshi Ikeda, whose knowledge of theory and methodology literally shaped this project. The influence of Professors Richard R. xy"ers, George E. Simpson, .J. Milton Yinger, and Donald P. Warwick is also evident at various points through- out this work. Mr. Thomas Bauer, Dr. Leonard Doob, Miss Nancy Durham, and Miss .June Wright have given valuable assistance at different stages of the process. Christopher B. Doob Oberlin College June 1964 09\,~O\A4 'i::l "\ ~ S iii Table of Contents Page Preface 11 r. Introduction The Problem 1 An Historical Approach to the Dynamics of Social Stratification 2 Broad Sociological Propositions Concerning Social Mobility 3 Empirical Studies 4 Status Crystallization 6 Static Structural Variables in This Study 7 Some Observations on Voting Behavior 11 The Hypotheses 12 II. Methodology The Sample 17 The Major Independent Variables 18 Intermediate Variables 25 The Dependent Variables 26 A Concluding Note 28 III. Description of the Findings The Relationship of Mobility, Class, and Intermediate Variables to Liberalism-Conservatism 30 The Intermediate Variables 31 Status Crystallization, Class, and Liberalism Conservatism • iv III. -

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - the American Interest

Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy - The American Interest https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-... https://www.the-american-interest.com/2019/04/03/nathan-glazer-merit-before-meritocracy/ WHAT ONCE WAS Nathan Glazer—Merit Before Meritocracy PETER SKERRY The perambulating path of this son of humble Jewish immigrants into America’s intellectual and political elites points to how much we have overcome—and lost—over the past century. The death of Nathan Glazer in January, a month before his 96th birthday, has been rightly noted as the end of an era in American political and intellectual life. Nat Glazer was the last exemplar of what historian Christopher Lasch would refer to as a “social type”: the New York intellectuals, the sons and daughters of impoverished, almost exclusively Jewish immigrants who took advantage of the city’s public education system and then thrived in the cultural and political ferment that from the 1930’s into the 1960’s made New York the leading metropolis of the free world. As Glazer once noted, the Marxist polemics that he and his fellow students at City College engaged in afforded them unique insights into, and unanticipated opportunities to interpret, Soviet communism to the rest of America during the Cold War. Over time, postwar economic growth and political change resulted in the relative decline of New York and the emergence of Washington as the center of power and even glamor in American life. Nevertheless, Glazer and his fellow New York intellectuals, relocated either to major universities around the country or to Washington think tanks, continued to exert remarkable influence over both domestic and foreign affairs. -

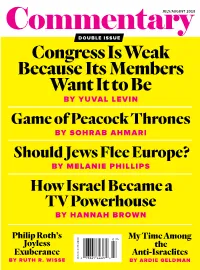

Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be

CommentaryJULY/AUGUST 2018 DOUBLE ISSUE Congress Is Weak Because Its Members Want It to Be BY YUVAL LEVIN Game of Peacock Thrones BY SOHRAB AHMARI Should Jews Flee Europe? BY MELANIE PHILLIPS Commentary How Israel Became a JULY/AUGUST 2018 : VOLUME 146 NUMBER 1 146 : VOLUME 2018 JULY/AUGUST TV Powerhouse BY HANNAH BROWN Philip Roth’s My Time Among Joyless the Exuberance Anti-Israelites BY RUTH R. WISSE CANADA $7.00 : US $5.95 BY ARDIE GELDMAN We join in celebrating Israel’s 70 years. And Magen David Adom is proud to have saved lives for every one of them. Magen David Adom, Israel’s largest and premier emergency medical response agency, has been saving lives since before 1948. Supporters like you provide MDA’s 27,000 paramedics, EMTs, and civilian Life Guardians — more than 90% of them volunteers — with the training, equipment, and rescue vehicles they need. In honor of Israel’s 70th anniversary, MDA has launched a 70 for 70 Campaign that will put 70 new ambulances on the streets of Israel this year. There is no better way to celebrate this great occasion and ensure the vitality of the state continues for many more years. Please give today. 352 Seventh Avenue, Suite 400 New York, NY 10001 Toll-Free 866.632.2763 • [email protected] www.afmda.org Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by helping put 70 new ambulances on its streets. FOR SEVENTY Celebrate Israel’s 70th anniversary by putting 70 new ambulances on its streets. please join us for the ninth annual COMMENTARY ROAST this year’s victim: JOE LIEBERMAN monday, october 8, 2018, new york city CO-CHAIR TABLES: $25,000. -

Situational Stratification: a Micro-Macro Theory of Inequality Author(S): Randall Collins Source: Sociological Theory, Vol. 18, No

Situational Stratification: A Micro-Macro Theory of Inequality Author(s): Randall Collins Source: Sociological Theory, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Mar., 2000), pp. 17-43 Published by: American Sociological Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/223280 Accessed: 05/05/2009 09:51 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=asa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Sociological Theory. http://www.jstor.org Situational Stratification: A Micro-Macro Theory of Inequality RANDALL COLLINS University of Pennsylvania Are received sociological theories capable of grasping the realities of contemporary strat- ification? We think in terms of a structured hierarchy of inequality. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE a Study of the Friendship Quality in Adolescents with and Without an Intellectual Disability

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE A Study of the Friendship Quality in Adolescents With and Without an Intellectual Disability A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Education by Leigh Ann Tipton June 2011 Thesis Committee: Dr. Jan Blacher, Chairperson Dr. Mike Vanderwood Dr. Sara Castro-Olivo Copyright by Leigh Ann Tipton 2011 The Thesis of Leigh Ann Tipton is approved: _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ _________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS A study of the Friendship Quality in Adolescents With and Without an Intellectual Disability by Leigh Ann Tipton Master of Arts, Graduate Program in Education University of California, Riverside, June 2011 Dr. Jan Blacher, Chairpoerson High friendship quality is comprised of both positive and negative features in which a friendship should have high levels of intimacy, companionship and closeness and low levels of conflict. Quality of friendship research was examined in adolescents with or without intellectual disabilities (ID) to understand not only the differences but also the predictors of successful peer relationships. The differences between parent and adolescent views of friendship were also considered. Participants were 106, 13-year old adolescents with (N=78) or without intellectual disabilities (N=28). Results demonstrated significant differences between both adolescent and -

The Effects of Group Status on Intragroup Behavior

The Effects of Group Status on Intragroup Behavior: Implications for Group Process and Outcome Jin Wook Chang Organizational Behavior and Theory Tepper School of Business Carnegie Mellon University Dissertation Committee: Rosalind M. Chow (Co-Chair) Anita W. Woolley (Co-Chair) Linda Argote John M. Levine The Effects of Group Status on Intragroup Behavior: Implications for Group Process and Outcome ABSTRACT How does the status of a group influence the behavior of individuals within the group? This dissertation aims to answer this question by investigating the psychological and behavioral implications of membership in high- versus low-status groups, with a primary focus on the impact of membership in a high-status group. I propose that in high-status groups, personal interests, including material and relational, are more salient, therefore guiding member behavior within the groups. This emphasis on personal gain leads to behavior that best suits their interests regardless of the impact on group outcomes. In six studies, using both experimental and correlational methods, I test this main idea and examine boundary conditions. The first set of studies examines members’ group-oriented behavior, and finds that membership in a high-status group (a) decreases the resources allocated for the group as members attempt to ensure personal gain; (b) lowers the preference for a competent newcomer who may enhance group outcome but who may jeopardize personal gains; and (c) reduces the amount of voluntary information sharing during group negotiations, hindering group outcomes. The findings also reveal that reducing the conflict between group and personal interests via cooperative incentives encourages group- oriented behavior in high-status groups.