New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

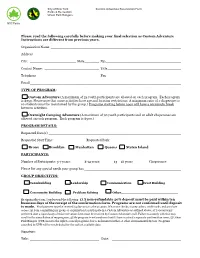

Please Read the Following Carefully Before Making Your Final Selection As Custom Adventure Instructions Are Different from Previous Years

City of New York Custom Adventure Reservation Form Parks & Recreation Urban Park Rangers Please read the following carefully before making your final selection as Custom Adventure Instructions are different from previous years. Organization Name ______________________________________________________________ Address ______________________________________________________________________ City: ______________________ State _______ Zip ____________________________________ Contact Name: __________________________ Title ___________________________________ Telephone ______________________________ Fax ___________________________________ Email ________________________________________________________________________ TYPE OF PROGRAM: Custom Adventure (A maximum of 32 youth participants are allowed on each program. Each program is $250. Please note that some activities have age and location restrictions. A minimum ratio of 1 chaperone to 10 students must be maintained by the group.) Programs starting before noon will have a 60 minute break between activities. Overnight Camping Adventure (A maximum of 30 youth participants and 10 adult chaperones are allowed on each program. Each program is $500.) PROGRAM DETAILS: Requested Date(s) _______________________________________________________________ Requested Start Time: _______________ Requested Park: _________________________________ Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens Staten Island PARTICIPANTS: Number of Participants: 3-7 years: _____ 8-12 years: _____ 13 – 18 years ______ Chaperones: ______ Please list -

Department of Parks Borough 0. Queens

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH 0. QUEENS CITY OF NEW YORK FOR THE YEARS 1927 AND 1928 JAMES BUTLER Comnzissioner of Parks Printed by I?. IIUBNEH& CO. N. Y. C. PARK BOARD WALTER I<. HERRICK, Presiden,t JAMES P. BROWNE JAMES BUTLER JOSEPH P. HENNESSEY JOHN J. O'ROURKE WILLISHOLLY, Secretary JULI~SBURGEVIN, Landscafe Architect DEPARTMENT OF PARKS Borough of Queens JAMES BUTLER, Commissioner JOSEPH F. MAFERA, Secretary WILLIA&l M. BLAKE, Superintendent ANTHONY V. GRANDE, Asst. Landscape Architect EDWARD P. KING, Assistant Engineer 1,OUIS THIESEN, Forester j.AMES PASTA, Chief Clerk CITY OF NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGHOFQUEENS March 15, 1929. Won. JAMES J. WALKER, Mayor, City of New York, City Hall, New York. Sir-In accordance with Section 1544 of the Greater New York Charter, I herewith present the Annual Report of the Department of Parks, Borough of Queens, for the two years beginning January lst, 1927, and ending December 31st, 1928. Respectfully yours, JAMES BUTLER, Commissioner. CONTENTS Page Foreword ..................................................... 7 Engineering Section ........................................... 18 Landscape Architecture Section ................................. 38 Maintenance Section ........................................... 46 Arboricultural Section ........................................ 78 Recreational Features ......................................... 80 Receipts ...................................................... 81 Budget Appropriation ....................................... -

NYMTC Regional Freight Plan

3-1 CHAPTER 3: THE THE TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM Photo Source: NYMTC Photo Source: 5. Implementation Guidance 3. Identifying & Assessing Needs 4. Improvements & Solutions 1. Regional Freight Plan Purpose & Desired Freight Outcomes 2. Freight System & Market Overview Regional Freight Plan 2018-2045 Appendix 8 | Regional Freight Plan 2018-2045 Table of Contents 1.0 Regional Freight Plan Purpose and Desired Freight Outcomes ................................................... 1-1 1.1 Plan 2045 Shared Goals and Desired Freight Outcomes ......................................................... 1-2 1.2 Institutional Context ................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Regional Context ....................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Required Federal Performance Measures................................................................................. 1-4 2.0 Freight System and Market Overview .............................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Freight System Description and Operating Characteristics ....................................................... 2-1 2.1.1 Roadway Network ......................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1.2 Rail Network .................................................................................................................. 2-8 2.1.3 Waterborne Network -

New York City, NY

REACHING FOR ZERO: The Citizens Plan for Zero Waste in New York City A “Working Document” 1st Version By Resa Dimino and Barbara Warren New York City Zero Waste Campaign and Consumer Policy Institute / Consumers Union June 2004 Consumer Policy Institute New York City Zero Waste Campaign Consumers Union c/o NY Lawyers for the Public Interest 101 Truman Ave. 151 West 30th Street, 11th Floor Yonkers, NY 10703-1057 New York, New York 10001 914-378-2455 212-244-4664 The New York City Zero Waste Campaign was first conceived at the 2nd National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit in October of 2002, where City activists were confronted with the ongoing concerns of other Environmental Justice communities that would continue to be burdened with the high volume of waste being exported from NYC. As a result of discussion with various activists in the City and elsewhere, a diverse group of environmental, social justice and neighborhood organizations came together to begin the process of planning for Zero Waste in NYC. A series of principles were initially drafted to serve as a basis for the entire plan. It is the Campaign’s intent to expand discussions about the Zero Waste goal and to gain broad support for the detailed plan. The Consumer Policy Institute is a division of Consumers Union, publisher of Consumer Reports magazine. The Institute was established to do research and education on environmental quality, public health and economic justice and other issues of concern to consumers. The Consumer Policy Institute is funded by foundation grants, government contracts, individual donations, and by Consumers Union. -

City of New York 2012-2013 Districting Commission

SUBMISSION UNDER SECTION 5 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT (42 U.S.C. § 1973c) CITY OF NEW YORK 2012-2013 DISTRICTING COMMISSION Submission for Preclearance of the Final Districting Plan for the Council of the City of New York Plan Adopted by the Commission: February 6, 2013 Plan Filed with the City Clerk: March 4, 2013 Dated: March 22, 2013 EXPEDITED PRECLEARANCE REQUESTED TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 1 II. EXPEDITED CONSIDERATION (28 C.F.R. § 51.34) ................................................. 3 III. THE NEW YORK CITY COUNCIL.............................................................................. 4 IV. THE NEW YORK CITY DISTRICTING COMMISSION ......................................... 4 A. Districting Commission Members ....................................................................... 4 B. Commissioner Training ........................................................................................ 5 C. Public Meetings ..................................................................................................... 6 V. DISTRICTING PROCESS PER CITY CHARTER ..................................................... 7 A. Schedule ................................................................................................................. 7 B. Criteria .................................................................................................................. -

Bronx Civic Center

Prepared for New York State BRONX CIVIC CENTER Downtown Revitalization Initiative Downtown Revitalization Initiative New York City Strategic Investment Plan March 2018 BRONX CIVIC CENTER LOCAL PLANNING COMMITTEE Co-Chairs Hon. Ruben Diaz Jr., Bronx Borough President Marlene Cintron, Bronx Overall Economic Development Corporation Daniel Barber, NYCHA Citywide Council of Presidents Michael Brady, Third Avenue BID Steven Brown, SoBRO Jessica Clemente, Nos Quedamos Michelle Daniels, The Bronx Rox Dr. David Goméz, Hostos Community College Shantel Jackson, Concourse Village Resident Leader Cedric Loftin, Bronx Community Board 1 Nick Lugo, NYC Hispanic Chamber of Commerce Milton Nuñez, NYC Health + Hospitals/Lincoln Paul Philps, Bronx Community Board 4 Klaudio Rodriguez, Bronx Museum of the Arts Rosalba Rolón, Pregones Theater/Puerto Rican Traveling Theater Pierina Ana Sanchez, Regional Plan Association Dr. Vinton Thompson, Metropolitan College of New York Eileen Torres, BronxWorks Bronx Borough President’s Office Team James Rausse, AICP, Director of Planning and Development Jessica Cruz, Lead Planner Raymond Sanchez, Counsel & Senior Policy Manager (former) Dirk McCall, Director of External Affairs This document was developed by the Bronx Civic Center Local Planning Committee as part of the Downtown Revitalization Initiative and was supported by the NYS Department of State, NYS Homes and Community Renewal, and Empire State Development. The document was prepared by a Consulting Team led by HR&A Advisors and supported by Beyer Blinder Belle, -

Bronx, NY Available for Lease

RETAIL Gateway Center at Bronx Terminal Market 81,300 SF Bronx, NY Available for Lease AVAILABLE Size Available Comments Demographics 81,300 SF • 900,000 sf Regional Shopping Center 2017 Estimates • Direct access from Exit 4, 5 and 6 from the Co-Tenants Major Deegan Expressway. It is in walking 1 Mile 2 Miles 3 Miles BJ’s Wholesale Club, The Home Depot, Target, distance to 3 different subway stops Population 208,416 748,325 1,247,070 Bed, Bath & Beyond, Best Buy, Marshalls, • The nearby bridges to Upper Manhattan are Raymour & Flanigan, Burlington Coat Factory, Toll Free Michael’s, Chuck E. Cheese’s, Game Stop, • This Center is located ½ mile from Yankee Households 81,765 272,854 462,592 GNC, Applebee’s Stadium • 2,600 parking spaces in a 6-level parking Median $38,578 $38,833 $46,396 structure, flanked by two retail building Household Income structures Daytime 52,526 198,478 340,726 Population Contact our exclusive agents: Brian Schuster Peter Ripka [email protected] [email protected] 516.933.8880 212.750.6565 HARLEM RIVER Retail B – Level 2 RETAIL B/LEVEL 2 Bronx, NY 1 Corresponds with Exterior Flyer Aerial 145TH ST BRIDGE (TOLL FREE) MILL POND PARK TENNIS CENTER N E 150TH ST 87 MAJOR DEEGAN EXPY 87 MAJOR DEEGAN EXPY EXTERIOR ST (BELOW) Property Line EXTERIOR ST TO MANHATTAN SOUTH SIGN 1 RETAIL B - LEVEL 2 RETAIL P FREIGHT NORTH SIGN AREA (next page for plan with dimensions) PARKING (BELOW) BRIDGE RETAIL B PARKING RETAIL E ROOF BRIDGE (BELOW) LEVEL 2 RIVER AVE PROPOSED TENANT RETAIL UNIT B2.1 FREIGHT TOYS81,300 “R” US / BABIES SF “R” US (BELOW) 76,421 sf AREA Survey Area: 77,938 sf GARAGE – LEVEL 4 404 SPACES RETAIL A ROOF LEVEL 2 RETAIL UNIT B2.2 CHUCK E. -

2018 AIA Fellowship

This cover section is produced by the AIA Archives to show information from the online submission form. It is not part of the pdf submission upload. 2018 AIA Fellowship Nominee Brian Shea Organization Cooper Robertson Location Portland, OR Chapter AIA New York State; AIA New York Chapter Category of Nomination Category One - Urban Design Summary Statement Brian Shea has advanced the art and practice of urban design. His approach combines a rigorous method of physical analysis with creative design solutions to guide the responsible growth of American cities, communities, and campuses. Education 1976-1978, Columbia University, Master of Science in Architecture and Urban Design / 1972-1974, University of Notre Dame, Bachelor of Architecture / 1969-1972, University of Notre Dame, Bachelor of Arts Licensed in: NY Employment 1979 - present, Cooper Robertson / 1978 - 1979, Mayor's Office of Midtown Planning and Development / 1971, 1972, Boston Redevelopment Authority October 13, 2017 Karen Nichols, FAIA Fellowship Jury Chair The American Institute of Architects 1735 New York Ave NW Washington. DC 20006-5292 Dear Karen, It is a “Rare Privilege and a High Honor” to sponsor Brian Shea for elevation to the College of Fellows of the American Institute of Architects. To keep it simple, let me say that Brian is the single, finest professional I have ever known. Our relationship goes back to 1978 when he became a student of mine at the Columbia University Graduate School of Architecture. He then worked at the New York City Office of Midtown Development, and when I started Cooper Robertson in 1979, Brian became the office’s first employee. -

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

Bronx River. Holiday, the Draw Need Not Open from (A) the Draw of the Bruckner Boule- 9:15 A.M

Coast Guard, DHS § 117.771 (4) The owners of the bridge shall (b) From 11 p.m. on December 24 provide and keep in good legible condi- until 11 p.m. on December 25, the draw tion, two clearance gauges, with fig- need open only if at least two hours no- ures not less than eight inches high, tice is given. designed, installed, and maintained ac- [USCG–2007–0026, 73 FR 5749, Jan. 31, 2008] cording to the provisions of § 118.160 of this chapter. § 117.758 Tuckahoe River. (b) The draw of the Monmouth Coun- The draw of the State highway ty highway bridge, mile 4.0, at Sea bridge, mile 8.0 at Tuckahoe, shall open Bright, shall open on signal; except on signal if at least 24 hours notice is that, from May 15 through September given. 30, on Saturdays, Sundays, and holi- days, from 9 a.m. to 7 p.m., the draw [CGD82–025, 49 FR 17452, Apr. 24, 1984. Redes- ignated by CGD05–06–045, 71 FR 59383, Oct. 10, need open only on the hour and half 2006] hour. The draw need not be opened at any time for a sailboat, unless it is § 117.759 Wading River. under auxiliary power or is towed by a The draw of the Burlington County powered vessel. The owners of the highway bridge, mile 5.0 at Wading bridge shall keep in good legible condi- River, shall open on signal if at least 24 tion two clearance gages, with figures hours notice is given. not less than eight inches high, de- signed, installed and maintained ac- § 117.761 Woodbridge Creek. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens

CONGRATULATIONS OCTOBER 2018 CAPACITY FUND GRANTEES BRONX Concrete Friends – Concrete Plant Park Friends of Pelham Parkway Jackson Forest Community Garden Jardín de las Rosas Morrisania Band Project – Reverend Lena Irons Unity Park Rainbow Garden of Life and Health – Rainbow Garden Stewards of Upper Brust Park – Brust Park Survivor I Am – Bufano Park Teddy Bear Project – Street Trees, West Farms/Crotona Woodlawn Heights Taxpayers Association – Van Cortlandt Park BROOKLYN 57 Old Timers, Inc. – Jesse Owens Playground Creating Legacies – Umma Park Imani II Community Garden NYSoM Group – Martinez Playground Prephoopers Events – Bildersee Playground MANHATTAN The Dog Run at St. Nicholas Park Friends of St. Nicholas Park (FOSNP) Friends of Verdi Square Muslim Volunteers for New York – Ruppert Park NWALI - No Women Are Least International – Thomas Jefferson Park Regiven Environmental Project – St. Nicholas Park Sage’s Garden QUEENS Bay 84th Street Community Garden Elmhurst Supporters for Parks – Moore Homestead Playground Forest Park Barking Lot Friends of Alley Pond Park Masai Basketball – Laurelton Playground Roy Wilkins Pickleball Club – Roy Wilkins Recreation Center STATEN ISLAND Eibs Pond Education Program, Inc. (Friends of) – Eibs Pond Park Friends of Mariners Harbor Parks – The Big Park Labyrinth Arts Collective, Inc. – Faber Pool and Park PS 57 – Street Trees, Park Hill CITYWIDE Historic House Trust of New York City Generous private support is provided by the Altman Foundation and the MJS Foundation. Public support is provided by the NYC Council under the leadership of Speaker Corey Johnson through the Parks Equity Initiative. .