Reading the Landscape: Citywide Social Assessment of New York City Parks and Natural Areas in 2013-2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New York City Department of Parks & Recreation's Urban Park Rangers

New York City Department of Parks & Recreation’s Urban Park Rangers Calendar of Programs SATURDAY, NOVEMBER 6 S.I. Mammals: Our Furry Friends / High Rock Park 11 a.m. / High Rock Ranger Station BX Van Cortlandt on the Rocks / Van Cortlandt Park 1 p.m. / Van Cortlandt Nature Center Come on a walk, learn about the species of mammals that live in the park, and Step back in time and envision the Bronx, and the rest of the City, as it was meet our resident rabbits! millions of years ago. SUNDAY, DECEMBER 12 BX NASCAR in the Bronx / Crotona Park 1 p.m. / Crotona Nature Center Make a boxcar and race. To register: Call 311 on October 23 and ask for the BX Blowing in the Wind / Pelham Bay Park 1 p.m. / Meet at the Orchard Beach Urban Park Rangers. Nature Center Be sure to bundle up for a hike with the Rangers along the rocky coast of Orchard BK Mid-Fall Bird Walk / Marine Park 8 a.m. / Salt Marsh Nature Center Join the Urban Park Rangers for the 2nd Annual “Marsh Count” Beach. Camping 101 / Marine Park 1 p.m. / Salt Marsh Nature Center M ElectionFest / Riverside Park 1 p.m. / 72nd St. and Riverside Dr. BK Set off on your own campaign trail as we traverse almost the entirety of Riverside Come join the Urban Park Rangers as they discuss camping basics and help you Park while exploring New York’s political past, from Roosevelt in the south to plan your spring trip. Grant in the north. -

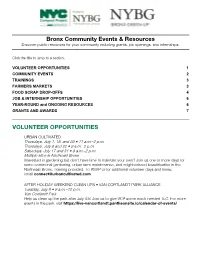

July 2021 Resources

Bronx Community Events & Resources Discover public resources for your community including grants, job openings, and internships. Click the title to jump to a section. VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES 1 COMMUNITY EVENTS 2 TRAININGS 3 FARMERS MARKETS 3 FOOD SCRAP DROP-OFFS 4 JOB & INTERNSHIP OPPORTUNITIES 6 YEAR-ROUND and ONGOING RESOURCES 6 GRANTS AND AWARDS 7 VOLUNTEER OPPORTUNITIES URBAN CULTIVATED Thursdays, July 1, 15, and 29 • 11 a.m.–2 p.m. Thursdays, July 8 and 22 • 9 a.m.–2 p.m. Saturdays, July 17 and 31 • 9 a.m.–2 p.m. Multiple sites in Northeast Bronx Interested in gardening but don’t have time to maintain your own? Join us one or more days for some communal gardening, urban farm maintenance, and neighborhood beautification in the Northeast Bronx. Training provided. To RSVP or for additional volunteer days and times, email [email protected] AFTER HOLIDAY WEEKEND CLEAN UPS • VAN CORTLANDT PARK ALLIANCE Tuesday, July 6 • 9 a.m.–12 p.m. Van Cortlandt Park Help us clean up the park after July 4th! Join us to give VCP some much needed TLC. For more events in the park, visit https://live-vancortlandt.pantheonsite.io/calendar-of-events/ COMMUNITY VOLUNTEERS TO HELP WITH SYEP • FRIENDS OF MOSHOLU PARKLAND 6 weeks, July 6–August 13 • 8 a.m.–1 p.m. Mosholu Parkland • 3400 Reservoir Oval East Guide students to help clean up Mosholu Parkland, our six playgrounds, and the Keepers House Edible Garden. Tasks include painting pillars and benches, mulching walking paths, tree pit care, weeding, groundskeeping, helping at community gardens, and more. -

2017 Community Action Plan for Coney Island Creek & Parklands

Making Waves 2017 community action plan Coney Island Creek & Parklands Coney Island Creek & Parklands Cover photo: Coney island Creek. Credit: Charles Denson. Inside cover: City Parks Foundation Coastal Classroom students working together in Kaiser Park. All photos in this plan by the Partnerships for Parks Catalyst Program, unless otherwise noted. Table of Contents Working In Partnership Community leadership in restoring the Creek Coney Island Creek: History & Challenges Reversing a century of neglect Water Quality Restoring and protecting the Creek Public Engagement and Education Community building for a lifetime relationship with our environment Access and On-Water Programming A community that connects with its water cares for its water Resiliency and Flood Protection Protecting our community and enhancing natural assets Blueways and Greenways Connecting Coney Island to New York City: ferry service, paddling, and biking Connecting community to Coney Island Creek. Members of Coney Island Explorers and Coney Island Girl Scouts on a NYC Parks guided trip to discover and monitor Creating Community in our Parks and Open Spaces horseshoe crabs. Citizen science projects are part of the community plan to gauge the Sustaining thriving parks and public spaces for generations health of the Creek estuary. Photo: Eddie Mark Coney Island Creek & Parklands Making Waves Community Action Plan Page 3 WORKING IN PARTNERSHIP Community leadership in restoring the Creek CONEY ISLAND BEAUTIFICATION PROJECT is an environmental THE CONEY ISLAND HISTORY PROJECT, founded in 2004, is a 501(c)(3) not- organization that came into existence to help our community respond to the huge for-profit organization that aims to increase awareness of Coney Island's legendary impacts of Superstorm Sandy. -

47 City Council District Profiles

BROOKLYN Bensonhurst East, Homecrest, Gravesend, CITY Bensonhurst West, Bath Beach, West Brighton, COUNCIL 2009 DISTRICT 47 Seagate, Coney Island Parks are an essential city service. They are the barometers of our city. From Flatbush to Flushing and Morrisania to Midtown, parks are the front and backyards of all New Yorkers. Well-maintained and designed parks offer recreation and solace, improve property values, reduce crime, and contribute to healthy communities. SHOWCASE : Coney Island Beach & Boardwalk The Report Card on Beaches is modeled after New Yorkers for Parks’ award-winning Report Card on Parks. Through the results of independent inspections, it tells New Yorkers how well the City’s seven beaches are maintained in four key service areas: shorelines, pathways, bathrooms, and drink- ing fountains. The Report Card on Beaches is an effort to highlight these important facilities and Century Playground, Coney Island ensure that New York City’s 14 The Bloomberg Administration’s physical barriers or crime. As a result, miles of beaches are open, clean, and safe. Coney Island Beach is PlaNYC is the first-ever effort to studies show significant increases in one of the seven public beaches sustainably address the many infra- nearby real estate values. Greenways owned and operated by the structure needs of New York City, are expanding waterfront access City’s Parks Department. In 2007, including parks. With targets set for while creating safer routes for cyclists this beach was rated “unsatisfac- stormwater management, air quality and pedestrians, and the new initia- tory.” Its shoreline, bathrooms and more, the City is working to tive to reclaim streets for public use and drinking fountains performed update infrastructure for a growing brings fresh vibrancy to the city. -

Rare and Endangered Plants at Gateway National Recreation Area: a Case for Protection of Urban Natural Areas John T

Molloy College DigitalCommons@Molloy Faculty Works: CERCOM CERCOM 7-1996 Rare and endangered plants at Gateway National Recreation Area: a case for protection of urban natural areas John T. Tanacredi Ph.D. Molloy College, [email protected] Richard Stalter Saint Johns University Michael D. Byer Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.molloy.edu/cercom_fac Part of the Aquaculture and Fisheries Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Environmental Chemistry Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Environmental Monitoring Commons, Marine Biology Commons, Sustainability Commons, and the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons DigitalCommons@Molloy Feedback Recommended Citation Tanacredi, John T. Ph.D.; Stalter, Richard; and Byer, Michael D., "Rare and endangered plants at Gateway National Recreation Area: a case for protection of urban natural areas" (1996). Faculty Works: CERCOM. 8. https://digitalcommons.molloy.edu/cercom_fac/8 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the CERCOM at DigitalCommons@Molloy. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Works: CERCOM by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Molloy. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. Rare and endangered plants at Gateway National Recreation Area: a case for protection of urban natural areas Richard Stalter Michael D. Byer John T. Tanacredi Abstract The diversity of native plant species in urban environments is usually overlooked when biodiversity levels are considered. Inventories of native plants reveal many to be rare species surviving the harsh conditions encountered in urban ecosystems. Knowledge of their existence and an inventory of their distribution will assist in maintaining these populations. -

July 8 Grants Press Release

CITY PARKS FOUNDATION ANNOUNCES 109 GRANTS THROUGH NYC GREEN RELIEF & RECOVERY FUND AND GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC GRANT APPLICATION NOW OPEN FOR PARK VOLUNTEER GROUPS Funding Awarded For Maintenance and Stewardship of Parks by Nonprofit Organizations and For Free Live Performances in Parks, Plazas, and Gardens Across NYC July 8, 2021 - NEW YORK, NY - City Parks Foundation announced today the selection of 109 grants through two competitive funding opportunities - the NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund and GREEN / ARTS LIVE NYC. More than ever before, New Yorkers have come to rely on parks and open spaces, the most fundamentally democratic and accessible of public resources. Parks are critical to our city’s recovery and reopening – offering fresh air, recreation, and creativity - and a crucial part of New York’s equitable economic recovery and environmental resilience. These grant programs will help to support artists in hosting free, public performances and programs in parks, plazas, and gardens across NYC, along with the nonprofit organizations that help maintain many of our city’s open spaces. Both grant programs are administered by City Parks Foundation. The NYC Green Relief & Recovery Fund will award nearly $2M via 64 grants to NYC-based small and medium-sized nonprofit organizations. Grants will help to support basic maintenance and operations within heavily-used parks and open spaces during a busy summer and fall with the city’s reopening. Notable projects supported by this fund include the Harlem Youth Gardener Program founded during summer 2020 through a collaboration between Friends of Morningside Park Inc., Friends of St. Nicholas Park, Marcus Garvey Park Alliance, & Jackie Robinson Park Conservancy to engage neighborhood youth ages 14-19 in paid horticulture along with the Bronx River Alliance’s EELS Youth Internship Program and Volunteer Program to invite thousands of Bronxites to participate in stewardship of the parks lining the river banks. -

Departmentof Parks

ANNUAL REPORT OF THE DEPARTMENTOF PARKS BOROUGH OF THE BRONX CITY OF NEW YORK JOSEPH P. HENNESSY, Commissioner HERALD SQUARE PRESS NEW YORK DEPARTMENT OF PARKS BOROUGH OF 'I'HE BRONX January 30, 1922. Hon. John F. Hylan, Mayor, City of New York. Sir : I submit herewith annual report of the Department of Parks, Borough of The Bronx, for 1921. Respect fully, ANNUAL REPORT-1921 In submitting to your Honor the report of the operations of this depart- ment for 1921, the last year of the first term of your administration, it will . not be out of place to review or refer briefly to some of the most important things accomplished by this department, or that this department was asso- ciated with during the past 4 years. The very first problem presented involved matters connected with the appropriation for temporary use to the Navy Department of 225 acres in Pelham Bay Park for a Naval Station for war purposes, in addition to the 235 acres for which a permit was given late in 1917. A total of 481 one- story buildings of various kinds were erected during 1918, equipped with heating and lighting systems. This camp contained at one time as many as 20,000 men, who came and went constantly. AH roads leading to the camp were park roads and in view of the heavy trucking had to be constantly under inspection and repair. The Navy De- partment took over the pedestrian walk from City Island Bridge to City Island Road, but constructed another cement walk 12 feet wide and 5,500 feet long, at the request of this department, at an expenditure of $20,000. -

New York City Comprehensive Waterfront Plan

NEW YORK CITY CoMPREHENSWE WATERFRONT PLAN Reclaiming the City's Edge For Public Discussion Summer 1992 DAVID N. DINKINS, Mayor City of New lVrk RICHARD L. SCHAFFER, Director Department of City Planning NYC DCP 92-27 NEW YORK CITY COMPREHENSIVE WATERFRONT PLAN CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMA RY 1 INTRODUCTION: SETTING THE COURSE 1 2 PLANNING FRA MEWORK 5 HISTORICAL CONTEXT 5 LEGAL CONTEXT 7 REGULATORY CONTEXT 10 3 THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 17 WATERFRONT RESOURCES AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE 17 Wetlands 18 Significant Coastal Habitats 21 Beaches and Coastal Erosion Areas 22 Water Quality 26 THE PLAN FOR THE NATURAL WATERFRONT 33 Citywide Strategy 33 Special Natural Waterfront Areas 35 4 THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 51 THE EXISTING PUBLIC WATERFRONT 52 THE ACCESSIBLE WATERFRONT: ISSUES AND OPPORTUNITIES 63 THE PLAN FOR THE PUBLIC WATERFRONT 70 Regulatory Strategy 70 Public Access Opportunities 71 5 THE WORKING WATERFRONT 83 HISTORY 83 THE WORKING WATERFRONT TODAY 85 WORKING WATERFRONT ISSUES 101 THE PLAN FOR THE WORKING WATERFRONT 106 Designation Significant Maritime and Industrial Areas 107 JFK and LaGuardia Airport Areas 114 Citywide Strategy fo r the Wo rking Waterfront 115 6 THE REDEVELOPING WATER FRONT 119 THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT TODAY 119 THE IMPORTANCE OF REDEVELOPMENT 122 WATERFRONT DEVELOPMENT ISSUES 125 REDEVELOPMENT CRITERIA 127 THE PLAN FOR THE REDEVELOPING WATERFRONT 128 7 WATER FRONT ZONING PROPOSAL 145 WATERFRONT AREA 146 ZONING LOTS 147 CALCULATING FLOOR AREA ON WATERFRONTAGE loTS 148 DEFINITION OF WATER DEPENDENT & WATERFRONT ENHANCING USES -

Great Kills Harbor Breakwater Study: Hydrodynamic Modeling

DECEMBER, 2014 NEW ENGLAND INTERSTATE WATER POLLUTION CONTROL COMMISSION GREAT KILLS HARBOR BREAKWATER STUDY: HYDRODYNAMIC MODELING TASK 3 SUMMARY REPORT ADDRESS SCAPE / LANDSCAPE ADDRESS Ocean and Coastal ARCHITECTURE PLLC Consultants, Inc. 277 Broadway 35 Corporate Drive Suite 1606 Suite 1200 New York, NY 10007 Trumbull, CT 06611 TEL 212-462-2628 TEL 203-268-5007 FAX 212-462-4164 FAX 203-268-8821 WWW scapestudio.com WWW ocean-coastal.com GREAT KILLS HARBOR BREAKWATER STUDY: HYDRODYNAMIC MODELING TASK 3 SUMMARY REPORT PROJECT NO. 214038 DOCUMENT NO. T3_01 VERSION 2.0 DATE OF ISSUE December 19, 2014 PREPARED BRCO CHECKED TPMA APPROVED AZSL S:\OCC\Projects\2014\OCC_214038.0\3_Project_Files\Reports\Task 3 Modeling\20141219 Final V2.0\214038-3_Task3Summary_BRCO_2.0.docx TASK 3 SUMMARY 5 Task Introduction and Scope The Evaluation of an Offshore Breakwater System Adjacent to and South of Great Kills Harbor is co-led by Ocean & Coastal Consultants, a COWI Company and SCAPE Landscape Architecture (OCC/SCAPE) along with project partners ARCADIS US, Inc., Parsons Brinckerhoff, Biohabitats, and SeArc Marine Consulting. This feasibility study will provide guidance on the use of offshore breakwaters as an adaptation strategy to reduce wave action while maintaining or enhancing habitat value. The project’s objective seeks to determine the technical feasibility and marine habitat benefits and impacts offered by an offshore breakwater system outside of and adjacent to Great Kills Harbor. The results of the study will serve to inform New York City's Office of Recovery and Resiliency (ORR), New York City Department of City Planning, New York State's Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) and the Hudson River Estuary Program (HREP), and other agencies and community groups for use in community planning, shoreline adaptation, and resiliency. -

NYC Park Crime Stats

1st QTRPARK CRIME REPORT SEVEN MAJOR COMPLAINTS Report covering the period Between Jan 1, 2018 and Mar 31, 2018 GRAND LARCENY OF PARK BOROUGH SIZE (ACRES) CATEGORY Murder RAPE ROBBERY FELONY ASSAULT BURGLARY GRAND LARCENY TOTAL MOTOR VEHICLE PELHAM BAY PARK BRONX 2771.75 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 VAN CORTLANDT PARK BRONX 1146.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 ROCKAWAY BEACH AND BOARDWALK QUEENS 1072.56 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 FRESHKILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 913.32 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FLUSHING MEADOWS CORONA PARK QUEENS 897.69 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01002 03 LATOURETTE PARK & GOLF COURSE STATEN ISLAND 843.97 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 MARINE PARK BROOKLYN 798.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BELT PARKWAY/SHORE PARKWAY BROOKLYN/QUEENS 760.43 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 BRONX PARK BRONX 718.37 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 01000 01 FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT BOARDWALK AND BEACH STATEN ISLAND 644.35 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 ALLEY POND PARK QUEENS 635.51 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 PROSPECT PARK BROOKLYN 526.25 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 04000 04 FOREST PARK QUEENS 506.86 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GRAND CENTRAL PARKWAY QUEENS 460.16 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 FERRY POINT PARK BRONX 413.80 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CONEY ISLAND BEACH & BOARDWALK BROOKLYN 399.20 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 CUNNINGHAM PARK QUEENS 358.00 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00001 01 RICHMOND PARKWAY STATEN ISLAND 350.98 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 CROSS ISLAND PARKWAY QUEENS 326.90 ONE ACRE OR LARGER 0 00000 00 GREAT KILLS PARK STATEN ISLAND 315.09 ONE ACRE -

Bronx Brooklyn Manhattan Queens

CONGRATULATIONS OCTOBER 2018 CAPACITY FUND GRANTEES BRONX Concrete Friends – Concrete Plant Park Friends of Pelham Parkway Jackson Forest Community Garden Jardín de las Rosas Morrisania Band Project – Reverend Lena Irons Unity Park Rainbow Garden of Life and Health – Rainbow Garden Stewards of Upper Brust Park – Brust Park Survivor I Am – Bufano Park Teddy Bear Project – Street Trees, West Farms/Crotona Woodlawn Heights Taxpayers Association – Van Cortlandt Park BROOKLYN 57 Old Timers, Inc. – Jesse Owens Playground Creating Legacies – Umma Park Imani II Community Garden NYSoM Group – Martinez Playground Prephoopers Events – Bildersee Playground MANHATTAN The Dog Run at St. Nicholas Park Friends of St. Nicholas Park (FOSNP) Friends of Verdi Square Muslim Volunteers for New York – Ruppert Park NWALI - No Women Are Least International – Thomas Jefferson Park Regiven Environmental Project – St. Nicholas Park Sage’s Garden QUEENS Bay 84th Street Community Garden Elmhurst Supporters for Parks – Moore Homestead Playground Forest Park Barking Lot Friends of Alley Pond Park Masai Basketball – Laurelton Playground Roy Wilkins Pickleball Club – Roy Wilkins Recreation Center STATEN ISLAND Eibs Pond Education Program, Inc. (Friends of) – Eibs Pond Park Friends of Mariners Harbor Parks – The Big Park Labyrinth Arts Collective, Inc. – Faber Pool and Park PS 57 – Street Trees, Park Hill CITYWIDE Historic House Trust of New York City Generous private support is provided by the Altman Foundation and the MJS Foundation. Public support is provided by the NYC Council under the leadership of Speaker Corey Johnson through the Parks Equity Initiative. . -

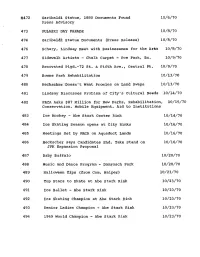

I. for Release

#472 Garibaldi Statue, 1880 Documents Found 10/6/70 Press Advisory 473 PULASKI DAY PARADE 10/8/70 474 Garibaldi Statue Documents (Press Release) 10/8/70 476 Senary, Lindsay Meet with Businessmen for the Arts 10/8/70 477 Sidewalk Artists - Chalk Carpet - Poe Park, Bx. 10/9/70 478 Renovated Plgd.-72 St. & Fifth Ave., Central Pk. 10/9/70 479 Bowne Park Rehabilitation 10/13/70 480 HecksfcherrDoesn1t Want Promies on Land Swaps 10/13/70 481 Lindsay Discusses Problem of City's Cultural Needs 10/14/70 482 PRCA Asks $87 Million for New Parks, Rehabilitation, 10/15/70 Conservation, Mobile Equipment, Aid to Institutions 483 Ice Hockey - Abe Stark Center Rink 10/14/70 484 Ice Skating Season opens at City Rinks 10/16/70 485 Meetings Set by PRCA on Aqueduct Lands 10/16/70 486 Heckscher says Candidates Shd. Take Stand on 10/16/70 JFK Expansion Proposal 487 Baby Buffalo 10/20/70 488 Music and Dance Program - Damrosch Park 10/20/70 489 Halloween Tips (from Com,. Halper) 10/23/70 490 Top Stars to Skate at Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 491 Ice Ballet - Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 492 Ice Skating Champion at Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 493 Senior Ladies Champion - Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 494 1969 World Champion - Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 495 Middle Atlantic Skating Champion - Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 496 Eastern Jr. Men's Champion - Abe Stark Rink 10/23/70 497 Eye Opener - Bronx 10/23/70 498 Free Film - Brazilian Peasants- "Antonio Das Mortes" 10/23/70 499 Community Meeting to Discuss Playground-Mullaly Park 10/23/70 501 Bicycling-C.P.