Proposal to Establish a Povertyfighting Wine Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the French in London Liberty, Equality, Opportunity

A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity A history of the French in London liberty, equality, opportunity Edited by Debra Kelly and Martyn Cornick LONDON INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Published by UNIVERSITY OF LONDON SCHOOL OF ADVANCED STUDY INSTITUTE OF HISTORICAL RESEARCH Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU First published in print in 2013. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY- NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978 1 909646 48 3 (PDF edition) ISBN 978 1 905165 86 5 (hardback edition) Contents List of contributors vii List of figures xv List of tables xxi List of maps xxiii Acknowledgements xxv Introduction The French in London: a study in time and space 1 Martyn Cornick 1. A special case? London’s French Protestants 13 Elizabeth Randall 2. Montagu House, Bloomsbury: a French household in London, 1673–1733 43 Paul Boucher and Tessa Murdoch 3. The novelty of the French émigrés in London in the 1790s 69 Kirsty Carpenter Note on French Catholics in London after 1789 91 4. Courts in exile: Bourbons, Bonapartes and Orléans in London, from George III to Edward VII 99 Philip Mansel 5. The French in London during the 1830s: multidimensional occupancy 129 Máire Cross 6. Introductory exposition: French republicans and communists in exile to 1848 155 Fabrice Bensimon 7. -

Riboli Family of San Antonio Winery

THE SEPTEMBER 2018 • $6.95 TASTING PANEL TASTING MAGAZINE MAGAZINE • SEPTEM B ER 2018 meet MADDALENA RIBOLI THE ICON SHARES HER VISION FOR THE RIBOLI FAMILY OF SAN ANTONIO WINERY TP0918_ .indd 1 8/30/18 2:09 PM TP0918_068-100_KNV2.inddTP0918_068-100_KNV2.indd 100 101 8/29/18 1:34 8/29/18PM 1:34TP0918_001-31_KNV2.indd PM 1 8/30/18 4:23 PM ONE RYE. TWO ESTATES. tastingpanel The Man Behind the Brands SMOGÓRY FOREST SMOGÓRY FOREST is bold and savory, made from Dankowskie ins Diamond rye born in the lush forests of Western Poland. l El chae © Mi oto Ph . C LL , ts, piri S 123spirits.com 23 17 1 20 EU Organic © ONE RYE. TWO ESTATES. TP0918_ .indd 2 123 Spirits 6 Bottle_Ad_TastingPanel_8.375x10.875.indd 1 8/30/189/19/17 6:344:19 MPM TP0918_001-31_KNV2.indd 2 8/29/18 1:34 PM TP0918_068-100_KNV2.indd 99 8/29/18 1:34 PM ONE RYE. TWO ESTATES. tastingTHE panel MAGAZINE September 2018 • Vol. 76 No. 8 editor in chief publisher / editorial director vp / associate publisher managing editor Anthony Dias Blue Meridith May Rachel Burkons Jesse Hom-Dawson [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 818-990-0350 senior design director senior wine editor Michael Viggiano [email protected] Jessie Birschbach [email protected] vp, sales and marketing senior editor Bill Brandel [email protected] Kate Newton [email protected] special projects editor CONTRIBUTORS David Gadd [email protected] Jeremy Ball, Claire Barrett, Rachel Coward, Madelyn Gagnon, east coast editor -

Wine List, Ready for the Spring and Summer of What Will Be, and to Be Honest Is Already, a Year Which We Will Never Forget

Pouring great wines and serving simple, delicious Other drinks seasonal food, Vinoteca is a group of informal wine bars 5 The rest of our line-up: beers, spirits, wine cocktails, and shops. Over 200 wines listed, 25 by the glass served low/non alcoholic, soft and hot drinks. from bottle, can, box and keg, and every wine available Favourites to take away and enjoy at home. 8 The wines that our staff just can't stop drinking. Even though they probably should. Chiswick 18 Devonshire Road, W4 2HD Organic and biodynamic [email protected] 020 3701 8822 10 Harmony and biodiversity in the vineyard. It's what our children want! City Sparkling 21 Bloomberg Arcade, EC4N 8AR 14 Classic bubbles to funky fizz from round the world, [email protected] 020 3150 1292 from bone dry to rich and toasty. White Farringdon 15 The whole range, from racy & refreshing to fruity & aromatic, from 7 St John Street, EC1M 4AA complex & savoury to rich & opulent. [email protected] 020 7253 8786 15 Argentina King's Cross 15 Australia 15 Austria 3 King's Boulevard, N1C 4BU 16 England [email protected] 020 3793 7210 16 France Marylebone 18 Georgia 18 Germany 15 Seymour Place, W1H 5BD 18 Greece [email protected] 020 7724 7288 18 Hungary Wine Online 18 Italy 20 New Zealand Wine Club: vinoteca.co.uk/wine-club 20 Portugal Online Shop: shop.vinoteca.co.uk 20 Romania 21 South Africa 21 Spain 21 USA vinoteca.co.uk 3 Rose WINE COCKTAILS & COOLERS 22 Fresh, vibrant, moreish. -

Manganeso Y Viticultura: Una Revisión

El ManganesoMangganeso y lala Viticultura:Viticultura: unauna revisiónrevisión V.V. D.D. GGómezómez-MiguelMiguell & V.V. SotésSotés MadridMadrid-20142014 El Manganeso y la Viticultura: una revisión Madrid, 2014 Aviso Legal: los contenidos de esta publicación podrán ser reutilizados, citando la fuente y la fecha, en su caso, de la última actualización. El Manganeso y la Viticultura: Una revisión Autores: V. D. Gómez-Miguel, V. Sotés. E.T.S. de Ingenieros Agrónomos. Universidad Politécnica de Madrid. Los resultados fueron presentados por los autores, como miembros de la delegación española del Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente, en la Reunión de la Organización Inter - nacional de la Viña y el Vino (OIV) del 3 de abril de 2014. Los autores agradecen a la Subdirección General de Control y de Laboratorios Alimentarios, de la Dirección General de la Industria Alimentaria, y en especial al Laboratorio Arbitral Agroalimentario por el asesoramiento técnico y científico aportado para la publicación de este trabajo. MINISTERIO DE AGRICULTURA, ALIMENTACIÓN Y MEDIO AMBIENTE Edita: Distribución y venta: © Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente Paseo de la Infanta Isabel, 1 Secretaría General Técnica 28014 Madrid Centro de Publicaciones Teléfono: 91 347 55 41 Fax: 91 347 57 22 Diseño y maquetación: Los autores Tienda virtual: www.magrama.es [email protected] Impresión y encuadernación: Talleres del Centro de Publicaciones del MAGRAMA NIPO: 280-14-137-0 (papel) NIPO: 280-14-136-5 (línea) Depósito Legal: M-21419-2014 Catálogo de Publicaciones de la Administración General del Estado: http://publicacionesoficiales.boe.es/ Datos técnicos: Formato: 21x29,7 cm. Caja de texto: 16x25,5 cm. -

Report of a Working Group on Vitis: First Meeting

European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources Report of a Working ECP GR Group on Vitis First Meeting, 12-14 June 2003, Palić, Serbia and Montenegro E. Maul, J.E. Eiras Dias, H. Kaserer, T. Lacombe, J.M. Ortiz, A. Schneider, L. Maggioni and E. Lipman, compilers IPGRI and INIBAP operate under the name Bioversity International Supported by the CGIAR European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Resources Report of a Working ECP GR Group on Vitis First Meeting, 12-14 June 2003, Palić, Serbia and Montenegro E. Maul, J.E. Eiras Dias, H. Kaserer, T. Lacombe, J.M. Ortiz, A. Schneider, L. Maggioni and E. Lipman, compilers ii REPORT OF A WORKING GROUP ON VITIS: FIRST MEETING Bioversity International is an independent international scientific organization that seeks to improve the well-being of present and future generations of people by enhancing conservation and the deployment of agricultural biodiversity on farms and in forests. It is one of 15 centres supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), an association of public and private members who support efforts to mobilize cutting-edge science to reduce hunger and poverty, improve human nutrition and health, and protect the environment. Bioversity has its headquarters in Maccarese, near Rome, Italy, with offices in more than 20 other countries worldwide. The Institute operates through four programmes: Diversity for Livelihoods, Understanding and Managing Biodiversity, Global Partnerships, and Commodities for Livelihoods. The international -

Instituto De Ciencias Del Patrimonio

INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS DEL PATRIMONIO FOTO PORTADA CONSEJO SUPERIOR DE INVESTIGACIONES CIENTÍFICAS MEMORIA 2017/2019 1 INSTITUTO DE CIENCIAS DEL PATRIMONIO Web: www.incipit.csic.es Dirección: Avenida de Vigo s/nº, Campus Vida, Santiago de Compostela, ES-15705 Teléfono: +34 981 590 962 E-mail [email protected] Presentación El Instituto de Ciencias del Patrimonio (Incipit) del CSIC fue creado por acuerdo del Consejo Rector del CSIC el 26 de enero de 2010. Ha cumplido sus primeros diez años. El Incipit nació como un instituto de investigación orientado a problema. Su objetivo científico compartido es el estudiode la cadena de valor del Patrimonio Cultural, esto es: investigar los procesos que crean en el pasado y en el presente elementos a los cuales determinados procesos de valorización cultural otorgan carácter patrimonial, lo que 2 introduce esos bienes en la vida social y los convierte en coadyuvantes de todo tipo de usos comunitarios, que se relacionan con la identidad, la tradición, las costumbres y hábitos, la política, su instrumentación como recurso por movimientos sociales de un tipo u otro, como arma de conflicto o aglutinación, e incluso su rentabilización económica. En la actualidad no existe ningún proceso social ni político que no utilice el patrimonio de alguna forma. De ahí la actualidad del tema y la importancia de que un organismo como el CSIC tenga capacidades de investigación en este ámbito. Dado su objetivo científico, el Incipit no es un instituto definido disciplinarmente, sino de naturaleza multidisciplinar. Engloba personal de muchas disciplinas diferentes (arqueología, arquitectura, antropología, astrofísica, historia, ingeniería, física, geografía, paleoambiente, etc.) que trabajan juntos en el seno de proyectos que son más transdisciplinares que interdisciplinares. -

Wine by the Glass

Wine by the Glass Sparkling Jura Marnes Blanches Réserve 17 69 Chardonnay Champagne Tarlant ½ Bottle 49 Brut Nature Rosé Rhône Valley Isle Saint-Pierre 2016 17 65 Merlot Sherry & Aromatized Sierra Morena Gómez Nevado Dorado 12 Amontillado Brooklyn Uncouth Vermouth 15 Rhubarb White Franken Rudolf May 2014 13 52 Silvaner Burgenland Nittnaus 2015 14 55 Pinot Blanc Friuli Bastianich Orsone 2015 15 59 Pinot Grigio Long Island Macari 2015 16 64 Sauvignon Blanc Vouvray Brunet Renaissance 2015 18 72 Chenin Blanc Red Azay-le-Rideau Plateau 2015 12 47 Grolleau Long Island Shinn 14 55 Merlot Beaujolais Ruet Chiroubles 2014 15 58 Gamay Finger Lakes Eminence Road Hector 2015 16 62 Cab Franc Montalcino La Torre Ampelio 2014 16 63 Sangiovese & Alicante Sierra Foothills Terre Rouge 2012 17 68 Syrah Sparkling Wine Pinch x Aaron Burr Dump Road Fancy Lads, Deer Isle, Maine, 2015 CIDER 40 Angiolino Maule Garg’N’Go, Veneto, Italy, 2015 PÉT-NAT 45 Paltrinieri Lambrusco di Sorbara Leclisse, Emilia-Romagna, Italy ROSÉ 56 Léon Boesch Soixante-Douze, Alsace, France 59 La Clarine Farm Circles Don’t Fly…, Sierra Foothills, California, 2015 PÉT-NAT 61 Schramsberg Blanc de Blancs, North Coast, California, 2013 85 Under the Wire Alder Springs, Mendocino County, California, 2013 ROSÉ 125 Champagne Cramant Bl. de Blancs Lilbert-Fils ½ Bottle 63 Brut Étoges Bl. de Blancs Grongnet 66 Brut Cumières Georges Laval ½ Bottle 2010 73 Brut Nature Bl. de Noirs Les Hautes Chêvres Pinot Noir 2009 350 Brut Nature Essoyes Ruppert-Leroy Fosse-Grely 2011 99 Brut Nature Ambonnay ROSÉ Marguet Shaman Rosé 2012 115 Extra Brut Les Crayères 2009 199 Extra Brut Bl. -

Enblanco 10N.Indd

ENGLISH TEXT The magazine EN BLANCO is intended to diffuse knowledge of the best works of remains and the new museum to be built became part of an archaeological architecture and civil engineering made nowadays in concrete, preferably white and agricultural landscape, a witness of a remote past inserted among Andalusian or coloured. It is our intention to meet the interest of those who want to know the agricultural constructions. latest innovations in the fi eld of concrete architecture and at the same time, The romantic image of ruins, so many times rejected for being nostalgic and to serve as a disseminator of research emerged in the same fi eld. anachronistic, is, however, able to transmit not only the evocative power of ancient The purpose of EN BLANCO is to publish the results of formal, theoretical, constructions but also the destructive force of time and nature. Maybe it is in this technological and scientifi c research related to the production of buildings and duality –construction, deconstruction- where resides the fascination of archaeological engineering works that help defi ne our environment, built in concrete. remains, not only as the memory of missing buildings but as the trigger of the mental The magazine meets the formal and conceptual requirements that allow reconstruction of other future architectures. At least that is what we understood recognition as scientifi c publication. Thus the magazine follows a strict editorial during our fi rst visit to Medinat al-Zahra archaeological grounds. The remains of the policy, both in the selection of works and articles and in the periodicity and linguistic ancient Hispanic Muslim city suggested a dialogue with those who, a millennium ago, fi eld. -

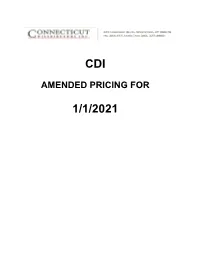

Cdi 1/1/2021

- CDI AMENDED PRICING FOR 1/1/2021 Also to be Hand filed for January Fleur Saint Antoine R 2018 12-750mls selling case price 73.83 6.23 min bottle Amended Prices for the Month of January 2021 Name of Licensee: Date:12/15/2020 Initial Filing Amending To Notes1 Item # Item Bottle Case Resale Bott PO Case PO Amending To Bottle Case Resale Bott PO Case PO 9006513 ANTIOQUEN O AGUARDIEN TE 1L 21.49 256.92 26.99 HARTLEY & PARKER 17.99 190.92 27.99 48.00 72.00 9006515 ANTIOQUEN O AGUARDIEN TE 375ML 9.49 225.84 11.99 HARTLEY & PARKER 7.99 165.84 11.99 36.00 60.00 9006514 ANTIOQUEN O AGUARDIEN TE 750ML 17.49 208.92 22.99 HARTLEY & PARKER 15.99 166.92 22.99 24.00 48.00 9197218 APPLETON EST RUM 12YR RARE BLND 6B 750ML 34.49 412.92 38.49 24.00 24.00 EDER BROTHERS 32.49 388.92 43.94 24.00 24.00 26229 APPLETON EST RUM VX SIG BLD 1.75L 34.49 206.46 45.21 12.00 12.00 EDER BROTHERS 34.49 182.46 46.49 12.00 36.00 9024341 APPLETON EST RUM VX SIG BLD 750ML 18.49 196.92 24.99 12.00 36.00 EDER BROTHERS 17.74 184.92 23.87 12.00 36.00 153445 BALLANTINE S SCOTCH FINEST 750ML 19.30 229.15 24.39 EDER BROTHERS 19.11 226.92 24.99 9008692 BALVENIE SCOTCH 12YR DOUBLEWO OD 750ML 54.99 654.92 59.99 24.00 24.00 BARTON BRESCOME 54.66 642.92 67.49 24.00 36.00 9083417 BALVENIE SCOTCH 21YR PORT WD 3B 750ML 229.99 2752.32 279.99 BARTON BRESCOME 217.64 2604.12 299.99 240.00 240.00 9005867 BALVENIE SCOTCH 30YR 3B 750ML 1066.99 12511.88 1259.99 BARTON BRESCOME 1042.74 12511.88 1327.99 9130579 BALVENIE SCOTCH 40YR 1B 750ML 4837.99 58046.76 5394.99 BARTON BRESCOME 4837.31 58046.76 -

Brunello Di Montalcino

BUYING GUIDE MAY 2013 The view from a vineyard in Montalcino. 61 WASHINGTON 2 TUSCANY 63 IDAHO 24 BORDEAUX 64 VIRGINIA 31 CHAMPAGNE 65 NEW YORK 33 SPAIN 68 SPIRITS 41 SOUTH AFRICA 70 BEER 44 ARGENTINA FOR ADDITIONAL RATINGS AND REVIEWS, VISIT 46 CALIFORNIA BUYINGGUIDE.WINEMAG.COM MICK ROCK/CEPHAS WineMag.com | 1 TUSCANY THE 90-POINT 2008 VINTAGE IN BRUNELLO DI MONTALCINO he 2008 Brunello di Montalcino—arguably Italy’s favorite wine—has “Acidity can be a determining factor in the longevity of a Brunello,” says recently hit the market. Many consumers are wondering what to ex- vintner Donatella Cinelli Colombini. “The key, however, is finding wines Tpect from the vintage, which I have rated 90 out of 100 points. Will that show balance and harmony in the manner that acidity is delivered.” the new vintage be as well received as the soft, rich wines of 2007 and the The Consorzio seems to think the 2008 shows that balance, scoring the elegant, refined wines of 2006? vintage four out of five stars. The 2006 and 2007 vintages both received Austerity—an overused word in the corridors of European government five stars from the Consorzio, and I awarded them 93 points and 95 points, and finance agencies these days—happens to perfectly describe these respectively. wines. The 2008 summer was cool and moderate in temperature, and there In addition to checking out the 2008s, I also reviewed many recently re- were hailstorms and showers at certain locations on the southern side of leased 2007 Riserva Brunellos this month. As you will see from the scores, the appellation just before harvest, resulting in wines with high acidity and the quality of the vintage is undeniable, with more than 75% of the wines bright berry tones. -

Environmentally Sustainable Viticulture

Mobile Register Log In Access provided by "Agriculture and Full Access Content Only Search Agri-Food Canada, Canadian Agriculture Library" Advanced Search Home Browse Content Advanced Search About CRCnetBASE Subject Collections How to Subscribe Librarian Resources News & Events Free Trial About this Book Environmentally Sustainable Viticulture Citation Information Environmentally Sustainable Viticulture Practices and Practicality Edited by Chris Gerling Apple Academic Press 2015 Print ISBN: 978-1-77188-112-8 eBook ISBN: 978-1-4987-2229-2 Table of Contents Download Citations. View Abstracts Add to Bookshelf Email Access Page Title Search i Front Matter Simple Search Advanced Search Abstract - Hi-Res PDF (620 KB) - PDF w/links (620 KB) All books 1Part I. Overview This book Abstract - Hi-Res PDF (136 KB) - PDF w/links (137 KB) 3 Chapter 1. Sustainability in the Wine Industry: Key Questions and Research Trends Sélectionner une langue ▼ Cristina Santini, Alessio Cavicchi, Leonardo Casini Translator disclaimer Abstract - Hi-Res PDF (330 KB) - PDF w/links (373 KB) 25 Chapter 2. From Environmental to Sustainability Programs: A Review of Sustainability Initiatives in the Italian Wine Sector Chiara Corbo, Lucrezia Lamastra, Ettore Capri Abstract - Hi-Res PDF (405 KB) - PDF w/links (427 KB) 61 Chapter 3. Transnational Comparison of Sustainability Assessment Programs for Viticulture and a Case-Study on Programs’ Engagement Processes Irina Santiago-Brown, Andrew Metcalfe, Cate Jerram, Cassandra Collins Abstract - Hi-Res PDF (592 KB) - PDF w/links (648 KB) 105 Part II. Elements of Sustainable Viticulture: From Land and Water Use to Disease Management Abstract - Hi-Res PDF (137 KB) - PDF w/links (138 KB) 107 Chapter 4. -

Grape Pomaces)

Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Chemical and Bioengineering Extraction and Characterization of Antioxidants from Wine By- Product (Grape Pomaces) Tamirat Endale A Thesis Submitted to The School of Chemical and Bio Engineering Presented in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Masters of Science (Chemical and Bio Engineering) Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June 19, 2017 i Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa Institute of Technology School of Chemical and Bioengineering This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Tamirat Endale entitled: Extraction and Characterization of Antioxidants from Wine By-Product (Grape Pomaces) and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Sciences (Chemical and Bio Engineering) complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the Examining Committee: Examiner Signature Date Examiner Signature Date Advisor Adamu Zegeye (Associate Professor) Signature Date ii Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank Almighty God, the source of all knowledge and wisdom. God because nothing could be possible without His help, to all above I would to express my sincerest gratitude, many thanks! I thank my advisor, Adamu Zegeye (Associate professor), for his contributions during the entire course of this work’s progress. Not only his constant technical advice but also his guidance in terms of psychological supports was truly motivational all along. Once again, I wish to express my genuine gratefulness to him for his constructive ideas, advices and motivations from the beginning to the end of this work.