Nixonian Foreign Policy and the Changing Canadian American Relationship

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (PDF)

N° 3/2019 recherches & documents March 2019 Disarmament diplomacy Motivations and objectives of the main actors in nuclear disarmament EMMANUELLE MAITRE, research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-490100-19-4 EAN : 9782490100194 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1 – A CONVERGENCE OF PACIFIST AND HUMANITARIAN TRADITIONS ....................................... 8 1.1 – Neutrality, non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament .......................... 8 1.1.1 – Disarmament in the neutralist tradition .............................................................. 8 1.1.2 – Nuclear disarmament in a pacifist perspective .................................................. 9 1.1.1 – "Good international citizen" ..............................................................................11 1.2 – An emphasis on humanitarian issues ...............................................................13 1.2.1 – An example of policy in favor of humanitarian law ............................................13 1.2.2 – Moral, ethics and religion .................................................................................14 -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

R=Nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- R.104TA (-{, 001

3Kcnen~lHrn 3 . ~ ,_ CCCP r=nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- r.104TA (-{, 001 diasporiana.org.ua CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON CANADIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS Unive~ty Partnership Centre I Georgian College, Barrie, ON Vol. 9 I Canada/Russia Series J.L. Black ef Andrew Donskov, general editors CRCR One-Way Ticket The Soviet Return-to-the-Homeland Campaign, 1955-1960 Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko Penumbra Press I Manotick, ON I 2008 ,l(apyHoK OmmascbKozo siooiny KaHaOCbKozo Tosapucmsa npuHmeniB YKpai°HU Copyright © 2008 Library and Archives Canada SERGE CIPKO & GLENNA ROBERTS Cataloguing-in-Publication Data No part of this publication may be Roberts, Glenna, 1934- reproduced, stored in a retrieval system Cipko, Serge, 1961- or transmitted, in any1'0rm or by any means, without the prior written One-way ticket: the Soviet return-to consent of the publisher or a licence the-homeland campaign, 1955-1960 I from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko. Agency (Access Copyright). (Canada/Russia series ; no. 9) PENUMBRA PRESS, publishers Co-published by Centre for Research Box 940 I Manotick, ON I Canada on Canadian-Russian Relations, K4M lAB I penumbrapress.ca Carleton University. Printed and bound by Custom Printers, Includes bibliographical references Renfrew, ON, Canada. and index. PENUMBRA PRESS gratefully acknowledges ISBN 978-1-897323-12-0 the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing L Canadians-Soviet Union Industry Development Program (BPIDP) History-2oth century. for our publishing activities. We also 2. Repatriation-Soviet Union acknowledge the Government of Ontario History-2oth century. through the Ontario Media Development 3. Canadians-Soviet Union Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative. -

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 957 18 June 2020

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 957 18 June 2020 Luc-André Brunet. “Unhelpful Fixer? Canada, the Euromissile Crisis, and Pierre Trudeau’s Peace Initiative, 1983–1984.” The International History Review 41:6 (2019): 1145-1167. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1472623. https://hdiplo.org/to/AR957 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Commissioning Editor: Cindy Ewing | Production Editor: George Fujii Review by Greg Donaghy, University of Toronto here are very few episodes in Canada’s diplomatic history—and none so unsuccessful—that that have attracted the scholarly ink reserved for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s controversial peace initiative at the height of the second T Cold War in the fall of 1983.1 The latest entry is Luc-André Brunet’s award-winning article, “Unhelpful Fixer? Canada, the Euromissile Crisis, and Pierre Trudeau’s Peace Initiative, 1983-1984.” Superbly researched in seven national archives, carefully argued, and presented with verve and spirit, “Unhelpful Fixer” will quite probably remain the last word on the subject for some time to come. For Brunet, the story starts in the summer of 1983, when Trudeau, already fifteen years in power, cast about for a dramatic foreign policy initiative that would restore his cratering poll numbers. Horrified by Moscow’s decision to shoot-down an errant Korean airliner over Soviet airspace on 1 September 1983, Trudeau leapt into action. Sidelining the foreign and defence policy establishment, he assembled a Task Force of mid-level officials, and asked it to cobble together a series of arms control and disarmament measures to “change the trend line” (1148) in East-West relations and reduce the brittle tensions between the United States and the USSR. -

What Has He Really Done Wrong?

The Chrétien legacy Canada was in such a state that it WHAT HAS HE REALLY elected Brian Mulroney. By this stan- dard, William Lyon Mackenzie King DONE WRONG? easily turned out to be our best prime minister. In 1921, he inherited a Desmond Morton deeply divided country, a treasury near ruin because of over-expansion of rail- ways, and an economy gripped by a brutal depression. By 1948, Canada had emerged unscathed, enriched and almost undivided from the war into spent last summer’s dismal August Canadian Pension Commission. In a the durable prosperity that bred our revising a book called A Short few days of nimble invention, Bennett Baby Boom generation. Who cared if I History of Canada and staring rescued veterans’ benefits from 15 King had halitosis and a professorial across Lake Memphrémagog at the years of political logrolling and talent for boring audiences? astonishing architecture of the Abbaye launched a half century of relatively St-Benoît. Brief as it is, the Short History just and generous dealing. Did anyone ll of which is a lengthy prelude to tries to cover the whole 12,000 years of notice? Do similar achievements lie to A passing premature and imperfect Canadian history but, since most buy- the credit of Jean Chrétien or, for that judgement on Jean Chrétien. Using ers prefer their own life’s history to a matter, Brian Mulroney or Pierre Elliott the same criteria that put King first more extensive past, Jean Chrétien’s Trudeau? Dependent on the media, and Trudeau deep in the pack, where last seven years will get about as much the Opposition and government prop- does Chrétien stand? In 1993, most space as the First Nations’ first dozen aganda, what do I know? Do I refuse to Canadians were still caught in the millennia. -

Canada Day As Part of a Political Master Brand

Celebrating the True North: Canada Day as part of a political master brand Justin Prno Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Department of Communication Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Justin Prno, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH ii Abstract In Canada, the rise of political branding coincided with the adoption of the permanent campaign, creating an environment in which politicking is now normalized and politicization is expected. With Canada Day 2017 as a case study, this thesis adopts Marland’s Branding Lens Thesis (2016) as a conceptual framework to analyze if a national holiday became part of the Liberal Party of Canada’s master brand. The key conclusion of this thesis is that the Liberals integrated their ‘master brand’ into Canada Day 2017 by integrating political branding into their government communications. This thesis also shows that Justin Trudeau played a bigger role during Canada Day than expected by a Prime Minister. Significantly, this thesis shows the Liberal government altered the themes and messaging of Canada 150 to parallel that of their master brand, applying a Liberal tint to Canada Day and Canada 150. CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH iii Acknowledgements I’ve been known to talk a lot, but when it comes to the written word, I often come up short. Either way here goes... I would like to thank the community of people that surround me, near and far, past and present. Having you as part of my life makes taking these trips around the sun far more enjoyable. -

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic

Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Engaging Iran Australian and Canadian Relations with the Islamic Republic Robert J. Bookmiller Gulf Research Center i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Dubai, United Arab Emirates (_}A' !_g B/9lu( s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ *_D |w@_> TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B uG_GAE#'c`}A' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB9f1s{5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'cAE/ i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBª E#'Gvp*E#'B!v,¢#'E#'1's{5%''tDu{xC)/_9%_(n{wGLi_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uAc8mBmA' , ¡dA'E#'c>EuA'&_{3A'B¢#'c}{3'(E#'c j{w*E#'cGuG{y*E#'c A"'E#'c CEudA%'eC_@c {3EE#'{4¢#_(9_,ud{3' i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uBB`{wB¡}.0%'9{ymA'E/B`d{wA'¡>ismd{wd{3 *4#/b_dA{w{wdA'¡A_A'?uA' k pA'v@uBuCc,E9)1Eu{zA_(u`*E @1_{xA'!'1"'9u`*1's{5%''tD¡>)/1'==A'uA'f_,E i_m(#ÆA Gulf Research Center 187 Oud Metha Tower, 11th Floor, 303 Sheikh Rashid Road, P. O. Box 80758, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. Tel.: +971 4 324 7770 Fax: +971 3 324 7771 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.grc.ae First published 2009 i_m(#ÆAk pA'v@uB Gulf Research Center (_}A' !_g B/9lu( Dubai, United Arab Emirates s{4'1q {xA' 1_{4 b|5 )smdA'c (uA'f'1_B%'=¡(/ © Gulf Research Center 2009 *_D All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in |w@_> a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, TBMFT!HSDBF¡CEudA'sGu( XXXHSDBFeCudC'?B mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Gulf Research Center. -

Canada's Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Canada’s Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia: An Assessment of the Trudeau Government’s First International Crisis by Angus McCabe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Angus McCabe ii Abstract The new government of Pierre Trudeau was faced with an international crisis when, on 20 August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. This study is the first full account of the Canadian government’s response based on an examination of the archival records of the Departments of External Affairs, National Defence, Manpower and Immigration, and the Privy Council Office. Underlying the government’s reaction were differences of opinion about Canada’s approach to the Cold War, its role at the United Nations and in NATO, the utility of the Department of External Affairs, and decisions about refugees. There was a delusory quality to each of these perspectives. In the end, an inexperienced government failed to heed some of the more competent advice it received concerning how best to meet Canada’s interests during the crisis. National interest was an understandable objective, but in this case, it was pursued at Czechoslovakia’s expense. iii Acknowledgements As anyone in my position would attest, meaningful work with Professor Norman Hillmer brings with it the added gift of friendship. The quality of his teaching, mentorship, and advice is, I suspect, the stuff of ages. I am grateful for the privilege of his guidance and comradeship. Graduate Administrator Joan White works kindly and tirelessly behind the scenes of Carleton University’s Department of History. -

Creation's Lab the Next Frontier in The

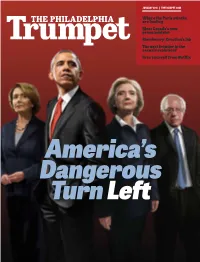

JANUARY 2016 | THETRUMPET.COM Where the Paris attacks are leading Meet Canada’s new prime minister Biomimicry: Creation’s lab The next frontier in the sexual revolution? Free yourself from Netflix America’s Dangerous Turn Left JANUARY 2016 VOL. 27, NO. 1 CIRC. 287,157 NIGHT OF TERROR A tarp covers one of the victims of the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris. (GETTY IMAGES) COVER GARY DORNING/TRUMPET Cover Story Features Unriddling the Radical Worldview From the Editor of President Obama 2 Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading 1 The Roots of America’s Dangerous Like Father, Like Son? 11 Turn Left 6 Canada’s democratic system has empowered a dynasty Why Educators Are Attracted to Communism 9 that’s not big on democracy. Justin Trudeau’s Vision for Canada 31 Fear This Man 12 It is dangerous to underestimate Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Departments Will Putin Reignite the Balkans? 14 Worldwatch Pressure on Merkel, admiration for Europe’s next crisis could hit in what used to be Yugoslavia. Hitler?, Putin—savior of Russians, etc. 26 How Europe Conquered the Balkans 16 Societywatch Record gun-sales, etc. 29 Infographic: Biomimicry—Learning From Creation 18 Principles of Living Your Glorious, God-Given Power 33 The Next Frontier in the Sexual Revolution? 20 Discussion Board 34 Free Yourself From Netflix 22 Commentary Teaching the Unteachable 35 Will the Two Chinas Become One? 23 The Key of David Television Log 36 The time when Taiwan will be swallowed is approaching. More Trumpet Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Trumpet executive editor Stephen News and analysis A weekly digest Flurry’s weekly television program Flurry’s television program updated daily of important news theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpet_daily theTrumpet.com theTrumpet.com/trumpetweekly From the Editor Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading Most people are focusing on France’s reaction—but the ultimate aftereffect will consume all of Europe. -

Defending the United States and Canada, in North America and Abroad

DEFENDING THE UNITED STATES AND CANADA, IN NORTH AMERICA AND ABROAD John J. Noble From Franklin Roosevelt’s Queen’s University address of 1938, the mutual defence of Canada and the United States has been the central tenet of Canadian foreign and defence policies. With rare exceptions, notably John Diefenbaker’s reneging on accepting nuclear Bomarc missiles in 1963, the policy of mutual defence has been adhered to by every Canadian government since Mackenzie King’s in the 1940s. Paul Martin’s decision not to participate in ballistic missile defence can be seen as a break with that tradition. John Noble, both a student and practitioner of Canada-US relations, looks back at Canada-US defence policy, from the end of the Second World War and the creation of NATO and NORAD, to the end of the Cold War and the present realities of the post 9/11 world. While he regards BMD “as a high-tech Maginot Line,” he also writes that once the US “decided to proceed with BMD we should have supported it.” Depuis le discours de Franklin Roosevelt prononcé en 1938 à Queen’s University, le principe de défense mutuelle du Canada et des États-Unis est au cœur de notre politique étrangère et de défense. À de rares exceptions près, notamment lorsque John Diefenbaker a manqué à sa promesse d’accepter les missiles nucléaires Bomarc en 1963, ce principe a été reconduit par tous les gouvernements depuis celui de Mackenzie King dans les années 1940. Aussi peut-on considérer que Paul Martin a rompu avec la tradition en refusant sa participation à la défense antimissile balistique (DMB). -

An Exploration of the Subjective Experience Of

THE MEDIATED SELF: AN EXPLORATION OF THE SUBJECTIVE EXPERIENCE OF MASS MEDIA CELEBRlTY FANSHIP Michelie Louise Gibson B.F.A., University of British Columbia, 1979 M.A., University of British Columbia, 1993 A THESIS SUBMITIED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILSOPHY under Speciai Arrangements in the Faculty of Arts O Michelle Louise Gibson 2000 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 2000 Al1 rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Natio~lLibrary Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KiA ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bïbliotheque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriibute or seli reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni fa thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT While there are a sibstantial number of mass media fans in North America, limited research has been conducted on this population. -

The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: Exploring the Sovereignty Question

CHC2D1 The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: Exploring the Sovereignty Question Eight Lessons on Historical Thinking Concepts: Evidence, Significance, Perspective, Ethical Issues, Continuity and Change, and Cause and Consequence CURR335 Section 002 November 15, 2013 Prepared for Professor Theodore Christou B.A.H., M.A., P.h.D Prepared by: Derek Ryan Lachine Queen’s University Lesson 1: Introductory Lesson The Quiet Revolution and the October Crisis: The Sovereignty Question “Vive le Quebec libre!” 1 Class 1. Overview This lesson will ask students to ponder the meaning of separatism and engage with source material to understand how “Vive le Quebec libre” would have been perceived during the Quiet Revolution. This lesson will introduce the students to important people, terms, and ideas that will aid them in assessing how the separatist movement blossomed during the 60s, and what it meant in the eventual blow-up that would be the October Crisis of 1970. 2. Learning Goal To hypothesiZe how separatism can be viewed from an Anglo-Canadian and French- Canadian perspective. Demonstrate what line of thought your understanding and/or definition of separatism falls under: the Anglo, the French or the fence. Express educated hypotheses as to why French-Canadians would have found solidarity in Charles de Gaulle’s words, “Vive le Quebec libre”. 3. Curriculum Expectations a) A1.5- use the concepts of historical thinking (i.e., historical significance, cause and consequence, continuity and change, and historical perspective) when analyZing, evaluating evidence about, and formulating conclusions and/or judgements regarding historical issues, events, and/or developments in Canada since 1914 b) Introductory lesson: engage with preliminary ideas of separatism and how different regions of Canada show different perspectives towards Quebec nationalism.