Canada's Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George HW Bush and CHIREP at the UN 1970-1971

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971 James W. Weber Jr. University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weber, James W. Jr., "The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2756. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Cut is the Deepest : George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970–1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by James W. -

Download (PDF)

N° 3/2019 recherches & documents March 2019 Disarmament diplomacy Motivations and objectives of the main actors in nuclear disarmament EMMANUELLE MAITRE, research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-490100-19-4 EAN : 9782490100194 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1 – A CONVERGENCE OF PACIFIST AND HUMANITARIAN TRADITIONS ....................................... 8 1.1 – Neutrality, non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament .......................... 8 1.1.1 – Disarmament in the neutralist tradition .............................................................. 8 1.1.2 – Nuclear disarmament in a pacifist perspective .................................................. 9 1.1.1 – "Good international citizen" ..............................................................................11 1.2 – An emphasis on humanitarian issues ...............................................................13 1.2.1 – An example of policy in favor of humanitarian law ............................................13 1.2.2 – Moral, ethics and religion .................................................................................14 -

A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993

Canadian Military History Volume 24 Issue 2 Article 8 2015 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 Greg Donaghy Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Greg Donaghy "A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993." Canadian Military History 24, 2 (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canadian Military History by an authorized editor of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. : A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 A Calculus of Interest Canadian Peacekeeping Diplomacy in Cyprus, 1963-1993 GREG DONAGHY Abstract: Fifty years ago, Canadian peacekeepers landed on the small Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where they stayed for thirty long years. This paper uses declassified cabinet papers and diplomatic records to tackle three key questions about this mission: why did Canadians ever go to distant Cyprus? Why did they stay for so long? And why did they leave when they did? The answers situate Canada’s commitment to Cypress against the country’s broader postwar project to preserve world order in an era marked by the collapse of the European empires and the brutal wars in Algeria and Vietnam. It argues that Canada stayed— through fifty-nine troop rotations, 29,000 troops, and twenty-eight dead— because peacekeeping worked. Admittedly there were critics, including Prime Ministers Pearson, Trudeau, and Mulroney, who complained about the failure of peacemaking in Cyprus itself. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

R=Nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- R.104TA (-{, 001

3Kcnen~lHrn 3 . ~ ,_ CCCP r=nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- r.104TA (-{, 001 diasporiana.org.ua CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON CANADIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS Unive~ty Partnership Centre I Georgian College, Barrie, ON Vol. 9 I Canada/Russia Series J.L. Black ef Andrew Donskov, general editors CRCR One-Way Ticket The Soviet Return-to-the-Homeland Campaign, 1955-1960 Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko Penumbra Press I Manotick, ON I 2008 ,l(apyHoK OmmascbKozo siooiny KaHaOCbKozo Tosapucmsa npuHmeniB YKpai°HU Copyright © 2008 Library and Archives Canada SERGE CIPKO & GLENNA ROBERTS Cataloguing-in-Publication Data No part of this publication may be Roberts, Glenna, 1934- reproduced, stored in a retrieval system Cipko, Serge, 1961- or transmitted, in any1'0rm or by any means, without the prior written One-way ticket: the Soviet return-to consent of the publisher or a licence the-homeland campaign, 1955-1960 I from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko. Agency (Access Copyright). (Canada/Russia series ; no. 9) PENUMBRA PRESS, publishers Co-published by Centre for Research Box 940 I Manotick, ON I Canada on Canadian-Russian Relations, K4M lAB I penumbrapress.ca Carleton University. Printed and bound by Custom Printers, Includes bibliographical references Renfrew, ON, Canada. and index. PENUMBRA PRESS gratefully acknowledges ISBN 978-1-897323-12-0 the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing L Canadians-Soviet Union Industry Development Program (BPIDP) History-2oth century. for our publishing activities. We also 2. Repatriation-Soviet Union acknowledge the Government of Ontario History-2oth century. through the Ontario Media Development 3. Canadians-Soviet Union Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative. -

Conspiracy of Peace: the Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956

The London School of Economics and Political Science Conspiracy of Peace: The Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956 Vladimir Dobrenko A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 90,957 words. Statement of conjoint work I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by John Clifton of www.proofreading247.co.uk/ I have followed the Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition, for referencing. 2 Abstract This thesis deals with the Soviet Union’s Peace Campaign during the first decade of the Cold War as it sought to establish the Iron Curtain. The thesis focuses on the primary institutions engaged in the Peace Campaign: the World Peace Council and the Soviet Peace Committee. -

The Rhetoric of Trade and the Pragmatism of Policy: Canadian and New Zealand Commercial Relations with Britain, 1920-1950 Francine Mckenzie [email protected]

Western University Scholarship@Western History Publications History Department 2010 The Rhetoric of Trade and the Pragmatism of Policy: Canadian and New Zealand Commercial Relations with Britain, 1920-1950 Francine McKenzie [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/historypub Part of the History Commons Citation of this paper: McKenzie, Francine, "The Rhetoric of Trade and the Pragmatism of Policy: Canadian and New Zealand Commercial Relations with Britain, 1920-1950" (2010). History Publications. 390. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/historypub/390 THE RHETORIC OF TRADE AND THE PRAGMATISM OF POLICY: CANADIAN AND NEW ZEALAND COMMERCIAL RELATIONS WITH BRITAIN, 1920-1950 Francine McKenzie Department of History The University of Western Ontario INTRODUCTION In April 1948 Prime Minister Mackenzie King pulled Canada out of secret free trade negotiations with the United States. Although many officials in the Department of External Affairs believed that a continental free trade agreement was in Canada’s best interests, King confided to his diary that he could not let the negotiations go forward because a successful outcome would destroy the British Empire and Commonwealth: ‘I am sure in so doing, I have made one of the most important decisions for Canada, for the British Commonwealth of Nations that has been made at any time.’1 In October 1949, while being fêted in London, Prime Minister Sydney Holland of New Zealand, made one of his characteristic spontaneous and ill considered statements. He declared, ‘I want the people of Britain to know that we will send all the food that they need, even if we have to send it free’.2 These two stories tell historians a lot. -

PART III.—REGISTER of OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* the Following List Includes Official Appointments for the Period Sept

1164 MISCELLANEOUS DATA PART III.—REGISTER OF OFFICIAL APPOINTMENTS* The following list includes official appointments for the period Sept. 1, 1962 to Nov. 15, 1963, continuing the list published in the 1962 Year Book at pp. 1176-1181. Appointments to the Governor General's staff, judicial appointments other than those to the Supreme Court of Canada, and appointments of limited or local importance are not included. Queen's Privy Council for Canada.—1962. Oct. 15, Mark Robert Drouin, Sillery, Que.; and Roland Michener, Toronto, Ont.: to be members. Dec. 21, Rt. Hon. John George Diefenbaker, Prime Minister of Canada: to be President. 1963. Feb. 12, Marcel- Joseph-Aime Lambert, Edmonton, Alta.: to be a member. Feb. 20, Major-General Georges P. Vanier, Governor General of Canada: to be a member. Mar. 18, J.-H. Theogene Ricard, St. Hyacinthe, Que.; Frank Charles McGee, Don Mills, Ont.; and Martial Asselin, La Malbaie, Que.: to be members. Apr. 22, Walter Lockhart Gordon, Toronto, Ont.; Mitchell Sharp, Toronto, Ont.; Azellus Denis, Montreal, Que.; George James Mcllraith, Ottawa, Ont.; William Moore Benidickson, Kenora, Ont.; Arthur Laing, Vancouver, B.C.; John Richard Garland, North Bay, Ont.; Lucien Cardin, Sorel, Que.; Allan Joseph Mac- Eachen, Inverness, N.S.; Jean-Paul Deschatelets, Montreal, Que.; Hedard Robichaud, Caraquet, N.B.; J. Watson MacNaught, Summerside, P.E.I.; Roger Teillet, St. Boniface, Man.; Miss Judy LaMarsh, Niagara Falls, Ont.; Charles Mills Drury, Westmount, Que.; Guy Favreau, Montreal, Que.; John Robert Nicholson, Vancouver, B.C.; Harry Hays, Calgary, Alta.; Rene Tremblay, Quebec, Que.; and Maurice Lamontagne, Montreal, Que.: to be members, Maurice Lamontagne to be also President. -

Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: the Current State of R&D

COMPETING IN A GLOBAL INNOVATION ECONOMY: THE CURRENT STATE OF R&D IN CANADA Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada Science Advice in the Public Interest COMPETING IN A GLOBAL INNOVATION ECONOMY: THE CURRENT STATE OF R&D IN CANADA Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada ii Competing in a Global Innovation Economy: The Current State of R&D in Canada THE COUNCIL OF CANADIAN ACADEMIES 180 Elgin Street, Suite 1401, Ottawa, ON, Canada K2P 2K3 Notice: The project that is the subject of this report was undertaken with the approval of the Board of Directors of the Council of Canadian Academies (CCA). Board members are drawn from the Royal Society of Canada (RSC), the Canadian Academy of Engineering (CAE), and the Canadian Academy of Health Sciences (CAHS), as well as from the general public. The members of the expert panel responsible for the report were selected by the CCA for their special competencies and with regard for appropriate balance. This report was prepared for the Government of Canada in response to a request from the Minister of Science. Any opinions, findings, or conclusions expressed in this publication are those of the authors, the Expert Panel on the State of Science and Technology and Industrial Research and Development in Canada, and do not necessarily represent the views of their organizations of affiliation or employment, or the sponsoring organization, Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Council of Canadian Academies. -

Canada's Antidumping and Safeguard Policies: Overt and Subtle Forms Of

Revised version forthcoming in The World Economy Canada’s Antidumping and Safeguard Policies: Overt and Subtle Forms of Discrimination Chad P. Bown† Brandeis University & The Brookings Institution This Draft: February 2007 (Original draft: April 2005) Abstract Like many countries in the international trading system, Canada repeatedly faces political pressure from industries seeking protection from import competition. I examine Canadian policymakers’ response to this pressure within the economic environment created by its participation in discriminatory trade agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). In particular, I exploit new sources of data on Canada’s use of potentially WTO-consistent import-restricting policies such as antidumping, global safeguards, and a China-specific safeguard. I illustrate subtle ways in which Canadian policymakers may be structuring the application of such policies so as to reinforce the discrimination inherent in Canada’s external trade policy because of the preferences granted to the United States and Mexico through NAFTA. JEL No. F13 Keywords: Canada, trade policy, antidumping, safeguards, MFN, WTO † Correspondence: Department of Economics and International Business School, MS 021, Brandeis University, PO Box 549110, Waltham, MA, 02454-9110 USA. tel: 781-736-4823, fax: 781-736-2269, email: [email protected], web: http://www.brandeis.edu/~cbown/. I gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Centre for International Governance Innovation. I thank Rachel McCulloch for comments -

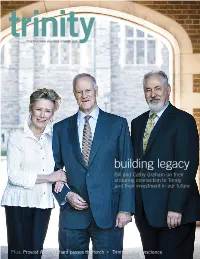

Building Legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on Their Enduring Connection to Trinity and Their Investment in Our Future

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch • Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply flies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or five years of living and learning and growing and gaining fined the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long after the place itself has been left behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire office. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Office friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Affairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long after Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

Department of State Key Officers List

United States Department of State Telephone Directory This customized report includes the following section(s): Key Officers List (UNCLASSIFIED) 1/17/2017 Provided by Global Information Services, A/GIS Cover UNCLASSIFIED Key Officers of Foreign Service Posts Afghanistan RSO Jan Hiemstra AID Catherine Johnson CLO Kimberly Augsburger KABUL (E) Great Massoud Road, (VoIP, US-based) 301-490-1042, Fax No working Fax, INMARSAT Tel 011-873-761-837-725, ECON Jeffrey Bowan Workweek: Saturday - Thursday 0800-1630, Website: EEO Erica Hall kabul.usembassy.gov FMO David Hilburg IMO Meredith Hiemstra Officer Name IPO Terrence Andrews DCM OMS vacant ISO Darrin Erwin AMB OMS Alma Pratt ISSO Darrin Erwin Co-CLO Hope Williams DCM/CHG Dennis W. Hearne FM Paul Schaefer Algeria HRO Dawn Scott INL John McNamara ALGIERS (E) 5, Chemin Cheikh Bachir Ibrahimi, +213 (770) 08- MGT Robert Needham 2000, Fax +213 (21) 60-7335, Workweek: Sun - Thurs 08:00-17:00, MLO/ODC COL John Beattie Website: http://algiers.usembassy.gov POL/MIL John C. Taylor Officer Name SDO/DATT COL Christian Griggs DCM OMS Sharon Rogers, TDY TREAS Tazeem Pasha AMB OMS Carolyn Murphy US REP OMS Jennifer Clemente Co-CLO Julie Baldwin AMB P. Michael McKinley FCS Nathan Seifert CG Jeffrey Lodinsky FM James Alden DCM vacant HRO Dana Al-Ebrahim PAO Terry Davidson ICITAP Darrel Hart GSO William McClure MGT Kim D'Auria-Vazira RSO Carlos Matus MLO/ODC MAJ Steve Alverson AFSA Pending OPDAT Robert Huie AID Herbie Smith POL/ECON Junaid Jay Munir CLO Anita Kainth POL/MIL Eric Plues DEA Craig M.