And the Cold War, 1945-1970”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

George HW Bush and CHIREP at the UN 1970-1971

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-22-2020 The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971 James W. Weber Jr. University of New Orleans, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Part of the American Popular Culture Commons, Asian History Commons, Cultural History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Weber, James W. Jr., "The First Cut is the Deepest: George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970-1971" (2020). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 2756. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/2756 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The First Cut is the Deepest : George H.W. Bush and CHIREP at the U.N. 1970–1971 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History by James W. -

Photo Gallery

Cover Illustration The new Central Government Offices on the harbourfront are designed as an ‘open door’ to depict the administration as open and receptive to new ideas. The offices, which opened in August, are part of a major project at Tamar that houses the Legislative Council Complex and the Chief Executive’s Office and features an abundance of greenery and open space. End-paper Maps Front Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Back Hong Kong and Pearl River Delta Satellite Image Map Events in 2011 This year’s major events included a visit to Hong Kong in August by the Vice-Premier of the State Council, Mr Li Keqiang, pictured, delivering the keynote address at the Forum on the National 12th Five-Year Plan and Economic, Trade and Financial Co-operation and Development between the Mainland and Hong Kong at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre. Other major events included visits by foreign dignitaries as well as overseas visits by senior Hong Kong officials – and Guinness World Records. Events in 2011 Top left: The then Chief Secretary for Administration, Mr Henry Tang, calls on Singapore Prime Minister, Mr Lee Hsien Loong, during his trip to the island state in February. Above left: The Chief Secretary for Administration, Mr Stephen Lam, meets the German Federal Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr Guido Westerwelle, in Berlin in October. Above right: The Chief Executive, Mr Donald Tsang (first row, first right), poses with other world leaders at the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation Economic Leaders’ Meeting in Honolulu in November. Right: The Chief Executive welcomes the US Secretary of State, Mrs Hillary Rodham Clinton, at Government House in Hong Kong on July 25. -

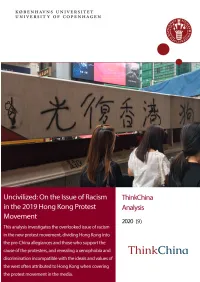

Uncivilized: on the Issue of Racism in the 2019 Hong Kong Protest Movement

This ThinkChina analysis is written by Mai Corlin, Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Fine Arts, Chinese University of Hong Kong. Editor(s): Casper Wichmann and Silke Hult Lykkedatter. Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this ThinkChina publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of ThinkChina. Copyright of this publication is held by ThinkChina. You may not copy, reproduce, republish or circulate in any way the content from this publication without acknowledgement of ThinkChina as the source, except for your own personal and non-commercial use. Any other use requires the prior written permission of ThinkChina or the author(s). ©ThinkChina and the author(s) 2020 Front page picture: Photograph by Mai Corlin. Caption: Graffiti drawn during a demonstration in the Hong Kong district of Mongkok. Winnie the Pooh (left) is a reference to Xi Jinping. The Chinese characters read the first part of the well-known slogan attributed Hong Kong activist and localist, Edward Leung: “Liberate Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Time (光復香港, 時代革命 ).” ThinkChina, University of Copenhagen Karen Blixens Vej 4 2300 Copenhagen S Mail: [email protected] Web: www.thinkchina.dk ThinkChina Analysis 2020 Uncivilized: On the Issue of Racism in the 2019 Hong Kong Protest Movement Mai Corlin: Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Fine Arts, Chinese University of Hong Kong Since the introduction of an extradition bill in April 2019, which in some cases would have allowed extradition to mainland China, a new wave of civil unrest arose, and in June 2019, the streets of Hong Kong were once again flooded by public demonstrations – a new protest movement, not completely unlike the ‘Umbrella Movement’ for democracy in 2014. -

Conspiracy of Peace: the Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956

The London School of Economics and Political Science Conspiracy of Peace: The Cold War, the International Peace Movement, and the Soviet Peace Campaign, 1946-1956 Vladimir Dobrenko A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, October 2015 Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 90,957 words. Statement of conjoint work I can confirm that my thesis was copy edited for conventions of language, spelling and grammar by John Clifton of www.proofreading247.co.uk/ I have followed the Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition, for referencing. 2 Abstract This thesis deals with the Soviet Union’s Peace Campaign during the first decade of the Cold War as it sought to establish the Iron Curtain. The thesis focuses on the primary institutions engaged in the Peace Campaign: the World Peace Council and the Soviet Peace Committee. -

Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY An Jingfu (1994) The Pain of a Half Taoist: Taoist Principles, Chinese Landscape Painting, and King of the Children . In Linda C. Ehrlich and David Desser (eds.). Cinematic Landscapes: Observations on the Visual Arts and Cinema of China and Japan . Austin: University of Texas Press, 117–25. Anderson, Marston (1990) The Limits of Realism: Chinese Fiction in the Revolutionary Period . Berkeley: University of California Press. Anon (1937) “Yueyu pian zhengming yundong” [“Jyutpin zingming wandung” or Cantonese fi lm rectifi cation movement]. Lingxing [ Ling Sing ] 7, no. 15 (June 27, 1937): no page. Appelo, Tim (2014) ‘Wong Kar Wai Says His 108-Minute “The Grandmaster” Is Not “A Watered-Down Version”’, The Hollywood Reporter (6 January), http:// www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/wong-kar-wai-says-his-668633 . Aristotle (1996) Poetics , trans. Malcolm Heath (London: Penguin Books). Arroyo, José (2000) Introduction by José Arroyo (ed.) Action/Spectacle: A Sight and Sound Reader (London: BFI Publishing), vii-xv. Astruc, Alexandre (2009) ‘The Birth of a New Avant-Garde: La Caméra-Stylo ’ in Peter Graham with Ginette Vincendeau (eds.) The French New Wave: Critical Landmarks (London: BFI and Palgrave Macmillan), 31–7. Bao, Weihong (2015) Fiery Cinema: The Emergence of an Affective Medium in China, 1915–1945 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press). Barthes, Roland (1968a) Elements of Semiology (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1968b) Writing Degree Zero (trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith). New York: Hill and Wang. Barthes, Roland (1972) Mythologies (trans. Annette Lavers), New York: Hill and Wang. © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2016 203 G. -

How to Deal with Russia (Cultural Internationalism Rather Than Territorial Dispute)

How To Deal With Russia (Cultural Internationalism Rather Than Territorial Dispute) Hideaki Kinoshita Introduction Considering relations with Russia, it appears to be imperative among the Japanese people to raise the question of the Northern Territories, which comprises the islands of Habomai, Shikotan, Kunashiri and Etorofu. It is because the issue is perceived by the Japanese people as the apparent act of unprovoked aggression initiated during the final stages of World War II by Russian’s illegal and perfidious attack on the Chishima Islands with a sudden shift from relations of friendship to enmity. Japan was actually courting the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics(USSR) to perform as an intermediary for the armistice with the Allied Forces. Russian’s sudden attack unilaterally abrogating the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact concluded in April, 1941 was baffling for the Japanese government, and aroused the impression to the Japanese that they were duped to the committing to the agreement. The agreement specified mutual respect of territorial integrity and inviolability as well as neutrality should one of the contracting parties become the object of hostilities of any third party(Slavinsky 1996: 129). The Soviet attack no doubt was executed within the validity period of the pact and after the Japanese notification of accepting the Potsdam Declaration on August 15, 1945, and even continued after concluding the armistice on the Battleship Missouri on September 2, 1945(Iokibe, Hatano 2015: 311). The concept, advocated by the government, of “inherent” Japanese Northern Territories helped foment the idea of the so called “residual” legal rights to the four islands in the Japanese public psyche. -

Thematic Unit Template

Chinese World Grade Level: Grade Two Unit Theme: Countries/Cities/Geography Ohio Standards Connection: Foreign Language Standard: Communication: Communicate in languages other than English. Benchmark A: Ask and answer questions and share preferences on familiar topics. Indicator 1: Ask and answer questions about likes and dislikes (e.g., What is your favorite color?/¿Cuál es tu color favorite? What fruit don’t you like?/Welche Frucht hast du nicht gern?). Benchmark H: Identify the main idea and describe characters and setting in oral, signed or written narratives. Indicator 9: Answer simple questions concerning essential elements of a story (e.g., who? what? when? where? how?). Benchmark K: Present information orally, signed or in writing. Indicator 15: Label familiar objects or people (e.g., school supplies, family members, geometric shapes) and share with others. Benchmark L: Apply age-appropriate writing process strategies to write short, guided paragraphs on various topics. Indicator 16: Apply age-appropriate writing process strategies (prewriting, drafting, revising, editing, publishing) to simple sentences. Standard: Cultures: Gain knowledge and understanding of other cultures. Benchmark A: Observe, identify and describe simple patterns of behavior of the target culture. Indicator 1: Identify appropriate patterns of behavior (e.g., gestures used with friends and family). Benchmark B: Identify and imitate gestures and oral expressions to participate in age- appropriate cultural activities. Indicator 3: Sing/sign songs, play games and celebrate events from the target culture. Benchmark C: Observe, identify, describe and reproduce objects, images and symbols of the target culture. 1 Indicator 4: Make a tangible cultural product (e.g., a craft, toy, food, flag). -

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane

Google Overview Created by Phil Wane PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Tue, 30 Nov 2010 15:03:55 UTC Contents Articles Google 1 Criticism of Google 20 AdWords 33 AdSense 39 List of Google products 44 Blogger (service) 60 Google Earth 64 YouTube 85 Web search engine 99 User:Moonglum/ITEC30011 105 References Article Sources and Contributors 106 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 112 Article Licenses License 114 Google 1 Google [1] [2] Type Public (NASDAQ: GOOG , FWB: GGQ1 ) Industry Internet, Computer software [3] [4] Founded Menlo Park, California (September 4, 1998) Founder(s) Sergey M. Brin Lawrence E. Page Headquarters 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, California, United States Area served Worldwide Key people Eric E. Schmidt (Chairman & CEO) Sergey M. Brin (Technology President) Lawrence E. Page (Products President) Products See list of Google products. [5] [6] Revenue US$23.651 billion (2009) [5] [6] Operating income US$8.312 billion (2009) [5] [6] Profit US$6.520 billion (2009) [5] [6] Total assets US$40.497 billion (2009) [6] Total equity US$36.004 billion (2009) [7] Employees 23,331 (2010) Subsidiaries YouTube, DoubleClick, On2 Technologies, GrandCentral, Picnik, Aardvark, AdMob [8] Website Google.com Google Inc. is a multinational public corporation invested in Internet search, cloud computing, and advertising technologies. Google hosts and develops a number of Internet-based services and products,[9] and generates profit primarily from advertising through its AdWords program.[5] [10] The company was founded by Larry Page and Sergey Brin, often dubbed the "Google Guys",[11] [12] [13] while the two were attending Stanford University as Ph.D. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan the UNIVERSITY of OKLAHOMA

This dissertation has been 64-126 microfilmed exactly as received SOH, Jin ChuU, 1930- SOME CAUSES OF THE KOREAN WAR OF 1950; A CASE STUDY OF SOVIET FOREIGN POLICY IN KOREA (1945-1950), WITH EMPHASIS ON SINO- SOVIET COLLABORATION. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D., 1963 Political Science, international law and relations University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA. GRADUATE COLLEGE SOME CAUSES OF THE KOREAN WAR OF 1950: A CASE STUDY OF SOVIET FOREIGN POLICY IN KOREA (1945-1950), WITH EMPHASIS ON SING-SOVIET COLLABORATION A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY JIN CHULL SOH Norman, Oklahoma 1963 SOME CAUSES OF THE KOREAN WAR OF I95 O: A CASE STUDY OF SOVIET FOREIGN POLICY IN KOREA (1945-1950), WITH EMPHASIS ON SINO-SOVIET COLLABORATION APPROVED BY DISSERTATION COMMITTEE ACKNOWLEDGMENT The writer chose this subject because the Commuaist strategy in Korea is a valuable case study of an instance in which the "cold war" became exceedingly hot. Many men died and many more were wounded in a conflict which could have been avoided if the free world had not been ignorant of the ways of the Communists. Today, many years after the armored spearhead of Communism first drove across the 38th parallel, 350 ,0 0 0 men are still standing ready to repell that same enemy. It is hoped that this study will throw light on the errors which grew to war so that they might not be repeated at another time in a different place. -

Canada's Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Canada’s Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia: An Assessment of the Trudeau Government’s First International Crisis by Angus McCabe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Angus McCabe ii Abstract The new government of Pierre Trudeau was faced with an international crisis when, on 20 August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. This study is the first full account of the Canadian government’s response based on an examination of the archival records of the Departments of External Affairs, National Defence, Manpower and Immigration, and the Privy Council Office. Underlying the government’s reaction were differences of opinion about Canada’s approach to the Cold War, its role at the United Nations and in NATO, the utility of the Department of External Affairs, and decisions about refugees. There was a delusory quality to each of these perspectives. In the end, an inexperienced government failed to heed some of the more competent advice it received concerning how best to meet Canada’s interests during the crisis. National interest was an understandable objective, but in this case, it was pursued at Czechoslovakia’s expense. iii Acknowledgements As anyone in my position would attest, meaningful work with Professor Norman Hillmer brings with it the added gift of friendship. The quality of his teaching, mentorship, and advice is, I suspect, the stuff of ages. I am grateful for the privilege of his guidance and comradeship. Graduate Administrator Joan White works kindly and tirelessly behind the scenes of Carleton University’s Department of History. -

TWENTY-EIGHTH YEAR Th MEETING: 6

TWENTY-EIGHTH YEAR th MEETING: 6 JUNE 1973 NEW YORK CONTENTS Page Provisional agenda (S/Agenda/l7 17) . , . * * . , . 9 . 1 Expression of thanks to the retiring President . * . , . 1 Adoption of the agenda , . , . .,.... 1 The situation in the Middle East: [a) Security Council resolution 33 1 (I 973); fb) Report of the Secretary-General under Security Council resolution 331 (1973) (S/10929) . I . , I * . * . * * . *. 1 SlPV.1717 NOTE Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. Documents of the Security Council (symbol S/. .) are normally published in quarterly Supplements of the Official Records of the Security Council. The date of the document indicates the supplement in which it appears or in which information about it is given. The resolutions of the Security Council, numbered in accordance with a system adopted in 1964, are published in yearly volumes of Resolutions and Decisions of the Security Council. The new system, which has been applied retroactively to resolutions adopted before 1 January 1965, became fully operative on that date. SEVENTEEN HUNDRED AND SEVENTEENTH MEETING Held in New York on Wednesday, 6 June 1973, at 10.30 a.m. President: Mr. Yakov MALIK ‘The situation in the Middle East: (Union of Soviet Socialist Republics). (a) Security Council resolution 331 (1973); (6) Report of the Secretary-General under Security PLesenf: The representatives of the following States: Council resolution 331 (1973) (S/10929) Australia, Austria, China, France, Guinea, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Panama, Peru, Sudan, Union of Soviet Socialist 2. -

Open Dissertation FINAL2.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of Communications AFTER A RAINY DAY IN HONG KONG: MEDIA, MEMORY AND SOCIAL MOVEMENTS, A LOOK AT HONG KONG’S 2014 UMBRELLA MOVEMENT A Dissertation in Mass Communications by Kelly A. Chernin © 2017 Kelly A. Chernin Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2017 The dissertation of Kelly A. Chernin was reviewed and approved* by the following: Matthew F. Jordan Associate Professor of Media Studies Dissertation Adviser Chair of Committee C. Michael Elavsky Associate Professor of Media Studies Michelle Rodino-Colocino Associate Professor of Media Studies Stephen H. Browne Liberal Arts Research Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Ford Risley Professor of Communications Associate Dean of the College of Communications *Signatures are on file in the graduate school. ii ABSTRACT The period following an occupied social movement is often overlooked, yet it is an important moment in time as political and economic systems are potentially vulnerable. In 2014, after Hong Kong’s Chief Executive declared that the citizens of Hong Kong would be unable to democratically elect their leader in the upcoming 2017 election, a 79-day occupation of major city centers ensued. The memory of the three-month occupation, also known as the Umbrella Movement was instrumental in shaping a political identity for Hong Kong’s residents. Understanding social movements as a process and not a singular event, an analytic mode that problematizes linear temporal constructions, can help us move beyond the deterministic and celebratory views often associated with technology’s role in social movement activism.