Download Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tai Chi Sword DR

TAI CHI CHUAN / MARTIAL ARTS B2856 BESTSELLING AUTHOR OF BOOKS AND VIDEOS ON TAI CHI, MARTIAL ARTS, AND QIGONG Tai Chi Sword Chi Sword Tai DR. YANG, JWING-MING REACH FOR THE HIGHEST LEVEL OF TAI CHI PRACTICE You can achieve the highest level of tai chi practice by including tai chi sword in your training regimen. Here’s your chance to take the next step in your tai chi journey Once you have attained proficiency in the bare-hand form, and have gained listening and sensing skills from pushing hands, you are ready for tai chi sword. Tai Chi Sword The elegant and effective techniques of traditional tai chi sword CLASSICAL YANG STYLE Tai chi sword will help you control your qi, refine your tai chi skills, and master yourself. You will strengthen and relax your body, calm and focus your mind, THE COMPLETE FORM, QIGONG, AND APPLICATIONS improve your balance, and develop proper tai chi breathing. This book provides a solid and practical approach to learning tai chi sword Style Classical Yang One of the people who have “made the accurately and quickly. Includes over 500 photographs with motion arrows! greatest impact on martial arts in the • Historical overview of tai chi sword past 100 years.” • Fundamentals including hand forms and footwork —Inside Kung Fu • Generating power with the sword 傳 Magazine • 12 tai chi sword breathing exercises • 30 key tai chi sword techniques with applications • 12 fundamental tai chi sword solo drills 統 • Complete 54-movement Yang Tai Chi Sword sequence • 48 martial applications from the tai chi sword sequence DR. -

Afa M Footbl__2006Footballme

TTaabbllee ooff CCoonntteennttss This is Air Force Football 2005 Results Defensive Records . 122-123 Note from Fisher DeBerry . 1 Season Statistics . 88-90 All-Time Letterwinners . 124-128 Game Day at Falcon Stadium. 2-3 Team/Individual Highs . 91 Past Season Results. 129-133 Air Force Football Traditions . 4-5 Player career highs . 92 Post-Season Recaps . 134-137 Commander-in-Chief’s Trophy. 6-7 Misc. Statistics . 93-94 Bowl Quick Facts . 137 Bullard Award. 8-9 Game-by-Game Statistics . 95-96 Bowl Records . 138 Falcons in the Pros . 10 2005 Game Recaps . 97-100 Air Force Academy fast facts . 11 Media Table of Contents . 12 Mountain West Conference Covering Air Force . 140 MWC Story. 102 Future Schedules. 140 Academy CSTV . 103 Media Guidelines . 141 The Air Force Academy . 14 2006 Composite Schedule . 104 Local Media Outlets . 142 Academy Senior Leadership. 15 2005 Team Statistics . 105 Academy Map / Directions. 143 Athletic Administration. 16 2005 Individual Statistics . 106 Note pad . 144 Academy Athletics . 17 Falcon Mascot. 18 History Falcon Stadium . 19 All-Americans. 108 Sports Medicine . 20-21 All-Conference Honorees . 109 Pagentry of Air Force Football. 22-23 All-American Profiles. 110-113 Falcon Athletic Center . 24 All-Star Games . 113 Rushing Records. 114-115 Coaches Passing Records . 116-117 Fisher DeBerry . 26-29 Total Offense Records . 118 Richard Bell . 30 Kicking Records . 119 Ron Burton . 31 Scoring Records . 120 Dean Campbell . 32 Receiving Records . 121 Dick Enga . 33 Paul Hamilton . 34 Pete Hurt . 35 Credits Brian Knorr. 36 The 2006 Air Force Football Media Guide is a product of the Academy’s Athletic Tom Miller . -

Songs by Title Karaoke Night with the Patman

Songs By Title Karaoke Night with the Patman Title Versions Title Versions 10 Years 3 Libras Wasteland SC Perfect Circle SI 10,000 Maniacs 3 Of Hearts Because The Night SC Love Is Enough SC Candy Everybody Wants DK 30 Seconds To Mars More Than This SC Kill SC These Are The Days SC 311 Trouble Me SC All Mixed Up SC 100 Proof Aged In Soul Don't Tread On Me SC Somebody's Been Sleeping SC Down SC 10CC Love Song SC I'm Not In Love DK You Wouldn't Believe SC Things We Do For Love SC 38 Special 112 Back Where You Belong SI Come See Me SC Caught Up In You SC Dance With Me SC Hold On Loosely AH It's Over Now SC If I'd Been The One SC Only You SC Rockin' Onto The Night SC Peaches And Cream SC Second Chance SC U Already Know SC Teacher, Teacher SC 12 Gauge Wild Eyed Southern Boys SC Dunkie Butt SC 3LW 1910 Fruitgum Co. No More (Baby I'm A Do Right) SC 1, 2, 3 Redlight SC 3T Simon Says DK Anything SC 1975 Tease Me SC The Sound SI 4 Non Blondes 2 Live Crew What's Up DK Doo Wah Diddy SC 4 P.M. Me So Horny SC Lay Down Your Love SC We Want Some Pussy SC Sukiyaki DK 2 Pac 4 Runner California Love (Original Version) SC Ripples SC Changes SC That Was Him SC Thugz Mansion SC 42nd Street 20 Fingers 42nd Street Song SC Short Dick Man SC We're In The Money SC 3 Doors Down 5 Seconds Of Summer Away From The Sun SC Amnesia SI Be Like That SC She Looks So Perfect SI Behind Those Eyes SC 5 Stairsteps Duck & Run SC Ooh Child SC Here By Me CB 50 Cent Here Without You CB Disco Inferno SC Kryptonite SC If I Can't SC Let Me Go SC In Da Club HT Live For Today SC P.I.M.P. -

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY of ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University Ofhong Kong

The Globalization of Chinese Food ANTHROPOLOGY OF ASIA SERIES Series Editor: Grant Evans, University ofHong Kong Asia today is one ofthe most dynamic regions ofthe world. The previously predominant image of 'timeless peasants' has given way to the image of fast-paced business people, mass consumerism and high-rise urban conglomerations. Yet much discourse remains entrenched in the polarities of 'East vs. West', 'Tradition vs. Change'. This series hopes to provide a forum for anthropological studies which break with such polarities. It will publish titles dealing with cosmopolitanism, cultural identity, representa tions, arts and performance. The complexities of urban Asia, its elites, its political rituals, and its families will also be explored. Dangerous Blood, Refined Souls Death Rituals among the Chinese in Singapore Tong Chee Kiong Folk Art Potters ofJapan Beyond an Anthropology of Aesthetics Brian Moeran Hong Kong The Anthropology of a Chinese Metropolis Edited by Grant Evans and Maria Tam Anthropology and Colonialism in Asia and Oceania Jan van Bremen and Akitoshi Shimizu Japanese Bosses, Chinese Workers Power and Control in a Hong Kong Megastore WOng Heung wah The Legend ofthe Golden Boat Regulation, Trade and Traders in the Borderlands of Laos, Thailand, China and Burma Andrew walker Cultural Crisis and Social Memory Politics of the Past in the Thai World Edited by Shigeharu Tanabe and Charles R Keyes The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung The Globalization of Chinese Food Edited by David Y. H. Wu and Sidney C. H. Cheung UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I PRESS HONOLULU Editorial Matter © 2002 David Y. -

Warriors As the Feminised Other

Warriors as the Feminised Other The study of male heroes in Chinese action cinema from 2000 to 2009 A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Chinese Studies at the University of Canterbury by Yunxiang Chen University of Canterbury 2011 i Abstract ―Flowery boys‖ (花样少年) – when this phrase is applied to attractive young men it is now often considered as a compliment. This research sets out to study the feminisation phenomena in the representation of warriors in Chinese language films from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Mainland China made in the first decade of the new millennium (2000-2009), as these three regions are now often packaged together as a pan-unity of the Chinese cultural realm. The foci of this study are on the investigations of the warriors as the feminised Other from two aspects: their bodies as spectacles and the manifestation of feminine characteristics in the male warriors. This study aims to detect what lies underneath the beautiful masquerade of the warriors as the Other through comprehensive analyses of the representations of feminised warriors and comparison with their female counterparts. It aims to test the hypothesis that gender identities are inventory categories transformed by and with changing historical context. Simultaneously, it is a project to study how Chinese traditional values and postmodern metrosexual culture interacted to formulate Chinese contemporary masculinity. It is also a project to search for a cultural nationalism presented in these films with the examination of gender politics hidden in these feminisation phenomena. With Laura Mulvey‘s theory of the gaze as a starting point, this research reconsiders the power relationship between the viewing subject and the spectacle to study the possibility of multiple gaze as well as the power of spectacle. -

Clifford Modern Living Holdings Limited 祈福

THIS CIRCULAR IS IMPORTANT AND REQUIRES YOUR IMMEDIATE ATTENTION If you are in any doubt as to any aspect of this circular or as to the action to be taken, you should consult a stockbroker or other licensed securities dealer, bank manager, solicitor, professional accountant or other professional advisers. If you have sold or transferred all your shares in Clifford Modern Living Holdings Limited 祈福生活服務控股 有限公司, you should at once hand this circular and the accompanying form of proxy to the purchaser(s) or the transferee(s) or to the bank, stockbroker or licensed securities dealer or other agent through whom the sale or transfer was effected for transmission to the purchaser(s) or the transferee(s). Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this circular, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this circular. CLIFFORD MODERN LIVING HOLDINGS LIMITED 祈福生活服務控股有限公司 (Incorporated in the Cayman Islands with limited liability) (Stock Code: 3686) CONTINUING CONNECTED TRANSACTIONS: RESPECTIVE SUPPLEMENTAL AGREEMENTS TO THE MASTER TENANCY AGREEMENT AND THE MASTER COMPOSITE SERVICES AGREEMENT AND REVISION OF ANNUAL CAPS Independent Financial Adviser to the Independent Board Committee and the Independent Shareholders A letter from the Board is set out on pages 6 to 19 of this circular. A letter from the Independent Board Committee containing its recommendation to the Independent Shareholders is set out on pages 20 to 21 of this circular. -

Hong Kong at a Glance: 2001-02

COUNTRY REPORT Hong Kong At a glance: 2001-02 OVERVIEW Donald Tsang will take over as chief secretary for administration on May 1st; he will be succeeded as financial secretary by Antony Leung. The first term in office of the chief executive, Tung Chee-hwa, comes to an end in 2002. He is unpopular in Hong Kong, but trusted by China's government, and so is likely to be appointed to a second term. After growing by 10.5% in 2000, real GDP is likely to expand by just 3% in 2001 as external demand weakens. Growth will pick up to 3.9% in 2002 on the back of improving export performance. Consumer prices are likely to be broadly stable this year, but inflation will return in 2002. The current account is likely to remain in modest surplus this year and next, despite an expanding merchandise trade deficit. Key changes from last month Political outlook • The government introduced legislation in mid-March that will enable the selection of the next chief executive to be made by the same 800-person election committee that was chosen in July 2000 for the purpose of selecting legislators in the Legco election the following September. This reinforces the EIU's view that Tung Chee-hwa will be re-appointed to a new term. Economic policy outlook • Interest rates have continued to fall, in line with reductions by the US Federal Reserve. We expect US rates to fall by a further 100 basis points this year, compared with our previous forecast of reductions of 75 basis points. -

Congratulations to Wudang San Feng Pai!

LIFE / HEALTH & FITNESS / FITNESS & EXERCISE Congratulations to Wudang San Feng Pai! February 11, 2013 8:35 PM MST View all 5 photos Master Zhou Xuan Yun (left) presented Dr. Ming Poon (right) Wudang San Feng Pai related material for a permanent display at the Library of Congress. Zhou Xuan Yun On Feb. 1, 2013, the Library of Congress of the United States hosted an event to receive Wudang San Feng Pai. This event included a speech by Taoist (Daoist) priest and Wudang San Feng Pai Master Zhou Xuan Yun and the presentation of important Wudang historical documents and artifacts for a permanent display at the Library. Wudang Wellness Re-established in recent decades, Wudang San Feng Pai is an organization in China, which researches, preserves, teaches and promotes Wudang Kung Fu, which was said originally created by the 13th century Taoist Monk Zhang San Feng. Some believe that Zhang San Feng created Tai Chi (Taiji) Chuan (boxing) by observing the fight between a crane and a snake. Zhang was a hermit and lived in the Wudang Mountains to develop his profound philosophy on Taoism (Daoism), internal martial arts and internal alchemy. The Wudang Mountains are the mecca of Taoism and its temples are protected as one of 730 registered World Heritage sites of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). Wudang Kung Fu encompasses a wide range of bare-hand forms of Tai Chi, Xingyi and Bagua as well as weapon forms for health and self-defense purposes. Traditionally, it was taught to Taoist priests only. It was prohibited to practice during the Chinese Cultural Revolution (1966- 1976). -

Chen Village (陈家沟 Chén Jiā Gōu) This Is the Birthplace of All Taijiquan

Chen Village (陈家沟 Chén Jiā Gōu) This is the birthplace of all Taijiquan (Tai Chi) as we know it today. If Chen Wangting is the 9th generation founder of Taijiquan, it is astounding and noteworthy to know that direct descendants of the 11th generation still live and teach in the same village. This historical place has many legendary Taijiquan masters such as Yang Luchan and Chen Fake. Chen Village is located in central China-- Henan Province, Wenxian County. Taijiquan Schools in Chenjiagou 1.Chen Bing Taiji Academy Headquarters Established in 2008 by Master Chen Bing after he became independent from the Chenjiagou Taijiquan School. He was a former vice president and headcoach at the Chenjiagou Taijiquan School. Due to Grandmaster Chen Xiaoxing’s careful consideration, Master Chen Bing was able to take over an original property passed on to an eldest son. It used to be Grandmaster Chen Xiaoxing’s house right next to the graveyard of 18th generation Chen Zhaopi. [email protected] www.ChenBing.org 323 – 735 – 0672 2.Chenjiagou Taijiquan School Chenjiagou Taijiquan School is located in Chenjiagou, Wenxian, Henan Province, China. Since 1979, the school has developed and grown to become a world famous martial arts school. These changes were by masters from the original Chen family. These include Honorary President Chen Xiaowang, President Chen Xiaoxing and Vice President Chen Ziqiang. Master Chen Bing was a former vice president and head coach of this school from 1991 – 2007 before he independently opened his school in 2008. [email protected] www.ChenBing.org 323 – 735 – 0672 3. -

A Complete Tai Chi Weapon System

LIFE / HEALTH & FITNESS / FITNESS & EXERCISE Recommended: a complete Tai Chi weapon system December 7, 2014 7:35 PM MST There are five major Tai Chi (Taiji) styles; Chen style is the origin. Chen Style Tai Chi has the most complete weapon system, which includes Single Straight Sword, Double Straight Sword, Single Broad Sword (Saber), Double Broad Sword, Spear, Guan Dao (Halberd), Long Pole, and Double Mace (Baton). Recently Master Jack Yan translated and published Grandmaster Chen Zhenglei’s detailed instructions on all eight different weapons plus Push Hands to English in two different volumes. View all 19 photos Chen Zhenglei Culture Jack Yan Grandmaster Chen is a 19th Generation Chen Family descendent and 11th Generation Chen Style Tai Chi Lineage Holder. He is sanctioned as the 9th Duan by the Chinese Martial Art Association the highest level in martial arts. He was selected as one of the Top Ten Martial Art Masters in China for his superb Tai Chi skills and in-depth knowledge. He has authored a complete set of books on Chen Style Tai Chi bare-hand and weapons forms. Master Jack Yan translated three other volumes on bare-hand forms. With these two new additions, all of Grandmaster Chen’s writings are accessible in English. Each of the Chen weapons has its features. Straight swords, sabers, and batons are short weapons while long pole, halberd, and spear are long weapons. Volume Four is for short weapons while Volume Five is for long weapons and Push Hands. Chen Style Single Straight Sword is one of the oldest weapon routines with forty-nine movements, tightly connected with specific and clear sword techniques, namely pierce, chop, upward-swing, hook, point, slice, lift, upward-block, sweep, cut, jab, push, and neutralize. -

Representantes-22.OCT .14.Pdf

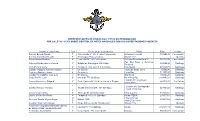

REPRESENTANTES DE DISCIPLINAS Y ESTILOS RECONOCIDOS POR LA LEY Nº 18.356 SOBRE CONTROL DE ARTES MARCIALES CON SUS ACREDITACIONES VIGENTES Nombres y Apellidos Dan Dirección de la academia Estilo Fono Ciudad Alarcón Belmar Oscar 7° Calle Heras N° 813 2° piso Concepción. Defensa Personal 74760436 Concepción Barrera Arancibia Ricardo 8° Aconcagua 752 La Calera. Shaolin Tse Quillota Bruna Urrutia Rodrigo 4° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. Defensa Personal Israelí 56373506 Concepción Pak Mei Kune y Defensa Cabrera Maldonado Hortensia 7° Batalla de Rancagua 539 Maipú. 88550636 Santiago Personal Caro Pizarro Víctor 5° Tarapacá 1324 local 3 A Santiago. Krav Maga 98528875 Santiago Catalán Vásquez Alberto Mauricio 4° En trámite. Taijiquan Estilo Chen 6890530 Santiago Cavieres Martínez Jorge 6° En trámite. Hung Gar 71377097 Santiago Candia Hormazabal José Luis 5° En trámite. Wai Kung 78696520 Santiago Colipí Curiñir Juan 6° Morandé 771 Santiago. Nam Hwa Pai 2-6880123 Santiago Hapkido Cheong Kyum Correa Manríquez Edgard 5° Calle Carrera N° 1624 La Calera V Región. 94171533 La Calera Association. 5° - Choson Mu Sul Hapkido Cubillos Alarcón Richard Vicuña Mackenna N° 227 Santiago. 22472122 Santiago - Pekiti Tirsia Kali 4° Collao Vega Carlos 6° Alameda N° 2489 Santiago Choy Lay Fut 73333201 Santiago Daiber Vuillemín Alberto 4° Tarapacá 777(779) Santiago. Aikikai-FEPAI 29131087 Santiago 9° - Tsung Chiao De Luca Garate Miguel Angel Bilbao 1559 98221052 Santiago 5° - Hung Gar Kuen Escobar Silva Luis Antonio 7° Diego Echeverría N° 786 Quillota. Shaolin Tao Quillota Federación Deportiva Nacional Chilena 6° Libertad N° 86 Santiago. Aikikai 2-6817703 Santiago de Aikido Aikikai (FEDENACHAA) Fernández Soria Mario 5° Castellón N° 292 Concepción. -

Chapter 2 Chinese Martial Arts

Chapter 2 Chinese Martial Arts My adult life has been defined by the practice of traditional Chi- nese body technologies, a long-term practical research project I began on Richard Fowler’s suggestion. From September 1993 to September 2005 I studied cailifoquan (Cantonese: choy li fut kuen), a martial art from Southern China; tang peng taijiquan (Cantonese: tong ping taigek kuen), a Northern Chinese martial art; and zhi neng qigong, a contemporary body technology designed to develop the student’s health and longevity, with Wong Sui Meing in Montréal. Since I started in 1993 I estimate I have completed at least 10,000 hours of training under Wong’s direct supervision. Figure 8: The author’s teacher Wong Sui Meing in his Montréal studio, Wong Kung Fu. (Photo by Daniel Mroz) 46 The Dancing Word In September of 2005 I began to study chen taiji shiyong quanfa, a very old form of taijiquan, under the instruction of Chen Zhonghua. I participated in a series of intensive workshops and private lessons over a two-year period and in May 2007 traveled to Daqingshan Mountain in Shandong Province, China, for a one-month full-time intensive training period. I continue to study privately with Chen as often as his busy international teaching schedule allows. In August 2007 Chen granted me a formal teaching license in the style. In addition to these long-term studies, I have cross-trained in a variety of other styles of martial movement, including Indian kalarip- payattu under the late Govindankutty Nair (d. 2006), Indonesian kun- tao and silat under Willem deThouars and his senior student Randall Goodwin and Chinese baguazhang with Ken Cohen and Allen Pittman.