An Exploration of the Subjective Experience Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

Canada Day As Part of a Political Master Brand

Celebrating the True North: Canada Day as part of a political master brand Justin Prno Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Department of Communication Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Justin Prno, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH ii Abstract In Canada, the rise of political branding coincided with the adoption of the permanent campaign, creating an environment in which politicking is now normalized and politicization is expected. With Canada Day 2017 as a case study, this thesis adopts Marland’s Branding Lens Thesis (2016) as a conceptual framework to analyze if a national holiday became part of the Liberal Party of Canada’s master brand. The key conclusion of this thesis is that the Liberals integrated their ‘master brand’ into Canada Day 2017 by integrating political branding into their government communications. This thesis also shows that Justin Trudeau played a bigger role during Canada Day than expected by a Prime Minister. Significantly, this thesis shows the Liberal government altered the themes and messaging of Canada 150 to parallel that of their master brand, applying a Liberal tint to Canada Day and Canada 150. CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH iii Acknowledgements I’ve been known to talk a lot, but when it comes to the written word, I often come up short. Either way here goes... I would like to thank the community of people that surround me, near and far, past and present. Having you as part of my life makes taking these trips around the sun far more enjoyable. -

Creation's Lab the Next Frontier in The

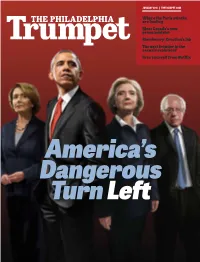

JANUARY 2016 | THETRUMPET.COM Where the Paris attacks are leading Meet Canada’s new prime minister Biomimicry: Creation’s lab The next frontier in the sexual revolution? Free yourself from Netflix America’s Dangerous Turn Left JANUARY 2016 VOL. 27, NO. 1 CIRC. 287,157 NIGHT OF TERROR A tarp covers one of the victims of the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris. (GETTY IMAGES) COVER GARY DORNING/TRUMPET Cover Story Features Unriddling the Radical Worldview From the Editor of President Obama 2 Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading 1 The Roots of America’s Dangerous Like Father, Like Son? 11 Turn Left 6 Canada’s democratic system has empowered a dynasty Why Educators Are Attracted to Communism 9 that’s not big on democracy. Justin Trudeau’s Vision for Canada 31 Fear This Man 12 It is dangerous to underestimate Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Departments Will Putin Reignite the Balkans? 14 Worldwatch Pressure on Merkel, admiration for Europe’s next crisis could hit in what used to be Yugoslavia. Hitler?, Putin—savior of Russians, etc. 26 How Europe Conquered the Balkans 16 Societywatch Record gun-sales, etc. 29 Infographic: Biomimicry—Learning From Creation 18 Principles of Living Your Glorious, God-Given Power 33 The Next Frontier in the Sexual Revolution? 20 Discussion Board 34 Free Yourself From Netflix 22 Commentary Teaching the Unteachable 35 Will the Two Chinas Become One? 23 The Key of David Television Log 36 The time when Taiwan will be swallowed is approaching. More Trumpet Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Trumpet executive editor Stephen News and analysis A weekly digest Flurry’s weekly television program Flurry’s television program updated daily of important news theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpet_daily theTrumpet.com theTrumpet.com/trumpetweekly From the Editor Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading Most people are focusing on France’s reaction—but the ultimate aftereffect will consume all of Europe. -

AFFECTIVE PRACTICES of NATION and NATIONALISM on CANADIAN TELEVISION by MARUSYA BOCIURKIW BFA, Nova Scotia C

I FEEL CANADIAN: AFFECTIVE PRACTICES OF NATION AND NATIONALISM ON CANADIAN TELEVISION by MARUSYA BOCIURKIW B.F.A., Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, 1982 M.A., York University, 1999 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA October 2004 © Marusya Bociurkiw 2004 -11 - ABSTRACT In this dissertation, I examine how ideas about the nation are produced via affect, especially Canadian television's role in this discursive construction. I analyze Canadian television as a surface of emergence for nationalist sentiment. Within this commercial medium, U.S. dominance, Quebec separatism, and the immigrant are set in an oppositional relationship to Canadian nationalism. Working together, certain institutions such as the law and the corporation, exercise authority through what I call 'technologies of affect': speech-acts, music, editing. I argue that the instability of Canadian identity is re-stabilized by a hyperbolic affective mode that is frequently produced through consumerism. Delimited within a fairly narrow timeframe (1995 -2002), the dissertation's chronological starting point is the Quebec Referendum of October 1995. It concludes at another site of national and international trauma: media coverage of September 11, 2001 and its aftermath. Moving from traumatic point to traumatic point, this dissertation focuses on moments in televised Canadian history that ruptured, or tried to resolve, the imagined community of nation, and the idea of a national self and national others. I examine television as a marker of an affective Canadian national space, one that promises an idea of 'home'. -

Nixonian Foreign Policy and the Changing Canadian American Relationship

Not With a Bang but a Whimper: Nixonian Foreign Policy and the Changing Canadian American Relationship By Robyn Schwarz Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the History Honours Program in History University of British Columbia, Okanagan 2012 Faculty Supervisor: Dr. Doug Owram, DVC and Department of History Author’s Signature: ___________________________ Date: _______________ Supervisor’s Signature: ___________________________ Date: _______________ Honours Chair’s Signature: ___________________________ Date: _______________ ii © Robyn Schwarz 2012 iii Abstract An examination of Richard Nixon’s foreign policy and the way it contributed to changing the Canadian-American relationship from 1969-1974. Nixon’s administration redirected U.S. foreign policy, as outlined in the Nixon Doctrine, to address American interests under the influence of the Vietnam War. In doing so, the Nixon administration ignored issues linked to Canada such as trade and economics. Pierre Elliot Trudeau was also repositioning Canada’s international priorities during this period. The Nixon Economic Shock created a gap between the two countries. Canadians felt betrayed by the American decision to impose an import surcharge on their goods. Looking at documented meetings of the two leaders also reveals that both men did not cooperate well with one another. The Canadian-American relationship was permanently altered during this period because of a combination of these different factors. iv Acknowledgements I would first like to extend a thank you to my supervisor, Dr. Doug Owram, without whom I could not have completed this project. He has been a great asset in my writing despite his busy schedule. I appreciate the interest he has taken in my work and his direction has been invaluable. -

The Year 1968—Some Claiming Objectivity and Others Stating Their Prejudices—I Am Convinced That Fairness Is Possible but True Objectivity Is Not

file:///D|/Temp%2093/1968/1968.htm file:///D|/Temp%2093/1968/1968.htm (1 of 350)04.04.2006 16:28:44 file:///D|/Temp%2093/1968/1968.htm "Splendid . evocative ... No one before Kurlansky has managed to evoke so rich a set of experiences in so many different places—and to keep the story humming." -Chicago Tribune To some, 1968 was the year of sex, drugs, and rock and roll. Yet it was also the year of the Martin Luther King, Jr., and Bobby Kennedy assassinations; the riots at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago; Prague Spring; the antiwar movement and the Tet Offensive; Black Power; the generation gap; avant-garde theater; the upsurge of the women's movement; and the beginning of the end for the Soviet Union. In this monumental book, Mark Kurlansky brings to teeming life the cultural and political history of that pivotal year, when television's influence on global events first became apparent, and spontaneous uprisings occurred simultaneously around the world. Encompassing the diverse realms of youth and music, politics and war, economics and the media, 1968 shows how twelve volatile months transformed who we were as a people—and led us to where we are today. "A cornucopia of astounding events and audacious originality ... Like a reissue of a classic album or a PBS documentary, this book is about a subject it's hard to imagine people ever tiring of revisiting. They just don't make years like 1968 very often." - The Atlanta Journal-Chronicle "Fascinating ... [Kurlansky] re-creates events with flair and drama." - Seattle Post-Intelligencer "Highly readable .. -

Pierre Elliott Trudeau and His Influence on Canadian Politics

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English Language and Literature Vojtěch Ulrich Pierre Elliott Trudeau and His Influence on Canadian Politics Bachelor’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Kateřina Prajznerová, Ph.D. 2010 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature 2 I would like to thank Mgr. Kateřina Prajznerová, Ph.D. for her kind help and valuable suggestions throughout the writing of this thesis. 3 Table of Contents 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………..5 2. Trudeau’s Personality and Public Image...................................................................7 2.1. Trudeau‟s Public Appeal………………………………………………………….7 2.2. Events Which Influenced Trudeau‟s Popularity……………………………….....9 2.3. Trudeaumania…………………………………………………………………...10 2.4. Problems with Inappropriate Behaviour………………………………………...12 3. Trudeau and Quebec……………………………………………………………….15 3.1. Nationalism in Quebec………………………………………………………….15 3.2. Language Issues…………….…………………………………………………...17 3.3. October Crisis…………………………………………………………………...19 3.4. Democratic Attempts at Separation……………………………………………..22 3.5. Constitutional Reform…………………………………………………………..24 4. Trudeau and Canada’s Foreign Relations………………………………………...26 4.1. Trudeau‟s Early Life and Its Impact on His Views on International Politics…...26 4.2. Trudeau‟s Approach to International Politics and Canada as a Middle Power….28 4.3. International Summits…………………………………………………………...30 -

Pierre Trudeau: Captivating a Nation

Pierre Trudeau: Captivating a Nation Introduction Contents On an overcast October morning in Montreal, thousands of people made their way to Notre- Dame Basilica to witness the state funeral of a major Canadian political figure. Former prime Introduction minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau had died a few days before at the age of 80. In the weeks prior to his death, Trudeau's failing health had been public knowledge; nonetheless, his death had Witnessing History a profound effect on the collective psyche of the nation. Trudeau had resigned as prime minister in 1984, and in the succeeding years had kept a fairly low profile, interrupted only by his forceful interventions in the debates over the Meech Lake and Charlottetown constitutional For the Record accords. An entire generation of young Canadians had been born and grown to near adulthood after he left the public stage. Canada had changed much, and four prime ministers The Trudeau Legacy had assumed the office since his resignation. However, the unprecedented grief and sorrow over his death was a clear indication of the profound and enduring although often A Personal Reflection ambivalentfeelings of Canadians toward this remarkable man. Trudeau's funeral in Montreal was itself an event of considerable historic importance. From all Discussion, Research and parts of Canada and the world, both friends and political foes came to pay tribute. Joe Clark, Essay Question who had battled Trudeau in years past and now found himself back in Parliament once more as Conservative leader, expressed his warm personal regards for his old rival. Premier Lucien Bouchard, whose goal of a sovereign Quebec was an idea Trudeau had unfalteringly resisted throughout his life, spoke eloquently of the former prime minister's service to the francophones of that province. -

Michigan Journal of International Affairs April 2016

Michigan Journal of International Affairs April 2016 LETTER FROM THE EDITORIAL BOARD he past year has revealed leaders with uniquely firm grasps over their po- T litical spheres in all corners of the world. In this edition of the Michigan Jour- nal of International Affairs, we therefore take special note of individuals who loom large over their respective countries – defining fig- ures with national influence of international consequence. Interestingly, the rising promi- nence of strongmen and consolidated power on a global scale is not necessarily a reason for concern. As a number of our writers express in this issue, the presence of indispensable power-players is not the end of world affairs as we know it, but rather another chapter in the long history of singular power shaping the international system. In The Cycle Continues, Laura Vicinanza argues that Latin America is stuck in an endless loop of populism and predicts the rightward swing of the region’s governments. Vicinanza notes the emergence of a new genera- tion of leaders who no longer resemble the populist leaders of decades past. Regional Editor Emma Stout discusses the impending change in leader- ship in Angola in Changing Power in Angola. She contends that the Angolan presidency is likely to pass from father to son, an often undemocratic move by national leaders. She explains, however, that this is the country’s best option, regardless of charges of nepotism, due to allegations of corruption against the other chief candidate. Nick Serra writes in Italy and Eurozone Reform that Italian Prime Min- ister Mateo Renzi’s zeal, enthusiasm, and willingness to make unpopular decisions is often met with skepticism from his European Union counter- parts. -

The Trudeau Era: Major Events

cbc.ca/archives CBC Radio and Television Archives Web Site Educational Activities Download Sheet Name: Date: The Trudeau Era: Major Events Project Outline Description: Begin research using the following topics on the CBC Radio and Television Archives Web site: The Berger Pipeline Inquiry, Trudeaumania: A Swinger for Prime Minister, The October Crisis: Civil Liberties Suspended, and Canada's Constitutional Debates, then expand your search to include other resources. Use your research to prepare and present a newspaper or broadcast newsmagazine dealing with one of the following topics related to the Trudeau era: Trudeaumania, the October Crisis, Canada's Constitutional Debates, and the Berger Pipeline Inquiry. Purpose: 1. To research information using Internet and traditional sources 2. To successfully complete basic research on a given topic 3. To prepare and present a newspaper or broadcast newsmagazine Timelines: Start date: _________________ Due date: _________________ Procedures: 1. Project is introduced in class. 2. In your group, choose a format for your presentation. 3. In your group, research the information you will need for your presentation. 4. Gather your information and prepare a rough draft of your newspaper or broadcast newsmagazine for peer or teacher evaluation. 5. Make necessary revisions based on peer or teacher evaluation. 6. Complete or rehearse a final version of your presentation. 7. Present your newspaper or broadcast newsmagazine to the class. 8. Finished presentation is evaluated. Assessment: In this chart, list or follow the specific evaluation criteria determined by your teacher. Criteria Description/Explanation Mark/Percentage Value © CBC cbc.ca/archives CBC Radio and Television Archives Web Site Educational Activities Download Sheet Name: Date: Major Events of the Trudeau Era Use this worksheet to help focus your research on the following events of the Trudeau Era: Trudeaumania, The October Crisis, The Constitutional Debate, and the Berger Pipeline Inquiry. -

Pierre Trudeau's Just Society

PIERRE TRUDEAU’S JUST SOCIETY: BOLD ASPIRATIONS MEET REALITIES OF GOVERNING A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts in History University of Regina By Jason Michael Chestney Regina, Saskatchewan September 2018 Copyright 2018: J. Chestney UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Jason Michael Chestney, candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in History, has presented a thesis titled, Pierre Trudeau’s Just Society: Bold Aspirations Meets Realities of Governing, in an oral examination held on September 7, 2018. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: Dr. Ken Rasmussen, Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School Supervisor: Dr. Raymond Blake, Department of History Committee Member: Dr. Donica Belisle, Department of History Committee Member: Dr. Ken Leyton-Brown, Department of History Chair of Defense: Dr. Eldon Soifer, Department of Philosophy & Classics UNIVERSITY OF REGINA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES AND RESEARCH SUPERVISORY AND EXAMINING COMMITTEE Jason Michael Chestney, candidate for the degree of Master of Arts in History, has presented a thesis titled, Pierre Trudeau’s Just Society: Bold Aspirations Meets Realities of Governing, in an oral examination held on September 7, 2018. The following committee members have found the thesis acceptable in form and content, and that the candidate demonstrated satisfactory knowledge of the subject material. External Examiner: Dr. Ken Rasmussen, Johnson-Shoyama Graduate School Supervisor: Dr. Raymond Blake, Department of History Committee Member: Dr. -

Trudeau Through the Looking Glass

Trudeau Through the Looking Glass David Tough Books explains his success as a politician. A thinker with such an explicit and uncompromising agenda is a B. W. Powe Mystic Trudeau: The Fire and the Rose. less–than–likely object of a cult of personality, but Thomas Allen Publishers, 2007, 256 pages Trudeau, as everyone knows, was swept to power in 1968 on a tide of hysterical popular support. Clearly, George Elliott Clarke Trudeau: Long March and as Ramsay Cook has noted recently, misrecognition Shining Path. Gaspereau Press, 2007, 123 pages played a large part in the frenzy. “Among his 1968 supporters,” Cook says in his 2006 memoir, The “If you want to talk about symbols, I’m not even Teeth of Time: Remembering Pierre Elliott Trudeau, going to bother talking to you!” “I had met young Quebec nationalists, far–left – Pierre Trudeau to René Lévesque, 1963 NDPers, and, most frequently, journalists and even Liberal politicians whose understanding of Trudeau’s I ONCE HEARD an impishly provocative philosophy antinationalist federalist philosophy and commitment professor suggest to his undergraduate students that to bilingualism was founded on little more than a few Friedrich Nietzsche’s writing is like a mirror: it hastily read newspaper articles. … It was only a reflects readers back to themselves, in all their matter of time before disillusionment set in among unique, unspeakable horror. The point of this sly those whose image of Trudeau was constructed from provocation, of course, was to short–circuit all the personal imagination and yearning.” Yes, there complaints that Nietzsche is really a fascist, a certainly was disillusionment as Trudeau’s actions misogynist, a postmodernist – anything, really, other failed to jibe with the characteristics his admirers than someone who wrote.