Pierre Elliott Trudeau and His Influence on Canadian Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

Étude De Deux Conflits De Travail Au

UNIVERSrrE DU QuEBEC AMONTREAL LE DlSCOURS GOUVERNEMENTAL ET LA LEGITIMITE DU DROIT ALA NEGOCIATION COLLECTIVE: ETUDE DE DEUX CON FLITS DE TRAVAIL AU QuEBEC MENANT AL'ADOPTION DE LOIS FOR<;ANT LE RETOUR AU TRAVAIL MEMOlRE PRESENTE COMME mCIGENCE PARTIELLE DE LA MAlTRISE EN DROIT DU TRAVAlL PAR MARIE-EVE BERNIER NOVEMBRE 2007 UNIVERSITE DU QUEBEC AMONTREAL Service des bibliotheques Avertissement La diffusion de ce rnernolre se fait dans Ie respect des droits de son auteur, qui a siqne Ie formulaire Autorisation de reproduire et de diffuser un travail de recherche de cycles supetieurs (SDU-522 - Rev.01-2006). Cette autorisation stipule que «contorrnernent a I'article 11 du Reglement no 8 des etudes de cycles superieurs, [I'auteur] concede a l'Universite du Quebec a Montreal une licence non exclusive d'utilisation et de publication de la totalite ou d'une partie importante de [son] travail de recherche pour des fins pedaqoqiques et non commerciales. Plus precisernent, [I'auteur] autorise l'Universlte du Quebec a Montreal a reproduire , diffuser, preter, distribuer ou vendre des copies de [son] travail de recherche a des fins non commerciales sur quelque support que ce soit, y compris l'lnternet. Cette licence et cette autorisation n'entrainent pas une renonciation de ria] part [de I'auteur] a [ses] droits moraux ni a [ses] droits de propriete intellectuelle. Sauf entente contraire , [I'auteu r] conserve la liberte de diffuser et de commercial iser ou non ce travail dont [il] possede un exernplaire .» Note au lecteur: L'auteure tient it souligner que Ies donnees juridiques contenues dans ce memoire sont it jour it Ia fin du mois d'avril 2007. -

L'entreprise De Presse Et Le Journaliste

PRESSES DE L’UNIVERSITÉ DU QUÉBEC 2875, boul. Laurier, Sainte-Foy (Québec) G1V 2M3 Téléphone : (418) 657-4399 Télécopieur : (418) 657-2096 Catalogue sur Internet : http://www.uquebec.ca/puq Distribution : DISTRIBUTION DE LIVRES UNIVERS S.E.N.C. 845, rue Marie-Victorin, Saint-Nicolas (Québec) G7A 3S8 Téléphone : (418) 831-7474 / 1-800-859-7474 Télécopieur : (418) 831-4021 La Loi sur le droit d’auteur interdit la reproduction des oeuvres sans autorisation des titulaires de droits. Or, la photocopie non autorisée – le « photocopillage » – s’est généralisée, provoquant une baisse des ventes de livres et compromettant la rédaction et la production de nouveaux ouvrages par des professionnels. L’objet du logo apparaissant ci-contre est d’alerter le lecteur sur la menace que représente pour l’avenir de l’écrit le développement massif du « photocopillage ». AURÉLIEN LECLERC avec la collaboration de Jacques Guay Ouvrage conçu et édité sous la responsabilité du Cégep de Jonquière, avec la collaboration du ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Science. Données de catalogage avant publication (Canada) Leclerc, Aurélien L’entreprise de presse et le journaliste Comprend des références bibliographiques : p. ISBN 2-7605-0615-0 1. Presse. 2. Journalisme. 3. Entreprise de presse. 4. Journalisme – Art d’écrire. I. Titre. PN4775.L42 1991 070.4 C91-096993-0 Les Presses de l’Université du Québec remercient le Conseil des arts du Canada et le Programme d’aide au développement de l’industrie de l’édition du Patrimoine canadien pour l’aide accordée à leur programme de publication. La Direction générale de l’enseignement collégial du ministère de l’Enseignement supérieur et de la Science a apporté un soutien pédagogique et financier à la réalisation de cet ouvrage. -

A Tapestry of Peoples

HIGH SCHOOL LEVEL TEACHING RESOURCE FOR THE PROMISE OF CANADA, BY CHARLOTTE GRAY Author’s Note Greetings, educators! While I was in my twenties I spent a year teaching in a high school in England; it was the hardest job I’ve ever done. So first, I want to thank you for doing one of the most important and challenging jobs in our society. And I particularly want to thank you for introducing your students to Canadian history, as they embark on their own futures, because it will help them understand how our past is what makes this country unique. When I sat down to write The Promise of Canada, I knew I wanted to engage my readers in the personalities and dramas of the past 150 years. Most of us find it much easier to learn about ideas and values through the stories of the individuals that promoted them. Most of us enjoy history more if we are given the tools to understand what it was like back then—back when women didn’t have the vote, or back when Indigenous children were dragged off to residential schools, or back when Quebecers felt so excluded that some of them wanted their own independent country. I wanted my readers to feel the texture of history—the sounds, sights and smells of our predecessors’ lives. If your students have looked at my book, I hope they will begin to understand how the past is not dead: it has shaped the Canada we live in today. I hope they will be excited to meet vivid personalities who, in their own day, contributed to a country that has never stopped evolving. -

07.SSG9 Cluster4:Cluster 4.Qxd

Canada in the Contemporary World GRADE 9 Canada: Opportunities and Challenges 4 CLUSTER Cluster 4 Learning Experiences: Canada: Opportunities Overview GRADE and Challenges 9 4 CLUSTER 9.4.1 A Changing Nation KL-026 Analyze current Canadian demographics and predict future trends. KH-033 Give examples of social and technological changes that continue to influence quality of life in Canada. Examples: education, health care, social programs, communication, transportation... VH-010 Appreciate that knowledge of the past helps to understand the present and prepare for the future. 9.4.2 Engaging in the Citizenship Debate KC-014 Describe current issues related to citizenship in Canada. KC-015 Give examples of evolving challenges and opportunities in Canadian society as a result of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. KI-022 Analyze current issues surrounding Canadian culture and identity. VC-003 Be willing to engage in discussion and debate about citizenship. 9.4.3 Social Justice in Canada KI-023 Identify possible ways of resolving social injustices in Canada. KL-027 Give examples of opportunities and challenges related to First Nations treaties and Aboriginal rights. KE-052 Identify poverty issues in Canada and propose ideas for a more equitable society. Examples: homelessness, child poverty, health care, education, nutrition... VL-006 Respect traditional relationships that Aboriginal peoples of Canada have with the land. 9.4.4 Taking Our Place in the Global Village KL-028 Evaluate Canadian concerns and commitments regarding environmental stewardship and sustainability. KG-041 Give examples of contributions of various Canadians to the global community. Include: arts and science. KG-042 Describe Canada’s responsibilities and potential for leadership regarding current global issues. -

Canada Day As Part of a Political Master Brand

Celebrating the True North: Canada Day as part of a political master brand Justin Prno Thesis submitted to the University of Ottawa in partial Fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Department of Communication Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Justin Prno, Ottawa, Canada, 2019 CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH ii Abstract In Canada, the rise of political branding coincided with the adoption of the permanent campaign, creating an environment in which politicking is now normalized and politicization is expected. With Canada Day 2017 as a case study, this thesis adopts Marland’s Branding Lens Thesis (2016) as a conceptual framework to analyze if a national holiday became part of the Liberal Party of Canada’s master brand. The key conclusion of this thesis is that the Liberals integrated their ‘master brand’ into Canada Day 2017 by integrating political branding into their government communications. This thesis also shows that Justin Trudeau played a bigger role during Canada Day than expected by a Prime Minister. Significantly, this thesis shows the Liberal government altered the themes and messaging of Canada 150 to parallel that of their master brand, applying a Liberal tint to Canada Day and Canada 150. CELEBRATING THE TRUE NORTH iii Acknowledgements I’ve been known to talk a lot, but when it comes to the written word, I often come up short. Either way here goes... I would like to thank the community of people that surround me, near and far, past and present. Having you as part of my life makes taking these trips around the sun far more enjoyable. -

Démesures De Guerre

DÉMESURES DE GUERRE ABUS, IMPOSTURES ET VICTIMES D’OCTOBRE 1970 Sous la direction d’ANTHONY BEAUSÉJOUR Avec la collaboration de GUY BOUTHILLIER MATHIEU HARNOIS-BLOUIN MANON LEROUX IRAI nº XII CATHERINE PAQUETTE Étude 7 NORA T. LAMONTAGNE Octobre 2020 DANIEL TURP DÉMESURES DE GUERRE ABUS, IMPOSTURES ET VICTIMES D’OCTOBRE 1970 Démesures de guerre Abus, impostures et victimes d’Octobre 1970 Sous la direction d’Anthony Beauséjour Avec la collaboration de Guy Bouthillier Mathieu Harnois-Blouin Manon Leroux Catherine Paquette Nora T. Lamontagne Daniel Turp IRAI nº XII Étude 7 Octobre 2020 Édition : IRAI Recherche d’archives : Karine Perron / Madame Karine inc. Révision linguistique : Sophie Brisebois / C’est-à-dire inc. Conception et mise en page : Dany Larouche / infographie I-Dezign © Les auteurs, 2020 Tous droits réservés Photo de couverture : Des enfants curieux observent les forces militaires protégeant le poste de police de la rue Parthenais à Montréal, le 15 octobre 1970. / Curious children watch military forces protect the police station on Parthenais St. in Montreal, October 15, 1970. © : George Bird / The Montreal Star / Bibliothèque et Archives Canada / PA-129838 Institut de recherche sur l’autodétermination des peuples et les indépendances nationales www.irai.quebec [email protected] À propos de l’IRAI Fondé en 2016, l’IRAI est un institut de recherche indépendant et non partisan qui a pour mission de réaliser et de diffuser des travaux de recherche sur les enjeux relatifs aux thèmes de l’autodétermination des peuples et des indépendances nationales. L’IRAI vise ainsi à améliorer les connaissances scientifiques et à favoriser un dialogue citoyen ouvert et constructif autour de ces thèmes. -

Canadian Television Today

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2006 Canadian Television Today Beaty, Bart; Sullivan, Rebecca University of Calgary Press Beaty, B. & Sullivan, R. "Canadian Television Today". Series: Op/Position: Issues and Ideas series, No. 1. University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2006. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/49311 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com CANADIAN TELEVISION TODAY by Bart Beaty and Rebecca Sullivan ISBN 978-1-55238-674-3 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. -

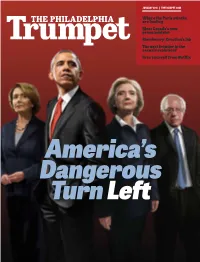

Creation's Lab the Next Frontier in The

JANUARY 2016 | THETRUMPET.COM Where the Paris attacks are leading Meet Canada’s new prime minister Biomimicry: Creation’s lab The next frontier in the sexual revolution? Free yourself from Netflix America’s Dangerous Turn Left JANUARY 2016 VOL. 27, NO. 1 CIRC. 287,157 NIGHT OF TERROR A tarp covers one of the victims of the November 13 terrorist attacks in Paris. (GETTY IMAGES) COVER GARY DORNING/TRUMPET Cover Story Features Unriddling the Radical Worldview From the Editor of President Obama 2 Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading 1 The Roots of America’s Dangerous Like Father, Like Son? 11 Turn Left 6 Canada’s democratic system has empowered a dynasty Why Educators Are Attracted to Communism 9 that’s not big on democracy. Justin Trudeau’s Vision for Canada 31 Fear This Man 12 It is dangerous to underestimate Russia’s Vladimir Putin. Departments Will Putin Reignite the Balkans? 14 Worldwatch Pressure on Merkel, admiration for Europe’s next crisis could hit in what used to be Yugoslavia. Hitler?, Putin—savior of Russians, etc. 26 How Europe Conquered the Balkans 16 Societywatch Record gun-sales, etc. 29 Infographic: Biomimicry—Learning From Creation 18 Principles of Living Your Glorious, God-Given Power 33 The Next Frontier in the Sexual Revolution? 20 Discussion Board 34 Free Yourself From Netflix 22 Commentary Teaching the Unteachable 35 Will the Two Chinas Become One? 23 The Key of David Television Log 36 The time when Taiwan will be swallowed is approaching. More Trumpet Trumpet editor in chief Gerald Trumpet executive editor Stephen News and analysis A weekly digest Flurry’s weekly television program Flurry’s television program updated daily of important news theTrumpet.com/keyofdavid theTrumpet.com/trumpet_daily theTrumpet.com theTrumpet.com/trumpetweekly From the Editor Where the Paris Attacks Are Leading Most people are focusing on France’s reaction—but the ultimate aftereffect will consume all of Europe. -

![Parliamentary Language Canada[Edit]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2077/parliamentary-language-canada-edit-1872077.webp)

Parliamentary Language Canada[Edit]

Parliamentary Language Parliaments and legislative bodies around the world impose certain rules and standards during debates. Tradition has evolved that there are words or phrases that are deemed inappropriate for use in the legislature whilst it is in session. In a Westminster system, this is called unparliamentary language and there are similar rules in other kinds of legislative system. This includes, but is not limited to the suggestion of dishonesty or the use of profanity. The most prohibited case is any suggestion that another member is dishonourable. So, for example, suggesting that another member is lying is forbidden.[1] Exactly what constitutes unparliamentary language is generally left to the discretion of the Speaker of the House. Part of the speaker's job is to enforce the assembly's debating rules, one of which is that members may not use "unparliamentary" language. That is, their words must not offend the dignity of the assembly. In addition, legislators in some places are protected from prosecution and civil actions by parliamentary immunitywhich generally stipulates that they cannot be sued or otherwise prosecuted for anything spoken in the legislature. Consequently they are expected to avoid using words or phrases that might be seen as abusing that immunity. Like other rules that have changed with the times, speakers' rulings on unparliamentary language reflect the tastes of the period. Canada[edit] These are some of the words and phrases that speakers through the years have ruled "unparliamentary" in the Parliament -

La Fondation Lionel-Groulx

FONDATION LIONEL-GROULX BIBLIOTHÈQUE DE LA FONDATION CATALOGUE DES LIVRES FC/2946.1/C132 14/1962 103094 Inscr. : / / M.à j. : 2010/10/21 ... Société historique de Québec. "Fier passé oblige", 1937-1962 / Société historique de Québec. -- Québec : La Société, Université Laval, 1962. 77 p.: ill. ; 23 cm. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- FC/2911/E85/1981 104831 Inscr. : 2003/01/22 M.à j. : 2010/10/07 ... "L'Étoffe du pays". -- [Québec] : Confédération des caisses populaires et d'économie Desjardins du Québec, 1981. 153 p. : ill. ; 21 cm. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- HM/479/L662 L695/2002 109072 Inscr. : 2005/02/03 M.à j. : 2010/10/26 ... "La liberté aussi vient de Dieu--" : témoignages en l'honneur de Georges-Henri Lévesque, O.P., (1903-2000) / sous la direction de Pierre Valcour et François Beaudin. [Sainte-Foy] : Presses de l'Université Laval, cop. 2002. 312 p., [15] p. de pl. : ill. (certaines en coul.), portr. (certains en coul.) ; 24 cm. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- D/810/W7 P624/1986 109879 Inscr. : 2006/01/11 M.à j. : 2010/09/02 Pierson, Ruth Roach, 1938- "They're still women after all" : the Second World War and Canadian womanhood / Ruth Roach Pierson. Toronto : McClelland and Stewart, c1986. 301 p. : ill. ; 21 cm. ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- F/1051/S143 F293/1963 103069 Inscr. : / / M.à j. : 2010/10/04 ... Fédération des sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste du Québec. "Vers un Québec fort" : la Société Saint-Jean-Baptiste (ce qu'elle est - ce qu'elle pense - ce qu'elle fait) ; cliniques données les 23 et 30 mars 1963 à l'occasion de la Semaine nationale S.S.J.B. / Fédération des sociétés Saint-Jean-Baptiste du Québec. -

The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left During the Long Sixties

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2019 1:00 PM 'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties David G. Blocker The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Fleming, Keith The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David G. Blocker 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Blocker, David G., "'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6554. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6554 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract The Sixties were time of conflict and change in Canada and beyond. Radical social movements and countercultures challenged the conservatism of the preceding decade, rejected traditional forms of politics, and demanded an alternative based on the principles of social justice, individual freedom and an end to oppression on all fronts. Yet in Canada a unique political movement emerged which embraced these principles but proposed that New Left social movements – the student and anti-war movements, the women’s liberation movement and Canadian nationalists – could bring about radical political change not only through street protests and sit-ins, but also through participation in electoral politics.