M.A. Thesis: Final Draft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jewish Journey in the Late Fiction of Aharon Appelfeld: Return, Repair Or Repitition?

The Jewish Journey in the Late fiction of Aharon Appelfeld: Return, Repair or Repitition? Sidra DeKoven·Ezrahi In Booking Passage: Exile and Homecoming in the Modern Jewish lmagination 1 I charted the Jewish journey as the pursuit of utopian 1. Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, space in its epic and its anti-epic dimensions. From Yehuda Halevi Booking Passage: Exile through S.Y. Agnon, the journey to reunite self and soul (/ibi ba and Homecoming in the mizrah va-anokhi be-sof ma'arav), the journey to repair the anomaly Modern Jewish Imagination (Berkeley2000). Some of of Galut, was hampered, but also shaped and enriched, by what the ideas developed here are Yehuda Halevi called the 'bounty of Spain' (kol tuv sepharad). explored in the chapter on Appelfeld. Needless to say, the bounty of the homelands that expelled and exterminated the Jews during the Second World War was far more difficult to reclaim or reconstruct than that of twelfth-century Andalusia. Yet even if for the survivors of the Shoah the Jewish journey became that much more urgent and tragic as an exercise in the recovery of a lost continent, the same tension exists in the twentieth - as it did perhaps in the post-traumatic sixteenth century - between kol tuv sepharad and 'Zion', between the personal story and the collective telos, the private narrative and the public topos, the idiosyncratic and the paradigmatic. There is usually not only a tension but a trade-off between the two, a dynamic exchange between the first person singular and plural. After a lifetime of effacing the personal voice in the interstices of a taut and 'public' poetic line, Dan Pagis began in his last years to recover his autobiographical voice in prose. -

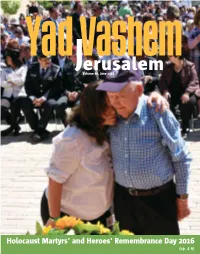

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Modern Hebrew Literature in English Translation

1 Professor Naomi Sokoloff University of Washington Department of Near Eastern Languagse & Civilization Phone: 543-7145 FAX 685-7936 E-mail: [email protected] SYLLABUS MODERN HEBREW LITERATURE IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION NE 325/SISJE 490a 3 credits This survey of modern Hebrew literature and its major developments in the past 100 years includes selections of fiction and poetry by a range of writers from Europe, Israel and the U.S. Among the texts covered are pieces by H.N. Bialik, Dvorah Baron, S.Y. Agnon, Gabriel Preil, Yehuda Amichai, Aharon Appelfeld, Dan Pagis, A.B. Yehoshua, Amos Oz, Etgar Keret, Batya Gur, and more. This course aims to illuminate some of the factors that make this literature distinctive and fascinating. Hebrew is a language that has been in continuous literary use over millennia. Dramatic historical circumstances and ideological forces fostered the revival of the language as a modern tongue and shaped Hebrew literary endeavors up through current time. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: Students are expected to do the required reading, to attend class and to participate in class discussion. There will be several short written assignments, two quizzes and a take-home essay exam. This is a “W” course, which requires significant amounts of writing, editing, and revision. Final grades will be determined as follows: Assignments: #1. A close reading of a poem; 350-750 words (10%) #2. A summary of one of the secondary sources in the recommended reading; 350-750 words (10%) #3. A short essay; 500-750 words (10%) #4. 2 quizzes; one at midterm and one during finals week (20%) #5. -

History, Literature and Culture in Bukovina Romania's "Multi-Kulti" Region

האוניברסיטה העברית בירושלים המרכז לחקר יהדות רומניה The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Center for Research on Romanian Jewry T +972.2.5881672 | F +972.25881673 mail address: [email protected] The Center for Research on Romanian Jewry at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem invites you to a Conference about: History, Literature and Culture in Bukovina Romania's "Multi-Kulti" region The Conference will be held at the Meirsdorf House (room 502) at the Mount Scopus Campus on Tuesday, March 15th, 2016 The Program: 9:00- 9:30 welcome gathering 9:30- 10:00 Greetings Panel Chair: Prof. Uzi Rebhun, Head of the Center for Research on Romanian Jewry Prof. Dror Verman, The Dean of Humanities H.E. Andrea Pasternac, the Romanian Ambassador in Israel Mr. Micha Charish, Chairman of A.M.I.R organization Dr. Saar Pauker, The Pauker Family fund 10:00- 11:15 First Panel: Chair: Prof. Daniel Blatman, The Hebrew University Bukovina and Czernowitz : The Ethnical Uniqueness of the Multi-Cultural city and region Dr. Ronit Fisher, The University of Haifa and the Hebrew University Describing and Imagining Czernowitz – Prof. Zvi Yavetz and His City Dr. Raphael Vago, Tel-Aviv University Back to Czernowitz Dr. Florence Heymann, the Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem 11:15- 11:45 Coffee brake 11:45- 13:30 Second Panel: Chair: Dr.Amos Goldberg, the Hebrew University The Aftermath of Bukovinan Multiculturalism: Paul Celan, Dan Pagis and Aharon Appelfeld, Prof. Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, the Hebrew University Jewish Identity and Soviet Policy in Postwar Chernivtsi: The Case of the All- Ukrainian State Jewish Theater Mrs. -

University of London Thesis

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author C£VJ*r’Nr^'f ^ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Berlin and Jerusalem: Toward German-Hebrew Studies Chapter Author(S): Amir Eshel and Na’Ama Rokem

De Gruyter Chapter Title: Berlin and Jerusalem: Toward German-Hebrew Studies Chapter Author(s): Amir Eshel and Na’ama Rokem Book Title: The German-Jewish Experience Revisited Book Author(s): the Leo Baeck Institute Jerusalem Book Editor(s): Steven E. Aschheim, Vivian Liska Published by: De Gruyter. (2015) Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvbkjwr1.18 JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms This book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Funding is provided by Knowledge Unlatched FID Jewish Studies Collection. De Gruyter is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The German-Jewish Experience Revisited This content downloaded from 73.241.144.250 on Tue, 19 May 2020 17:11:30 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Amir Eshel and Na’ama Rokem Berlin and Jerusalem: Toward German-Hebrew Studies This essay provides an initial mapping of the emerging field of German-Hebrew studies. The field encompasses the study of German-Jewish culture, literature, and thought; the cultural and intellectual history of Zionism; modern Hebrew literature; and contemporary Israeli culture. -

Mikan, Journal for Hebrew and Israeli Literature and Culture Studies

Mikan, Journal for Hebrew and Israeli Literature and Culture Studies Vol. 16, March 2016 מכון והמחלקה לספרות עברית, אוניברסיטת בן־גוריון בנגב Editor: Hanna Soker-Schwager Editorial board: Tamar Alexander, Yitzhak Ben-Mordechai, Yigal Schwartz (Second Editor), Zahava Caspi (Third Editor) Junior editors: Chen Bar-Itzhak, Rina Jean Baroukh, Omer Bar Oz, Yael Ben- Zvi Morad, Tahel Frosh, Maayan Gelbard, Tami Israeli, Yaara Keren, Shachar Levanon, Itay Marienberg-Milikowsky,Rachel Mizrachi-Adam, Yonit Naaman, Yotam Popliker, Efrat Rabinovitz, Yoav Ronel, Tamar Setter. Editorial advisors: Robert Alter, Arnold J. Band, Dan Ben-Amos, Daniel Boyarin, Menachem Brinker, Nissim Calderon, Tova Cohen, Michael Gluzman (First Editor), Nili Scharf Gold, Benjamin Harshav, Galit Hasan-Rokem, Hannan Hever, Ariel Hirschfeld, Avraham Holtz, Avner Holtzman, Matti Huss, Zipporah Kagan, Ruth Kartun-Blum, Chana Kronfeld, Louis Landa, Dan Laor, Avidov Lipsker, Dan Miron, Gilead Morahg, Hannah Nave, Ilana Pardes, Iris Parush, Ilana Rosen, Tova Rosen, Yigal Schwartz, Uzi Shavit, Raymond Sheindlin, Eli Yassif, Gabriel Zoran Editorial coordinator: Irit Ronen, Maayn Gelbard Language editors: Liora Herzig (Hebrew); Daniella Blau (English) Graphic editor: Tamir Lahav-Radlmesser Layout and composition: Srit Rozenberg Cover photo: Disjointed Voices of Birds Behind the Water, 1994, Watercolor on Paper 16x25.4 Jumping FROM One Assuciation to Another, 2008, Black ink and Col on brown cardboard. 28.5x30.5 Hedva Harechavi IBSN: 978-965-566-000-0 All rights reserved © 2016 Heksherim Institute for Jewish and Israeli Literature and Culture, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva, and Kinneret, Zmora-Bitan, Dvir - Publishing House Ltd., Or Yehuda Printed in Israel www.kinbooks.co.il Contents Articles Avidov Lipsker and Lilah Nethanel - The Writing of Space in the Novels Circles and The Closed Gate by David Maletz Tamar Merin - The Purloined Poem: Lea Goldberg Corresponds with U. -

Wiersze Spod Ciemnego Nieba. Geopoezja Czerniowców I Sadogóry1

WIERSZE SPOD CIEMNEGO NIEBA. GEOPOEZJA CZERNIOWCÓW I SADOGÓRY1 JOANNA ROSZAK2 (Poznań) Słowa kluczowe: geopoetyka, żydowscy poeci w Czerniowcach, Paul Celan, Rosa Ausländer Keywords: geopoetics, Jewish poets in Tscherniowitz, Paul Celan, Rosa Ausländer Abstrakt: Joanna Roszak, WIERSZE SPOD CIEMNEGO NIEBA. GEOPOEZJA CZERNIOW- CÓW I SADOGÓRY. „PORÓWNANIA” 8, 2011, Vol. VIII, s. 133–156, ISSN 1733-165X. Artykuł opisuje wielojęzyczny i wielokulturowy fenomen Czerniowców na przełomie dziejów – przed i po II wojnie światowej, widziany przez pryzmat twórczości i biografii żydowskich poetów czer- niowieckich. Metodologiczny kontekst rozważań stanowi geopoetyka – anonsowany od niedawna topograficzny zwrot w badaniach literaturoznawczych w Europie Środkowowschodniej, którego podstawowym założeniem jest nieistniejące dotąd explicite poszukiwanie analogii pomiędzy lektu- rą tekstu i przestrzeni. Autorka przygląda się, jak przestrzeń geograficzna wytwarza zespół reguł i norm organizujących wypowiedź literacką. Autor programowej tezy: „Prawdziwa poezja jest antybiograficzna“, Paul Celan, lubuje się w metaforach geopoetycznych, do przykładów których należy melancholia jako czarne mleko, pojawiająca się także w poezji Rosy Ausländer. Fantazmat Czerniowców staje się w ten sposób figurą powojennej tragedii tych, dla których język niemiecki stanowił naturalny środek artystycznej ekspresji. Odpowiedź na pytanie o miejsce Celana w histo- riach literatur narodowych skłania do konkluzji, że Czerniowce to miasto-probierz dla socjologicz- nych i kulturowych badań nad problematyką tożsamości narodowej. Abstract: Joanna Roszak, POEMS FROM UNDER THE DARK SKY. GEOPOETICS OF TSCHERNOWITZ AND SADOGÓRA. “PORÓWNANIA” 8, 2011, Vol. VIII, s. 133–156, ISSN 1733-165X. The article describes the multilingual and multicultural phenomenon of Tscherno- witz at the turn of the century – before and after the World War II – seen through the prism of the work and biography of the Jewish poets in Tschernowitz. -

The Manifestations of Cultural Memory in the Poetry of Yehuda Amichai

The NEHU Journal, Vol XI, No. 1, January 2013, pp. 55-65, ISSN.0972-9406 The Manifestations of Cultural Memory in the Poetry of Yehuda Amichai EVER E. F. S ANCLEY * Abstract Yehuda Amichai has been widely extolled and universally accommodated for the simplicity and national integrity that is subtly knitted in his poetry. His writings serve as the point of departure and as a model and metaphor for reflection on the significance of literature in the cultural life of the Jewish society besides the construction of individual and national identity. The manifestations of cultural memory in Amichai’s poetry reveal new dimensions of the parameters of the catastrophe following the perpetual atrocities of the Jewish race. The reminiscence of the past, the present and all of time is vividly captured within the ambit of cultural memory and hence a sophisticated study of Amichai’s enormous contribution is obligatory. Keywords : Cultural memory, Jews, Holocaust, Eternal present, Time ehuda Amichai is one of the most celebrated of Hebrew poets in recent years. According to Jonathan Wilson, “He should have won Ythe Nobel Prize in any of the last twenty years” (172). However, politics and the fact that “he came from the wrong side of the Stockade” (ibid ) have denied him that honour. Amichai was a man of humble origin, born to an orthodox Jewish family in Wurzburg, Germany, on 3 May, 1924. He migrated to Palestine in 1935 and consequently to Jerusalem in 1936 where he served as a member of the Palmach , the defence force of the Jewish community in pre-state Israel. -

Encyclopedia of Holocaust Literature

Encyclopedia of Holocaust Literature David Patterson Alan L. Berger Sarita Cargas Editors Oryx Press Encyclopedia of Holocaust Literature Edited by David Patterson, Alan L. Berger, and Sarita Cargas Oryx Holocaust Series Oryx Press Westport, Connecticut • London 4 • The rare Arabian Oryx is believed to have inspired the myth of the unicorn. This desert antelope became virtually extinct in the early 1960s. At that time, several groups of international conservationists arranged to have nine animals sent to the Phoenix Zoo to be the nucleus of a captive breeding herd. Today, the Oryx population is over 1,000, and over 500 have been returned to the Middle East. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of Holocaust literature / edited by David Patterson, Alan L. Berger and Sarita Cargas. p. cm.—(Oryx Holocaust series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–57356–257–2 (alk. paper) 1. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945), in literature—Encyclopedias. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Personal narratives—Encyclopedias. 3. Holocaust, Jewish (1939–1945)—Biography. I. Patterson, David. II. Berger, Alan L., 1939– III. Cargas, Sarita. IV. Series. PN56.H55 E53 2002 809'.93358—dc21 2001036639 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2002 by David Patterson, Alan L. Berger, and Sarita Cargas All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2001036639 ISBN: 1–57356–257–2 First published in 2002 Oryx Press, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. -

Disseminating Jewish Literatures

Disseminating Jewish Literatures Disseminating Jewish Literatures Knowledge, Research, Curricula Edited by Susanne Zepp, Ruth Fine, Natasha Gordinsky, Kader Konuk, Claudia Olk and Galili Shahar ISBN 978-3-11-061899-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-061900-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-061907-2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020908027 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 Susanne Zepp, Ruth Fine, Natasha Gordinsky, Kader Konuk, Claudia Olk and Galili Shahar published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: FinnBrandt / E+ / Getty Images Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Introduction This volume is dedicated to the rich multilingualism and polyphonyofJewish literarywriting.Itoffers an interdisciplinary array of suggestions on issues of re- search and teachingrelated to further promotingthe integration of modern Jew- ish literary studies into the different philological disciplines. It collects the pro- ceedings of the Gentner Symposium fundedbythe Minerva Foundation, which was held at the Freie Universität Berlin from June 27 to 29,2018. During this three-daysymposium at the Max Planck Society’sHarnack House, more than fifty scholars from awide rangeofdisciplines in modern philologydiscussed the integration of Jewish literature into research and teaching. Among the partic- ipants werespecialists in American, Arabic, German, Hebrew,Hungarian, Ro- mance and LatinAmerican,Slavic, Turkish, and Yiddish literature as well as comparative literature. -

Mikan, Journal for Hebrew and Israeli Literature and Culture Studies

Mikan, Journal for Hebrew and Israeli Literature and Culture Studies Vol. 12, December 2012 מכון והמחלקה לספרות עברית, אוניברסיטת בן־גוריון בנגב Editor in chief: Zahawa Caspi Guest editor: Batya Shimony Editorial board: Tamar Alexander, Yitzhak Ben-Mordechai, Yigal Schwartz (Second Editor) Junior editors: Yael Balaban, Noga Cohen, Lior Granot, Sharon Greenberg-Lior, Nirit Kurman, Adi Moneta, Miri Peled, Chen Shtrass, Dror Yosef Editorial advisors: Robert Alter, Arnold J. Band, Dan Ben-Amos, Daniel Boyarin, Menachem Brinker, Nissim Calderon, Tova Cohen, Michael Gluzman (First Editor), Nili Scharf Gold, Benjamin Harshav, Galit Hasan-Rokem, Hannan Hever, Ariel Hirschfeld, Avraham Holtz, Avner Holtzman, Matti Huss, Zipporah Kagan, Ruth Kartun-Blum, Chana Kronfeld, Louis Landa, Dan Laor, Avidov Lipsker, Dan Miron, Gilead Morahg, Hannah Nave, Ilana Pardes, Iris Parush, Ilana Rosen, Tova Rosen, Yigal Schwartz, Gershon Shaked (1929-2006), Uzi Shavit, Raymond Sheindlin, Eli Yassif, Gabriel Zoran Editorial coordinator: Miri Peled, Chen Shtrass Language editors: Liora Herzig (Hebrew); Michael Boyden (English) Graphic editor: Tamir Lahav-Radlmesser Layout and composition: Sarit Savlan IBSN: 978-965-552-477-2 All rights reserved © 2012 Heksherim Institute for Jewish and Israeli Literature and Culture, Ben Gurion University, Beer Sheva, and Kinneret, Zmora-Bitan, Dvir - Publishing House Ltd., Or Yehuda Printed in Israel www.kinbooks.co.il Contents Articles Nili Rachel Scharf Gold The Betrayal of the Mother Tongue in the Works of Hoffman, Zach, Amichai