The Jewish Journey in the Late Fiction of Aharon Appelfeld: Return, Repair Or Repitition?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"And a Small Boy Leading Them": the Child and the Biblical Landscape in Agnon, Oz, and Appelfeld Author(S): Nehama Aschkenasy Source: AJS Review, Vol

"And a Small Boy Leading Them": The Child and the Biblical Landscape in Agnon, Oz, and Appelfeld Author(s): Nehama Aschkenasy Source: AJS Review, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Apr., 2004), pp. 137-156 Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Association for Jewish Studies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4131513 Accessed: 11-05-2015 23:17 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4131513?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/ info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Cambridge University Press and Association for Jewish Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to AJS Review. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Mon, 11 May 2015 23:17:40 UTC All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions AJS Review 28:1 (2004), 137-156 "AND A SMALL BOY LEADING THEM": The Child and the Biblical Landscape in Agnon, Oz, andAppelfeld* by NehamaAschkenasy Each of the three childhood stories, S. Y. Agnon's -

Choice of Language and the Quest for Israeli Identity in the Works of Tuvia Ruebner and Aharon Appelfeld

POLISH POLITICAL SCIENCE YEARBOOK, vol. 47(2) (2018), pp. 414–423 DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15804/ppsy2018219 PL ISSN 0208-7375 www.czasopisma.marszalek.com.pl/10-15804/ppsy Michal Ben-Horin Bar-Ilan University in Ramat-Gan (Israel) Choice of Language and the Quest for Israeli Identity in the Works of Tuvia Ruebner and Aharon Appelfeld Abstract: Immigration highlights the question of language and raises the dilemma of the relationship between the mother tongue and the language of the new land. For writers this question is even more crucial: should they write in the language of the place and its readers? Immigration to Israel is not exceptional, of course. What choices are open to those writers, and how are they to convey the complexities inherent in the formation of an Israeli identity? This paper focuses on two writers who demonstrate the role played by the “chosen language” in the cultural construction and deconstruction of Israeli identity. Tuvia Ruebner emigrated from Bratislava, Aharon Appelfeld from Bukovina. Ruebner shifted from German to Hebrew and back to German; Appelfeld wrote only in Hebrew. In both cases, their arrival in Israel en- abled them to survive. However, the loss of their families in Europe continued to haunt them. Inspired by Walter Benjamin’s concept of ‘translation’ and responding to Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari’s concept of ‘minor literature’, the paper shows how their work conveys a mul- tilayered interrelation between national and foreign languages, and between images of exile and homeland, past, present and future – all of which shed light on contemporary issues of Israeli identity. -

How Family Holocaust Stories Became Multimedia Art Exhibit

Forward.com Arts & Culture How Family Holocaust Stories Became Multimedia Art Exhibit Aliza Augustine and Janet Kirchheimer Portray Wartime Experiences By Rukhl Schaechter Published February 21, 2015. A version of this article appeared in Yiddish here. Children of Holocaust survivors can be split into two groups: those whose parents or grandparents said nothing about those harrowing years, and those whose relatives gave them detailed accounts of their experiences. I belong to the first category. Although my father’s family had, like all the Jews of Chernivtsi (known in Yiddish as Chernovits), been crammed into a ghetto, he never told any of us children about it. Whenever I asked about his experience, his reply was, “I don’t remember.” The subject was probably too painful for him to discuss. But Aliza Augustine and Janet R. Kirchheimer are of the second category. Throughout their childhood, their relatives gave them detailed accounts of their experiences during the war. Today, both women feel a personal responsibility to share their stories with the next generation — not simply by telling people what happened, but by portraying the experience through the arts. Augustine does it through photography, and Kirchheimer through poetry and film. The two women met two years ago at a conference for children of Holocaust survivors and began discussing how they could use their art to further Holocaust remembrance. The result of their collaboration is now on view until May 18 at the Human Rights Institute Gallery at Kean University, in Union County, New Jersey, in an exhibit titled “How To Spot One of Us.” One part of the exhibit features Augustine’s narrative portraits of grown children of survivors, each displaying an old family photograph and set against a contemporary landscape photographed by Augustine during a trip to Europe in 2013. -

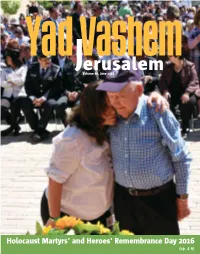

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Disseminating Jewish Literatures

Disseminating Jewish Literatures Disseminating Jewish Literatures Knowledge, Research, Curricula Edited by Susanne Zepp, Ruth Fine, Natasha Gordinsky, Kader Konuk, Claudia Olk and Galili Shahar ISBN 978-3-11-061899-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-061900-3 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-061907-2 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2020908027 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2020 Susanne Zepp, Ruth Fine, Natasha Gordinsky, Kader Konuk, Claudia Olk and Galili Shahar published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Cover image: FinnBrandt / E+ / Getty Images Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Introduction This volume is dedicated to the rich multilingualism and polyphonyofJewish literarywriting.Itoffers an interdisciplinary array of suggestions on issues of re- search and teachingrelated to further promotingthe integration of modern Jew- ish literary studies into the different philological disciplines. It collects the pro- ceedings of the Gentner Symposium fundedbythe Minerva Foundation, which was held at the Freie Universität Berlin from June 27 to 29,2018. During this three-daysymposium at the Max Planck Society’sHarnack House, more than fifty scholars from awide rangeofdisciplines in modern philologydiscussed the integration of Jewish literature into research and teaching. Among the partic- ipants werespecialists in American, Arabic, German, Hebrew,Hungarian, Ro- mance and LatinAmerican,Slavic, Turkish, and Yiddish literature as well as comparative literature. -

Modern Hebrew Literature in English Translation

1 Professor Naomi Sokoloff University of Washington Department of Near Eastern Languagse & Civilization Phone: 543-7145 FAX 685-7936 E-mail: [email protected] SYLLABUS MODERN HEBREW LITERATURE IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION NE 325/SISJE 490a 3 credits This survey of modern Hebrew literature and its major developments in the past 100 years includes selections of fiction and poetry by a range of writers from Europe, Israel and the U.S. Among the texts covered are pieces by H.N. Bialik, Dvorah Baron, S.Y. Agnon, Gabriel Preil, Yehuda Amichai, Aharon Appelfeld, Dan Pagis, A.B. Yehoshua, Amos Oz, Etgar Keret, Batya Gur, and more. This course aims to illuminate some of the factors that make this literature distinctive and fascinating. Hebrew is a language that has been in continuous literary use over millennia. Dramatic historical circumstances and ideological forces fostered the revival of the language as a modern tongue and shaped Hebrew literary endeavors up through current time. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: Students are expected to do the required reading, to attend class and to participate in class discussion. There will be several short written assignments, two quizzes and a take-home essay exam. This is a “W” course, which requires significant amounts of writing, editing, and revision. Final grades will be determined as follows: Assignments: #1. A close reading of a poem; 350-750 words (10%) #2. A summary of one of the secondary sources in the recommended reading; 350-750 words (10%) #3. A short essay; 500-750 words (10%) #4. 2 quizzes; one at midterm and one during finals week (20%) #5. -

History, Literature and Culture in Bukovina Romania's "Multi-Kulti" Region

האוניברסיטה העברית בירושלים המרכז לחקר יהדות רומניה The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Center for Research on Romanian Jewry T +972.2.5881672 | F +972.25881673 mail address: [email protected] The Center for Research on Romanian Jewry at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem invites you to a Conference about: History, Literature and Culture in Bukovina Romania's "Multi-Kulti" region The Conference will be held at the Meirsdorf House (room 502) at the Mount Scopus Campus on Tuesday, March 15th, 2016 The Program: 9:00- 9:30 welcome gathering 9:30- 10:00 Greetings Panel Chair: Prof. Uzi Rebhun, Head of the Center for Research on Romanian Jewry Prof. Dror Verman, The Dean of Humanities H.E. Andrea Pasternac, the Romanian Ambassador in Israel Mr. Micha Charish, Chairman of A.M.I.R organization Dr. Saar Pauker, The Pauker Family fund 10:00- 11:15 First Panel: Chair: Prof. Daniel Blatman, The Hebrew University Bukovina and Czernowitz : The Ethnical Uniqueness of the Multi-Cultural city and region Dr. Ronit Fisher, The University of Haifa and the Hebrew University Describing and Imagining Czernowitz – Prof. Zvi Yavetz and His City Dr. Raphael Vago, Tel-Aviv University Back to Czernowitz Dr. Florence Heymann, the Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem 11:15- 11:45 Coffee brake 11:45- 13:30 Second Panel: Chair: Dr.Amos Goldberg, the Hebrew University The Aftermath of Bukovinan Multiculturalism: Paul Celan, Dan Pagis and Aharon Appelfeld, Prof. Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, the Hebrew University Jewish Identity and Soviet Policy in Postwar Chernivtsi: The Case of the All- Ukrainian State Jewish Theater Mrs. -

Holocaust Child Survivors' Memoirs As Reflected in Appelfeld's the Story of a Life

CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture ISSN 1481-4374 Purdue University Press ©Purdue University Volume 17 (2015) Issue 3 Article 12 Holocaust Child Survivors' Memoirs as Reflected in Appelfeld's The Story of a Life Dana Mihăilescu University of Bucharest Follow this and additional works at: https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/clcweb Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Education Commons, European Languages and Societies Commons, Other Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Dedicated to the dissemination of scholarly and professional information, Purdue University Press selects, develops, and distributes quality resources in several key subject areas for which its parent university is famous, including business, technology, health, veterinary medicine, and other selected disciplines in the humanities and sciences. CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture, the peer-reviewed, full-text, and open-access learned journal in the humanities and social sciences, publishes new scholarship following tenets of the discipline of comparative literature and the field of cultural studies designated as "comparative cultural studies." Publications in the journal are indexed in the Annual Bibliography of English Language and Literature (Chadwyck-Healey), the Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Thomson Reuters ISI), the Humanities Index (Wilson), Humanities International Complete (EBSCO), the International Bibliography of the Modern Language Association of America, and Scopus (Elsevier). The journal is affiliated with the Purdue University Press monograph series of Books in Comparative Cultural Studies. Contact: <[email protected]> Recommended Citation Mihăilescu, Dana. "Holocaust Child Survivors' Memoirs as Reflected in Appelfeld's The Story of a Life." CLCWeb: Comparative Literature and Culture 17.3 (2015): <https://doi.org/10.7771/1481-4374.2711> This text has been double-blind peer reviewed by 2+1 experts in the field. -

Badenheim 1939 and Amos Oz's Touch the Water, Touch the Wind

STUDENT SECTION Israeli Holocaust Fiction: A Review of Aharon Appelfeld's Badenheim 1939 and Amos Oz's Touch the Water, Touch the Wind NAOMI HETHERINGTON Elie Wiesel, himself a prolific Holocaust writer, declared in an open lecture at Northwestern University, 'The literature of the holocaust . There is no such thing.' 1 The atrocity of the Shoah is perhaps unprecedented in human history in its huge scale, and the technological exactness with which it was perpetrated. Attempting to represent it in literature or art incurs the danger of in some sense justifying it by using it to aesthetic ends. Depicting horror can sometimes domesticate it, rendering it more familiar or tolerable - a false assurance which the reader or viewer may welcome or even be tacitly expecting. Furthermore, the genre of fiction goes beyond memoir in its interpretive nature so that it contains the temptation to glean from the Shoah a redemptive meaning where perhaps there is none. In addition, there remains the question, do those who have not experienced the Holocaust personally have the right to write about it at all? Naomi Hetherington is currently reading an MAin Nineteenth Cenrury English Literature at Manchester University. She graduated in summer 1996 with a first class degree in Theology and Religious Studies from Newnham College, Cambridge. This article is adapted from a third year paper on 'Jewish and Christian Responses to the Holocaust'. The Journal of Holocaust Education, Voi.S, No.1, Summer 1996, pp.49-60 PUBLISHED BY FRANK CASS, LONDON 50 THE JOURNAL OF HOLOCAUST EDUCATION Different writers have attempted different ways of surmounting these barriers. -

University of London Thesis

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree Year Name of Author C£VJ*r’Nr^'f ^ COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOAN Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the University Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: The Theses Section, University of London Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the University of London Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The University Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Adam & Thomas Written by Aharon Appelfeld Illustrated by Philipe

Book Review: Adam and Thomas, Aharon Appelfeld Item Type Book Review; text Authors Baumgarten, Shelley Citation Baumgarten, Shelley. (2021). Book Review: Adam and Thomas, Aharon Appelfeld. WOW Review. Publisher Worlds of Words: Center for Global Literacies and Literatures (University of Arizona) Journal WOW Review Rights © The Author(s). Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0). Download date 23/09/2021 11:01:50 Item License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ Version Final published version Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/661177 WOW Review: Volume XIII, Issue 3 Summer 2021 Adam & Thomas Written by Aharon Appelfeld Illustrated by Philipe Dumas Translated by Jeffery Green Seven Stories Press, 2017, 149 pp ISBN: 978-1-60980-744-3 Part autobiography, part fable, Batchelder Award Honor Book Adam & Thomas, by Holocaust survivor Aharon Appelfeld, is a tale of two nine-year-old Jewish boys and their survival in the forests of Ukraine toward the end of the Nazi occupation of Eastern Europe during World War II. Each boy is brought to a large forest separately by their mothers who leave them as Jewish ghettos are emptied and Jews are transported to concentration and death camps as part of Hitler’s Final Solution. Adam, described by Appelfeld as a child of nature, and Thomas, a pensive and serious child of the city, come to rely on each other and survive together. Throughout, Adam teaches Thomas how to survive in the woods, serving as an example of self-sufficiency and strength while Thomas, a sensitive and gifted writer, records their daily activities. -

The Heartache of Two Homelands…’: Ideological and Emotional Perspectives on Hebrew Translingual Writing

L2 Journal, Volume 7 (2015), pp. 30-48 http://repositories.cdlib.org/uccllt/l2/vol7/iss1/art4/ ‘The Heartache of Two Homelands…’: Ideological and Emotional Perspectives on Hebrew Translingual Writing MICHAL TANNENBAUM Tel Aviv University E-mail: [email protected] The work of immigrant writers, whose professional identity is built around language, can deepen understandings of sociolinguistic and psychological issues, including aspects of the immigration experience; the position of language in the ideological and emotional value systems, and the significance of language for individual development. This paper deals with a number of translingual writers who immigrated to Israel prior to its establishment as an independent state and who chose Hebrew as their language. The paper focuses on three figures—Alexander Penn, Leah Goldberg, and Aharon Appelfeld—who came from different countries and different language backgrounds but have in common that Hebrew was not their first language. Two issues are discussed in depth in this article. One is the unique position of Hebrew, a language that retains high symbolic significance given its association with holy texts and the ideological role its revival played in the Zionist enterprise. Its association with identity issues or childhood memories may thus be somewhat different from that of other second languages. The other issue is the psychological motivations that affected these writers’ language shift. Despite the broad consensus on this shift as having been inspired by ideological/Zionist motives, my claim is that their motives may have been broader. Ideologies may at times serve as camouflage—used either by wider society’s collective interest in promoting its ethos, or by the individuals themselves, who prefer to be viewed as part of the collective and lean on its ideology to serve their own psychological needs.