Sacrificial Space: the Hebrew Imagination “Comes Home” 115

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Jewish Journey in the Late Fiction of Aharon Appelfeld: Return, Repair Or Repitition?

The Jewish Journey in the Late fiction of Aharon Appelfeld: Return, Repair or Repitition? Sidra DeKoven·Ezrahi In Booking Passage: Exile and Homecoming in the Modern Jewish lmagination 1 I charted the Jewish journey as the pursuit of utopian 1. Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, space in its epic and its anti-epic dimensions. From Yehuda Halevi Booking Passage: Exile through S.Y. Agnon, the journey to reunite self and soul (/ibi ba and Homecoming in the mizrah va-anokhi be-sof ma'arav), the journey to repair the anomaly Modern Jewish Imagination (Berkeley2000). Some of of Galut, was hampered, but also shaped and enriched, by what the ideas developed here are Yehuda Halevi called the 'bounty of Spain' (kol tuv sepharad). explored in the chapter on Appelfeld. Needless to say, the bounty of the homelands that expelled and exterminated the Jews during the Second World War was far more difficult to reclaim or reconstruct than that of twelfth-century Andalusia. Yet even if for the survivors of the Shoah the Jewish journey became that much more urgent and tragic as an exercise in the recovery of a lost continent, the same tension exists in the twentieth - as it did perhaps in the post-traumatic sixteenth century - between kol tuv sepharad and 'Zion', between the personal story and the collective telos, the private narrative and the public topos, the idiosyncratic and the paradigmatic. There is usually not only a tension but a trade-off between the two, a dynamic exchange between the first person singular and plural. After a lifetime of effacing the personal voice in the interstices of a taut and 'public' poetic line, Dan Pagis began in his last years to recover his autobiographical voice in prose. -

Re-Read the Passage of Scripture Matthew 1:1-17 the Book of The

Re-read the passage of Scripture Matthew 1:1-17 The book of the genealogy of Jesus Christ, the son of David, the son of Abraham. 2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, and Isaac the father of Jacob, and Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, 3 and Judah the father of Perez and Zerah by Tamar, and Perez the father of Hezron, and Hezron the father of Ram, 4 and Ram the father of Amminadab, and Amminadab the father of Nahshon, and Nahshon the father of Salmon, 5 and Salmon the father of Boaz by Rahab, and Boaz the father of Obed by Ruth, and Obed the father of Jesse, 6 and Jesse the father of David the king. And David was the father of Solomon by the wife of Uriah, 7 and Solomon the father of Rehoboam, and Rehoboam the father of Abijah, and Abijah the father of Asaph, 8 and Asaph the father of Jehoshaphat, and Jehoshaphat the father of Joram, and Joram the father of Uzziah, 9 and Uzziah the father of Jotham, and Jotham the father of Ahaz, and Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, 10 and Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, and Manasseh the father of Amos, and Amos the father of Josiah, 11 and Josiah the father of Jechoniah and his brothers, at the time of the deportation to Babylon. 12 And after the deportation to Babylon: Jechoniah was the father of Shealtiel, and Shealtiel the father of Zerubbabel, 13 and Zerubbabel the father of Abiud, and Abiud the father of Eliakim, and Eliakim the father of Azor, 14 and Azor the father of Zadok, and Zadok the father of Achim, and Achim the father of Eliud, 15 and Eliud the father of Eleazar, and Eleazar the father of Matthan, and Matthan the father of Jacob, 16 and Jacob the father of Joseph the husband of Mary, of whom Jesus was born, who is called Christ. -

2011 Newsletter

Connecting Cultures Around The World CHAIRMAN IN MEMORIAM Isaac Stern Israeli Artists Around the World CHAIRMAN EMERITA Vera Stern - The Cultural Connection - OFFICERS William A. Schwartz, PRESIDENT Barbara Samuelson, VICE PRESIDENT The impact of Israeli culture keeps expanding. Every Linda Schonfeld, SECRETARY Joseph E. Hollander, TREASURER year, our scholarship recipients are winning seats in Jonathan E. Goldberg, ASSISTANT SECRETARY Stephanie Feldman, ASSISTANT TREASURER the most prestigious orchestras, earning top prizes at international film festivals, showing in respected BOARD OF DIRECTORS Sanford L. Batkin galleries, and performing on Broadway. All over the Diane Belfer Ann Bialkin world, AICF artists are sharing their passion with the Renée Cherniak* world. For this reason, we are creating an international Lonny Darwin Debby B. Edelsohn* cultural calendar and database to connect artists, Stephanie Feldman Avri Fuchs donors, and audiences. Jonathan E. Goldberg Charlotte S. Hattenbach* Ora Holin Joseph E. Hollander Stephanie Katzovicz Jane Stern Lebell Bradley Lubin Wendy Marks Marguerite Perkins-Mautner* Helen Sax Potaznik The Artist Network Sandra Rothman Tamar Rudich Barbara Samuelson Linda Schonfeld Renée Schreiber William A. Schwartz Romie Shapiro Carol Starley* *Chapter President EXECUTIVE DIRECTORS David Homan, USA Orit Naor, Israel ARTS ADVISORY COMMITTEE Jacques d’Amboise Milton Babbitt Menashe Kadishman Joseph Kalichstein Tel Aviv Zubin Mehta Itzhak Perlman Dina Recanati For many of our artists, their first steps are in Tel Aviv. John Rubinstein There’s a reason for this—Richard Florida’s The Rise of the Robert Sherman Creative Class ranks Tel Aviv among the top twenty cities in Joan Miklin Silver Neil Simon the world for global creativity. -

Studying the Book of Matthew in Small Group Discussions

STUDYING THE BOOK OF MATTHEW IN SMALL GROUP DISCUSSIONS Lesson 1 - The Genealogy of Jesus - Matthew 1:1-17 Read the following verses in the New International Version or a translation of your choice. Then discuss the questions that follow. Questions should be studied by each individual before your discussion group meets. Materials may be copied and used for Bible study purposes. Not to be sold. MT 1:1 A record of the genealogy of Jesus Christ the son of David, the son of Abraham: MT 1:2 Abraham was the father of Isaac, Isaac the father of Jacob, Jacob the father of Judah and his brothers, MT 1:3 Judah the father of Perez and Zerah, whose mother was Tamar, Perez the father of Hezron, Hezron the father of Ram, MT 1:4 Ram the father of Amminadab, Amminadab the father of Nahshon, Nahshon the father of Salmon, MT 1:5 Salmon the father of Boaz, whose mother was Rahab, Boaz the father of Obed, whose mother was Ruth, Obed the father of Jesse, MT 1:6 and Jesse the father of King David. David was the father of Solomon, whose mother had been Uriah's wife, MT 1:7 Solomon the father of Rehoboam, Rehoboam the father of Abijah, Abijah the father of Asa, MT 1:8 Asa the father of Jehoshaphat, Jehoshaphat the father of Jehoram, Jehoram the father of Uzziah, MT 1:9 Uzziah the father of Jotham, Jotham the father of Ahaz, Ahaz the father of Hezekiah, MT 1:10 Hezekiah the father of Manasseh, Manasseh the father of Amon, Amon the father of Josiah, 1 MT 1:11 and Josiah the father of Jeconiah* and his brothers at the time of the exile to Babylon. -

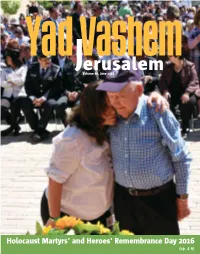

Jerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016

Yad VaJerusalemhem Volume 80, June 2016 Holocaust Martyrs' and Heroes' Remembrance Day 2016 (pp. 4-9) Yad VaJerusalemhem Contents Volume 80, Sivan 5776, June 2016 Inauguration of the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on the Holocaust in the Soviet Union ■ 2-3 Published by: Highlights of Holocaust Remembrance Day 2016 ■ 4-5 Students Mark Holocaust Remembrance Day Through Song, Film and Creativity ■ 6-7 Leah Goldstein ■ Remembrance Day Programs for Israel’s Chairman of the Council: Rabbi Israel Meir Lau Security Forces ■ 7 Vice Chairmen of the Council: ■ On 9 May 2016, Yad Vashem inaugurated Dr. Yitzhak Arad Torchlighters 2016 ■ 8-9 Dr. Moshe Kantor the Moshe Mirilashvili Center for Research on ■ 9 Prof. Elie Wiesel “Whoever Saves One Life…” the Holocaust in the Soviet Union, under the Chairman of the Directorate: Avner Shalev Education ■ 10-13 auspices of its world-renowned International Director General: Dorit Novak Asper International Holocaust Institute for Holocaust Research. Head of the International Institute for Holocaust Studies Program Forges Ahead ■ 10-11 The Center was endowed by Michael and Research and Incumbent, John Najmann Chair Laura Mirilashvili in memory of Michael’s News from the Virtual School ■ 10 for Holocaust Studies: Prof. Dan Michman father Moshe z"l. Alongside Michael and Laura Chief Historian: Prof. Dina Porat Furthering Holocaust Education in Germany ■ 11 Miriliashvili and their family, honored guests Academic Advisor: Graduate Spotlight ■ 12 at the dedication ceremony included Yuli (Yoel) Prof. Yehuda Bauer Imogen Dalziel, UK Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset; Zeev Elkin, Members of the Yad Vashem Directorate: Minister of Immigration and Absorption and Yossi Ahimeir, Daniel Atar, Michal Cohen, “Beyond the Seen” ■ 12 Matityahu Drobles, Abraham Duvdevani, New Multilingual Poster Kit Minister of Jerusalem Affairs and Heritage; Avner Prof. -

Modern Hebrew Literature in English Translation

1 Professor Naomi Sokoloff University of Washington Department of Near Eastern Languagse & Civilization Phone: 543-7145 FAX 685-7936 E-mail: [email protected] SYLLABUS MODERN HEBREW LITERATURE IN ENGLISH TRANSLATION NE 325/SISJE 490a 3 credits This survey of modern Hebrew literature and its major developments in the past 100 years includes selections of fiction and poetry by a range of writers from Europe, Israel and the U.S. Among the texts covered are pieces by H.N. Bialik, Dvorah Baron, S.Y. Agnon, Gabriel Preil, Yehuda Amichai, Aharon Appelfeld, Dan Pagis, A.B. Yehoshua, Amos Oz, Etgar Keret, Batya Gur, and more. This course aims to illuminate some of the factors that make this literature distinctive and fascinating. Hebrew is a language that has been in continuous literary use over millennia. Dramatic historical circumstances and ideological forces fostered the revival of the language as a modern tongue and shaped Hebrew literary endeavors up through current time. COURSE REQUIREMENTS: Students are expected to do the required reading, to attend class and to participate in class discussion. There will be several short written assignments, two quizzes and a take-home essay exam. This is a “W” course, which requires significant amounts of writing, editing, and revision. Final grades will be determined as follows: Assignments: #1. A close reading of a poem; 350-750 words (10%) #2. A summary of one of the secondary sources in the recommended reading; 350-750 words (10%) #3. A short essay; 500-750 words (10%) #4. 2 quizzes; one at midterm and one during finals week (20%) #5. -

Israeli & International Art Jerusalem 16 April 2009

ISRAELI & INTERNATIONAL ART JERUSALEM 16 APRIL 2009 SPECIAL PESACH AUCTION ISRAELI AND INTERNATIONAL ART KING DAVID HOTEL JERUSALEM THURSDAY, 16 APRIL 2009 9:00 P.M. 1 בס”ד Auction Preview MATSART GALLERY, 21 King David St., Jerusalem April 2 -16 : Sun.-Thu. (including Hol-Hamoed) 11 am - 10 pm Fri. 11 am - 3 pm Sat. and Holidays 9.30 pm - 12 am Wed. April 8 (Erev Pesach) by appointment only Thu. April 16, 11 am - 2 pm Private viewing is available by appointment Online auction on : www.artfact.com Online Catalogue : www.artonline.co.il Auction 111, 16 April 2009 9:00 pm King David Hotel, Jerusalem. Special preview of selected lots Auction 112 (June 2009) on view in the gallery.(See highlights on p. 106 -113) ימי תצוגה גלריה מצארט, דוד המלך 21 ירושלים 16-2 אפריל. ראשון - חמישי ׁׂׂ)כולל חול המועד( 11:00 - 22:00 שישי 11:00 - 15:00, שבת ומוצאי חג 21:30 - 24:00 רביעי, 6 אפריל )ערב פסח( לפי תיאום מראש. חמישי, 16 אפריל 11:00 - 14:00 המכירה גם באתר : www.artfact.co.il הקטלוג און-ליין בכתובת: www.artonline.co.il מכירה 111 16 באפריל 2009, 21:00, מלון המלך דוד, ירושלים מבחר פריטים ממכירה 112 )יוני 2009( יוצגו בגלריה בימי התצוגה המקדימה )ראה יצירות נבחרות בעמ’ 113-106( 3 מנהל ובעלים Director and Owner לוסיאן קריאף Lucien Krief מנכ”ל Executive Director אורי רוזנבך Uri Rosenbach [email protected] [email protected] מומחים Specialists אורן מגדל Oren Migdal מומחה לאמנות ישראלית Expert Israeli Art [email protected] [email protected] לוסיאן קריאף Lucien Krief מומחה לאסכולת פריז Expert Ecole de Paris [email protected] [email protected] שירות לקוחות Client Relations אורי רוזנבך Uri Rosenbach ברברה אפלבאום Barbara Apelbaum [email protected] [email protected] כספים Client Accounts סטלה קוסטה Stella Costa [email protected] [email protected] לוגיסטיקה ומשלוחים Logistics and Shipping רייזי גודווין Reizy Goodwin [email protected] [email protected] MATSART AUCTIONEERS AND APPRAISERS 21 King David St. -

Israeli) Star of Hope Agamograph 29 X 31 Cm (11 X 12 In.) Signed Lower Right, Numbered '8/25' Lower Left

1* Yaacov Agam b.1928 (Israeli) Star of Hope agamograph 29 x 31 cm (11 x 12 in.) signed lower right, numbered '8/25' lower left $1,500-1,800 2* Yaacov Agam b.1928 (Israeli) Untitled color silkscreen mounted on panel 57 x 62 cm (22 x 24 in.) signed lower right, numbered 'L/CXLIV' lower left $400-500 3 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Sheep head acrylic on canvas 30 x 30 cm (12 x 12 in.) signed lower left and again on the reverse $450-550 4 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Motherland charcoal on paper 27 x 35 cm (11 x 14 in.) signed lower right $150-220 5 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Valley of sadness pencil on paper 27 x 35 cm (11 x 14 in.) signed lower right $100-150 6* Ruth Schloss 1922-2013 (Israeli) 1 Girl in red dress, 1965 oil on canvas 74 x 50 cm (29 x 20 in.) signed lower right Provenance: Private collection, USA. $3,500-4,000 7 Sami Briss b.1930 (Israeli, French) Doves oil on wood 8 x 10 cm (3 x 4 in.) signed lower center $500-650 8 Nahum Gilboa b.1917 (Israeli) Rural landscape with wooden bridge mixed media on canvasboard 23 x 30 cm (9 x 12 in.) signed lower right, signed and titled on the reverse $1,800-2,200 9 Audrey Bergner b.1927 (Israeli) Flutist oil on canvas 40 x 30 cm (16 x 12 in.) signed lower right, signed and titled on the reverse $4,800-5,500 10 Yohanan Simon 1905-1976 (Israeli) Vegetarian Evolution, 1971 oil on canvas 46 x 54 cm (18 x 21 in.) signed in English lower left, signed in Hebrew and dated lower right, signed, dated and titled on the stretcher $8,000-10,000 11* Yohanan Simon 1905-1976 (Israeli) Wedding, 1969 2 oil on canvas 15 x 23 cm (6 x 9 in.) signed in English lower left and in Hebrew lower right $2,200-2,500 12 Menashe Kadishman 1932-2015 (Israeli) Fallow deer iron cut-out 34 x 30 x 2 cm (13 x 12 x 1 in.) initialled $1,400-1,600 13 Naftali Bezem b. -

History, Literature and Culture in Bukovina Romania's "Multi-Kulti" Region

האוניברסיטה העברית בירושלים המרכז לחקר יהדות רומניה The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Center for Research on Romanian Jewry T +972.2.5881672 | F +972.25881673 mail address: [email protected] The Center for Research on Romanian Jewry at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem invites you to a Conference about: History, Literature and Culture in Bukovina Romania's "Multi-Kulti" region The Conference will be held at the Meirsdorf House (room 502) at the Mount Scopus Campus on Tuesday, March 15th, 2016 The Program: 9:00- 9:30 welcome gathering 9:30- 10:00 Greetings Panel Chair: Prof. Uzi Rebhun, Head of the Center for Research on Romanian Jewry Prof. Dror Verman, The Dean of Humanities H.E. Andrea Pasternac, the Romanian Ambassador in Israel Mr. Micha Charish, Chairman of A.M.I.R organization Dr. Saar Pauker, The Pauker Family fund 10:00- 11:15 First Panel: Chair: Prof. Daniel Blatman, The Hebrew University Bukovina and Czernowitz : The Ethnical Uniqueness of the Multi-Cultural city and region Dr. Ronit Fisher, The University of Haifa and the Hebrew University Describing and Imagining Czernowitz – Prof. Zvi Yavetz and His City Dr. Raphael Vago, Tel-Aviv University Back to Czernowitz Dr. Florence Heymann, the Centre de recherche français à Jérusalem 11:15- 11:45 Coffee brake 11:45- 13:30 Second Panel: Chair: Dr.Amos Goldberg, the Hebrew University The Aftermath of Bukovinan Multiculturalism: Paul Celan, Dan Pagis and Aharon Appelfeld, Prof. Sidra DeKoven Ezrahi, the Hebrew University Jewish Identity and Soviet Policy in Postwar Chernivtsi: The Case of the All- Ukrainian State Jewish Theater Mrs. -

Nohra Haime Gallery

NOHRA HAIME GALLERY MENASHE KADISHMAN (1932-2015) 1932 Born in Tel Aviv, Israel 1950-53 Works as a shepherd in Kibbutz Ma'ayan Baruch and Kibbutz Yizreel 1959 Moves to London 1972 Moves back to Tel Aviv EDUCATION 1947-50 Studies with sculptor Moshe Sternschuss, Avni Institute, Tel Aviv 1954 Studies with sculptor Rudi Lehman, Jerusalem 1959-61 St. Martin's School of Art, London 1961-62 Slade School of Art, University of London PRIZES AND AWARDS 1960 America-Israel Cultural Foundation Scholarship 1961 Sainsbury Scholarship, London 1967 First Prize for Sculpture, 5th Paris Biennale 1978 Sandberg Prize, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem 1981 The Eugen Kolb Prize, The Tel Aviv Museum Prize of the Jury, Norwegian International Print Biennale, Fredrickstad 1984 The Pundik Prize, The Tel Aviv Museum 1989 King Solomon Award, America-Israel Foundation, New York ONE-PERSON EXHIBITIONS 1965 Grosvenor Gallery, London, England Harlow Arts Festival, Harlow, England 1967 Dunkelman Gallery, Toronto, Canada 1968 Goldberg Gallery, Edinburgh, Scotland 1970 The Jewish Museum, New York 1971 J.L. Hudson Gallery, Detroit, MI 1972 Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, West Germany 1975 Israel Museum, Jerusalem, Israel Julie M. Gallery, Tel Aviv 1976 Rina Gallery, New York 1977 Unikorn Gallery, Copenhagen, Denmark 1978 Venice Biennale, Venice 1979 Israel Museum, Jerusalem: The Kadishman Connection Sari Levi Gallery, Tel Aviv 1981 Argaman Gallery, Tel Aviv University of Haifa Art Gallery, Haifa, Israel Sara Gilat Gallery, Jerusalem Goldman Gallery, Haifa Tel Aviv Museum, Tel Aviv 1982 Julie M. Gallery, Tel Aviv 500 WEST 21ST STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10011 212-888-3550 f: 212-888-7869 [email protected] nohrahaimegallery.com Sara Gilat Gallery, Jerusalem Art 13, Goldman Gallery, Basel, Switzerland 1983 Muhlenberg College, Allentown, PA CIAE, Goldman Gallery, Chicago, IL 1984 Julie M. -

The Internal Consistency and Historical Reliability of the Biblical Genealogies

Vetus Testamentum XL, 2 (1990) THE INTERNAL CONSISTENCY AND HISTORICAL RELIABILITY OF THE BIBLICAL GENEALOGIES by GARY A. RENDSBURG Ithaca, New York The general trend among scholars in recent years has been to treat the genealogies recorded in the Bible with an increased skep- ticism. Whereas past generations of scholars may have been ready to affirm the trustworthiness of at least some of the Israelite lineages, current research in this area has led to the opposite con- clusion. Provided with parallels both from ancient Near Eastern documents and from the sociological and anthropological study of tribal societies of the present, most scholars today contend that the biblical genealogies do not constitute a reliable source for the reconstruction of history.' The current approach is that the genealogies may retain some value for the reconstruction of political ties on a national or tribal level,2 but that in no way should they be taken at face value. This is especially true for those genealogies which purport to be from early Israelite times, such as the lineages of Moses or David. In the present article I will offer some evidence which, depending on how it is judged, may stem the tide described above. The approach to be taken will differ from recent work on the subject, in that it will adduce no external evidence from either ancient or modern times. Instead, I will concentrate on the genealogies them- selves, in particular those lineages of characters who appear in Exodus through Joshua. I anticipate one of the results of my analysis with the following statement: the genealogies themselves 1 See especially R. -

Abraham David 575-646-1866 [email protected]

A Abraham David 575-646-1866 [email protected] Innovative Media Research & Extension - Graphics & Animation Acharya Ram 575-646-2524 [email protected] Agricultural Economics and Agricultural Business Achen Aspen 575-355-2381 [email protected] De Baca County Extension Office Aguirre Adrian 575-646-1173 [email protected] Innovative Media Research & Extension - Multimedia Programming Aguirre Esther 575-646-1173 [email protected] Innovative Media Research & Extension - Faculty Unit Ahmed Arif 575-646-7345 [email protected] Center for Animal Health and Food Safety Ahn InSook 575-646-2424 [email protected] Family and Consumer Sciences/Ext. FCS Akande Raphael 575-243-1386 [email protected] Bernalillo County Extension Office/ACES IT Allen Sam 505-960-7757 [email protected] Agricultural Science Center at Farmington Allison Christopher "Chris" 575-646-5668 [email protected] Tom and Evelyn Linebery Chair Anchang Julus 575-646-5211 [email protected] Plant and Environmental Sciences Anderson Jeff 575-525-6649 [email protected] Dona Ana County Extension Office Anderson John 575-646-5818 [email protected] Jornada Experimental Range Aney Skye 575-646-4842 [email protected] Jornada Experimental Range Angadi Sangu 575-985-2292 [email protected] Agricultural Science Center at Clovis Aragon Mayra I. 505-243-1386 [email protected] Bernalillo County Extension Office Aranda Anthony 575-646-2729 [email protected] Fabian Garcia Research Center Archuleta Franchesca 505-544-4333 [email protected] Torrance County Extension Office Armstrong Kylie 575-374-9361 [email protected] Union County Extension Office Arrellano Ellen C. 505-852-4241 [email protected] Agricultural Science Center at Alcalde Arrigucci Andrea 575-646-5566 [email protected] School of Hotel, Restaurant & Tourism Management Ashcroft Nicholas 575-646-5508 [email protected] Tom & Evelyn Linebery Chair Ashley Ryan 575-646-4135 [email protected] Animal and Range Sciences Atwood Susan Y 575-533-6430 [email protected] Catron County Extension Office Azcarate Jessica 575-646-1889 [email protected] Family and Consumer Sciences/Ext.